FORUM

Web Opera and Opera on the Web

edited by Sofija Perović

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 2, Issue 2 (Fall 2022), pp. 85–136, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2022 Sofija Perović. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss19972.

As an aspiring opera stage director with experience in music and theater, I started my research on opera stage direction more than a decade ago. At that point, I had not fully realized the potential and the importance of the Internet as a tool in contemporary opera productions, and yet all my work was somewhat conditioned and certainly influenced by it. My first experience with opera was, of course, in person. Nevertheless, around the same time I also started watching the VHS tapes of operas lent by my music teachers. I still vividly remember Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s production of Rigoletto and Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Flute. Those VHS tapes were soon replaced by DVDs and followed by live streaming in cinemas, on television, and finally on the Internet. Since I was living in Belgrade, Serbia, it was thanks to those privileges of modern technology that I had the opportunity to keep up to date with what was going on in the opera world.

To me personally, the Internet represents a window to the world. It brought me to La Scala, the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Opera House, the Opéra de Paris, and many other places, but it also gave me access to learning and research, and it allowed me to be in touch with colleagues all over the world, to connect with professionals with whom, otherwise, I would not have had the opportunity to get in touch and work with. Now, I use the Internet in my professional engagements as opera stage director every day—be it to do the research, to connect with collaborators, or as a tool in the process of making a new opera. For all the productions I worked with, most of the marketing and publicity was made over the web, on social media, and online magazines. It was partly a strategic decision, but it also came naturally since everyone involved in the process used social media on a daily basis.

Besides the use of the Internet as a tool of communication and promotion, the most exciting experience I had with it was when I staged Francis Poulenc’s opera La Voix humaine at the Bitef theater in Belgrade in 2016. In this production, I made use of the web camera with a specific aim—I wanted to bring closer the story of Elle to a contemporary audience who could no longer relate to the troubles of the first telephones and interruptions made by party lines. [1] By showing their proper reflection on the stage, I wanted the people in the audience to get involved in the story, but also to raise awareness on the privacy issues related to online communications and the sharing of personal data over the Internet—and that is why I opted for a web camera.

This is just one of many examples of taking advantage of the Internet and its products and services on the operatic stage. As we keep using it more and more in our daily lives, its use is expanding and becoming a standard in opera as well. However, even though its presence is constantly challenged and reexamined, after its COVID-19-related explosion in relevance new tendencies (such as web operas) are now seen in a different light.

The year 2020 has changed the world as we know it. The global pandemic has affected artistic and cultural scenes more than any obstacle over the past century, including wars and socio-economic crises. In a recent article, Anna Schürmer identifies social distancing as “a central (un)word of the pandemic year 2020” [2] and examines the transformations the opera world went through during the COVID crisis by identifying this historical moment as one of the main reasons for the “acceleration of digitisation and the appearance of non-human presences on virtual stages.” [3] The global impact of the pandemic to the (mostly performing) arts scene reminds us of its interrelation with the general health of our planet, giving another tragic topicality to a relatively new operatic genre called “eco-opera.” This worldwide emergency has also highlighted the role of technology not only in our daily lives, but also as an essential part and tool for the performing arts and opera.

This journey began with the first live broadcasts of opera on television and in cinemas, soon followed by online streaming. It was in 2006 that the New York Metropolitan Opera started its successful series of live streamings “Met Live in HD.” Other important venues, such as The National Theatre in London, followed the Met’s example and started providing live streamings of its productions, first in movie theaters all around the world, but soon increasingly online as well.

Even though no one was prepared for such a drastic change in people’s habits and artistic creation, the (not so) recent liaisons that opera entertained with technology and media came as practical, to say the least, during this period. The new subgenres such as web opera, however, came into being long before the coronavirus. Modern technologies were used on operatic stages on a regular basis—e.g., the common use of videos in opera stagings that even resulted in the creation of new software. Some of the most representative examples of such practices can be found already at the end of the twentieth and the first two decades of the twenty-first century, and they include works by composer and innovator Tod Machover, namely his interactive Brain Opera from 1996 which “invites the audience to collaborate live and online,” and the “robotic” opera Death and the Powers from 2010 which tells the story of the inventor Simon Powers conducting his final experiment and trying to project himself into the future. [4] A couple of years earlier, for the revival of his staging of Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust at the Met in 2008, director Robert Lepage and his artistic team “Ex Machina” recreated the video projections using an infrared camera that detects movement to make the projection interactive, which at the time was a novelty in the practice of video art for opera. The interactive images responded to the movements of the performers on stage, but they were also modified by the singers’ voices. The audience had the opportunity to see something close to the experience of hallucinating. The specificity of this type of video projections lies in its sharing the same quality of live performances, as each performance is different.

Experimentations in the field of video art for the opera stage have been replaced by developments in the field of broadcasting and filming. The absence of the audience in theaters opened new possibilities for the filming of the shows. For instance, it was possible to install the cameras directly on stage, which would be problematic during a live performance (except for when cameras on stage are used for specific purposes—e.g., in many productions by Frank Castorf or, amongst others, in the staging of No Exit by Andy Vores at the Florida Grand Opera in 2013). Since its early era, postdramatic theater has always made use of video on stage, highlighting the poetic dimension of a production more than its content, as it can be seen in the works of Jan Fabre, Romeo Castellucci, or Robert Lepage. Castellucci and Lepage have used their experience with technology and media in spoken theater and have transposed it to the opera.

A new operatic genre has recently emerged from this marriage between opera and new technologies and from the desire to make opera more accessible to young audiences—web operas, in fact, broadcast only on the Internet and not in front of a live audience. The question that has emerged since is whether the very essence of opera as a genre has changed in the age of the Internet or is it only our view of opera (and more generally of art) that has been altered?

Operas for television have been around since the 1950s; yet, with new digital technologies the expectations of global audiences have started to change. Audiences, too, have changed. Today, with Internet at the opera becoming everyday reality, who are the spectators who go to the opera house and those who prefer to stay home and watch it as a TV/computer/mobile phone broadcast? Opera stage director Dmitri Tcherniakov sums the issue up: “The opera on video, at the movies, on Youtube? I don’t pay much attention to it, it seems quite natural to me, like mobile phones, computers, and foreign languages.” [5] From a different perspective, Romeo Castellucci finds opera on screen to be “an inherent contradiction” as “one has the impression of what it might look like in reality, but it is not ‘the thing.’ The thing is an encounter, the thing is an act of presence, which is increasingly rare today.” [6] In her book Opera as Hypermedium, Tereza Havelková notices how liveness today “maintains a high degree of cultural prestige.” [7] New generations of opera creators are, however, less interested in keeping that allure of cultural prestige and are aiming more and more to bring opera to wider audiences (be it in more approachable public venues or virtual spaces).

The connection and interdependence between opera and media began already in the nineteenth century with the first broadcasts of opera through telephones. There have even been examples of inventors who thought of opera for their creations. We already know that the tendency and desire to broadcast opera to remote audiences was already in place during the nineteenth century, and that the idea of making opera accessible to a wider audience isn’t a recent phenomenon. Thomas Edison was somewhat prophetic in providing for this, now customary, practice—i.e., watching operas on screen performed by singers who are no longer with us—when he collaborated on the creation of William Dickson’s kinetograph: “I believe that in coming years … grand opera can be given at the Metropolitan Opera House at New York without any material change from the original, and with artists and musicians long since dead.” [8]

Given the abundance of scholarly literature on the phenomenon, with writings appearing already in the 1980s, video and new technologies, as well as new filming techniques, have remained closely linked to opera since then. During this period of the pandemic, the bond between opera and the Internet grew stronger. We have already mentioned the new genre of web opera and the examples dating from the last few years before the COVID-19 pandemic, but during this period without live performance activities, another new genre (or subgenre) has emerged: Zoom operas (i.e., operas created exclusively for being broadcast over online peer-to-peer software platforms for video communications such as, among others, Zoom). It will be interesting to observe the future of this phenomenon, as Zoom is a digital platform which invites users to actively participate (with the likes, the applauses, and other possible“reactions”); this would create an atmosphere quite different from asynchronous performances one can experience on YouTube or Vimeo, for example, where the audience is invisible and have no direct relationship with the artists (of course, people can leave comments, likes, or dislikes, but this is not available to the artists in real time). How will this relationship between new technologies and opera develop in the future remains to be seen.

Yet, the subjects developed in the libretti for web operas are quite diverse and not necessarily focused on contemporary world issues. For example, the first web opera created in France, Ursule 1.1, directed by Benjamin Lazar for the Théâtre de Cornouailles in 2010, recounts the story of Saint Ursula, Princess of Brittany, who allegedly succumbed to the arrows of the Huns on her pilgrimage route to Rome, along with 11000 other virgins. As part of the research initiative “Opera and the Media of the Future—OMF,” the Center for Research in Opera and Music Theater (CROMT) commissioned two “mini operas for the web” to be hosted on their website and presented at a two-day forum held in October 2014. The first of the two winning projects was presented at Glyndebourne as candidates were invited to reimagine opera on the web and ask themselves the following questions: “What does opera ‘mean’ on this scale and through this medium? How can the composer/media artist engage an operatic audience? What is the work’s relation to the ‘live’?” [9] Of the seventeen submitted proposals, the jury nominated two winners: You Are Here (Jaakko Nousiainen, director; Miika Hyytiäinen, composer) and RUR-Rossums Universal Replicants (Martin Rieser, digital, visual, electronic, and interactive artist; Andrew Hugill, composer). The concept of You Are Here is based on the idea of connecting interior spaces of Glyndebourne Opera to exterior spaces of three opera houses in Berlin (Staatsoper, Deutsche Oper, and Komische Oper). You Are Here is organized around six short visual artworks, each containing a QR code that can be activated with a smartphone camera. The codes connect to short opera videos, forming, as described by its makers, “a virtual peephole between Glyndebourne and Berlin.” [10] Nousiainen and Hyytiäinen have previously collaborated on a similar innovative project called Omnivore, originally conceived as an opera “for mobile delivery.” [11] The idea for this project was born in 2007 when the devices weren’t up to the creator’s idea, so it was filmed only a few years later in 2011, and in 2012 it got its online incarnation. This opera is considered to be the first opera written to be distributed as a mobile application and its making took effort and much enthusiasm and creativity from a large group of musicians, technicians, mobile media experts, video makers, and interface designers, among others. The work is also in the “mini format” since it lasts about twenty minutes, and another curiosity and specificity is the fact that there are several variations of the opera, as the system randomly chooses certain parts and the order of presentation. When compared to live performance, always different (even with the same cast) and unrepeatable, this could be considered as a digital match to the “uncertainty” which accompanies every live event.

As explained in the online proposal, the RUR “mini-web opera provides an explosive encounter between new technologies and the long-established tradition of opera.” [12] By asking the audiences to actively participate through social media, “ RUR transforms the way in which operatic works are produced and consumed” by making the online experience intermedial and immersive.

Two years later, in 2016, during the eighteen months when major renovations prevented access to the building, the Opéra Comique in Paris presented The Mystery of the Blue Squirrel, an opera designed exclusively for the Internet, conceived as “a veritable operatic thriller, [which compiles] veiled references to the Opéra Comique and allusions to the trades and places of the theater. There [are] investigations and thrills but in a zany vein accessible to children aged 8 and up.” [13] This opera in seven scenes (Marc-Olivier Dupin, composer; Ivan Grinberg, librettist and stage director) was born out of the need for the artistic direction at the Opéra Comique to find new places to present its productions during the reconstruction of the Salle Favart. The opera’s director for the live broadcast was François Roussillon, already well-known in operatic and dance circles for his recordings, documentaries, and live filming. This full length web opera was advertised to be watched “on the web and with the family.” On the Facebook event “Webopéra à partir de 8 ans” (Web opera for those aged eight and older) it was advertised as: “Take note of the event for the family to attend the live creation.” Another advertising slogan was: “The room will be virtual; it will be accessed free of charge from the comfort of your personal computer at home.” [14] We can see that the Opéra Comique proposed this work as a family event and insisted on the collective and shared experience, to be consumed in the comfort of your sofa, while also insisting on the (clearly attractive) gratuity of the event. The Opéra Comique published the results and figures regarding the number of spectators for the Facebook event: 2,800 unique visitors for the live broadcast, then 4,226 the days after. On the last evening, the platform recorded 7,362 requests. On social networks, the web opera was a success. Live tweeting amounted to 496 tweets by 112 participants, with 362,654 people being reached globally. On Facebook, 45,292 people were reached, with 725 likes. [15] In any case, these numbers reveal the presence of a strong community, albeit virtual. Through likes and comments on social networks, automatic sharing with friends or followers, the Internet community publicized this web opera created and produced by the Opéra Comique. All in all, a good marketing result, especially as the goal was not only the creation of a new work and genre, but also the presentation and promotion of an opera house which had been closed to the audience for a year and a half. The popularity of the Internet was used also for the educational mission that the management of the Opéra Comique had set for themselves.

Fig. 1. Nico Muhly, Two Boys, Metropolitan Opera. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The link and interdependence between opera and the Internet was already noted in the early 2000s. In February 2007, Opera Europa organized a conference in Paris during which the question of how to rekindle the interest of younger generations in opera emerged. The conference (“European Opera Days”) focused on the possibility of using the Internet for opera as a genre, either for its promotion or for the creation of new types. In his opening speech, Jacques Attali spoke of “the web revolution” and its potential for the realm of opera. According to Attali, the Web 2.0 and initiatives like MySpace and YouTube could succeed in transforming spectators into active protagonists. [16] During the conference, the example of the English National Opera (ENO) and its “Inside Out” project was brought up, which aimed to attract young audiences by using the Internet as well as a familiar language. The ENO website offered the opportunity to attend rehearsals in real time and comment on the latest performances on blogs.

Internet as the main subject of an opera was introduced for the first time ten years ago in Nico Muhly’s opera Two Boys (figure 1), jointly commissioned the by Metropolitan Opera House and ENO, and based on a true story from the early 2000s—a tragic tale of two boys who met in one of the early chatrooms and ended their online “friendship” with one stabbing and fatally wounding the other. Although this is a traditional operatic form, the libretto written by Craig Lucas depicts in an almost naturalistic manner the Internet language, practices, and most importantly problems and perils of the Internet realm which are, unfortunately, still very relevant in today’s society. The core topic of the opera is cyberbullying and its consequences, and the same subject also inspires a three-episode web opera composed by Michael Roth on a libretto by Kate Gale, calledThe Web Opera (figure 2). [17] Another similarity with Nico Muhly’s production is the fact that this web opera (or web opera series) is also based on true events. This work in progress (there are five episodes planned in total) aims to raise awareness over cyber abuse through the operatic medium.

The website Operavision.eu is one of the newest and brightest examples of Internet use for bringing opera to its younger audiences, but also for bringing together its creators or students from around the world without forcing them to change location. “OperaVision is an invitation to travel online to discover the diversity of musical theatre from wherever you want, whenever you want… Convinced that opera can be accessible to everyone, OperaVision also believes in its role as a digital stage for emerging artists… OperaVision seeks to celebrate the positive impact and value of opera to society…” [18] With such practices, the Internet community is offered a new space for exchange, learning, and creation, which is essentially a new experience in operatic practice.

Fig. 2. Michael Roth, The Web Opera, still photo from episode 2.

As Michael Earley noticed: “The laptop is the new keyboard, sound maker, orchestra, canvas and film studio—often in the hands of and under the direct musical-authorial-directorial control of a single artist.” [19] Upload, an opera created by Michel van der Aa (composer and multimedia artist) for the 2021 Bregenz Festival (with its film version being screened by medici.tv and streamed by the Dutch National Opera), demonstrates this in the most obvious way. As a talking head reminds the audience during the play, “the human mind is the last analog device in the digital world.” [20] Social dementia combined with the desire to live forever are questioned in this innovative work. Our “analog devices” seem to have insufficient memory to keep alive memories of our ancestors, and Michel van der Aa examines other options we may have. This opera explores the possibility of “uploading” thoughts and memories in order to achieve an eternal digital consciousness after death. Aside from the libretto’s original topic, the opera is innovative in its technical aspects, too. The video projections used on stage are diverse: one screen shows to the audience the practical side and the process of “uploading,” while the other live motion-captured projection represents the digital avatar of the character who “uploaded” his thoughts and memories. Mixed reality was also used by van der Aa in his VR installation Eight. Even though Eight is more of a unique mixture of musical theater, visual art, and virtual reality than strictly opera, nevertheless it deserves to be mentioned here since such experiments putting together operatic style of music with new technologies paved the way for their usage on the opera stages. Today, even the term “opera” is constantly reexamined, sometimes denied, and reappropriated by artists for other purposes.

In 2015, the Opéra national de Paris developed a third, virtual/digital stage in addition to its two existing ones at the Palais Garnier and the Opéra Bastille. This free platform, called 3e Scène, was launched with the idea of attracting new audiences, especially young people, and getting them interested in opera and ballet.

Internet is a public place, a collective meeting place, a place for expression and creation. … In this new space, the Paris Opera intends to continue its dialogue with the public and also to make new friends. 3e Scène opens wide its doors to visual artists, filmmakers, composers, photographers, choreographers, writers, and invites them to come and create original works relating to the Paris Opera. The relationship between the Opera and the works created may be forthright, robust, subliminal, drawn-out, extended or even distended. But above all we want the artists to make the Opera their own, to draw on its resources, roam within its walls and meet its talents in order to reveal places, colours, history, questions and people through creation. This 3e Scène has neither equal nor model. Open to the world, it invents a space where tradition, creation and new technology unite as symbols of modernity.[21]

Although the works presented were not full operas and could not be defined as web operas, 3e Scène represented a new interpretation of opera on the Internet. In 2017, 3e Scène organized its first festival at the Gaîté Lyrique, [22] and for the 2019–2020 season the famous French YouTuber Jhon Rachid was invited to perform on the digital platform Yet, not every story has a happy ending: as of 2022, the website for 3e Scène has vanished from the Opéra de Paris online presence and has since been replaced by a far more traditional pay-on-demand platform called “L’Opéra chez soi.”

The interest in attracting new audiences to opera (and who hopefully will keep coming back to it), and the desire to find and create new forms within the operatic genre have given rise to many novelties by changing our perception of opera and by making it closer to modern, “digital” sensibilities. Perhaps one of the greatest achievements in connecting the Internet and opera has been the foundation of web opera as a new genre with a great potential, even though it remains to be seen which direction it will take and how it will evolve. Time will show whether the creation of web operas was simply a marketing strategy to attract new audiences or whether it will give birth to artworks that will change the operatic genre and its stakes for generations to come.

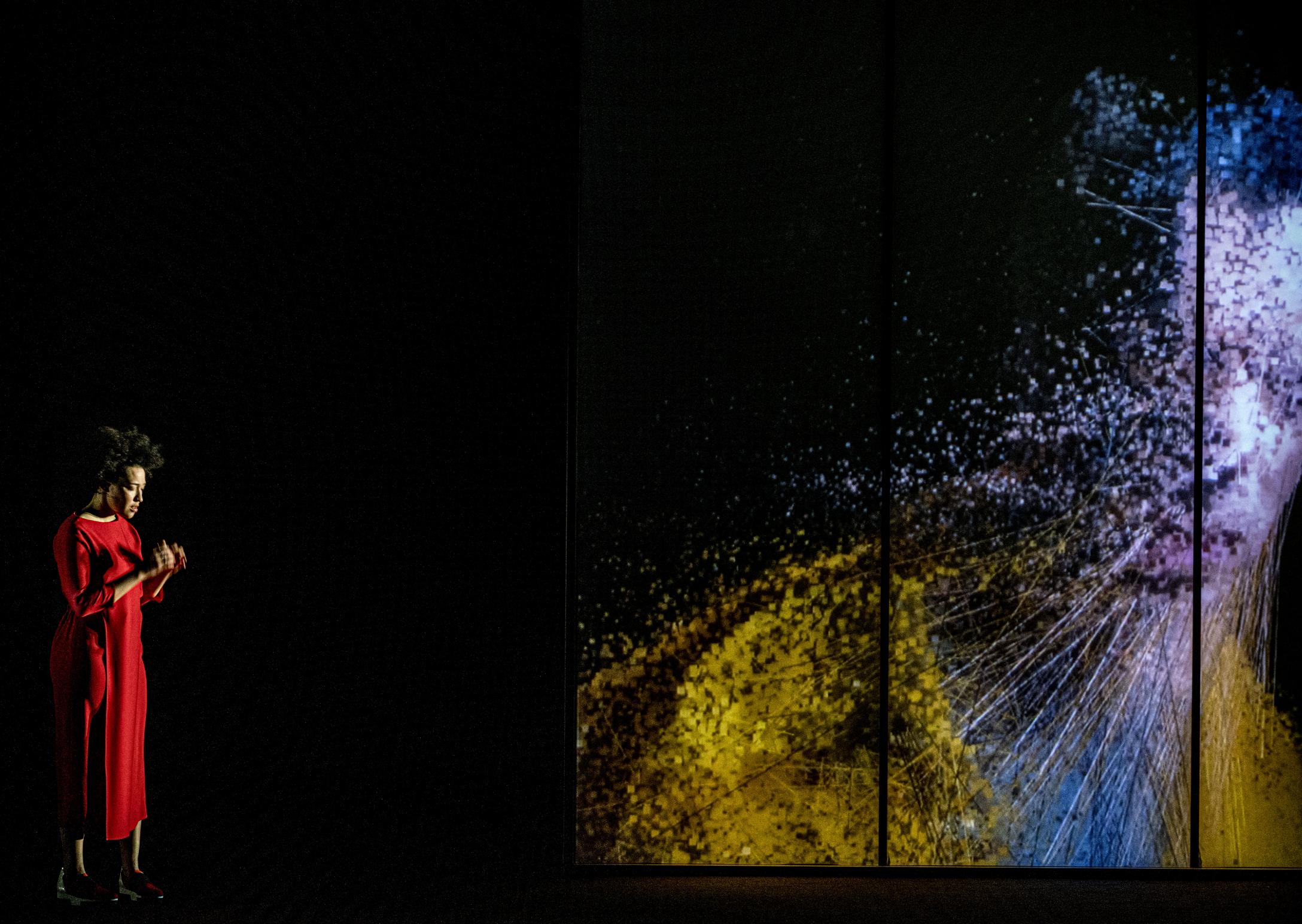

As Vlado Kotnik affirms, “the production of opera has never been about performing a musical work on stage only, but also about performing a highly contested social arena.” [23] The social arena has drastically changed during the last decade, especially during and after the pandemic, and has been mostly transferred to the realm of social media. How did this shift influence the operatic world? What are the advantages and disadvantages of social media? and, Can they be treated as tools on the operatic stage? I talked about this and many other topics with American soprano Julia Bullock, whose voice is being heard and spread actively on social media; with one of the greatest stage directors of our time Romeo Castellucci, whose views on Internet and the relocation of live shows to the digital screen are much less optimistic or positive; and with the French dramaturg Simon Hatab, who collaborated to the very special production of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opéra-ballet Les Indes galantes directed by Clément Cogitore at the Opéra de Paris in 2019.

Creating Opera for the Web: Au web ce soir – Ursule 1.1 and Actéon

Caroline Mounier-Vehier *

“Half play, half musical performance,” [24] “cyber-theater,” [25] “cyber-show for web-spectators,” [26] “webcam show … mini-opera,” [27] or simply “opera for the Internet.” [28] The expressions used by journalists to describe Au web ce soir – Ursule 1.1, a show conceived and staged by Benjamin Lazar in collaboration with composer Morgan Jourdain and musical director Geoffroy Jourdain, are varied. The stage director speaks of “live theater on the Internet” [29] and evokes “a new theatrical object, which will be a kind of small opera.” [30] Performed only once on April 29, 2010, at 9pm live on the website of the Théâtre de Cornouaille (www.theatre-cornouaille.fr), Ursule 1.1 was an early example of a performance created for an online audience. Ten years later, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Lazar and Jourdain joined forces with director Corentin Leconte for a new video project, at the crossroads of theater, music, and cinema: Charpentier’s Actéon , this time more soberly described as a “film in sequence shot,” [31] “film,” [32] or “filmopera.” [33] Filmed on December 6, 2020, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, the film was broadcasted on Arte.tv from the 16th of February, 2021.

As film-spectacles, conceived for online broadcasting, rather than filmed spectacles, Ursule 1.1 and Actéon possess several common points which tend to make them similar and at the same time invite to try to define a new spectacular genre of which they would be the first examples. Their respective characteristics will be studied here in this sense. In a broader sense, both these works demonstrate Benjamin Lazar’s reflections on the reciprocal relations and influences between stage and video mediums. Whether it be performances that include video art, recordings of performances, filmed shows, or video shows such as Ursule 1.1. and Actéon, the stage director questions the possible interactions between film and live performance. He explores, with his collaborators, the capacity of video to appropriate the intensity of the stage and its relationship to the present. [34] It will thus also be a question of asking to what extent these two performances studied are representative of this approach and can contribute to a redefinition of the contemporary scene by means of the media available on Internet.

In 2010, for his arrival as associate artist at the Théâtre de Cornouaille, Lazar proposed a show conceived for the web: Ursule 1.1, performed live on the Internet by a soprano, Claire Lefilliâtre, a bass-baritone, Lisandro Abadie, a pianist, Aurélien Richard, and a women’s choir, mixing professional choristers from the Opus 104 choir, and amateur choristers from the Pôle Voix choir of the Maison pour tous Ergué-Armel. We meet Ursula, a young Breton woman of our time, who takes advantage of the communication space offered by the Internet to tell us her story. Dismayed by the mockery of her name, Ursula takes refuge in a library, where she discovers by chance the story of another Ursula, more precisely Saint Ursula, in the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine. This is the beginning of the show as a mise en abyme, the story of Saint Ursula: the departure from Cornouailles and the pilgrimage to Rome, in company of eleven thousand virgins, the confrontation with the Huns on the way back, the refusal to renounce the Catholic faith, and the death as a martyr. Ursula’s project is to gather around her as many young girls as her patron saint: the Internet could thus become the equivalent of Saint Ursula’s cloak, a magical garment under which her companions could shelter and protect themselves. Three narratives are thus interwoven: first, a presentation of Ursula the narrator and of her own project; then, the story of Ursula the character (as told by Ursula the narrator); finally, the story of Saint Ursula (recounted, or dreamt of, by Ursula the character). The three stories together conclude at the end of the show: while Saint Ursula falls under the arrows of the king of the Huns, Ursula (character, but also narrator) herself faints and technicians appear in the camera field to help her. After a blackout, Ursula (narrator), alone on stage, gets up and walks towards the camera to introduce the credits.

At the beginning of the video of Ursule 1.1, five slides follow one another to introduce the show and present the rules of a game that the director and his team have adopted. These rules contribute in defining the characteristics of the new spectacular object proposed: they indicate the chosen media, its specifications, and the constraints imposed to adapt to it. Broadcasted only on the Internet and filmed with a fixed camera, the performance takes the form of an amateur video filmed by Ursula with her webcam. The form coincides with the content, it corresponds to the announced situation: Ursula is an Internet user addressing other Internet users. The choice of the fixed camera is also thought to be in reference to the films by Georges Méliès and to the early days of cinema, as Benjamin Lazar points out: “The difference with another online performance, such as may be practiced for opera or theater, is that the stage frame will also be the camera frame, according to a device that may evoke Méliès’s camera, namely a fixed frame without zoom, posed as a spectator’s eye.” [35]

The camera frame functions as a stage frame. The point of view is not constructed thanks to the movement of the camera around the filmed object, but rather it is necessary to bring in or out of the camera field what should or should not be filmed. Entering the camera field becomes the equivalent of entering the stage, while the off-screen becomes the equivalent of the backstage. The camera itself occupies a place as static as that of a spectator sitting in a theater. For the director, this characteristic makes it possible to distinguish Ursule 1.1 from other forms of online performances. Indeed, in the case of a re-run on the Internet, on television, or at a movie theater of a show conceived for and represented in an opera house, the spectators are offered the broadcast of a show performed in another place, in the presence of other spectators. Even if these initiatives tend to give them the impression that they are attending the performance, they are only external witnesses. What they see is not the performance itself, but a trace of the performance, which also carries a point of view—that which is imposed by the camera. In the case of Ursule 1.1, the performance is available exclusively online. All the spectators of Ursule 1.1 see and hear the same thing, at the same time, no matter where they are.

Moreover, the choice of a fixed camera offers a point of view which corresponds to the so-called “eye of the prince,” the place in a typical Italian opera house from which the optical effect of the decor in perspective is best appreciated. The modernity of the use of the Internet is thus part of a tradition—i.e., that of the characteristic conception of the stage as a “tableau.” [36] As with Italian theaters before the introduction of darkening the auditorium, [37] the question of the attention of the spectators nevertheless arises—another constraint associated with performances on Internet is indeed the ease by which spectators can be distracted, or even abandon the proposed experience. It contributes in justifying the choice of a short format (forty-eight minutes)—i.e., between “the web format” (videos of a few minutes) and “the theater format” (performances of about an hour and a half to two hours), in order to be “in a good in-between time to invite an Internet user to follow the proposal from one end to the other,” explains Lazar. [38] But the work must also be interesting, even fascinating, as the show humorously suggests during a hypnosis scene: Ursula presents the camera with a spiral printed in black on a white wheel, which rotates while she waves her hands in the direction of the spectators, in order to hypnotize them and keep them on the web at her side, as she introduces the story of Saint Ursula. Music can be an asset in this process. Thus, the composer Morgan Jourdain wished to contribute, with the music, to awaken and keep the attention of the audience: “It is necessary to find … in my music … something which allows the spectator, the listener, to capture the attention, so we will be closer to a music one could say charming, charmer.” [39] We find here a founding principle of opera: the enchantment of music is associated with the wonder of images. Jourdain adds: “We will try to use the singing in its simplest relationship, in its Orpheus way, … to tell a story and attract the spectators and the spectator’s attention during the time of the performance.” [40] This reference to Orpheus is interesting for two reasons. On the one hand, Orpheus is a poet capable, through his musical talent, of obtaining from the God of the Underworld the resurrection of his beloved Eurydice. On the other hand, he is an emblematic character for opera since the beginning of the genre, at the dawn of the seventeenth century. This reference thus contributes to the inscription of web opera into the tradition of Western opera. However, in the case of an Internet performance, the music must enchant through the mediation of the screen and despite the physical absence of the performers. Jourdain has therefore composed a music that mixes elements of scholarly and popular music, with particular tunes reminiscent of nursery rhymes, which are at the same time catchy, playful, and easy to memorize. The music creates a link with the spectators, beyond the screen.

Like Ursule 1.1, Actéon is a short opera, lasting about forty minutes, with solo and choral parts performed by the singers of Les Cris de Paris, directed by Geoffroy Jourdain. The notable difference is that this is not a contemporary creation composed for the project, but rather an old work: a pastoral by Marc-Antoine Charpentier which premiered in 1684. The story is inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses: the hunter Actaeon sees Diana bathing with her nymphs, but the goddess discovers him and, irritated, turns him into a stag, so that her own dogs chase and kill him. For this new filmed work, the rules of the game are no longer the same as for Ursule 1.1. This time, the film is not broadcast live, but deferred after post-production work. However, the director did not give up the idea of finding, within the framework of the shooting, a form of urgency specific to live performance. After several work sessions hosted by different festivals, a few days of rehearsals took place at the Théâtre du Châtelet, where the film was shot in one day. Another complementary process is the use of the sequence shot. The film is in fact composed of two long sequence shots, between which the passage is constituted by Actaeon’s gaze: the camera embodies a gaze—form and content, once again, coincide. The sequence shot consists of a single shot covering several locations in the same place, in this case the Théâtre du Châtelet. It implies a precise preparation and a strong concentration on behalf of the performers; any error can lead to having to start the whole shot again. Indeed, if it is possible to work on sound in post-production, the images will not be able to give rise to the same editing work as a scene filmed in several sequences. Filming in sequence thus makes it possible to create a tension that reminds the performers of a public, live performance.

Fig. 3. Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Actéon, directed by Benjamin Lazar, still photo. © Camera Lucida productions.

One of the challenges of the work carried out on both Ursule 1.1 and Actéon is to rediscover certain characteristics of the live performance through the filmed object; in particular, a relationship to the present that gives the interpretation a different intensity from that of a film shoot. It is not a question of trying to reproduce through film a situation and effects identical to those of a theatrical or operatic performance, but of taking into account the specificities of each mode of representation, whether staged or cinematographic, in order to propose a work of transposition—what Benjamin Lazar calls “transpos[ing] the necessity of the present, which is specific to live performance.” [41] The stage director and his team thought about how to arouse a different quality of emotion in the performers than in the movies, one that could evoke that of the stage performance and touch, even surprise, the audience. The shooting conditions are particularly important from this point of view. Shooting live or in conditions close to live due to time constraints or technical challenges, favors awareness of the present and intense concentration, as the director explains:

The technical challenge of the sequence shot is also close to the live performance: it is now or never, as much for the performers as for the technicians. The balance is perilous, the concentration must be at its highest. It’s a challenge that federates a great deal of common energy.[42]

The goal is to put together working conditions that allow performers to bring out a kind of energy close to the one implicit in a stage performance.

However, in contrast to a live performance, the film-spectacle does not bring practitioners and spectators to the same place at the same time. Even in the case of a live broadcast, as with Ursule 1.1, the latter are brought together by being online and sharing the same experience which may or may not be simultaneous, but which allows them to be together virtually. There is therefore no more interaction between them during the performance than in the case of a digital rerun. Paradoxically, the same digital screen that should bring artists and audiences together creates a medial screen and, in so doing, separates them. The question of the relationship between practitioners and spectators is crucial to understand the experience of those who perform and those who attend the performance. In fact, in order to find conditions of play close to that of a live performance, Lazar has reflected on how to integrate spectators. For Ursule 1.1, different possibilities were considered before the performance to find, through the Internet, a substitute for physical interaction, whether it was a button to applaud by “accumulating claps,” [43] a forum-like platform for written comments, or an online chat. As none of these possibilities could replace the presence of spectators in the theater, a compromise solution was chosen, with a few spectators physically present in the theater, on the shooting site.

Fig. 4. Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Actéon, directed by Benjamin Lazar, still photo. © Camera Lucida productions.

But if performers benefit from the gaze and presence of spectators, only a few of the latter are allowed near the stage. Certainly, the digital broadcast, live or deferred, allows to reach a number of spectators much more significant than the number possible during a live performance. For example, the Théâtre de Cornouaille, where Ursule 1.1 was filmed, can accommodate 697 spectators in its main auditorium and 145 in the Atelier. With 5,773 live spectators, Ursule 1.1 has gathered in one go the equivalent of more than eight performances at full capacity. Such an approach also allows for a wider distribution of the show, which can be accessed worldwide, regardless of location (as long as its inhabitants have Internet access) and sanitary restrictions, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, for most of the attendees, the distance imposed by the screen is irreducible. Interpretation undoubtedly benefits from the presence of the audience closer to the performers, but audiences who discover the performance on a screen have a very different experience from that of a live performance. Their absence from the auditorium does not only result in their physical separation from the practitioners—their place within a community of spectators becomes virtual, too. Attending a performance is a social activity and the interaction specific to the performance includes the interaction between different spectators of the same performance. Is knowing or assuming that other spectators are attending the same performance at the same time, but in other places, enough to give the feeling of being part of a community of spectators? Does it allow for the sharing that is part of the common experience that a live performance represents? In other words, is attending a performance on a screen, via Internet, still a collective experience?

Here again, suggestions were made for Ursule 1.1—e.g., the possibility of sitting together in the foyer of the theater or recreating a small community of spectators at home by inviting friends and relatives. [44] An alternative solution was proposed for Actéon, shot and broadcast during a period of restricted contacts and many cancelled performances due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Like Ursule 1.1, Actéon was shot in a theater. However, the theater, in this case the Théâtre du Châtelet, was featured in the film itself, and a member of the audience in the theater was played by the actress Judith Chemla. The mise en abyme of the filmed performance favors identification in those attending remotely, who are invited to recognize the elements of an opera performance in the object offered to them. We also find in the two films the technique of direct address to the camera, but in two different ways: whereas Ursula (narrator, then character) addresses the viewers to invite them to discover her story, like an Internet user calling out other Internet users within the same community, the spectator embodied by Judith Chemla initially addresses Actaeon himself. The film viewers are thus invited to a particular empathy towards a character to whom they can relate by the look. At the same time, they can recognize themselves in the character of the spectator, who is a figure of spectator within the work itself: her listening, her attention, her reactions are all clues that guide the listening, the attention, and the reactions of the audience behind the screen. Failing to recreate through the screen a community and, more broadly, an encounter in the present between artists and spectators, the film plays with the codes of live performance to accompany the audience in its discovery of the work and invite it to join the (virtual) space of the performance.

Despite their numerous points in common, Ursule 1.1 and Actéon do not correspond to one and the same proposition of a new genre, be it web opera or filmopera. Their peculiar modes of transmission—the first live, the second pre-recorded—change the conditions of reception and thus contribute to their differentiation. They are also different from other proposals that have emerged in recent years, such as Le Mystère de l’écureuil bleu, a comic opera by Marc-Olivier Dupin and Ivan Grinberg created for the web in 2016 at the initiative of the Opéra Comique, which was at the time under renovation. Albeit initially conceived as a “web-opéra,” Le Mystère de l’écureuil bleu was eventually staged at the Salle Favart in February 2018.[45] Ursule 1.1 and Actéon, on the other hand, are not meant to be performed on stage. These two film-spectacles remain hybrid objects, experiments that use the Internet to think differently about the relationship between video and live performance. Without denying the fundamental difference between a work created and presented at a distance, on a screen, and a performance that implies a simultaneous presence of the performers and the audience, these works nevertheless attempt to transpose into film a relationship with the present that only a stage performance allows. In doing so, they invite us to rethink video art practices and perhaps even to renew them.

(translated by Sofija Perović)

“Transposing the Necessity of the Present.”

An interview with Benjamin Lazar, conducted by Caroline Mounier-Vehier on September 23, 2022.

After discovering baroque declamation and gestures with Eugène Green, in addition to training at the École Claude Mathieu, French actor and director Benjamin Lazar became known to the public with the resounding success of his staging of Le Bourgeois gentilhomme by Molière and Jean-Baptiste Lully (which has been on tour from 2004 to 2012). A sought-after performer for the baroque stage, he is also interested in a variety of repertoires, from Stefano Landi to Karlheinz Stockhausen, and has collaborated to a variety of contemporary creations (Oscar Strasnoy’s Cachafaz, 2010; Ma Mère musicienne with Vincent Manac’h in 2012, among others). In 2010, he joined forces with composer Morgan Jourdain and conductor Geoffroy Jourdain for an original production: Au web ce soir – Ursule 1.1, a web opera filmed and broadcast live from the Théâtre de Cornouaille. Ten years later, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Lazar and Jourdain planned another show for the web: Charpentier’s Actéon, a film-opera recorded on December 6, 2020, at the Théâtre du Châtelet and broadcast on Arte Concert in 2021 (see the previous section of this Forum).The interview presented here is based on this new spectacular object to reflect more broadly on the relationship between video and live performance in the work of Benjamin Lazar.

Caroline Mounier-Vehier: For several years now, you have been working with video: video recordings or films of shows, but also videos that become material for the stage work or even videos that are themselves performances. What is the difference between preparing a recording of a performance, the transmission of a work, and conceiving a video that is the work itself?

Benjamin Lazar: The filming of Le Bourgeois gentilhomme was directed by Martin Fraudreau, [46] who also made a beautiful “behind the scenes” documentary. [47] I then began a collaboration over several years with Corentin Leconte for Pantagruel, [48] Pelléas et Mélisande, [49] Phaëton, [50] among others. The progress of the cameras and the care of the director Sylvain Séchet allowed us to capture L’Autre Monde ou Les États et Empires de la Lune, [51] a show entirely by candlelight, without any electrical reinforcement. We wanted to go further and make the recording of a second work. We had the time and the means for Traviata – Vous méritez un avenir meilleur. [52] The show premiered at the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in 2016. We wanted to impart the feeling of intimacy offered by the configuration of the Bouffes du Nord: the absence of the orchestra seats allows the actors to come forward and enter the great cauldron of the hall, to be with the spectators. In this intimacy, the spectators create their own film, they are their own camera, they choose details, move from one to another and write their own show. In order to create this feeling of intimacy in the film, Corentin Leconte felt that it was necessary to transpose it and impart a personal gesture on the work. In this case, we chose a completely scripted sequence shot, with a few technical interruptions, while leaving the possibility for chance to create happy additions to the shot. This onboard camera also allowed us to give a documentary quality to the images, reinforcing the impression of recounting the story of La Traviata as well as the relationship that the singers and instrumentalists have with the music.

We organized a performance with invited spectators who knew they were going to attend a shooting. Their presence was important because it contributed to the energy of a performance. We were thus in a kind of in-between world between the shooting and the performance, with a very particular atmosphere, which also creates a particular emotion. I think that the presence of the public contributed to the emotion that we feel in the actors to which the film testifies. We then completed the film with more traditional shots, again during a public performance. The cameras were unified, creating a slight instability on the fixed cameras that can be typical of a documentary in situ. This effect of reality also seemed interesting to us in relation to the history of this opera, which is the first to have been inspired by a recent news item, for six years separate the death of Marie Duplessis from Verdi’s opera.

CMV: In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of many shows. It was at this time that you directed the film Actéon , which had the peculiarity of not being a classic recording, but rather a video object in its own right, this time dissociated from any public performance. Was the process similar to imagining a film for a show based on a live performance project?

BL: A creation is always the result of a desire and circumstances. This time, the proposal came from Geoffroy Jourdain, who directs the ensemble Les Cris de Paris. Geoffroy was the musical director of Au web ce soir – Ursule 1.1, [53] the first video object created for the Internet that I had proposed when I first arrived as associate artist at the Théâtre de Cornouailles. We were eager to do it again for a long time, but it’s not easy to find the finance for this type of project that doesn’t fit into any box. In 2020, when all the theaters were closed because of the pandemic, Jean-Stéphane Michaud, producer at Camera Lucida Productions, received many requests for filming. He was looking for a different format and Geoffroy Jourdain told him about our desire to do a live filmed work again. We proposed to replace the cancelled performances of Les Cris de Paris with a film project associated with the Théâtre du Châtelet. We were able to work in different places, each time proposing a session open to the public, which allowed us to arrive with many working hypotheses at the Châtelet, where we rehearsed for a few days before filming the sequence shot in one day.

CMV: In 2010, Ursule 1.1 was an original work, with music composed by Morgan Jourdain. In 2020, you filmed an old play: Actéon , [54] a pastoral by Marc-Antoine Charpentier created in 1684. Why this choice?

BL: It is a work that suited Les Cris de Paris very well, with both magnificent choral parts and the possibility for the choristers to become soloists at certain moments. It is also a short work, whose form corresponds well to the sequence shot since everything happens without interruption, from the arrival of the troop of hunters in the forest to the death of Actaeon. We have the impression of following a cinematic sequence with simultaneous events: the hunters who leave with Actaeon on one side, Diana at the bath on the other side, and then the two spaces that come together with the meeting between Diana and Actaeon. It was therefore ideal for this type of shooting. The project evolved again afterwards. While for Ursule 1.1 we had given a live online meeting, for Actéon we shot in sequence and did a post-production work before the broadcast on Arte.

In both cases, it is not a question of an adapted stage project, but of an object designed specifically for the camera. For Actéon, Adeline Caron conceived a scenography that was not made to be seen by an audience, but to be filmed by the camera, which gave us the possibility to work in a more metonymic way. For example, the scene of the nymphs bathing with Diana is represented with three aquariums in which the singers plunge their hands. With Sylvain Séchet’s lights, the crane camera coming closer to the faces filmed behind the aquarium, the spectator is in the water, a process that joins the way the imagination works in the theater. It’s a place where you can make people dream with little: aquariums, a painting that travels, things that we don’t allow ourselves as much in the cinema where there is often a demand for reality.

CMV: Even if your Actéon is conceived as a video object, certain elements of your staging remind us that it is a work written for the stage, such as the presence of a spectator played by Judith Chemla.

BL: During the open rehearsals, we realized that telling the story of this metamorphosis the first time would relieve the audience of the effort of recalling a myth that they would only vaguely know. The difficulty of seventeenth-century language and the spread of the story required a concentration that could have weakened the emotions. What is interesting is to see how the composer revisits a common place, but for that to happen, the place must first be common. In open rehearsals, I told the story beforehand. For the film, I wanted to write a prologue and we added a spectator, but a very involved spectator since she addresses the camera as if the spectator were Actaeon.

The prologue has a preparatory narrative function and establishes a certain relationship with the camera from the beginning of the film. The idea is to create an equivalence between the hunter Actaeon, condemned to death for what he has seen, and the camera, also a hunter of images, showing that there can be a danger in wanting to look, both for Actaeon and for the viewer. I also wanted the film to end as it had begun, with a camera perspective. We can thus say that the spectator, played by Judith Chemla, has forcefully projected herself into the story, so much so that she has metamorphosed herself into a new Diana.

CMV: The character of the spectator is even more interesting because she has a relay function for the spectators who watch the film: she accompanies them in the work and thus allows to reduce the distance that the screen implies.

BL: That is why this address was important. Judith Chemla has such grace and emotional involvement that her character goes beyond the mere convention of the story. This is also what allows us to transpose the necessity of the present, which is specific to live performance.

CMV: As in Traviata – Vous méritez un avenir meilleur , would one of the important aspects of the film for you to be to find a form of intensity proper to the scenic, public representation?

BL: The situation is not exactly that of a public performance, but it is not only a shooting either, due to the presence of an audience or a single spectator. The technical challenge of the sequence shot is also close to the live performance: it is now or never, as much for the performers as for the technicians. The balance is perilous, the concentration must be at its highest. It’s a challenge that federates a great deal of common energy.

CMV: To what extent are Ursule 1.1 and Actéon related?

BL: Ursule 1.1 is a bit like Actéon’s big sister. It is almost the same object, but with different productions. We drew a certain number of ideas from Ursule 1.1, which was already a work combining music and theater. We also find the same need for concentration. The big difference is that for Ursule 1.1 we chose a fixed camera, like Georges Méliès’s. The camera does not move, it is the objects that move relative to it, with rolling sets, scale effects, objects of different sizes. For example, to represent a sea voyage, a small boat was placed in the foreground, in front of the camera, and the actors in the background on rolling platforms pulled by technicians. For Actéon, on the other hand, we used two types of cameras. The first was an on-board camera with an operator who first followed the spectator, then became the eye of Actaeon, and then followed Actaeon transformed into a stag as he made his way around the stage of the Théâtre du Châtelet. The second camera was a telescopic crane operated by three technicians. It was like a Bunraku puppet, with the main cameraman, who focuses, and two assistants.

At the moment, the term “in-between world” is dear to me because it is the title of a project I am working on—these films are proposals that float between several genres, between several worlds. It is always interesting when a work is not completely assignable to one genre or another.

CMV: Have these experiences with video changed your stage work and more generally your relationship to the stage?

BL: It’s quite different to think for the camera or for the stage. The image filmed on stage should not be a validation of reality. When it intervenes in a performance, it must be necessary. For Phaéton by Lully, for example, I worked with Yann Chapotel. We wanted to tell the power of the show and the show of power in Phaéton thanks to the video. To show how Phaeton’s race and the great chaconne of Act III testify to the characters’ desire to make a spectacle of their power, Yann produced a sequence of military parades that he set to the rhythm of Lully’s chaconne in such a way as to gradually create an abstract kaleidoscope. At the end of the show, Phaeton’s race was also associated with filmed images, but with reading keys: Phaeton was compared to a pyromaniac child, who plays with matches.

Usually, when I feel the need, I introduce filmed images or video art into my shows, always remaining attentive to the ways in which the technology is used: what interests me is to find a form and a content that make this use necessary, so that it does not extinguish the subject. Perhaps the fact that I have shot recordings or filmed objects such as Ursule 1.1 and Actéon makes me want to continue the experience. I have worked on several occasions with the filmmaker Joseph Paris, a true poet of the image and of editing, who manages to create an extremely strong dreamlike impression in his films. These images have a life of their own, you feel their materiality and their presence assert themselves at the same time as the things filmed—exactly as actors are, in the same presence, themselves and the character. We recently created a new show, La Chambre de Maldoror, at the Théâtre des 13 vents in Montpellier.[55]

CMV: When you stage filmed objects, a director accompanies you. Do you plan to make films yourself or is it the work in pairs that interests you the most?

BL: Everything is open. I like collaborations, but maybe at some point I’ll move on to co-directing or directing. When I work with directors, they make a lot of suggestions. We talk about shot values and intentions, we look at the cut together, but they have a fundamental creative part because they know the necessities and the placement of the cameras, technical aspects for which I have intuitions but do not control. In the creative process of Actéon, another important stakeholder was the draughtsman Benoît Guillaume, who made sketches and helped make a storyboard from photos that I took to prepare the shots.

I am interested in cinema, but more recently I wanted to share with the public the particular concentration that filming creates and the reflections that filmed projects engender. In my project L’Entremonde – including the associated workshops conducted with, among others, the composer Pedro Garcia-Velasquez and the directors and actresses Jessica Dalle and Alix Mercier [56] – I experiment with a public of all ages and backgrounds a creative process based on a three-dimensional recording technique, binaural recording. This allows me to explore the notions of image and inner cinema, through the accumulation and solicitation of images in contact with other images, of works of art. If I say the word forest to you, for example, you will search your memory for a certain number of images with which to compose a chimerical forest. In the workshop, we share what this word evokes in us: for some it will be the smell of wet leaves in autumn, others will have more sonic references, others still will think of light. Soliciting inner images is universal, but each person does it in a different way according to his or her background. Today there are new tools to produce fiction and images, but it is crucial to maintain our ability to create and share inner images. This is even more important at a time when, with the development of the so-called metaverse, they would like to make us to believe that we are only waiting to escape into ready-made inner films, a ready-made clothing for imagination. It is not a question of rejecting these technologies in a backward-looking way, but of being attentive to protect our inner images in front of what looks like an attempt at annexation.

What we put into shape in the workshops is in line with what I think in general of the image in theater—a thought that I share, I believe, with set designer Adeline Caron, with whom I have been working for twenty years: the image must always contain enough gaps and absences to arouse a desire for completeness in the spectators, so that they can project their memories and desires onto it. There are quite concrete procedures to achieve this, formal and structural answers that are diverse and always to be sought, to be renewed. There is no single recipe. For a long time, I used darkness to leave space in the image—and I still use it, because we imagine what we don’t see. But I also know that sometimes a full fire can be full of mystery.

Caroline Mounier-Vehier received her Ph.D. in Theatre Studies from the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 in 2020. Since her dissertation, entitled La scène lyrique baroque au xxie siècle: pratiques d'atelier et (re)création contemporaine [Baroque Musical Theatre in the 21st Century: Workshop Practices and Contemporary (Re)creation], she has been studying the conditions of production, interpretation, and reception of early music performances on the contemporary stage. She has published several papers and given numerous talks on the subject. Caroline is also active as an orchestra manager and concert organizer.

Romeo Castellucci in conversation with Sofija Perović [57]

Romeo Castellucci is an Italian stage director, a lighting and costume designer, and a visual artist known all over the world for his theatrical language based on the totality of the arts. Besides being one of the most sought after and esteemed directors of our time, Castellucci is also a published author of more than dozen books and theoretical essays on stage directing. Castellucci’s work is characterized by strong images created of the primacy traditionally afforded to the dramaturgy and the text, exploring instead other means of stage expression such as music, painting, architecture, among others. He is regularly invited to work in the most prestigious international theaters, opera houses, and festivals on all the continents.

Sofija Perović: At the heart of your productions, regardless of genre or venue, whether it is opera or spoken theater, baroque, romantic or contemporary music, we can always recognize the human being, its condition, humanity, and humanness. From your point of view, as an artist who actively questions the human condition in his works, what role do you see for the Internet in its future? Is the Internet a tool which could contribute to cutting back alienation among people, or is it putting in danger the very essence of human beings by changing and challenging the codes of communication?

Romeo Castellucci: I’m not so confident in such a way of communicating because I think that mostly it is a matter of social control, and not only social control, but much more. In my opinion, it is the control that goes into the intimacy of people. I have to say that it is useless to fight against the Internet. It exists, but I try to keep myself apart from this kind of illness, because the Internet is a way to communicate with other people through an architecture built by somebody else. The idea of Internet communication is such that communication is under control in the architecture. We have the impression of being free, but it is a cage, and we like this cage. In my opinion, it is a form of slavery—a soft slavery, an invisible slavery, but still a slavery. Especially since it concerns the intimacy of each of us. There is a metaphysical side in communication. On the other hand, art should be a switch of this forced communication. We are obliged to communicate in this architecture, and I believe that art is first of all an experience. In my opinion, art should be an experience, and in the communication which passes through the Internet there is no experience. We only exchange the same words. The word on the Internet is a circular word that has nothing to do with me, it is totally detached from experience. However, I am not the right person to talk about that, as it would be more suitable for a sociologist—and I am not a sociologist, I am not a professor, nor a specialist of these things. On the other hand, I fight communication. Art is a fight against communication, in my opinion—it is always personal. On a stage there is nothing to communicate; it is rather a revelation that we receive on a stage, a revelation that is also outside language and that is also why our body, the body of the spectator, is present. Without me (spectator), the show does not exist, because it comes from me, I am half of what I’m seeing. It is an encounter. Theater is the art of contact, it is based on the reciprocal presence between what happens on stage and me sitting in the theater, of my body meeting another unknown body. Obviously the Internet is not like that, it is a fiction that is atrocious. I don’t want to be the enemy of the Internet; if it exists, it means that there are reasons for its existence. I don’t want to make a criticism of the Internet as such, but as a way of communicating it is disturbing.

SP: How do you feel about the online broadcasting of your work? And what future do you predict for newly emerged genres such as web opera or Zoom opera?

RC: No, that doesn’t make any sense. Sometimes I do the work at the opera and there is a video documentary that is programmed by channels like Arte, for example, but that’s not theater, it’s a documentary, so to say. It’s a totally distant experience. One has the impression of what it might look like in reality, but it is not the thing. The thing is an encounter, the thing is an act of presence, which is increasingly rare today. I can accept it as a documentary, but that’s not what theater is. During the pandemic, we did theater broadcasts, but it’s a stupidity, it’s an inherent contradiction. When we enter a theater, we are in danger. When we watch something at home, we are protected and that prevents the theater experience, in my opinion. It’s just my opinion.

SP: We’ve already had the opportunity to see the use of artificial intelligence in opera, the posthuman condition of the likes of avatars replacing singers or dancers. How do you feel about that? Is it something we might expect to see in your future work?

RC: In my opinion, if there is no original idea behind the use of new technologies, it is nothing more than a gimmick—and there are a lot of gimmicks out there. There is nothing extraordinary about it, it is a normality, it is not surprising. I am surprised by original ideas. Here, everything is predictable and that disappoints me. I don’t believe in these new forms; I don’t have that kind of optimism when it comes to new technologies. New technology is, by definition, always boring because it is predictable, at least to me. In theater, the most impressive is the anthropological discovery of the individual as an abyss. Most of the time, when you don’t know what to do, you fill the space up with new technology which is like a gadget, in my opinion—again, it’s very personal. I’ve never been surprised by new technologies in theater, with robots, etc.—it’s always, “So what?” To me, the idea is fundamental. If someone has an idea with technology, then it works—but it is rare.

SP: Your latest production at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, a staging ofGustav Mahler’s Resurrection symphony, is advertised as a “striking meditation on the exhaustion and disappearance of all things—and takes up in a spectacular way the question of the aftermath: the question of a hypothetical renewal.” Unfortunately, I didn’t have the chance to see it live, I only saw it on the Internet.

RC: Ah, that is not the same thing. I admit it, it was a totally anti-television piece. It was important for the festival to have a document, but it was totally another experience because the hard core of the show was the voids. There was no one there for twenty minutes, and on TV such voids are not possible. When there were holes in the ground, that was the show and there was nobody. And on television that is not possible. On the other hand, I consider it as a documentary—it is not at all the experience that one can have in real time and place.

SP: Yes, there was this screen between me as a spectator and the real experience. However, watching it on the screen I was impressed, if that is the word that can be used here, by stunning similarities between the images that I saw there and those that we see in the media today [i.e., the war in Ukraine]. And I read that you mentioned on more occasions that you conceived those images more than a year ago, so they were purely coincidental.

RC: Yes, that was an awful coincidence, it wasn’t wanted, and it was too late to change the show. Show…it’s not even a show. I was disturbed by this coincidence. I had a doubt whether it was legitimate to show images like that in a moment when there was the same thing going on in real life. I trembled. In the end, we decided with the festival to keep the project as it is, but with a note from me saying that I was sorry by the coincidence that was beyond me.

SP: In a symbolic way, even the place in which this production was presented got its “resurrection,” from being a vandalized and abandoned building to the place that gave birth to an artistic spectacle of the highest quality. Can that coincidence bring any hope for our world today, knowing that everything has its end and a new beginning, or is it just illustrating the tragic circle of never-ending violence and destruction?

RC: Hm… Both. When they offered me to work on Mahler’s Resurrection, they thought of hope. The hope after COVID-19. We were going out again, etc., but I didn’t believe in this kind of optimism. I did not feel that there was a resurrection happening. On the other hand, the word resurrection was the most difficult to interpret. It is literally a resurrection, but a completely human one, so it was necessary to take the anonymous bodies, probably assassinated, out of the ground in order to restore their dignity. So, it was a totally human pietas with bodies coming out of the ground not for a metaphysical resurrection but for a human resurrection. It was not optimistic, but there was a confidence in humanity. However, it is true that it all goes through the image of violence, because violence caused the existence of this mass grave. That was my interpretation of the word resurrection. But it’s true that there was also a resurrection of the place, of the stadium, because it was a dead place. So, there was this double aspect of the word resurrection, a word which is very powerful and very loaded with meaning in our Christian tradition, which is obvious in Mahler’s music; so, it was also a question of giving space to Mahler’s music, and that’s why there was almost nothing to see. After the first chord, it was a question of getting a lot of bodies out of the ground, but there were no particular events, it was not a show, it was not a ballet, it was a moment of contemplation and of listening, deep listening to the music. We don’t see it in the ARTE documentary, but it was important to have half an hour where there was the earth with the emptied holes, e basta (and nothing else). The idea was for the holes in the ground to be like the sepulcher of Christ; there was also a reference to the Christian resurrection, but through these gestures with the bodies, with the corpses, it became not a spiritual thing, but rather a heavy thing and at the same time very much human.

Figg. 5 and 6. Romeo Castellucci, Resurrection, Aix-en-Provence Festival. Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

SP: Since this production was really anchored in the space where it was presented, would you consider producing it in another place?

RC: Yes, there are plans to do it again in another place. I think it’s hard to find a place like this one, but there are possibilities to do it again.

SP: During an interview from ten years ago, [58] you said that in the theater we are hostages or prisoners of the author. Do you still feel that way? And since you are also active on operatic stages lately, where the author of the text is but one of the many personalities involved, does the presence of more than one author make you feel as a double prisoner, or is it liberating in some way?

RC: In the theater that depends on the attitude that one has as a stage director. When we work in a repertory theater, we fall into a faithful attitude, an attitude of respect towards the text, and it is that illustrative, respectful attitude which prevents the imagination and constitutes a cage. In any case, there must be a limit: freedom does not exist in the creation. We need limits. In my opinion, it is a fight that we have with the limits. In combat, it’s good to have boundaries, but outside of an illustrative attitude that’s flat and superficial. It’s about working with the author, but it’s also about a fight to give life back (through our body) to this piece, to this music. Obviously, in opera the already given structure is even stronger, in particular the structure of the tone, because everything is given—music is a temporal meter one cannot escape, not even from rhythm. Personally, there are authors, composers, with whom I cannot work. We resonate aesthetically with certain things and certain names, but it is really a question of entering, imagining, and seeing the same object from our own point of view. The view goes beyond that of repertoire, of habit. We must seek to change the angle of view of the same object. It’s true that the music is a very strong constraint—a very, very strong one.

SP: As a spectator, I found the video in your production of Orfeo ed Euridice most striking, [59] and since there was a direct communication between the stage and the hospital I perceived the video on stage as a usage of the Internet in the sense of an online communication between the singers in the opera house and a participant in the hospital who played the role of Euridice, rather than cinematic use of the video on stage. What was your intention behind it?

RC: It’s true that there was a real-time connection. It was like a ring. Els was in contact with us in the opera house through headphones. She was listening to the music in real time, and we were watching her listening to us, so it was really a kind of ring. But it wasn’t through the Internet, it was broadcast live by a camera connected to an antenna, a signal in the opera house. Every evening, there was the same course in time. The cameraman was in contact with us in the opera house, listening to the music to respect the musical time, to speed up, or to slow down when necessary. The gaze was Orfeo’s gaze. The camera was Orfeo’s eye. It wasn’t really the Internet, it was more of a cinematic language, but it wasn’t even cinema because we used sequence shooting—there was no editing. The shooting was done without any interruption and it was also dangerous if there was, for example, an accident on the road—everything was really fragile and I think that fragility was a strong element in this project.

SP: If I may say you used technology in this production in an absolutely unpredictable way and you’ve created something really revolutionary.

RC: Well, I don’t know about that, but there was a subject in there much stronger than the technology we used. In my opinion, technology must be a tool that needs to become transparent. I’m disturbed when I watch technology-heavy shows, it’s not interesting in my opinion. In this case, it’s true that we used very sophisticated technology, but that was not our focus. The presence of Els was the real thing.

SP: Media often describes your work as shocking. Personally, I haven’t found any of your works shocking nor do I believe that it was your goal or intention, I find it each time deeply moving and truthful, but it is possible that the truth nowadays comes as or seems shocking and that we got very much accustomed to the untruth. Do you believe that it is still possible to shock today’s theater audiences by means of stage imagery?

RC: I don’t know if the word shock is the right word, but I understand what you mean, and I think so. I think we have to… we have to shake the spectator’s body, yes. It becomes more and more difficult, but I think it’s necessary and it’s the right place to do it. We can even use the word scandal, which is a marvelous word, a Greek word. It is necessary to be disturbed in a certain way, but apart from provocation. Provocation belongs to advertising and the media, which must be provocative all the time—so, that’s not a provocation at all because it is still predictable. The shock is to be surprised, to be touched in the intimacy. That is the shock in my opinion. Shock is something that forces you to change your point of view, to reconfigure your view of things—I find that interesting and almost essential.