ARTICLE

Attention, Music, Dance: Embodying the “Cinema of Attractions” *

Davinia Caddy

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 1, Issue 2 (Fall 2021), pp. 35–68, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2021 Davinia Caddy. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss15963.

Who doesn’t love online cat media? Evil Cats, Incredible Singing Cats, Idiot Cats That Will Make You Laugh Out Loud: according to a recent estimate, a segment of the human race shares millions of cat images and videos each day, a global trend that both satisfies and stimulates a fondness for animal acrobatics, all things cute and wasting time, while modelling a liberated uninhibitedness (the cats) and self-facilitated entrapment (ourselves) by rampant corporate surveillance. [1] Particularly off-beat, and potentially off-putting, is a 22-second sequence—readily available on YouTube, the unofficial home of homemade cat media—titled Boxing Cats. Featuring two sparring felines (wearing shoulder harnesses and boxing gloves), a boxing ring (pushed to the very front of the picture plane) and a referee (one Professor Henry Welton, owner of a travelling “cat circus”), this short film dates from the very first crop of cat media to be commercially distributed across the US and Western Europe. This was back in the nineties, at the dawn of a new media age: that is, the 1890s. [2]

It is this originary aspect—the historicity of the pugilistic pair—that interests me in this article. Filmed in July 1894 inside Thomas Edison’s New Jersey-based Black Maria studio, Boxing Cats is notorious not only as the world’s original cat video; it also has been seen to epitomize and encapsulate the so-called “cinema of attractions”—a genre of early silent film first identified and analyzed by film specialists Tom Gunning and André Gaudreault. [3] With minimal editing, a largely stationary camera, and limited depth of field, films of this kind aimed entirely at visual spectacle, foregrounding the act of display. Most of these bizarre products documented live performances (magic tricks, comedy skits, acrobatics, feats of strength) or simulated travel voyages across exotic terrains; others recorded public events (parades, funerals, sporting activities) or different kinds of objects in motion (trains, bullets, knives, waves). Storytelling and character psychology were avoided. Conveying a sense of immediacy and physical presence, the “cinema of attractions” aimed to show not to tell, to exhibit not to explain; as a result, the sense of punctual temporality denied any kind of narrative development, offering little in the way of diegetic coherence, sustained characterization, or causality. Equally significant, for present purposes at least, “attractions” cued a different configuration of spectatorial attention from that of now-standard, story-telling cinema: Gunning calls this “exhibitionist confrontation,” a type of sensory fascination or visceral jouissance that contrasts entirely with classic narrative absorption, its seemingly uncritical transport and panoptic projection into the fictional screen space. [4]

Boxing Cats— preserved as a single 33-foot reel in the archives of the Library of Congress—is exemplary. [5] Clearly, there is no sense of narrative suspense, no linear plotting. (Indeed, the impulse, when watching online, is to click repeat—an action that echoes the workings of Edison’s own film loop system, used in his peep-show-like Kinetoscope.) [6] Instead, the cinematography appears to hypostatize a single, autonomous moment: lighting (from above, a Rembrandt-like luminescence), framing (the ring, a typical frame-within-a-frame), and planar dimensionality (the dark backdrop, conveying minimal depth of field) direct the viewer’s attention towards the fighting cats. As does Professor Welton—or, rather, as does his disembodied head. Grinning, the professor looks directly at the camera, acknowledging the viewer’s presence and seeming actively to solicit our gaze. More like a cinema showman (or is it shaman?) than a sports umpire, the professor performs a wholly pedagogical function, training his cats for the viewers’ scopophilic pleasure.

The visual scene, the technology for capturing and projecting images, the conditions of viewing: these are defining components of what Gunning calls the cinematographic dispositif, a concept that embraces both the material apparatus of early silent film and the attention economy such apparatus appears to endorse. [7] Indeed, in the “cinema of attractions,” on both sides of the Atlantic, the apparatus was arguably the real star of the show, as intimated by firsthand accounts of the earliest Lumière screenings in the 1890s. Recalling what was a characteristic mode of presentation, spectators describe how films were initially presented as still, frozen images, before the projector cranked up and brought the images to life. Here is French film-maker Georges Méliès:

A still photograph showing the place Bellecour in Lyon was projected. A little surprised, I just had time to say to my neighbor: “They got us all stirred up for projections like this? I’ve been doing them for over ten years!”

I had hardly finished speaking when a horse pulling a wagon began to walk towards us, followed by other vehicles and then pedestrians, in short all the animation of the street. Before this spectacle we sat with gaping mouths, struck with amazement, astonishment beyond all expression. [8]

These “gaping mouths,” besides the intensity of physical movement, can act as a useful stimulus: in this article I want to take up the question of whether the “cinema of attractions” might be a useful tool for critical analysis not only of early silent film and its approach to spectatorship, but also of theatrical dance from the period. Certainly, as historicized by Gunning, Gaudreault, and other colleagues, the “cinema of attractions” appears to encode the culture of modernity from which it arose: the onslaught of stimulation, visual spectacle, sensory fascination, bodily engagement, mechanical rhythm, and violent juxtapositions, besides new experiences of time and space now available within the modern urban environment. [9] Moreover, as one of the most popular performing arts of the period, dance was central to the “attractions” industry (and to its origin in variety shows and vaudeville theater), prime raw material that starred The Body in Motion, a favorite fascination of contemporary cinema. [10] It seems inevitable, then, that there was some connective tissue: cinema and dance might not only share subject matter and affective lure; the two might also cue a similar mode of attention or visuality. And yet visuality is hopelessly narrow.

While the topic of attention, as both a historical phenomenon and a theoretical problematic, has risen to prominence across the humanities, it has barely impacted scholarship on music and dance. [11] This is perhaps not surprising, given the fairly recent christening of so-called “choreomusicology,” besides its obvious (if rarely acknowledged) analytical-structuralist inheritance. [12] Yet the topic is surely ripe for questioning. How might we conceptualize dance theater as a form of attention, a perceptual complex embracing not only visuality but also the auditory sense, its cognitive capacities, affective intensity, and imaginative dimension? Alternatively, might dance be understood as a form of address, an exhibitionist regime of intermedial and purely “monstrative attractions”? [13] As for dancers themselves, how can we account for their individual and collective attentive capacities: their visual, aural, kinetic, and spatial relationships to their own music-drenched diegesis? And what has all this to do with the notoriously complex business of representation, invoking dancers’ various figurative, pictorial, decorative, indexical, symbolic, scriptural, or structural functions? [14]

Clues to these questions might emerge from burgeoning conversations outside “choreo” confines: opera studies, for example, has developed a hermeneutical strain of musicology that was fashionable in recent decades, speculating at times wildly on issues of embodiment, materiality, and the senses, besides what Carolyn Abbate once called opera’s “transgressive acoustics of authority.” [15] More immediately helpful in my search for stimulus for this article has been an accumulation of ideas within now-canonic film literature, including Gunning’s and Gaudreault’s many similarly-themed studies, as well as books by Charles Musser and Ben Singer. [16] Before venturing further, though, I need to go back to my primary proposition—that the “cinema of attractions,” as both species of entertainment and discursive construct, might provide some purchase on theatrical dance of the period—and raise an objection, one that readers are likely to have sensed. Cinema, on one hand; theater, on the other: how can we reconcile the two? More specifically, how can we analogize the cinematographic dispositif—its reproductive aesthetic, industrial mechanicity, and silent politics of acknowledgement (embodied in the work of the camera)—to a theatrical and specifically choreographic context? In the pages that follow I want to suggest that music can play a role, can help determine and sustain a particular attentive praxis while pointing to itself—à la Professor Welton—as artifice or contrivance.

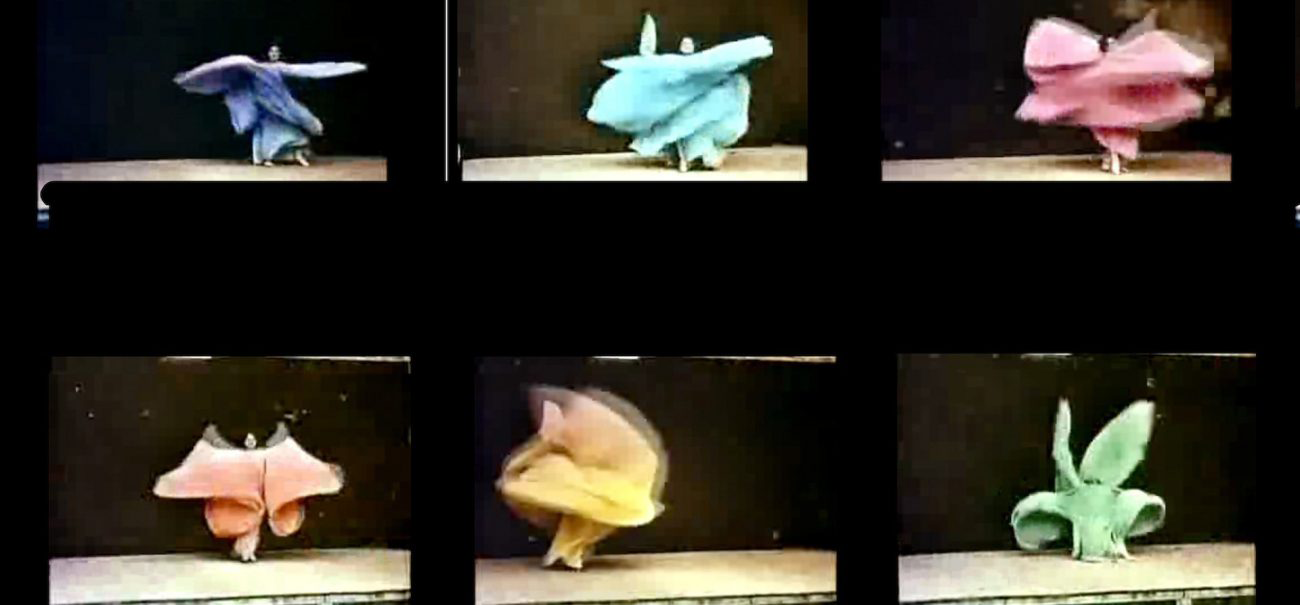

My first and perhaps most obvious example is the American modern-dance pioneer Loie Fuller, known for her multi-colored dance-and-light displays. “Displays,” indeed, is apposite, for Fuller’s was a “dance of attractions”—she whirled giant veils around her barely-seen body while colored lights projected onto her shifting form—that rivalled contemporaneous cinema for novelty and sensationalism. Moreover, like the “cinema of attractions,” Fuller’s dancing was largely without narrative or characterization, besides any sense of linear trajectory. And it, too, was exhibitionary at base, designed to flaunt the spectacular potential not of Fuller’s dancing body, for that body was almost wholly concealed, but of her carefully coordinated props, the huge drapes of cloth attached to baguettes that she twirled, as well as her trademarked electric light inventions. This cinematic potential was not lost on historical observers. Along with phantom voyages and physical comedies, Fuller-style veil-dancing (she had legions of imitators) became popular silent-screen footage—providing a “goldmine” of source material, as noted by French observer Louis Delluc. [17] Perhaps the most famous example is the 1897 short film by Louis and Auguste Lumière, one of their earliest cinematic attempts. A short sequence of silk-swirling by a convincing Fuller look-alike, Danse serpentine captures the striking iridescence of Fuller’s characteristic staged metamorphoses: the brothers tinted the veils of each frame by hand in order to depict the continually changing colored effects (see figure 1). [18]

Fig. 1. Still frames from the Lumière brothers’ Danse serpentine [II], 1897. Lumière Catalogue Number 765,1. © Institut Lumière.

It might seem strange, then, that this cinematic aspect of Fuller’s performance has received relatively little attention in the academic literature on the dancer. [19] Following legendary critics Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Valéry, both of whom wrote about Fuller’s dancing at the theater, scholars have tended to conceptualize a dance of abstractions, envisaging Fuller as an apparition—to Jacques Rancière, a (dis)embodiment of pure potentiality: “the poetic operation of metaphoric condensation and metonymic displacement.” [20] The role of the spectator, according to this line of argument, is primarily hermeneutical: attention is understood as an interpretive effort of sustained contemplation and creative conjecture—a kind of theatrical flânerie or imaginative license to investigate and intensify the mysteries of modern-day popular culture; and also a license that extends to musical experience. Listening to one of Fuller’s shows—she usually performed to preexisting instrumental pieces, familiar to audiences, such as Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries”—was thought to call on an audience’s imaginative insight, provoking a seemingly unending process of interpretation of music and its elusive, ever-shifting meaning. Fuller herself encouraged spectators to “read your own story into a dance, just as you read it into music,” seeming to endorse contemporary accounts of the mobility of musical meaning, the indeterminacy of the orchestra, and the special symbolic quality that her performance managed to exude. [21]

It is doubly strange, then, that this Mallarméan habit of thinking gives way under pressure of enquiry, a recently tapped vein of evidence revealing an alternative reception history. [22] Reports of technical malfunctions, an acutely negative press, defeat in a US infringement suit, rampant commercialization and merchandising: an accumulation of historical sources reveals a kind of gestalt switch, a shift in perspective from envisaging Fuller as a unique, irreplaceable form of semiotic wealth to eyeing her image for its marketable potential, draining her body of that boundless metaphoricity so vaunted by the Symbolists. [23] In this revisionist analysis, attention can be understood as a kind of gawking or badauderie, an incredulity that has been dubbed “the lowest-common-denominator culture of the street.” [24] Indeed, this is the same open-mouthed astonishment that Gunning describes: “the viewer of attractions is positioned less as a spectator in the text, absorbed into a fictional world, than as a gawker who stands alongside, held for the moment by curiosity or amazement.” [25]

As for music listening, evidence suggests that Fuller’s characteristic soundtrack functioned less as a launch-pad for interpretive reverie than as a signature tune or aide-mémoire, a form of branding that circulated in a repetitive orbit, bearing and gathering the authenticating weight not of origination, consent, or any kind of cultural patrimony, but of consumption and commodification, an ethos of multiplicity. [26] Consider, for example, the music used to accompany Fuller’s Serpentine Dance in her first run of solo performances at the Casino Theatre in New York City, February 1892. Ernest Gillet’s Loin du bal was chosen by theater director Rudolph Aronson not for its expressive potential or pictorial associations; rather, the tune, played initially by a single violin in a darkened theater, was immediately recognizable, identifiable, “hummable”—“a perennial drawing-room favorite,” according to an entry on Gillet in Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians. [27] What’s more, when relocating well-known “classical” extracts within her personal design aesthetic (based, as intimated, on the cinematic smack of the instant), Fuller could divest that music of its originary connotations. It is tempting to argue, even, that she metaphorized—or, rather, musicalized—the cinematic practice of gazing at the camera. While filmed “attractions” functioned by acknowledging the facticity of the cinematic apparatus (its mechanics, frames, dimensions, sequencing of shots), in Fuller’s theater, it was music that was factic: bits of Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schubert, and Wagner no longer simulated illusionistic depth or psychological nuance, but rather served to remind audiences of music’s rootlessness and repeatability, its a-signifying potential.

Before we turn to a second “dance of attractions,” one in which music also functions within a quasi-cinematographic dispositif, it will be useful to sketch a contrasting or, even, contrary example: an example where narrative and causality define onstage activity, voyeurism, and identification, and where dance music functions as an integrative component of a theatrical diegesis—if you like, as pure suture. If, in the above case, visual and auditory attention can be understood as a kind of gawping or incredulous amazement, here a form of what we might call “fictive absorption”—enabled by visual design, gesture, and music—characterizes the spectatorial experience. Or perhaps “conventional fictive absorption” is more appropriate, because this kind of spectatorship, and this kind of music, has of course a long and illustrious history.

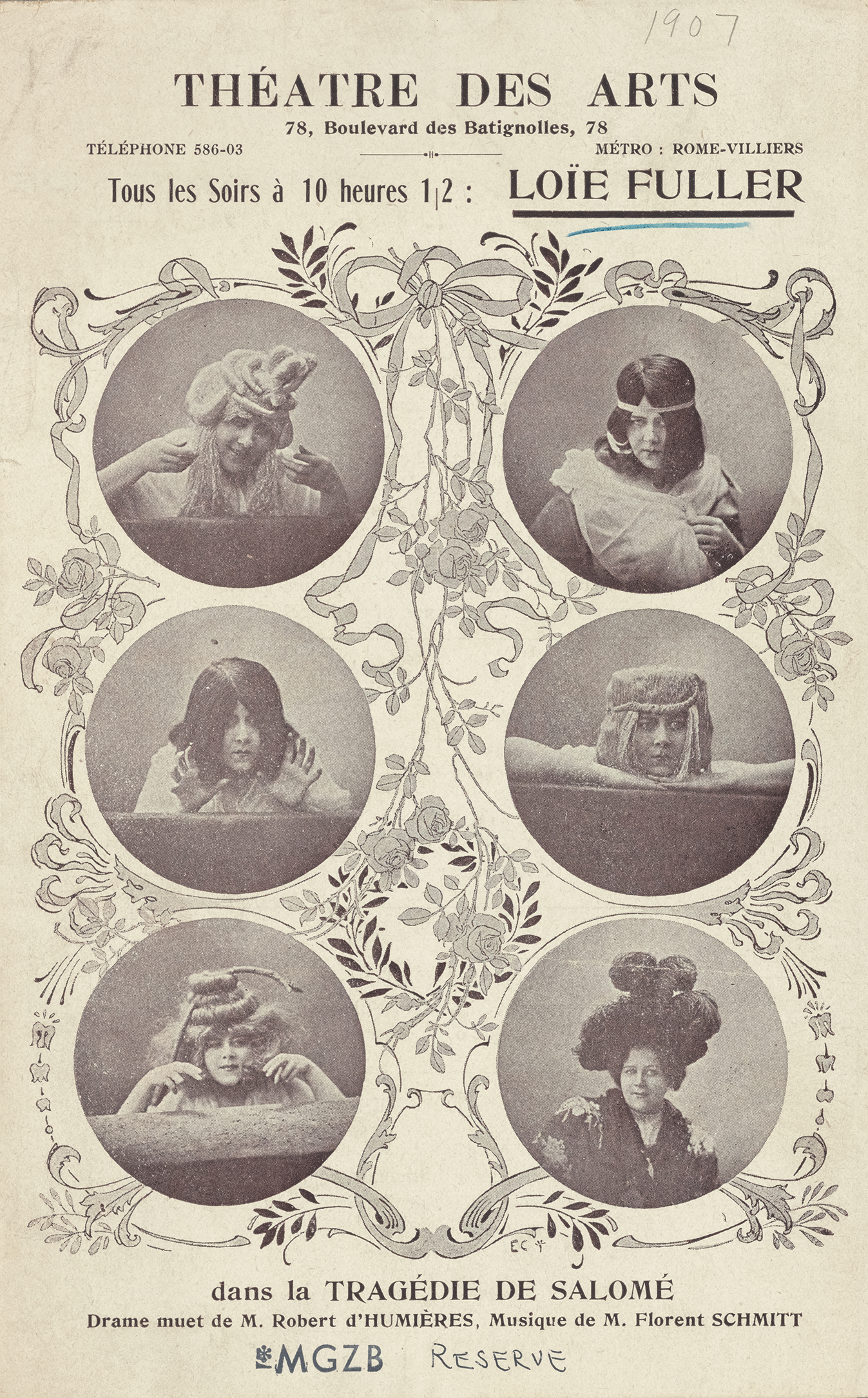

It is “La Loie,” perhaps ironically, to whom we can turn once again, here in a theatrical performance that flashes red in the dancer’s history. Unlike her typically abstract and decorative displays, Fuller’s production of La Tragédie de Salomé, premiered at the newly renovated Théâtre des Arts in Paris on November 9, 1907, was dramatic through and through. Based on a libretto by theater director Robert d’Humières and a newly commissioned score by the young French composer Florent Schmitt, Fuller’s “drame muet” (silent drama) comprised seven scenes, each designed to illustrate a particular aspect of the Judean princess’s changing character. Carefree and coquettish in the “Danse des Perles”; proud and haughty in the “Danse du Paon” (peacock); sensual and sinister in the “Danse des Serpents”; cold and cruel in the “Danse de l’Acier” (steel); lascivious and perverse in the “Danse d’Argent” (money); and terrified and delirious in the “Danse de la peur” (fear): Fuller portrayed them all (to varying degrees of success, according to contemporary observers), as can be seen in figure 2, the program front cover, with its six studio headshots—some distance from standard Fuller iconography. Moreover, besides these carefully choreographed in-character dances, the production offered a strong and detailed plot, replete with fin de siècle decadence and female seduction, as well as impressive scene and costume changes, including an outfit made from 4,500 peacock feathers, a six-foot artificial snake and a sea that turned to blood.

Fig. 2. Program cover, La Tragédie de Salomé, Théâtre des Arts, Paris, 1907. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 12, 2021.

In terms of conveying the drama, Schmitt’s score did more than its share of heavy lifting. Praised in the press for its “skillful” and “sumptuous” orchestration, the music—dedicated to Igor Stravinsky—was thought to offer a “symphonic description” of the developing goings-on: [28] it supplied the unspoken words of the drama, conjured the somber mood, added a touch of mystery, and expressed the lascivious perversity of the dancing. [29] To one commentator, moreover, it simmered with an inner life that not even the onstage choreography managed to incarnate: Schmitt’s score almost single-handedly evoked the “demonic phantasmagoria,” besides the numerous cataclysmic events that unfolded throughout the drama. [30]

Clearly, the music was dramatically contingent, an integrable part of the stage diegesis, and one that succeeded in enabling shifting identifications, variously binding spectators into the fiction. Consider, for example, the sixth scene (“Danse d’Argent”), which begins with Salome performing a diegetic dance before Herod. This was a typical “attraction,” we might suppose: indeed, the dancing seems purely exhibitionary, designed to be displayed; and the music seems to endorse this diegeticism, its melodic patterning, textural clarity, and rhythmic propulsion setting apart the stage spectacle within the scene. Yet the dance tune—shrieking woodwind sixteenth notes, punctuated by off-beat string and brass chords—screams Salome: it is a melodic inversion of the opening motif of the work, performed to a closed curtain, an undulating line in the cellos and basses that offers a sonic inscription of the dancing body absent from the stage. Here in the sixth scene, this formerly floating signifier takes corporeal form: it is, as it were, territorialized, bringing to the diegetic display a heavy dose of dramatic character, and one with which spectators are invited to identify.

But identification is soon skewed. After only two bars, this diegetic dance is interrupted by a change of musical motif: blazing sixteenth notes are swapped for a drawn-out and sustained crescendo previously associated with Herod, just as—according to the stage directions—Herod himself gets up out of his seat. The two motifs jostle as Herod moves towards the dancer, grabs her, even throws himself on top of her, stripping her of her clothes. Salome lies naked on the floor, Herod’s motif blaring from the upper winds and strings, repeated no less than fourteen times (at rising pitches and in various rhythmic diminutions). The message here—what the music is insisting on with all its repetitions—seems clear enough. To gain maximum impact, not only does Salome have to be naked; she has to submit to patriarchal musical discourse.

Whatever we might think of this gendered argument (and its resonance across a vast terrain of Salome-themed scholarship), music’s dramatic contribution—its interdependence with gesture and visuals—seems assured. [31] Even the most cursory analysis of Schmitt’s score reveals a striking incongruity within Fuller’s choreographic output: while her typically abstract dances paraded music as a mere postulate, an empty and de-territorialized signifier, her Salomé featured a specially simulated soundtrack, tightly interwoven with choreography and dramatic action. Moreover, as press critics suggest, listening to that soundtrack involved a kind of figural entrainment: figural, as in bound to forms or characters derived from life; entrainment, as in a process through which we as distanced spectators are incorporated into the diegesis and, as a result, invited to assume ideological complicity. Broadly speaking, this process itself can be conceptualized as an aural equivalent of the “optical visuality” described and historicized by film scholar Laura U. Marks (leaning on art historian Alois Riegl): a voyeuristic practice of dominance and control, associated with the emergence of Renaissance perspective, in which spectators distinguish figures as distinct forms within an illusionistic space, before imaginatively projecting themselves into that space. [32] Certainly, it is a mode of listening that, while traditional, falls some distance from the open-mouthed astonishment of the “attractions” industry. Indeed, the latter has more to do with what Marks identifies as “alternative economies of looking” associated with the “cusp of modernism,” economies in which the spectator relinquishes mastery over what is seen and heard in favor of an immediate embodied response. [33]

Modernity, Metropolis, Monstration

My second “dance of attractions,” as heavily mythologized as the first, encapsulates precisely this perceptual economy; in doing so, moreover, it rivals early cinema as a distinct aesthetic practice. To be sure, the conceptual origins of productions such as L’Oiseau de feu, Pétrouchka, and Le Sacre du printemps—staged in the early twentieth century by Sergey Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes—are thought to lie principally within Russian music theater and folk history. Since the pioneering efforts of Richard Taruskin in the early 1980s, scholars such as Tatiana Baranova Monighetti and Olga Haldey have located models for the troupe and their productions in Russian folk song, the Mir Iskusstva circle, and Savva Mamontov’s private opera, to name a few. [34] Yet the “cinema of attractions” might provide an alternative optic through which to view—and to hear—the famous Russian company, off-setting now-familiar claims of Russian primitivism with a vision of Euro-American modernity, distinctly urban, technological, and vernacular. [35] Suggesting this is not to deny the decade-or-so discrepancy between the two: the fact that, by the time of the Ballets Russes’s theatrical ascendancy in the early 1910s, the “cinema of attractions” had, according to Gunning, sunk “underground,” magic acts, moving trains, and other purely exhibitionist displays replaced on film by the narration of stories set within self-enclosed fictive worlds populated by relatable characters. Nonetheless, early cinema engendered an urban modernity—a particular experience described in terms of novelty, mobility, instability, and physical sensation—that continued to find expression, if not on screen, then in amusement parks, circuses, waxwork museums, postcards, posters, and, we might argue, music theaters. [36] Moreover, despite the superseding of “attractions” by narrative film in the second decade of the century, its perceptual possibilities became the focus of film-theoretical discourse in the 1910s (and into the 1920s). As the Ballets Russes were winning audiences in London and Paris, the first film theorists on both sides of the Atlantic were contemplating new kinds of knowledge, feeling, and sensation that (they thought) only cinema could create, cinema lauded not for its realism or objectivity, but for its radical possibilities of perception.

Perhaps my particular example from this repertory will not surprise. Of all the Ballets Russes’s pre-war productions, Le Sacre du printemps is the most obviously monstrative, non-narrative, and confrontational: it is a ballet, at base, about the act of display. What’s more, in its ability to circumvent a developmental trajectory, Le Sacre is marked by the same kind of formal non-continuity, dynamism, and flux that characterizes the “cinema of attractions.” It too aestheticizes the effects of modernity on city life, proceeding by means of temporally disjunct bursts of presence, eruptions of activity that signal what Gunning describes as “the present tense” of pure display. [37] Musicologists have long pointed to the defining compositional principles of Stravinsky’s score, describing musical disjunctions and unsignaled interruptions as typically Russian: according to Taruskin, examples of drobnost’, the quality of splinteredness or fracture, of a whole being the sum of unrelated parts; and nepodvizhnost’ or immobility, a moment-by-moment absence of any forward-going motion. [38] Yet these principles are also emblematic of early silent film. Take, for example, the multi-shot films of Georges Méliès, in which, according to historian John Frazer, “causal narrative links … are relatively insignificant compared to the discrete events. … We focus on successions of pictorial surprises which run roughshod over the conventional niceties of linear plotting. Méliès’ films are a collage of immediate experiences which coincidentally require the passage of time to become complete.” [39] Collage as a structural technique (with distinct temporal ramifications) can also be associated with Le Sacre, which—as mentioned a moment ago—is characterized by the abrupt juxtaposition of musical ideas separated in time and space (register, texture, timbre, or instrumentation). [40] Indeed, the manner in which Stravinsky’s music foregrounds its own formal apparatus—devices of superposition, stratification, and what Pierre Boulez famously called “false counterpoint” [41] —is also reminiscent of the “cinema of attractions,” known not only for its characters’ self-conscious gazing at the camera, but also for its promotion of the latest technological machinery, often over and above the visual content to be displayed.

Before drawing any further analogies in terms of spectatorship or attention, it might be useful to lend some specificity to this generalization about apparatus. To recall an earlier argument: in Fuller’s typically non-narrative productions, music’s overt familiarity—its function as a signature tune wiped of pictorial or expressive meaning—engendered an equivalent to the aesthetic of acknowledgement (the staring at the camera) characteristic of the “cinema of attractions:” put bluntly, her music drew attention to itself as part of the artifice of presentation, the theatrical spectacle. In Le Sacre du printemps, I argue, this same effect is created but by quite different means. For while Fuller’s dancing seems to have proceeded regardless of her musical accompaniment, the dancers in Le Sacre betray a striking receptivity to theirs. Indeed, such is the nature of this receptivity that the dancers function as another kind of mediating technology: an apparatus for the inscription of music as visual pattern and visceral force.

This idea of the dancers in Le Sacre as some kind of technological apparatus is not new. [42] Critics at the premiere described automatic and reflex movements, as well as an overall sense of dehumanization: [43] even the choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky admitted in a 1913 interview that “there are no human beings in it.” [44] Scholars and practitioners over the years have tended to agree, showing in careful and detailed analyses how Nijinsky’s choreography was strictly coordinated to Stravinsky’s underlying musical pulse, as well as to the complex play of rhythmic counterpoint that unfolded across it. [45] In “Rondes printanières” (Spring Rounds), for example—and as Stravinsky himself indicated in his choreographic notation—one group of dancers moves to the syncopated rhythms of one musical motif, while a second group accents the downbeats of another. Earlier in “Les Augures printaniers” (The Augurs of Spring), this choreo-musical interplay is visualized within the body: while the dancers jump to the musical downbeats, their arms and upper bodies bring out the music’s irregular accents.

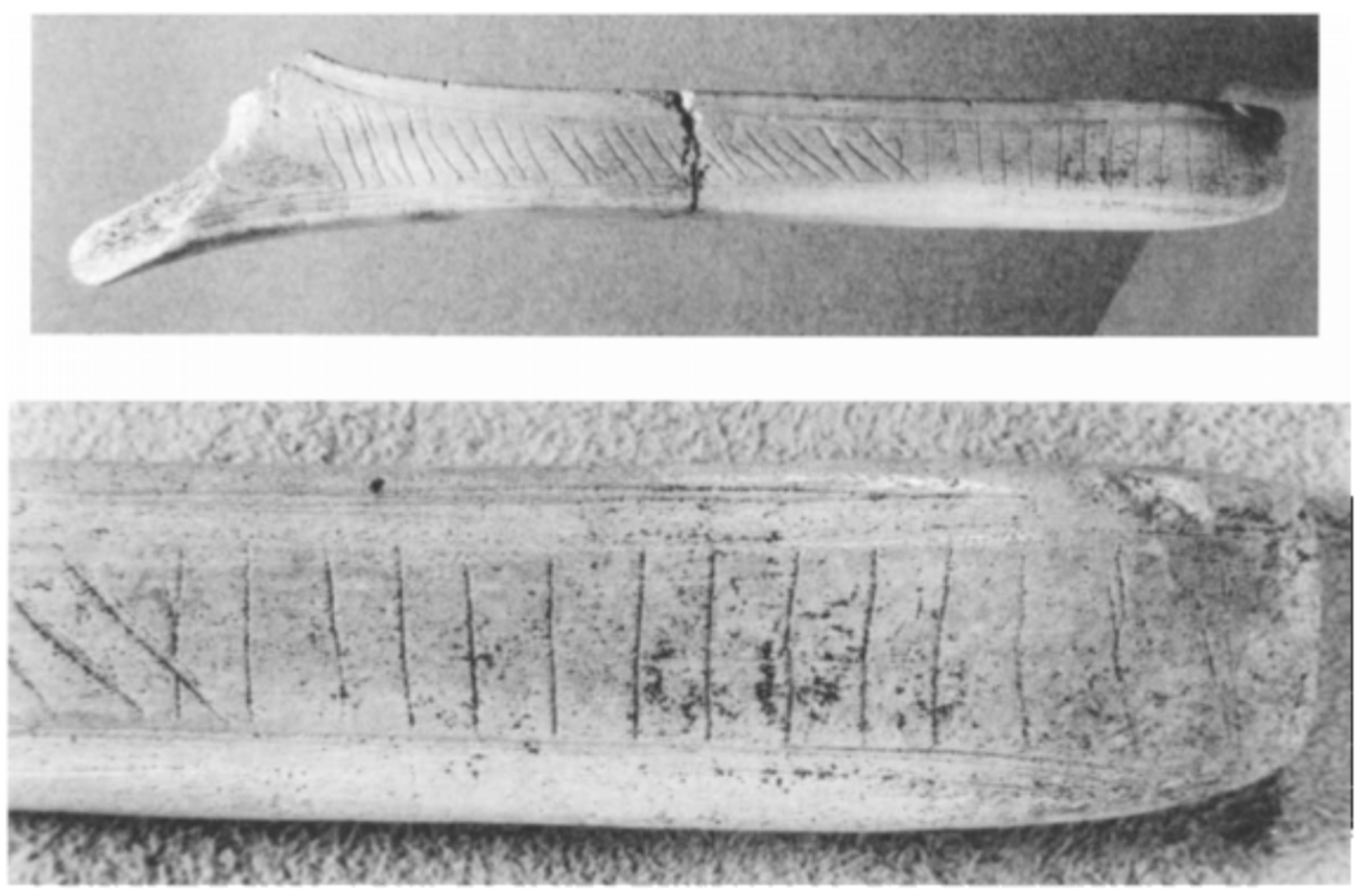

Underlying these examples is what we might call a poetics of workmanship, a model of the body as a laboring machine. But it might be useful to speculate further on the type or kind of machine we tend to envisage—such speculation might help us, now over a hundred years after the premiere, towards a more nuanced conceptualization of the original interrelations between music and dance. On the one hand, prompted by the ballet’s setting and scenario, it is tempting to conjure up the very earliest technologies of inscription: prehistoric bones, rocks, or other hard materials incised with series of notches, marks, or tallies. Clearly, visual artefacts such as figure 3—a broken baton from the Grotte du Placard, dating from Magdalenian IV (approximately 15,000 years ago)—have nothing to do with pictorial representation; they are evidence, instead, of the abstract origins of counting, a one-to-one correspondence between a notch and, say, the sighting of an animal or the appearance of the moon. This singular correspondence, as archaeologists have revealed, likely involved neither physical resemblance nor abstract numeration: no stories or words accompanied the notches; nor were they necessarily conceived mentally as incremental numbers. The notches simply recorded single, unitary events: one animal or moon, one mark. [46]

Fig. 3. Magdalenian perforated baton, Grotte du Placard (Charente, France), PL 55064. Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. © Alexander Marshack.

Is it possible for us to envisage Le Sacre as a similar technology, a form of prehistoric inscription that exists outside any and all pictorial, symbolic, and narrative domains? To follow this thread might be to recall the anecdotal history of the ballet, replete with tales of counting: Nijinsky, at the premiere, screaming the number of beats from the wings; [47] dancers trying to internalize complex meters (that often departed from notated musical ones). [48] We might also look afresh at the bent-over “stamping” motion—the hunkered-down bodies—that characterizes the ballet, at least in “Les Augures printaniers”: for what is this episode if not the ritual demonstration of non-figurative tallies, series after series of stubbornly illegible, meaningless notches inscribed onto three-dimensional space?

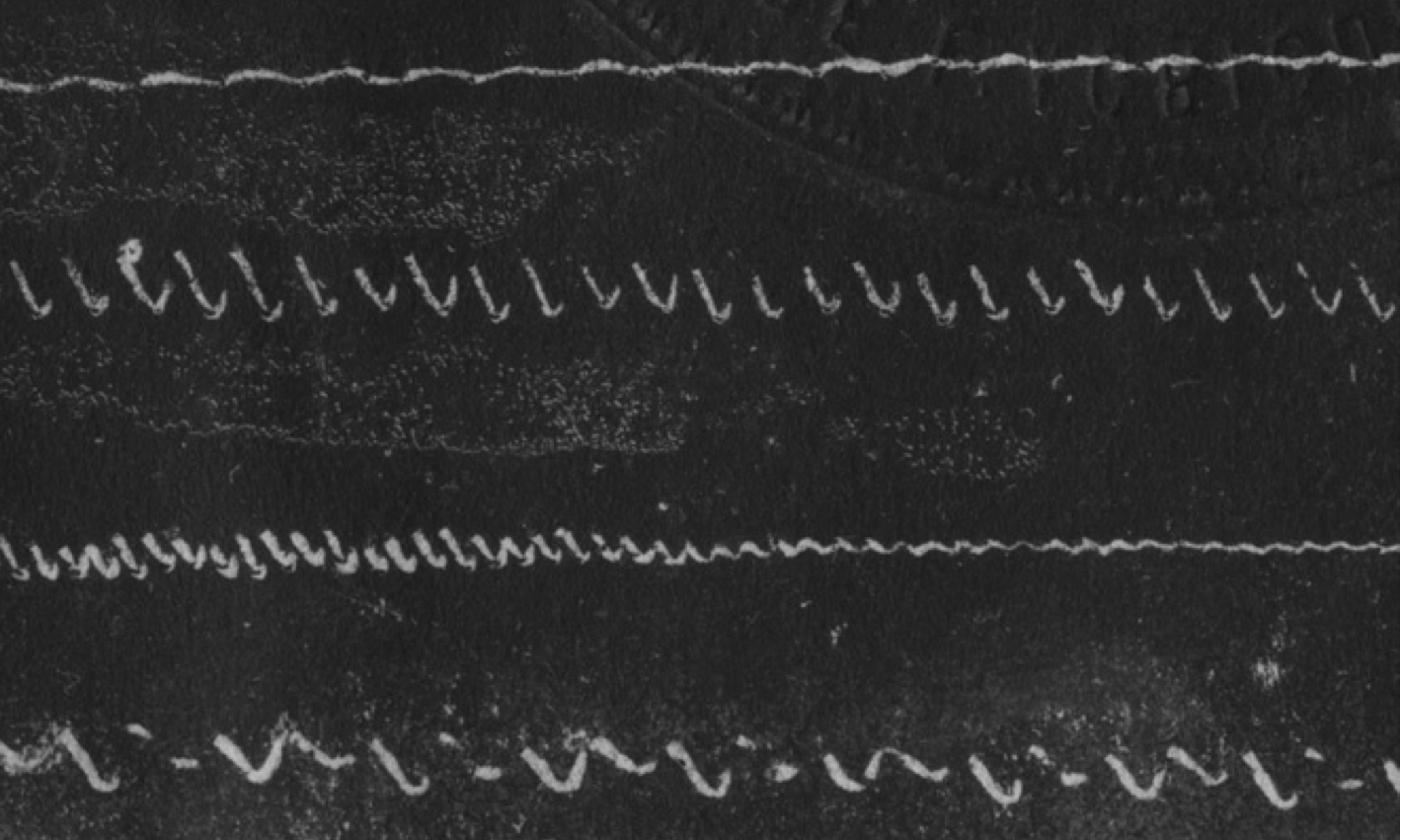

On the other hand, attending to these notches—to a system of inscription that runs against our tendency to interpret images as signs or narratives—might lead us towards the opposite end of the historical spectrum: that is, to much more advanced apparatus. Recent commentators have argued that Le Sacre fractures and fixes bodily movement in a manner similar to contemporary technologies of visualization such as early film and chronophotography, the name given by French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey to his method of capturing separate frames in succession and then graphically inscribing them alongside each other. [49] But, more important for present purposes, the ballet also fractures and fixes music, picking apart melodies and metrical systems, then rendering them as discrete, measurable units. The choreography, perceived in this way, might be envisaged as a particular type of machine, a sound-writer or phonautograph [CGL1] —the first instrument devised to inscribe the movements of a taut membrane under the influence of sound. Indeed, early technologies of sound recording (i.e., not playback) were understood as predominantly visual apparatus: they translated soundwaves into series of etches or grooves, a type of visual patterning not unlike the notches and tallies described above (see figure 4). [50]

Fig. 4. Detail of a phonautogram by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, Phonautographie de la voix humaine à distance, 1857. INPI. Credits: FirstSounds.org.

Of course, “reading” any modern art—literature, music, theater—against a backdrop of contemporary technological invention is a now-trending critical maneuver. Inspired by the work of Friedrich Kittler and, more recently, Sara Danius, scholars readily assume a dialectical relationship between technology and early modernist aesthetics: the two, we are led to believe, are co-constitutive. [51] The nub of the argument here seems to relate to the dancers’ perceived internalization of a technological mode (however prehistoric or modern we consider the apparatus): that is, their function as a sensory-perceptual machine, a technology of musical inscription that filters, segments, and registers sound as a series of atomized quanta. There is also a more basic point here: according to this argument, the dancers are defined phenomenologically not in terms of their visual capacity, as we might expect following traditional Enlightenment notions of self and narrative, but in terms of audition—hearing is thematized onstage, is privileged as a perceptual phenomenon.

This point also resonates across the literature. Recent studies, particularly within literary criticism, have explored the heightened significance of sound and auditory experience in modernity, gesturing not only to the development of various acoustic technologies in the early twentieth century (the telephone, phonograph, and later radio), but to an emerging affiliation between the self and the ear—what Steven Connor calls “the modern auditory I.” [52] Indeed, at a time when increasingly complex visual apparatus brought into question the reliability of the naked eye, threatening a continuity between seeing and knowing, the ear opened up a new and different way of engaging in the world, a mode of lived experience defined in terms of presence, immediacy, and embodiment. More specifically, as Connor explains, if the visual self can be conceptualized as a single perspective from which the exterior world opens up in three-dimensional certitude, the listening self is defined “not as a point but as a membrane, not as a picture, but as a channel through which voices, noises and musics travel.” [53]

Connor provides another—and especially useful—analogy, one that might well recall the above description of Le Sacre’s hunkered-down bodies, nudging us further towards that argument about the dancer as a laboring machine, an intermediary apparatus through which “noises and musics” pass. We could push the argument further by suggesting that Le Sacre stages the “modern auditory I”: that, like literature by Auguste de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Marcel Proust, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (and, later, Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf, and James Joyce), the ballet uses sound and auditory experience to subvert traditionally ocular conceptualizations of subjectivity, in doing so modelling a new kind of phenomenological experience. Indeed, if as Connor writes “visualism signifies distance, differentiation and domination,” then audition implies intimacy, immediacy, and immersion—a way of being in the world that appeals directly to the body and the senses. [54]

Connor’s words are further instructive in that they provide a useful segue into the topic of attention: that is, the auditory experience of bodies in the audience, as well as those onstage, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, on the evening of May 29, 1913. There is of course an embarrassment of literature about spectators’ response to Le Sacre, of which a good deal, particularly interviews and memoirs written many years after the premiere, has been exaggerated for effect. Historians, perhaps inevitably, have made much of the “tumultuous demonstrations”: [55] the hissing, snickering, shouting, laughter, whistling, hushing, and applauding of an audience seemingly divided into strongly opposing camps. But efforts have also been made to get to the facts, in particular, the consternation felt with regard to Nijinsky’s choreography: whereas Stravinsky remained well respected and highly esteemed by the bulk of the audience (the composer was merely heading in the wrong direction, having “compromised” himself by working with Nijinsky), the choreographer was subjected to a barrage of criticism, his choreography labelled “ugly,” “monotonous,” and “tedious.” [56]

Less has been made, though, of two features of critics’ reviews that strike a resonant chord with Connor’s words, above. One is the sense of overall astonishment reported, an astonishment that no doubt contributed significantly to the infamous “ruckus,” but also to a critical loss for words. A number of commentators in the daily and specialist press acknowledged that Le Sacre seemed designed to shock, confuse, and startle; [57] some confessed their own professional bewilderment, admitting that they couldn’t express an opinion, couldn’t even understand the work, and couldn’t work out whether it was a masterpiece or not. [58] Certainly, there was a shared sense of critical non-comprehension: an inability to register, contemplate, and compare the ballet to works of a more assured and collectively approved greatness. [59]

This feature of the reviews, which might seem ironic in view of later attempts to co-opt Stravinsky’s score into an emerging aesthetic of “cérébrisme,” [60] comes into greater clarity when viewed alongside a second feature: critics’ visceral reactions to the ballet. For while their mental and intellectual capacities may have been compromised, commentators registered acute sensory stimulation. To be sure, this kind of intense physiological response was not unusual in the face of a Russian extravaganza. Describing, at the outset of his Le Sacre review, the effect of Diaghilev’s first Parisian ventures, composer-critic Xavier Leroux writes:

We trembled on our legs like drunken men as golden pinwheels and diamonds danced before our eyes, as our temples pounded. Slowly we emerged from this state of numbness; and with our bodies still blue with ecchymosis we could finally reopen our eyes in which a thousand phosphenes were exploding. [61]

Others thought—or rather sensed—in similar ways. Le Sacre brought about “an absolutely new feeling,” a feeling “never before experienced and of the most incisive acuity.” It had an “overwhelming,” “intoxicating,” “suffocating” effect: it “crushes us”; it “knocks us flat.” [62] In a long and perceptive review, Jacques Rivière elaborated further. To Rivière, the “oddities” of Stravinsky’s score in particular were designed not to startle or to provoke admiration, but, rather, “to put us into direct contact, into immediate communion with the most wonderful and amazing things”: “[they] bring us close … to introduce us to the object on an equal footing.” [63] That “object,” we learn, is “the passions of the soul”:

We are brought closer to them, we are led into their presence in a more immediate way, we contemplate them before the arrival of language, before they are hemmed in by a host of innumerable and nuanced yet chattering words. … In the dark night of the intelligence, we are aware; we are there with our body, and it is that which understands. [64]

Presence, immediacy, embodiment: this is a tantalizing proposition, and one that echoes Connor’s words on the lived experience of the “modern auditory I,” a condition shot through with visceral reactions and almost erotic stimulation. Are we to imagine, then, a shared mode of sensory receptivity—symptomatic of a self immersed in the world—both on stage and off? Are the spectators in the theater to be aligned, in their mode of auditory attention, with the dancers pounding the floor? Aligned might be the wrong word to use here, for at issue is the collapse of conventional boundaries between spectator and spectated: the capacity of auditory experience to disintegrate and reconfigure space. For the self as membrane, we might argue, spills out over the stage and into the stalls: with a marked auditory consciousness, that self enjoys direct, untrammeled access to the world, an affective experience that is inherently embodied and intersubjective.

It is tempting to describe this experience in terms of haptics, a relatively modern term, trending across phenomenology and film studies, that emphasizes proximity and mutually constitutive exchange: that is, a sense of reciprocity between subject and object, the former an active agent in a corporeal and quasi-erotic encounter with the latter. Laura U. Marks, mentioned earlier, has proved highly influential on the subject, exploring the remit of what she calls “haptic visuality,” a mode of experience in which the eyes function like organs of touch. Marks’s seminal study The Skin of the Film investigates “haptic aesthetics” in relation to a specific kind of intercultural cinema, a genre that, dealing with “the power-inflected spaces of diaspora, (post- or neo-) colonialism, and cultural apartheid,” appeals to an intimate, embodied viewing experience—the sensory and affective process of coming into contact with the skin of the film text. [65]

Marks’s work is not only interpretive, not only concerned with the fundamental nature of the decisions we make about how films embody meaning. It also has a valuable historiographical dimension aimed at loosening the grip of art-historical narratives that uphold the superiority of Western illusionistic representation. “Haptic aesthetics,” she explains, emerge within distinct cultural historical periods, such as modernism, when “meaning came to reside in the embodied and intersubjective relationship between work and viewer or reader.” [66] Referencing a “modernist revaluation of tactility” (“the return of materiality to the mediums of art and literature”), Marks identifies the modernist period with a flare up of interest in the subjectivity and physiology of vision, gesturing towards her broader attempt “to redeem aesthetics from their transcendental implications by emphasizing the corporeal and immanent nature of the experience of art.” [67] Particularly important within Marks’ analysis, at least for present purposes, is a case singled out for its overt haptic dynamics: “the early-cinema phenomenon of a ‘cinema of attractions,’” a genre that, according to Marks, appealed to an immediate, “embodied response.” [68] Enabling what she calls “bodily identification,” rather than “narrative identification,” the “cinema of attractions”—as Gunning has not tired of telling us—addressed spectators directly, sometimes exaggerating the sense of confrontation such that it takes on the quality of a physical assault. [69] Contact between subject and object, not mimetic representation, was the source and means of meaning constitution; distanced identification was substituted for the immediacy and intersubjectivity of sensory perception.

An Aesthetic of “Attractions” (Conclusion)

Marks thus steers us back towards the framing analogies that this article has sought to elaborate: at base, between the “cinema of attractions,” Fuller’s dance theater, and the Russians’ Sacre du printemps; and between all three and the phenomenology of the modern metropolis. The first analogy, as I hope to have shown, is based not only on an equivalence of structure (fractured), temporality (disjunct), teleology (denied), narrativity (also denied), presentational mode (exhibitionary), and representational aspect (non-figural); parallel modes of attention (immediate, embodied, haptic, immersive) and experience (non-identificatory) can be discerned within historical source materials and envisaged in a hermeneutical sense. This is not to mention the positioning of music, in the two dance examples, as artifice, apparatus, or mediating technology—the sonorous equivalent of Professor Welton’s frontal stare: silent cinema’s aesthetic of acknowledgement. Indeed, I would argue in favor of this musical equivalence despite radically different means. To put this other words, how both examples establish and sustain a similar musical disposition differs drastically: Fuller tends to disregard her music’s expressive connotations, but powerfully foregrounds that music’s status as a signature tune, an artificial component of the theatrical spectacle; Le Sacre also foregrounds music as part of an apparatus of presentation, but does so by means of an intensity of inscription, a battery of music-movement alignments that suggests a distinctly modern and auditory phenomenological experience.

In closing, I want to raise, albeit briefly, some further considerations on the historical stakes of my analogies. Following Gunning, Gaudreault, and others, I have presented “attractions” as unique to the early twentieth century, a contingent product of a specifically modern experiential landscape defined in terms of mobility, flux, incredulity, novelty, non-continuity, and perceptual change. Yet this claim surely oversimplifies: what, we might ask, of the emergence of “attractions” in other periods and genres? The cinematic “attractions” of Sergei Eisenstein’s montage practice, established in the early 1920s, come immediately to mind, as do the operatic “attractions” of nineteenth-century Italy (say, the typical Rossinian cabaletta), twentieth-century Brechtian theater, besides the “acinema” of Jean-Francois Lyotard’s philosophical imagination. A more obscure example might be the so-called “theater music” associated with the ancient Greek dithyramb—a choral hymn to honor Dionysus. This musical genre conforms almost exactly to the “attractions” template, with an emphasis on display, innovation, and variety, a formlessness of structure, an irregular temporality, an ethos of conscious display, and an appeal to the senses not to the intellect. [70]

What if we were to embrace these far-flung examples as a call to envisage the “attractions” model not as a locus of stability or fixed meaning, but rather as an impulse of change, transformation, and mutability? Charting “attractions” across historical periods and places might well unlock dimensions of significance that help us chronicle emergent practices of looking, listening, and spectating, as well as, in a formal-aesthetic sense, shifting modes of presentation, enunciation, intermediality, and address. This call to problematize the cinematographic dispositif might also lead inwards: that is, to a realization of the variability or transmutation that can emerge within a single work. In the case of Le Sacre, my thoughts on the hunkered-down “stamping” might well prompt a comparison of ballet and early cinema; but this comparison cannot be sustained across the entire work. To me at least, the very opening of the ballet does indeed epitomize the “attractions” aesthetic: the bassoon, acting as a kind of cinematic barker or bonisseur, accustoms the audience to a state of shock, its musical discourse (non-continuous temporality, wandering structure, agglutinative development, undisciplined rhythm

and meter, as well as the uncertainty and variability of sound production) a means of mediating the theatrical “attraction” to follow. [71] But then there is the very end, the Chosen One’s Sacrificial Dance. Some commentators (Taruskin, Adorno) have described the vacuous dance of a helpless individual—Stravinsky’s “Great Victim,” the original title of the work—willing to sacrifice herself “to the collective,” “without tragedy” and through “self-annihilation.” [72] With an emphasis on shocks, reflex actions, and physical immediacy, as well as Stravinsky’s musical “hypostatization,” this now-standard description evokes a Chosen One acted upon by the theatrical apparatus—evokes an aesthetic of “attraction,” we might argue. [73] But what about an alternative perspective (following Tamara Levitz’s nuanced and historically sensitive scholarship) that emphasizes the communicative potential of dance, the emotional experience of the spectator, and Nijinsky’s/the dancer’s angry passion? [74] This line of interpretation might endorse the very opposite of the “attractions” principle—namely, narrative and causality, distanced identification, listening as that kind of “figural entrainment” described earlier.

Going further might raise the issue not of identifying opposites and generating labels, but rather of sketching the displacement process: the ways in which dance theater reshapes a cinematographic dispositif in its primordial dimensions; and, in doing so, produces new and heterogeneous subjectivities. While the concept of subjectivity has remained under the surface of this study, it surely demands interrogation, if only as a way of deconstructing basic dualisms such as activity and passivity, subjugation and domination, identification and estrangement, absorption and theatricality. With this last pairing, one that gestures to the landmark art-historical work of Michael Fried, I may have stepped into perilous waters: [75] How does the concept and practice of theatricality—the assumption of objecthood and attendant self-consciousness of viewing—relate to the cinematographic “attraction”? Does absorption, into a kind of transcendental sphere, necessarily imply identification, what I loosely described as “figural entrainment”? What sort of phenomenological engagement might be shared by viewers of painting and performance art, and spectators of cinema and ballet? And how does art, not to mention Fried’s “non-art,” variously disclose, uphold, and subvert the positions and activities of its beholders? On these questions, as on the matter of subjectivity/-ties, there is much work to be done, work that might well be both extensive, invoking multiple genres or media, and foundational, grappling with longstanding issues of art, its ontological reality, agentive qualities, signifying regimes, and psychic address, not to mention its in-built concept of the spectator, their sensory perceptions, and physiological orientation. This is not to mention the significance of what is nowadays a loaded business, “context”: in the present case, the distinctly modern and newly sensualized spectacle characteristic of the Western metropolis. I hope that the wide-angled searching for conceptual equivalence attempted in this article might be productive going forward: on the one hand, it might help open up our subjects of study to truly interdisciplinary critique; on the other, it might prompt us to refine and refocus our attention on music and the intimations of meaning that flow from it.

* Sections of this article were presented in preliminary form at the 20th Congress of the International Musicological Society (University of the Arts, Tokyo, 2017) and the Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society (Rochester, NY, 2017). I am grateful to the audiences at both presentations for their thoughtful and stimulating comments. This article has also benefited from close readings by Maribeth Clark, Roger Parker, Emilio Sala, and my anonymous reviewers.

[1] See Harriet Porter, “Why Cool Cats Rule the Internet,” The Telegraph, July 1, 2016.

[2] A 2015 exhibition at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image— How Cats Took Over the Internet—celebrated the history of cats on screen: see reviews in the New York Times (August 6, 2015), the Guardian (August 7, 2015), and TIME Magazine (September 22, 2015). For a nuanced account of the feline take-over, see E. J. White, A Unified Theory of Cats on the Internet (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020).

[3] See Tom Gunning, “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant- Garde,” in Early Cinema: Space Frame Narrative, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (London: British Film Institute, 1990), 56–62. Gunning’s second essay on the topic is “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator,” Art & Text 34 (1989): 31–45. See also André Gaudreault and Tom Gunning, “Le cinéma des premiers temps: un défi a l’histoire du cinéma?” in Histoire du cinéma: nouvelles approaches, ed. Jacques Aumont, André Gaudreault, and Michel Marie (Paris: Sorbonne, 1989), 49–63; Eng. ed. “Early Cinema as a Challenge to Film History,” trans. Joyce Goggin and Wanda Strauven, in The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, ed. Wanda Strauven (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), 365–80.

[4] Gunning, “Cinema of Attractions,” 59; also see Gunning’s entry “Cinema of Attraction,” in Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (London: Routledge, 2005), 124–27.

[5] Henry Welton, The Boxing Cats (West Orange, NJ: Edison Manufacturing Co., 1894), video, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[6] See Ray Phillips, Edison’s Kinetoscope and Its Films: A History to 1896 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997).

[7] There is a voluminous literature on the concept and definition of the dispositif, embracing film, media, and communications studies as well as critical theory and philosophy. Important work includes Jean-Louis Baudry, “Cinéma: effets idéologiques produits par l’appareil de base,” Cinéthique 7–8 (1970): 1–8; Eng. ed. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic apparatus,” trans. Alan Williams, Film Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1974): 39–47, and his “Le dispositif: approches métapsychologiques de l’impression de réalité,” Communications 23 (1975): 56–72; Eng. ed. “The Apparatus,” Camera Obscura 1, no. 1 (1976): 104–26; Raymond Bellour, “La querelle des dispositifs / Battle of the Images,” Art Press 262 (2000): 48–52; Gilles Deleuze, “Qu’est-ce qu’un dispositif?,” in Michel Foucault. Philosophe: rencontre internationale, Paris, 9, 10, 11 janvier 1988 (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1989), 185–95; Eng. ed. “What is a dispositif ?,” in Michel Foucault Philosopher, trans. Timothy J. Armstrong (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992), 159–69; Michel Foucault, “The Confession of the Flesh,” a conversation with Alain Grosrichard et al., in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977 , ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 194–228; Jean-François Lyotard, Des dispositifs pulsionnels (Paris: Galilée, 1994); and Christian Metz, Le signifiant imaginaire: psychanalyse et cinéma (Paris: Union générale d’éditions, 1977); Eng. ed. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, trans. Celia Britton et al. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982). Davide Panagia offers a particularly useful account of the breadth of significance of the term as used by Foucault; see his article “On the Political Ontology of the Dispositif,” Critical Inquiry 45 (2019): 714–46. Specifically related to the topic of this article is Frank Kessler, “La cinématographie comme dispositif (du) spectaculaire,” CiNéMAS 14, no. 1 (2003): 21–34; and Kessler’s chapter “The Cinema of Attractions asDispositif,” in Strauven, Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, 57–69.

[8] Quoted in Gunning, “An Aesthetic of Astonishment,” 35.

[9] On the emergence of cinema as part of the modern urban experience, see Ben Singer, Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and its Contexts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001) and the essay collection Film 1900: Technology, Perception, Culture, ed. Annemone Ligensa and Klaus Kreimeier (New Barnet: John Libbey, 2009).

[10] See Laurent Guido, “Rhythmic Bodies/Movies: Dance as Attraction in Early Film Culture,” in Strauven, Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, 139–56; and Charles Musser, “At the Beginning: Motion Picture Production, Representation and Ideology at the Edison and Lumière Companies,” in The Silent Cinema Reader, ed. Lee Grieveson and Peter Krämer (London: Routledge, 2004), 15–30.

[11] From the wealth of recent interdisciplinary studies of attention, I have found the following most inspiring: Richard Adelman, Idleness and Aesthetic Consciousness, 1815–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Eve Tavor Bannet, Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading: Print Culture and Popular Instruction in the Anglophone Atlantic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017); Thomas H. Davenport and John C. Beck, The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001); Lily Gurton-Wachter, Watchwords: Romanticism and the Poetics of Attention (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016); and Tim Wu, The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016). Earlier studies that remain important include: Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999); Michael Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980); and James H. Johnson, Listening in Paris: A Cultural History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

[12] Dance scholar Stephanie Jordan offers a helpful review of music-dance research in her “Choreomusical Conversations: Facing a Double Challenge,” Dance Research Journal 43, no. 1 (2011): 43–64. Jordan’s own research—including the award-winning books Moving Music: Dialogues with Music in Twentieth-Century Ballet (London: Dance Books, 2000) and Stravinsky Dances: Re-Visions Across a Century (Alton: Dance Books, 2007)—illustrates the dominant methodological and conceptual tendencies of music and dance studies over the past twenty or so years. Having said this, her more recent work—for example, Mark Morris: Musician – Choreographer (Binsted: Dance Books, 2015)—treads new ground, exploring perspectives from the cognitive sciences.

[13] Gunning, “Cinema of Attractions,” 97–99.

[14] I attempted to tackle this last question in my chapter “Representational Conundrums: Music and Early Modern Dance,” in Representation in Western Music, ed. Joshua S. Walden (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 144–64.

[15] Carolyn Abbate, “Opera; or, the Envoicing of Women,” in Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship , ed. Ruth A. Solie (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 235

[16] See footnote 3 as well as André Gaudreault, From Plato to Lumière: Narration and Monstration in Literature and Cinema , trans. Timothy Barnard (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009); Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1990); his later article “Rethinking Early Cinema: Cinema of Attractions and Narrativity,” Yale Journal of Criticism 7, no. 2 (1994): 203–32; and Singer, Melodrama and Modernity.

[17] Louis Delluc, “Cinéma: Le Lys de la vie,” Paris-Midi, March 8, 1921.

[18] Louis and Auguste Lumière, Danse serpentine [II] (1897), Lumière Catalogue Number 765,1. See, also, the short films by Edison (Serpentine Dance, 1894) and Pathé ( Loie Fuller, 1905).

[19] There are two notable exceptions: Tom Gunning, “Light, Motion, Cinema!: The Heritage of Loïe Fuller and Germaine Dulac,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 46, no. 1 (2005): 106–29; and Felicia McCarren, Dancing Machines: Choreographies of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), esp. 43–64.

[20] Jacques Rancière, Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art, trans. Zakir Paul (London: Verso, 2013), 99. For historical sources, see Stéphane Mallarmé, “Considérations sur l’art du ballet et la Loïe Fuller,” National Observer, May 13, 1893 and Paul Valéry, “Philosophie de la danse” (1936), reprinted in Oeuvres, vol. 1, ed. Jean Hytier (Paris: Gallimard, 1957), pp. 1390–1403. Kristina Köhler offers a summary account of both Mallarmé and Valéry on dance in her chapter “Dance as Metaphor—Metaphor as Dance: Transfigurations of Dance in Culture and Aesthetics around 1900,” REAL Yearbook of Research in English and American Literature 25, no. 1 (2009): 163–78.

[21] Fuller, quoted in “Lois [sic] Fuller in a Church,” n.d.; clipping, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Theatre Collection Clippings 1. She continued: “No one can tell you what Beethoven thought when he wrote the Moonlight Sonata; no one knows Chopin’s point of view in his nocturnes, but to each music lover there is in them a story, the story of his own experience and his own explorations into the field of art … You can put as many stories as you wish to music, but you may be sure that no two people will see the same story. So every dance has its meaning, but your meaning is not mine, nor mine yours.”

[22] See my chapter “Making Moves in Reception Studies: Music, Listening and Loie Fuller,” in Musicology and Dance: Historical and Critical Perspectives , ed. Davinia Caddy and Maribeth Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 91–117.

[23] See Caddy, “Making Moves in Reception Studies” and, on the legal case, Anthea Kraut, “White Womanhood, Property Rights, and the Campaign for Choreographic Copyright: Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine Dance,” Dance Research Journal 43, no. 1 (2011): 2–26. Emma Doran provides an informative account of Fuller’s product branding—how she pioneered her own merchandizing, harnessing the press and the consumer industry to her advantage—in her article “Figuring Modern Dance within Fin-De-Siècle Visual Culture and Print: The Case of Loïe Fuller,” Early Popular Visual Culture 13, no. 1 (2015): 21–40.

[24] Gregory Shaya, “The Flâneur, the Badaud, and the Making of a Mass Public in France, circa 1860–1910,” American Historical Review 109, no. 1 (2004): 51.

[25] Tom Gunning, “The Whole Town’s Gawking: Early Cinema and the Visual Experience of Modernity,” Yale Journal of Criticism 7, no. 2 (1994): 190.

[26] For more on this, see Caddy, “Making Moves in Reception Studies.”

[27] Quoted in Martin Miller Marks, Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 251 n40. Marks notes that Loin du bal was included in the volume Masterpieces of Piano Music, ed. Albert E. Weir (New York: Carl Fischer, 1918), 365–67. For more on the Serpentine Dance, see Sally R. Sommer, “Loie Fuller’s Art of Music and Light,” Dance Chronicle 4, no. 4 (1981): 391.

[28] Addé, “Courrier des Spectacles: La Soirée au Théâtre des Arts,” Le Gaulois, November 10, 1907; Henri Gauthier-Villars, “Théâtre des Arts – La Musique,” Comoedia, November 10, 1907; see also Gaston Carraud, “Les Concerts,” La Liberté , November 12, 1907. Clair Rowden offers a useful account of the ballet in her chapter “Loïe Fuller et Salomé: les drames mimés de Gabriel Pierné et de Florent Schmitt,” in Musique et chorégraphie en France de Léo Delibes à Florent Schmitt , ed. Jean-Christophe Branger (Saint-Étienne: Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 2010), 215–59.

[29] See André Mangeot, “La Tragédie de Salomé,” Le Monde musical, November 15, 1907.

[30] Gauthier-Villars, “Théâtre des Arts,” 2.

[31] Interestingly, Fuller’s production was regarded as a feminist statement by both Le Temps, a daily newspaper, and the journal Fémina. Ann Cooper Albright discusses this aspect of the production, and Fuller’s earlier Salome outing (1895), in her book Traces of Light: Absence and Presence in the Work of Loïe Fuller (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), ch. 4 “Femininity with a Vengeance: Strategies of Veiling and Unveiling in Loïe Fuller’s Performances of Salomé,” 115–43.

[32] Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000).

[33] Marks, Skin of the Film, 167, 169.

[34] See, for example, Richard Taruskin, “Russian Folk Melodies in The Rite of Spring,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 33, no. 3 (1980): 501–43; Tatiana Baranova Monighetti, “Stravinsky, Roerich, and Old Slavic Rituals in The Rite of Spring,” in “The Rite of Spring” at 100, ed. Severine Neff, Maureen Carr, and Gretchen Horlacher (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 189–98; and Olga Haldey, Mamontov’s Private Opera: The Search for Modernism in Russian Theater (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

[35] I should also note the alternative perspectives offered during centennial celebrations by two expert musicological voices: Annegret Fauser, “Le Sacre du printemps: A Ballet for Paris,” and Tamara Levitz, “Racism at The Rite,” both in Neff et al., “The Rite of Spring” at 100 (83–97 and 146–78 respectively).

[36] Gunning, “The Cinema of Attractions,” 57. For more on this body of primary literature, see Viva Paci, “The Attraction of the Intelligent Eye: Obsessions with the Vision Machine in Early Film Theories,” in Strauven, Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, 121–37.

[37] See Tom Gunning, ‘“Now You See It, Now You Don’t’: The Temporality of the Cinema of Attractions,” Velvet Light Trap 32 (1993): 3–12.

[38] See Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through “Mavra” (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 2:1677–78. There is a sizeable music-theoretical literature on Stravinsky’s characteristic structural disjunctures, including Pieter C. van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983); Jonathan D. Kramer, “Discontinuity and Proportion in the Music of Stravinsky,” in Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist, ed. Jann Pasler (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 174–94; and Jonathan Cross, The Stravinsky Legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[39] John Frazer, Artificially Arranged Scenes: The Films of Georges Méliès (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979), 124.

[40] See Glenn Watkins, Pyramids at the Louvre: Music, Culture, and Collage from Stravinsky to the Postmodernists (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1994).

[41] Pierre Boulez, Stocktakings from an Apprenticeship, trans. Stephen Walsh (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 57.

[42] Linda M. Austin explores the trend towards marionettes and activated dolls in ballets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in her article ‘Elaborations of the Machine: The Automata Ballets’, Modernism/modernity, 23/1 (2016), pp. 65–87. On dance’s centrality to modernist machine aesthetics, see McCarren, Dancing Machines.

[43] Truman Bullard collates and translates all extant reviews of Le Sacre (dating from the months after the premiere) in his doctoral thesis “The First Performance of Igor Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, Eastman School of Music, 1971), from which this article’s English translations are taken, unless otherwise noted. See, in particular, Gustave de Pawlowski, “Au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées: Le Sacre du Printemps,” Comoedia, May 31, 1913.

[44] “The Next New Russian Ballet,” interview with Vaslav Nijinsky, Pall Mall Gazette, February 15, 1913, 5.

[45] See, for example, Jordan, Moving Music, 36–42; Millicent Hodson, Nijinsky’s Crime Against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps” (Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press, 1996); and Hodson and Kenneth Archer, The Lost Rite: Rediscovery of the 1913 “Rite of Spring” (London: KMS Press, 2014).

[46] My admittedly crude account of the prehistory of counting is heavily influenced by the work of James Elkins: “On the Impossibility of Close Reading: The Case of Alexander Marshack,” Current Anthropology 37, no. 2 (1996): 185–226, and his book On Pictures and the Words That Fail Them (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), esp. ch. 5 “The Common Origins of Pictures, Writing, and Notation.” Elkins himself, as the title of the above article makes clear, draws on the writings of archaeologist and art historian Alexander Marshack, especially his The Roots of Civilization: The Cognitive Beginnings of Man’s First Art, Symbol, and Notation (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971, and on Denise Schmandt-Besserat,Before Writing, vol. 1, From Counting to Cuneiform (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992).

[47] See The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, ed. Joan Ross Acocella, unexpurgated ed. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999), xiii; and Mindy Aloff, Dance Anecdotes: Stories from the Worlds of Ballet, Broadway, the Ballroom, and Modern Dance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 15.

[48] Stravinsky commented on this disparity in his notes to the four-hand piano version of Le Sacre; see Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, “The Rite of Spring”: Sketches 1911–1913 (London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1969), Appendix III, 38–39.

[49] See, for example, Juliet Bellow, Modernism on Stage: The Ballets Russes and the Parisian Avant-Garde (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), esp. 57.

[50] For more on the earliest technologies of sound inscription, see Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); and Haun Saussy, The Ethnography of Rhythm: Orality and Its Technologies (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016).

[51] See Friedrich A. Kittler, Discourse Networks 1800/1900, trans. Michael Metteer (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), and Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999); and Sara Danius, The Senses of Modernism: Technology, Perception, and Aesthetics (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002).

[52] See Steven Connor, “The Modern Auditory I,” in Rewriting the Self: Histories from the Renaissance to the Present , ed. Roy Porter (London: Routledge, 1997), 203–23. I have also enjoyed (on literature) Angela Frattarola, “Developing an Ear for the Modernist Novel: Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, and James Joyce,” Journal of Modern Literature 33, no. 1 (2009): 132–53; and (on aurality more broadly) Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

[53] Connor, “The Modern Auditory I,” 207.

[54] Connor, 204.

[55] Pierre Lalo, “La Musique,” Le Temps, June 3, 1913, 3.

[56] Lalo, 3. As Bullard notes, Lalo’s review offers a particularly severe criticism of Nijinsky (and his “lack of choreographic imagination”), while remaining deferential to Stravinsky (“a prodigiously ingenious and skillful composer”). See Bullard, “The First Performance,” 2:85. For a careful and thorough account of critics’ reviews, see Sarah Gutsche-Miller, “What the Papers Say,” in The Cambridge Companion to “The Rite of Spring,” ed. Davinia Caddy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

[57] See, for example, Gustave Linor, “Au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées: Le Sacre du Printemps,” Comoedia, May 30, 1913; and Marguerite Casalonga, “Nijinsky et Le Sacre du Printemps,” Comoedia illustré, June 5, 1913.

[58] See, for example, Louis Vuillemin, “Au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées: Le Sacre du Printemps. Ballet en deux actes, de M. Igor Stravinsky ,” Comoedia, May 31, 1913; Georges Pioch, “Les Premières. Théâtre des Champs-Elysées: Le Sacre du Printemps,” Gil Blas, May 30, 1913; and Pierre Lalo, “La musique.” As Bullard notes, only the most hostile critics—Adolphe Boschot, Paul Souday, Henri de Curzon, and Adolphe Jullien—wrote with any degree of self-assurance; see Bullard, “The First Performance,” 1:166–67.

[59] Jacques-Émile Blanche, writing an annual overview of theatrical life in the French capital, admits that “I hesitated a long time before I dared to take Le Sacre du Printemps as the principal subject of these remarks.” He goes on to acknowledge that, following the 1913 Russian season, “it has taken us a little while to regain our aplomb”; see his article “Un bilan artistique de 1913. Les russes—Le Sacre du Printemps,” La revue de Paris, December 1, 1913 (Bullard, 2:313–14).

[60] See the January–February 1914 edition of the short-lived journal Montjoie!, including editor Ricciotto Canudo’s “Manifeste de l’art cérébriste,” 9.

[61] Xavier Leroux, “La saison russe,” Musica 12, no. 131 (August 1913), 153 (Bullard, 2:214).

[62] See René Chalupt, “Le mois du musicien,” La Phalange 8 (August 20, 1913): 169–75 (Bullard, 224–30); and Jean Marnold, “Musique,” Mercure de France 24, no. 391 (October 1, 1913): 623–30 (Bullard, 250–68).

[63] Jacques Rivière, “Le Sacre du Printemps,” La Nouvelle revue française 5, no. 59 (November 1, 1913): 706–30 (Bullard, 280).

[64] Bullard, 298.

[65] Marks, The Skin of the Film, 1.

[66] Marks, 168.

[67] Marks, 167, 169.

[68] Marks, 170.

[69] Marks, 170–71.

[70] See Penelope Murray and Peter Wilson, eds., Music and the Muses: The Culture of “Mousikē” in the Classical Athenian City (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); and Barbara Kowalzig and Peter Wilson, eds., Dithyramb in Context (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[71] For more on the traditional bonisseur, see Germain Lacasse, “The Lecturer and the Attraction,” in Strauven, Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, 181–91.

[72] See Theodor W. Adorno, Philosophy of New Music (1949), trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 111; see also Richard Taruskin, “A Myth of the Twentieth Century: The Rite of Spring, the Tradition of the New, and ‘The Music Itself,’” Modernism/Modernity 2, no. 1 (1995): 1–26.

[73] Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 1:962.

[74] See Tamara Levitz, “The Chosen One’s Choice,” in Beyond Structural Listening? Postmodern Modes of Hearing, ed. Andrew Dell’Antonio (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 70–108.

[75] See Fried, Absorption and Theatricality, and his essay “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum 5, no. 10 (1967): 12–23.