Increasing Public Participation in Local Government by Means of Mobile Phones: the View of South African Youth

Centre for IT and National Development in Africa, Department of Information Systems, University of Cape Town, South Africa

- Professor, Department of Information Systems, University of Cape Town, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

- Honours student, Department of Information Systems, University of Cape Town, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

1. INTRODUCTION

There is a general apathy towards political participation worldwide, even in developed countries such as Switzerland and the United Kingdom (UK), which show a decline in voter turnout over the last few decades (Brücher & Baumberger, 2003). Governments around the world have introduced initiatives to include citizens in the decision-making process. Although most citizens, only interact with government during elections, there are many ways in which citizens can participate on an on-going basis (Pahad, 2005). Public participation is necessary to ensure that citizens are able to influence the decision-makers in government, especially in situations where the decisions taken affect their lives directly (Creighton, 2005). It is at the local level where citizens experience the direct effect of political decisions.

Decentralising and encouraging more citizen participation requires adequate mechanisms for engagement. The constitution of South Africa has been hailed by many as the most progressive in the world, and makes specific provision for public participation. Section 152 of the Constitution speaks of democracy, accountability, and the encouragement of involvement in matters of local government. Section 16(1) of the Local Government Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000, echoes this need for, and encouragement of participation in local matters, and adds that local government should do whatever it can to facilitate this process (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, 2009).

Mobile phones are usually used as communication tools, but they have also been used by ordinary people to mobilise others, who were previously passive, into political action. This indicates that there are drivers or motivators that bring about political participation, other than just the use of technology. What has eluded governments is how to fully utilise the capabilities of mobile phones to reach almost every citizen, and in so doing possibly reverse the increasing political apathy amongst their citizens (Hermanns, 2008).

While the potential of mobile to transform government interaction with citizens is widely acknowledged, the use of existing mobile government services is not widespread (Bagui, Sigwejo, & Bytheway, 2011; Chigona, Beukes, Vally, & Tanner, 2009). The objective of this research, therefore, is to investigate what youth think about interacting with government via their mobile phone. More specifically, this research aims to answer the following questions:

- What are the key factors influencing the intention to use mobile phones as a medium for public participation?

- What types and levels of participation are most desired by those surveyed: informational (G2C), polls/voting, feedback/commentary (C2G) or citizen contact (C2C)?

- What areas of concern do youth have in respect of using mobiles in the participation process, as for example security or cost?

The focus of this research is on local government participation, since the local arena is seen as of more immediate concern to respondents, although a few questions related to engagement with national government.

This research thus hopes to add to the understanding of youth perceptions towards political participation using mobile phones, and reveals some of the inhibitors to participation while exploring interest in specific mobile government services.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Democracy and Participation

Participatory democracy models are based on the belief "that the very act of involvement is beneficial in that it permits all citizens, and not merely elites, to acquire a democratic political culture" (Deegan, 2002, p. 45). Participation is an important part of any modern democracy, even though many citizens perceive that their only influence over government lies in their ability to occasionally cast their vote (Creighton, 2005). Not allowing for participation limits a government's sources of options and ideas, and also exposes the process to corruption, which (it is argued) would be addressed through public scrutiny if citizens were more involved (Creighton, 2005).

The reasons for low participation vary from the simplistic--people would rather spend their time doing something else, to issues of practicality, and principle (Brücher & Baumberger, 2003). In some cases politics can be difficult to understand and therefore can be a barrier to participation. Many people do not know how to communicate their wishes correctly, or how to use the available mechanisms for participation appropriately. Public participation should not just be viewed as events, such as elections, protests or demonstrations, but rather as an on-going, and evolving process that requires as much a change in public perception and mind set, as a government commitment to explore new systems of participation.

According to (Mattes, 2002), South Africans are passive when it comes to community involvement. In a study including over 2,200 respondents, only 4 indicated that they had made any attempts to, "attend any hearing or meeting organised by Parliament or by an MP" (Mattes, 2002, p. 33). There is therefore a need for other approaches to not only monitor participatory processes, such as the status of requests made to local councillors, but also new ways in which to disseminate information (Nyalunga, 2006). The ability to track what Ccouncillors are doing between elections, is important for both citizens and government, and could not only improve accountability, which is stipulated in Section 152 of the Constitution, but also provide citizens with valuable information which could help them evaluate their local Ccouncillor in the run-up to local elections.

2.2 E-Government and M-Government

Governments around the world have embraced the Internet and the world-wide-web to deliver e-government services to citizens (Yildiz, 2007). E-government, in its broad sense, is the use of information technology to enable or enhance government processes, of which the use of the Internet is only one part (Grant, Hackney, & Edgar, 2010).

In South Africa, as in many developing countries, traditional e-government can be said to widen the gap between "haves" and "have-nots", since the poor and disenfranchised typically have no access to fixed Internet. However, m-government entails the distribution of government services utilising mobile technologies (Carroll, 2005). The potential of m-government, enabled by ubiquitous mobile phones, is to provide services, especially to previously disadvantaged groups, as well as to provide a new mechanism for public participation in politics (Poblet, 2011). However, this requires the creation of applications that leverage the appropriate mobile technology to create useful government services (Patel & White, 2005; Poblet, 2011). The innovation here is taking advantage of "the most basic capacities of already existing technologies to reach broader population segments which otherwise would not have had access to more costly and sophisticated mobile technologies" (Poblet, 2011, p. 503).

The widespread availability of mobile phones (Trimi & Sheng, 2008) has seen them being used in applications ranging from reality television voting, to crime fighting, banking, commerce applications, enabling easy donations to charity, the supply of various kinds of information, among other areas (Patel & White, 2005). Traditionally, citizens who want to engage in dialogue with government such as for gaining information, discussions, public hearings, o voting, are required to be physically present (Brücher & Baumberger, 2003). This in itself poses practical problems for many, such as inconvenient times or locality. This is highlighted by Patel and White (2005) who in their review of government call centres cite as reasons for their failure, such call cost, limitations on 'open' hours, and insufficient resources. They also cite the problems of queues, which could translate into loss of income for citizens, compared with direct government enquiries or information centres, as points of contact. This highlights the need for governments to explore different ways to interface with citizens, not only in the provision of information, but also to engage in dialogue.

Many services are procedural or bureaucratic in nature, such as notifications of status changes in identity document requests, or the confirmation of actions. Vincent and Harris (2008) cite examples in Lewisham, and Hillingdon, in the United Kingdom (UK) where mobile text services relay information such as employment opportunities, events, and "food safety warnings". Citizens are allowed to upload photographs of problems such as potholes, request garbage removal, or to report broken lights.

Mobile phone users already engage in a wide range of participatory activities such as reporting traffic congestion, entering competitions, taking and distributing photographs, or spreading news of different events (Vincent & Harris, 2008). Mobile phones have contributed to greater awareness and interest in politics, and have proven to be an effective tool in facilitating information sharing between "a large number of similarly minded people within a short period of time and at short notice (Hermanns, 2008, p. 79). Mobile phones have definitely created new ways in which citizens can participate, and can deliver applications that address the need for "innovative ways of popular participation" (Nyalunga, 2006, p. 5).

The current position of mobile phones as a platform to encourage participation is without question, but there are concerns around personal privacy and security if this platform were to be used to report on corruption, or criticise government (Poblet, 2011). However, South Africa has some experience in this regard with its award-winning 32211 SMS tip-off crimeline (SAinfo , 2010). In this case anonymity is guaranteed, not by government or the police, but by private enterprises. The initiative was spearheaded and is supported by private enterprise, and possibly this 'buffer' to government gives citizens the necessary 'comfort' to freely express their opinion. The promise that personal information will not be passed on to the authorities has been enough for citizens, and since its launch in 2007, the crimeline has resulted in over 1000 arrests, as well as the seizure of over R36 millon in stolen property (SAinfo , 2010).

E-Participation and m-Participation can thus be conceptualized as extensions of e-Government and m-Government respectively. However, it is important to define these concepts more accurately in order to operationalize them for empirical research purposes.

2.3 E-Participation and M-Participation

An extensive literature of more than one hundred relevant academic articles (Rose & Sanford, 2007) revealed that no consensus had been reached on a precise definition of e-Participation (also referred to as eParticipation) but found it described operationally as "technology-facilitated citizen participation in (democratic) deliberation and decision-making". A slightly more detailed definition explicitly includes the aspects of Citizen to Government (C2G), Government to Citizen (G2C) and Citizen to Citizen (C2C): "eParticipation refers to efforts to broaden and deepen political participation by enabling citizens to connect with one another, with civil servants, and with elected representatives using ICTs" (O'Donnell et al, 2007). A more process-oriented definition of e-Participation is "ICT-supported participation in processes involved in government and governance. Processes may concern administration, service delivery, decision-making and policy making." (Macintosh & Whyte, 2006, 2008). This is a refinement of their earlier definition which focussed on only the participation in the early decision-making and e-voting processes (Macintosh, 2004).

However, it is important not to take a purely technicist approach to e-Participation i.e. focus solely on the technology or process aspects. The underlying motivations and wider socio-political dimensions are very important in understanding the diffusion and adoption of e-Participation, motivating academic studies requiring ethnographic and other interpretive research approaches focussing on one or a very few actual projects (Ekelin, 2007).

In all of the above definitions, m-Participation can be equivalently defined by the use of mobile information and communication technologies. Although these would typically include mobile notebook computers, personal digital assistants and tablet computers in the context of m-Government, especially in a G2G context, where citizens are involved, m-Participation will often focus on the use of mobile phones.

The European Union has strongly supported a number of e-Participation initiatives and, by 2008, already more than 35 such EU-sponsored initiatives were underway, both at the national and local levels (Tambouris, Kalampokis and Tarabanis, 2008). However, assessing the success and impact of e-Participation initiatives is not straightforward (Tambouris, Liotas & Tarabanis, 2007). A later and more comprehensive survey on e-Participation initiatives identified 255 e-Participation initiatives across the European Union (Panopoulou, Tambouris & Tarabanis, 2009). Interestingly, the type of participation appeared to be mainly about information provision (in 111 out of 255 projects); deliberation (77), consultation (72) and discourse (40). Only a small number was concerned with campaigning and petitioning (28), community building (28), polling (26), voting (10) or mediation (Panopoulou et al, 2009).

Given the above definitions, m-Participation has been operationalised in this research to include the following specific and concrete C2G/G2C interactions: communicating with community members and local councillors; influencing politicians; polling and voting on community issues, local and national elections; reporting community problems; getting information from government; complaining about service delivery; reporting corruption; interacting with (national) departments such as Labour, Housing and Home Affairs).

Although quite a bit of research has been done on m-Government in Africa, not many studies have been conducted in Africa (or South Africa) on m-Participation. A notable exception is a recent comparative assessment of m-Participation in Tanzania and South Africa (Bagui, Sigwejo & Bytheway, 2011). This exploratory study interviewed key actors involved with a case study in Cape Town and compared the context with the situation in Tanzania.

2.4 Participating at Local Versus National Level

M-participation can happen at the local, provincial (or regional) and national government levels.

It is sometimes assumed that it is easier to raise awareness and rally support around local issues than for national issues (Ekelin, 2007). However, many of the early m-Participation projects were aimed at participation at the regional or national level. For instance, in the survey of 255 European M-participation projects,less than one third, namely 80 (31%) were at the local level; 43 (17%) of the projects were at the regional level; 72 (28%) at the national level; and the remainder at the supra-national level (Panopoulou, Tambouris & Tarabanis, 2009). Also interesting is that the type or nature of projects did not differ significantly between local, regional or national initiatives. However, it must be borne in mind that many of these initiatives were in countries that are substantially smaller than South Africa.

The South African historical context and current situation seems to favour a route whereby participation in local government decision-making may be a first step along the route to full m-participation. Prior to 1996, local government had little autonomy, and decisions were subject to judicial review by provincial and national governments. A new view of an autonomous local government was further enshrined in the Constitution and local government could govern as they saw fit, with National and Provincial government playing more of an 'overseeing' role. At the local level, the challenges for previously disadvantaged areas remain deeply rooted in the racially divided past with the lack of adequate infrastructure limiting the delivery of services and supply of resources. Local government was not only enabled with both fiscal and legislative powers in order to improve service delivery at the local level, but as they were also at the 'coal face', they were seen as best suited to deliver these services in consultation with, and through active participation by citizens (SALGA, 2013)

Local government participation mechanisms such as Ward Committees have unfortunately been plagued with problems due to scarce resources, power struggles between ward councillors and ward committee members, as well as a lack of clearly defined roles. Effective channels for citizen participation at a local government level are not prevalent, in part due to a lack of trust between the different stakeholders, and/or the lack of representation of various stakeholders within community structures. This lack of representation can be seen in the exclusion of Civil Society Organisations who could play a crucial role as 'observers' and 'monitors' at the local level. Party politicization of community participation and ward committees also present barriers to those who are non-partisan, and the outcome of ineffective participation processes is also witnessed in outbreaks of countrywide protests (Nyalunga, 2006).

The observation that public participation at the local level has largely proven to be unsuccessful is supported by others such as Williams (2006, p. 197) who states that citizens have unfortunately merely become "endorsees of predefined planning programmes". In this research, therefore, the focus was mainly on intentions to participate in local government, although a few questions also related to participation at the national government level (as noted in the abbreviated survey instrument in the Appendix).

2.5 Theoretical Framework

In order to determine the key factors that influence m-Participation intentions, a theoretical framework is required. Although admittedly m-Participation cannot be seen as a purely technological issue, this research does take an information systems approach and thus looked at technology adoption models. Technology adoption models are typically used to determine the levels of intention to use and acceptance of new technology (Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003), including m-Commerce, m-Government and Unified Communications.

Venkatesh et al. (2003) consolidated different acceptance models into the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). This model incorporates elements of the Theory of Reasoned Action, the Theory of Planned Behaviour, the Technology Acceptance Model, the Motivational Model, the Model of PC Utilisation, the Innovation of Diffusion Theory, and the Social Cognitive Theory, which all previously had been used to determine IT acceptance. The UTAUT model is chosen for this study because it has been shown to be more accurate as a predictor of acceptance and adoption than any of the other adoption models used in isolation (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In our original research, an effort was made to include variables from a 'non-technicist' model, namely social capital theory, but none of the theory's variables were found to exert a significant effect. Thus this model has been not been incorporated into this paper.

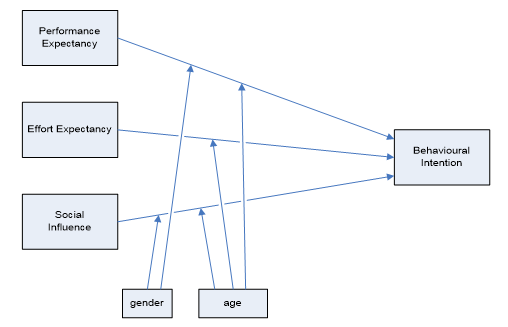

Since this research investigates the perceptions of, and behavioural intention (BI) to use mobile phones to interact with government, some parts of the UTAUT model were not considered. Figure 1 shows the modified model which was used in this research. Both "use behaviour" and "experience" are excluded as there is no widespread availability of government mobile services, and therefore use of or experience with mobile phone government services in South Africa. In the context of this research, the use of mobile phones to interact with government would be voluntary, so the voluntariness of use as a moderator is also excluded. Facilitating conditions was also removed as it affects UB which was removed, but not BI. The Social Influence (SI) construct has been shown to have a notable effect on BI. However, the moderating constructs of SI, are only significant in environments where use is not voluntary (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This section details the research methodology used for achieving the research objectives.

3.1 Research Objectives and Hypotheses

The objective of this research is to investigate what youth think about interacting with government via their mobile phone. More specifically:

- To determine the factors influencing the intention to use mobile phones as a medium to engage in public participation.

- To establish what level of participation would be desired : informational (G2C), polls/voting, feedback/commentary (C2G) and/or citizen contact (C2C)

- To identify areas of concern in the use of mobiles in the participation process, such as security and cost.

The following hypotheses, related to the first research objective, are directly adapted from the UTAUT model:

H1: Performance expectancy (PE) will have a positive influence on the behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation. This influence is moderated by gender and age (stronger influence for men and younger users).

H2: Effort expectancy (EE) will have a positive influence on behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation. This influence is stronger for women than men.

H3: Social influence (SI) will have a positive influence on behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation. This influence is moderated by gender and age.

These hypotheses will be tested quantiatively in section 4 using inferential statistical methods.

The second and third research objectives are explored both quantatively and qualitatively in section 5 using a combination of descriptive statistics and relevant quotes from interviews.

3.2 Research Philosophy, Sampling Approach and Instrument

The underlying philosophy for this research is positivist as it attempts to determine what drives the use of mobile phones in political participation partly by validating the hypotheses of the UTAUT model. The research strategy employed a survey to capture data for quantitative analysis, and semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data. The analysis of the qualitative data offers improved clarity on some of the relationships found during the quantitative data analysis. The research is also cross-sectional as data was collected over a period of four weeks beginning in the first week of July 2011.

The target population consisted of individuals between the ages of 18 and 35, who did not have access to fixed-line Internet either from home or work. Those who had infrequent access to fixed-line Internet via facilities such as public libraries were allowed to participate in the survey. A convenience sampling approach was adopted, because of the ease of access to potential participants.

The survey instrument included demographic questions, test items from the UTAUT model to measure intention to use technology, individual perceptions of politics, as well as some elements of social capital theory. Most questions adopted a 5-point Likert answer scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. To be as inclusive as possible, the English instrument was translated into Afrikaans and Xhosa and Xhosa-speaking facilitators were used in the interviews. The complete questionnaires are available from the authors on request but salient questions are included in the Appendix.

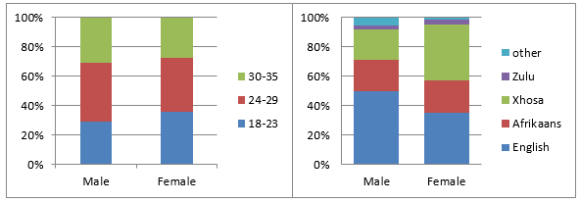

The data was collected in factories, churches, taxi ranks, a fast food outlet, and office buildings. Survey respondents were not asked where they lived, and data was collected from a variety of areas, including the Cape Town city centre, Khayelitsha, Westlake, Claremont, Hanover Park, Belhar, Charlesville and Retreat. A total of 131 usable questionnaires were available for data analysis. Respondents had mobile phones, all but two being Java enabled, and all but one Internet-enabled, confirming the trend towards smart phones. Although home language was captured and is referred to, it is in no way implied that it is a proxy for race. Figure 2 shows the demographics of the respondents by age and language.

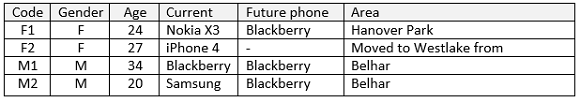

Four people (two of each gender) were also interviewed in order to gather additional qualitative insights. The semi-structured interview protocol contained open-ended questions to encourage subjective opinions, and prompting by the researcher also allowed for a more conversational process (see Appendix). When mentioned in the analysis, participant citing for the interview respondents is as per Table 1.

As shown below, most of the comments made during the interviews confirmed the findings from the survey and supported the majority views. Thus the quotes given below are generally added to give 'colour' to the survey data.

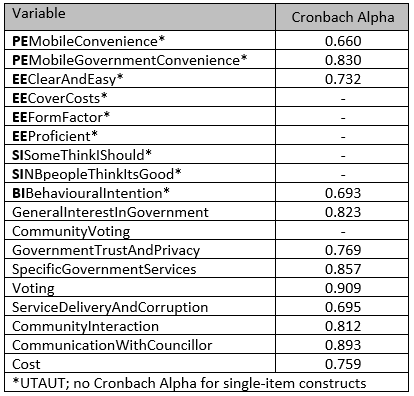

4. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE USE OF MOBILE PHONES FOR POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

The modified UTUAT model was used to determine the behavioural intention to use a mobile phone to interact with government. Performance Expectancy (EE) was broken down into two constructs: (General) Convenience and Convenience specifically for M-Government of Mobile Technologies. Effort Expectancy consisted of 4 constructs: Clear & Easy to Use, Costs, Device Form Factors and User Proficiency. Like PE, Social Influence (SI) was broken down into a more generic construct relating to "Some people I know" and one referring specifically to people important to the respondent. All Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficients for the multiple test items were in the range 0.66-0.83. The reliability coefficients for the model constructs as well as other variables used elsewhere in the research are shown in Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis was used to determine the degree of influence the new variables have over BI. Some of the PE and EE variables are significantly related to BI, as explained in the analysis below. The variables used in the multiple regression account for 46.5% (r2 = 0.465) of the variance in the intention to use mobile phones to interact with government.

H1: Performance expectancy will have a positive influence on the behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation.

The multiple regression analysis shows a highly significant and positive (p = 0.007, beta = 0.260) relationship between the variables PEGovernmentMobileConvenience and Behavioural Intention. There is therefore strong evidence against the null hypothesis and it is therefore rejected. However, neither age category nor gender, were found to have a moderating influence.

H2: Effort expectancy will have a positive influence on behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation.

The multiple regression analysis supports an extremely significant and positive (p < .000, beta = 0.375) relationship between the variable EEProficient and Behavioural Intention. This is strong evidence against the null hypothesis, and the result supports the hypothesis that effort expectancy is a predictor for behavioural intention. Over 67% of respondents indicated that they expected that they would become very good at using their mobile phone to interact with government. Tests reveal no statistical significance in the relationship between effort expectancy and behavioural intention when gender is used as a moderator.

H3: Social influence will have a positive influence on behavioural intention to use mobile phones as a medium for political participation.

The multiple regression analysis finds no statistically significant relationship between any of the SI variables and Behavioural Intention. Because of this, it was not necessary to test the moderating impacts of gender or age.

The drivers of Behavioural Intention in the modified UTAUT model include PE and EE factors, both exhibiting positive and significant relationships with BI. That social influence has no effect on behavioural intention was expected, as social influence has only been shown to have an effect within non-voluntary environments.

From this it can be concluded that the respondents perceive government mobile services to be useful and would add value to their lives. They also have the perception that not only would these services be easy to use but that they would also easily become proficient in using them. It can be concluded that the expectation is that the user interface of government mobile application or services would be very user friendly. Failure to meet this expectation would affect the behavioural intention and ultimately the use of the services or applications.

5. TYPES AND LEVELS OF M-PARTICIPATION

5.1 General Interest in Politics and Participation

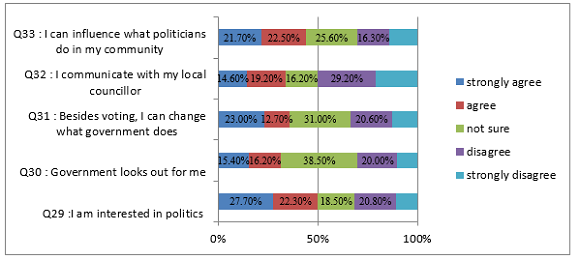

Although there was some interest in politics, it appears that citizens did not believe they could change what government does. Only 35.7% (strongly agree = 23.0%, agree = 12.7%) indicated that besides voting, they could influence what government does. Another 31% were not sure, while 33% (disagree = 20.6%, strongly disagree= 12.7%) did not believe they could make a difference (Figure 3).

Some citizens felt that they could have marginally more influence at the local level. When asked whether they felt they could influence what politicians do in their community, 25.6% were not sure. However, with 44.2% who were in agreement (strongly agree = 21.7%, agree = 22.5 %), 25.6% not sure, and 33.3% who responded negatively, it appears that there was no consensus on having an influence over community politics.

This feeling of 'disempowerment' was reflected by the interviewees: "I'm a youth I don't have time for this. What can I do... nothing" (F1). "I don't watch a lot of news. I don't know a lot about uhm, politics" (M2). "I take a slight interest in…what gets done in the country, in the level of crime, uhm visible police - how often you see them and how many of them you do. But I don't take an interest in the sense where I will complain about certain things they don't do, or the things I don't see. I'm very, a complacent person, I'm very happy with the way I am and how things are. I'll just live with it instead of complaining" (M2).

Moreover, interest does not always translate into action. The literature mentions that there may be many different reasons why people do not interact with government, some practical, others personal. That people do not feel that they can make a difference is one of them. Those who were not sure whether government looks out for them amounted to 38.5%., with 31.6% who did think that government looks out for them. One interviewee cited politician self-interest as taking priority over serving the people: "They talk too much about themselves and not about the real issues. When they showed a debate on special assignment or third degree it shows what really goes on." (F1)

Despite this, interest in voting on community issues was positive (Strongly agree = 34.4%, agree = 31.3%, Mean = 2.2). In the context of SCT the results indicated low linking capital, or connection between citizens and government. This disconnect is further supported by looking at citizen trust in government.

In summary, there appears to be a measure of interest in politics with a greater tendency towards community politics. However the citizen perception of a 'divide' between themselves and government would have to be bridged to build a trusting relationship. As mentioned in the literature, mobile phones can help build social capital by enabling citizens to 'link' to government more easily, as well as providing mechanisms to monitor service delivery.

5.2 Mobile Phones as a Convenient Means of Interaction

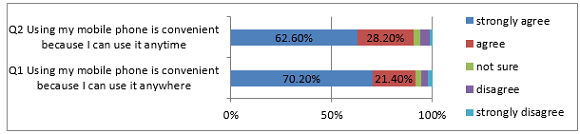

Convenience could be a major factor affecting the adoption of mobile Internet (Chigona etal., 2009). Some test items indicated the degree to which mobile phones were seen as a convenient means of interaction, both in general and more specifically for government interaction (Figure 4).

A positive (strongly agree = 70.2%, agree = 21.4%) response was received to the perception that mobiles were convenient because they could be used anywhere. There was also agreement (strongly agree = 62.6%, agree = 28.2%) that the anytime nature of mobiles contributed to this convenience.

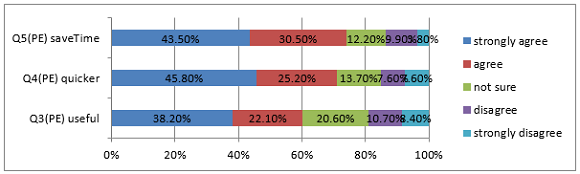

74% of respondents agreed (43.5% strongly) that using mobile phones to interact with government would save time, and 71% agreed (46% strongly) that using a mobile phone to get information would be quicker than visiting government offices (Figure 5). All interviewees agreed that it would be more convenient, saving both time and money: "It would be convenient for me, and save me time and trouble" (F1); "less time consuming, saving you a lot of effort, maybe to drive to Home Affairs" (M2). 60% also indicated that they believed it would be useful to communicate with government using a mobile phone.

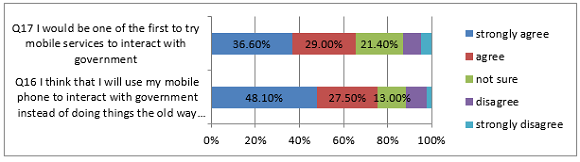

However, interestingly, there was slightly higher support when asked about the Intention to use the mobile phone to interact with the government. The response was favourable with 65.6% (strongly agree = 36.6%, agree = 29%) indicating that they would be one of the first to try mobile services to interact with government (Figure 6).

Some explanation for this positive intention to use government mobile services could be as a reaction to issues experienced when dealing with government departments by the means that are currently available: "it's a hassle..in all of them" (F2); "lines are long and it takes a bit of time" (M2); "if you have a problem, a need to go to Home Affairs, you need to find out something, you have to take off work" (M1); "At SARS [South African Revenue Services] there are these moerse [i.e. very] long lines. This one person had the same ID as my mom and she had to pay extra tax. It took 3 days. There were very long lines" (F1).

Time and cost were recurring areas of concern for the demographic who were included in this research. For many, a day off work to visit government offices means no pay, as well as travel and other costs. The interest in, and the appeal of mobile services, is that they could potentially save them time and money. So the eagerness expressed to use the services when they become available is understandable.

In summary, it is evident that mobile phones have become a part of many people's everyday lives and its convenience is reflected in the highly positive responses to questions around its use anywhere and anytime. Overall there was also a very positive perception that mobile government services would not only save time and be quicker, but would also be useful, which bodes well for the introduction of government mobile services.

5.3 Levels of Participation

5.3.1 Receiving Information via a Mobile Phone

As mentioned towards the end of the last section, the methods of interacting with government services has both time and financial implications for citizens. In the literature, Patel and White (2005), cite problems in government call centres, and enquiry or information centres and services. The time and money saved through the use of mobile Internet was also reported by Chigona et al. (2009).

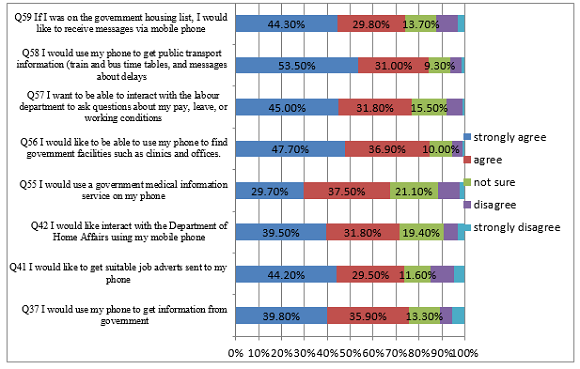

Figure 7 details the respondents' level of interest in the different types of mobile services and participation types.

Participants responded positively (strongly agree = 39.8%, agree = 35.9%) to the general statement about using their mobile phone to get information from government departments. For most South Africans, there is a great dependence on public transport, and this is linked to their livelihood. There was an overwhelming 80%, both receiving public transport information, and finding government offices and clinics, who showed interest in using mobile phones as a medium of interaction.

In other cases, information could be 'pushed' to citizens, such as in the example cited in the literature on the broadcast of 'food safety warnings' in the UK. There are also notification services where citizens are informed of the status of their requests, which are triggered by an event such as an application for a new identity document.

Citizens could request information on an ad-hoc basis depending on their needs, such as the location of the closest Labour Department office. The responses about the need to have interaction with the Labour Department were very positive at 76.8% (strongly agree = 45%, agree = 31.8%) and the need for these services was supported by the suggestion of such a service by one of the interview participants: "if there's a department of labour in Wynberg and stuff like that. If I need to know where to find which offices…nearest to my community" (F2)

There were also positive responses to the other questions on receiving messages in other situations, for example if a person was on the housing list, for medical information, as well as concerning job vacancies.

5.2.2 Voting

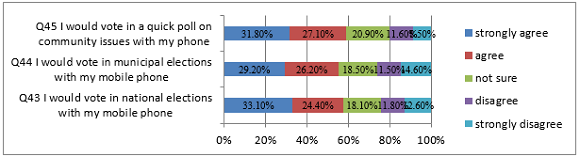

When asked about voting, respondents indicated that they would be interested. Quick polls on community issues featured strongly with 58.9% (strongly agree = 31.8%, agree = 27.1%, Mean = 2.24), and were very closely followed by voting in national and municipal elections (Figure 8).

Although platforms for voting exist, Hermanns (2008) warns against equating voting in a political election, to voting on a reality television show. This warning finds traction in the following statement: "you can vote for your Idol on MxiT [a hugely popular South African Mobile Instant Messaging platform]….There's so many other things on MxIT, so why not vote things in your community on MxIt" (M2). Literature also suggests that making electronic voting available may in fact, not increase voter turnout, and Vincent and Harris (2008) stated that it is more likely to be used by existing voters.

5.2.3 Reporting Service Delivery, Corruption and Community Problems

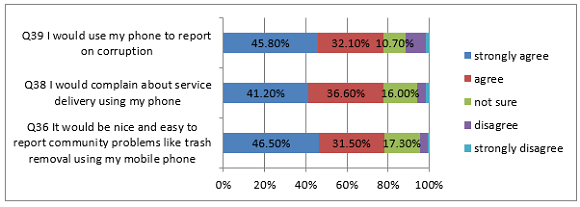

Writing letters, sending SMSs or attending public meetings are some of the ways in which citizens can express their views. The few that do have access to the Internet, could post comments onto websites, or write blogs. Figure 9 details some of the ways respondents would like to use their mobile phones to respond to service delivery issues or report corruption.

Service delivery issues could be approached from a more positive and proactive perspective, where posts would serve to inform rather than to apportion blame: "[it] would be a good idea to use a cell phone, so that they can be informed and also know on their services where they can maybe, they can pick up...improve on their services" (M1)

Respondents, when asked if they would like to report community problems such as the lack of trash removal, using their mobile phone, responded positively (78%) which was an indication that a service with features such as those in SeeClickFix would be a good starting point.

Reporting also raises the issue of anonymity. Interviewees gave mixed responses when asked whether they would rather be anonymous when reporting: "I don't mind really...to give my name. Ja, its, I don't mind giving my name" (M1) as opposed to "rather remain anonymous, …but at some times ..I don't think it would be a big thing…for them to know who it is" (M2). Probing a bit deeper, M2 was asked whether he would feel differently if what he was reporting was a bit closer to home, such as reporting his local councillor for a lack of service delivery, or corruption: "it could be a bit...intimidating just knowing that...they know it's me, should I, or shouldn't I. It will leave a big question, but if it's a big enough thing and like you have an actual reason for doing then I guess it all depends on the type of person you are and how confident you are" (M2)

With nearly 80% in agreement, a service that would allow for reporting corruption, service delivery and community problems would be well received. It is only natural for people to protect themselves and those close to them and especially if they perceive that a very real personal danger exists if they speak out: "people are scared to talk, people are scared to be seen talking to police and telling them what happened, and stuff like that. So it would be like great, if you can just say whatever you want to say, report something anonymously" (F2)

The option to be anonymous is therefore crucial, especially when reporting on service delivery and corruption, as the fear of being identified would reduce the incidence of reporting. The results showed strong agreement to all three questions, indicating a desire to inform and report.

5.2.4 Community Interaction

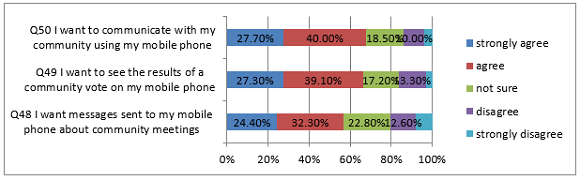

There are many different reasons why people don't interact, but mobile phone technology could be used to allow for more interaction (Figure 10).

The response to the statement, "I want messages sent to my mobile phone about community meetings", is positive. One of the interview participants related a situation where information or event notifications sent via a mobile phone would be helpful when making public announcements about upcoming public meetings. "It would be like very helpful, because sometimes you…don't know what is going on. You have no idea what people are saying, or if there's a meeting and stuff. Or you missed the time when the guys are shouting like there's a meeting at 7 o'clock." (F2). However, a similar study by Bagui et al. (2011) indicated that ward councillors shared a different perspective on community meetings, as it appears that notification of meetings only go out to ward councillors and forum members.Besides receiving information directly from government, or related to government services, there was also interest in other information generated by citizens. Interaction and sharing of information in the community would not only benefit those in the community, but 'crowdsourcing' could enable local government to gain insight, and make better decisions based on input from constituents. The increased communication between community members would also strengthen social capital, which would help to increase political participation.

5.2.5 Communication with the Local Councillor

Local councillors play an important role as political representatives elected by communities. The expectation is that that they will deliver to their constituency what was promised before the election. It is therefore important that constituents can easily communicate with their local councillor to ensure that they are fulfilling their mandate.

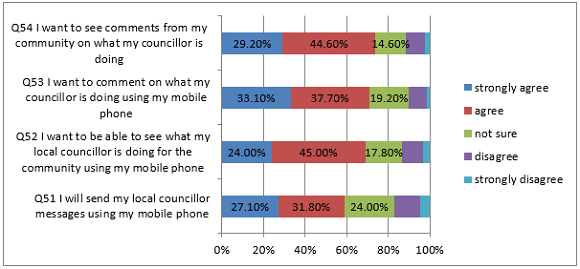

Respondents show a definite interest in communicating with a local councillor as well as dialogue between the councillor and other constituents (Figure 11). Feedback offered to councillors can be used to better serve their constituency as well as to gain insights into some issues or concerns that may not yet have surfaced. The ability to report empowers citizens and allows them to influence government where it matters most for them, on the local level. However this may meet with resistance from some politicians, who may not agree with the level of transparency that this would bring. Constituents would not only be able to monitor their local councillor but also review their past performance. This would help them decide whether to vote for the same councillor in the next election. From a provincial or national government point of view, it could also be a monitoring tool allowing them to intervene where necessary.

5.3 Areas of Concern

Respondents were also probed around a number of possible barriers or areas of concerns namely the issue of trust, security, and privacy, as well as cost.

The majority of respondents indicated that they did not trust the government (32% did not trust the government and a further 30% were unsure). Furthermore, only 41% of survey respondents expected the government to protect their privacy during their mobile interactions. This spread of views is supported by the different comments of the interview participants: "I don't trust them" (F1) versus "I do trust the government" (M1). The study by Bagui et al (2011) confirms this lack of trust and further reports a "bad image of politics".

Respondents were still concerned with security, as only 41.4% perceived no risk. Security and respect for privacy in electronic systems is crucial to user acceptance (Brücher & Baumberger, 2003; Buellingen & Wortner, 2004; Carroll, 2005; Haque, 2004; Grant et al., 2010; Poblet, 2011). Not only must the system prevent data manipulation during transmission, but also, the identity of the sender should be unmistakably verified (Brücher & Baumberger, 2003).

With the anticipated uptake of smartphones, security is more important as there is an increase in attacks on these devices (Becher, Freiling, Hoffmann, Holz, Uellenbeck, & Wolf, 2011). In addition, "computer viruses are now airborne" (Hypponen, 2006, p. 70), and some of the challenges faced include vulnerability to hacking, as well as the interception of signals broadcast via wireless networks. Added to this is the high risk of theft or loss of mobile phones which could potentially carry personal information (Trimi & Sheng, 2008). The use of mobile Internet potentially also exposes users to web browser vulnerabilities and exploits (Becher et al., 2011). Despite warnings of a security risk, many users blindly accept unknown files and follow links sent to them (Hypponen, 2006).

The digital divide is the gap between those with access to ICTs and those who do not (Chigona et al., 2009). Lack of access to ICTs have been equated with limiting opportunities for citizens, and the South African government has responded by putting the necessary regulatory framework in place to address this. Agencies and bodies such as the Government Information Technology Council (GITOC), and the State Information Technology Agency (SITA) were created to ensure that e-government services were made available to all citizens (SITA, 2011). Even so, delivery has been ineffective, due among other reasons, to tension over management structures and internal power struggles (Cloete, 2012).

The long held monopoly by Telkom (national telecom operator) also did not help with the supply and delivery of the required infrastructure for the provision of Internet services. And, despite the introduction of a second network operator, fixed-line Internet costs are still too high for many (Mutula & Mostert, 2010), especially for those living in rural areas. Nearly forty five percent of the South African population lives in rural areas (Mutula & Mostert, 2010), and in some cases the closest access to government facilities could be as much as a two day walk (Twinomurinzi & Phahlamohlaka, 2005 ; as in Twinomurinzi, Phahlamohlaka, & Byrne, 2012). Low penetration of personal computers, necessary for access to the Internet, led to the provision of access via public access terminals at 'multi-purpose community centres', libraries and the post office (Mutula & Mostert, 2010), but these have proven to be unsustainable (Singh, 2010).

SITA recognised the importance of mobile government because of the ubiquity of mobile phones along with the greater coverage of wireless networks in rural areas. Although mobile phone and wireless networks may appear to have addressed the digital divide, it does pose some obstacles of its own. As a developing nation, cost (or affordability) remains an important concern for all mobile interactions, especially in South Africa with historically high costs of mobile telecommunications (Chigona et al., 2009; Bagui et al., 2011). And, despite the introduction of lower mobile Internet tariffs, it still remains too high for the majority of South Africans.

Widespread implementation of mobile government services is lacking, with most being rudimentary and informational, such as SMS notification services from the Department of Home Affairs (Cloete, 2012). While there are a few mobile government implementations the potential of mobile services has not been properly explored by the South African government (Mutula & Mostert, 2010). Both Brücher and Baumberger (2003), as well as Haque (2004) indicate that government should form a relationship with mobile operators to ensure low cost or even free access to government mobile services. Buellingen and Wortner (2004) raise issues of reliability of service, which is echoed by Chigona et al. (2009) who cite concerns over mobile connectivity in South Africa.

Interestingly in this study the number of respondents prepared to communicate with government remained the same (79%) regardless of whether the service was free or low cost. In the interviews, it became clear that respondents were fully conscious of the potential cost saving. At first F1 was adamant that she was not going to incur any costs: "I don't want to. I would use my airtime" (F1) but, after some further discussion, she came to the realisation that that "I would save taxi money" (F1). The indirect cost savings of using mobile Internet, such as the time saved on travelling or standing in queues, was confirmed in a study conducted by Chigona et al. (2009).

Indications are that there would be demand for appropriate services where it is clear that any additional costs could be offset against the benefits derived. Arguably, more efficient revenue collection was the driver behind the deployment of the SARS services. The implementation however is an indication of the capability for government to deploy transactional, two-way mobile services, however "constraints include a lack of political will and support; a lack of strong and consistent leadership; a weak and contradictory IT governance framework; and continuous political and bureaucratic infighting." (Cloete, 2012, p. 138).

6. IMPLICATIONS

The survey presented a list of some government mobile services. The introduction of services would be a very good starting point upon which others could build. High on the list was a public transport information service where citizens could access bus and train timetables, as well as receive warnings of delays or cancellations. There was also keen interest in being able to locate government clinics or offices, communication with the Department of Labour, as well as receiving job ads. The list of services could be extensive, and interview participants mentioned some other G2C and C2G services that they would like to see: "criminal, crime reports" (F2); "I would report over full taxis." (F1) "I would like to inform the police about crime" (M1)

M-government services would not only be easier to create but would also be met with the least amount of resistance when compared to m-democracy applications. As mentioned before, voting may raise concerns around secrecy, privacy, and security. Far easier to implement and less likely to raise the same concerns, are 'quick polls'. Initially it could be used as an effective way for a local councillor or for citizens to quickly gauge community opinion on a variety of issues. The bigger plan for the quick polls system should be that it evolves it into a fully-fledged voting system. Over time it could be used as a testing environment, while addressing secrecy, privacy and security concerns. When finally implemented as an election voting system, the transition would be familiar, and seamless to users.

However, this degree of openness may be idealistic. The proposed Protection of Information Bill is an example of the lengths to which the South African government will go to keep some things 'under wraps' and ultimately go against section 16 and 32 of the South African Constitution which states that, anyone should be allowed access to information, and everyone has the right to freedom of expression.

A comment or chat network would allow for the communication and the sharing of ideas between individuals and communities, helping to build bridging capital, and the much touted 'rainbow nation'.

The high interest in wanting to report service delivery problems and corruption, and the lack of trust in government was evident in this research, which indicates that the level of social capital between government and ordinary citizens is extremely low. However, reporting and monitoring services could potentially be problematic from a political rather than a technical point of view. Increased transparency, as well as exposure to public scrutiny of some processes could possibly lowerl the incidence of tender irregularities, endless service delivery complaints and corruption. The tables would be turned, and ironically, citizens could become 'big brother'. However, certain politicians may not be comfortable with being continually questioned, and having their every move subject to public scrutiny.

7. CONCLUSION

Although the Constitution of South Africa supports political participation, the mechanisms provided still prohibit many from interacting. Mobile phones are an integral part of everyday life for many people: "My whole life is on there" (F1). The widespread acceptance and adoption of mobile phones in South Africa makes it the perfect vehicle for citizen interaction with both their community, and with government. One interview participant summed it up as follow: "if the youth access it through their mobile phones it will be so much easier, so much quicker, cause it'll be convenient" (M2)

Of all the UTAUT variables tested, the only two statistically significant drivers for the intention to participate in M-government were found to be the Performance Expectancy construct relating to the convenience of using the mobile device and the Effort Expectancy construct of the user's proficiency with the device. This finding is reminiscent of the parsimony of the original Technology Acceptance Model.

There is great interest in the specific G2C and C2G mobile services mentioned in the survey, and this is possibly a reflection of the respondents' perception that these services would offer personal value. Brücher and Baumberger (2003) noted that services have to offer value to ensure widespread use. Although there does appear to be some interest in voting using mobile phones, voting via mobile phone is likely to be controversial, with concerns over secrecy, privacy, and trust. Trust in the system is best built over time as citizens become familiar with the systems as they use other G2C and C2G services.

Issues around mobile security can also negatively affect trust. Providing public transport information or job advertisements could be considered as 'safe'. However, an application that either held, or transmitted medical information over wireless networks could be compromised by mobile malware or other security exploits. Even though these security breaches may not originate from the service provided, and rather be as a result of user bad practices, potential security breaches need to be taken into consideration before deploying mobile government services.

Respondents also expressed interest in being able to report on service delivery and corruption, as well as communicate with their community and local councillor. Mobile phones serve to empower citizens and can give them the ability to access information, report and communicate more easily than before.

Some considerations for future research are to expand the sample, not only to increase the representativeness and size of the sample, but also to include other age groups. Additionally, the research could focus on services people want or need: as well as the typical government information services offerings, focus groups could be conducted to develop a list of services that citizens really want.

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa). It would not have been possible without the enthusiastic participation of our survey and interview respondents. An early, short version of some of the main findings in this article was presented at the 12th European Conference on E-Government and the authors are grateful for the constructive feedback of the conference reviewers and participants.

REFERENCES

10. Appendix: Selected Portions of Research Instruments

The research instruments were compiled in English, then translated into both Xhosa and Afrikaans given the demographics of the sample in the Western Cape.

The survey questionnaire consisted of three parts.

- Part 1 asked for the following demographic information: gender, age group, home language, highest level of education and capabilities of the respondent's mobile phone (SMS, email, Internet, camera, Java apps, games, radio, music player).

- Part 2 included 28 statements corresponding to the various constructs related to the influencing factors i.e. the Unified Theory of Adoption and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and Social Capital Theory (SCT) constructs. These were answered using a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly agree to Strongly disagree).

- Part 3 contained statements relating to the other

research objectives. The following are the statements

included in the instrument:

- I am interested in politics

- Government looks out for me

- Besides voting, I can change what government does

- I communicate with my local councillor

- I can influence what politicians do in my community

- I trust government to protect my privacy

- I would use my phone to vote on community issues

- It would be nice and easy to report community problems like trash removal using my mobile phone

- I would use my phone to get information from government

- I would complain about service delivery using my phone

- I would use my phone to report on corruption

- There are no security risks in using my mobile phone

- I would like to get suitable job adverts sent to my phone

- I would like interact with the Department of Home Affairs using my mobile phone

- I would vote in national elections with my mobile phone

- I would vote in municipal elections with my mobile phone

- I would vote in a quick poll on community issues with my phone

- My privacy won't be violated if I use my mobile phone to interact with government

- I trust government

- I want messages sent to my mobile phone about community meetings

- I want to see the results of a community vote on my mobile phone

- I want to communicate with my community using my mobile phone

- I will send my local councillor messages using my mobile phone

- I want to be able to see what my local councillor is doing for the community using my mobile phone

- I want to comment on what my councillor is doing using my mobile phone

- I want to see comments from my community on what my councillor is doing

- I would use a government medical information service on my phone

- I would like to be able to use my phone to find government facilities such as clinics and offices.

- I want to be able to interact with the labour department to ask questions about my pay, leave, or working conditions.

- I would use my phone to get public transport information (train and bus time tables, and messages about delays)

- If I was on the government housing list, I would like to receive messages via mobile phone

- I would get the best mobile phone I could afford

The protocol for the interview included the following questions (with additional prompts indicated):

- If you could use your phone to communicate with

government, what services would you like to see?

- Information, notifications, vote (why / why not), simple polls, comment on issues, reporting(govt. officials, corruption, service delivery issues)

- Is there any reason/s that you would not want to

communicate with government using your mobile phone?

- Security, privacy, cost

- Do you find it easy to communicate with government,

and if not, why not?

- SARS , Home Affairs, queues, filing in forms, Local councillor

- Why would you want to use your mobile phone to

communicate with government?

- Save time, money (travel, queues, etc.), convenient, easy to do, can do it as something happens!

- Is there anything about using your mobile phone that

you find difficult?

- Language, navigation, small screen, buttons, predictive text, menus

- Loading applications, etc.

- How involved are you in your community

- How much, if not why not? Trust?

- Generally too busy, or don't feel its worth it?

- If you do belong to a club/group, which groups do you belong to, why?