Community & Technologies, Community Informatics: Tensions and Challenges for Renewing Democracy in the Digital Era

Civic Informatics Laboratory, Computer Science Department, Università di Milano, Milan, Italy. Email: [email protected]

Introduction

From their very beginning ICTs (information and communication technologies) have been applied in and shaped organizations and society. For quite a long time, the adoption of ICTs within organizations was carried on to support hierarchical organizations in the private and public sectors, with frequent implementation failures due to the freezing of ideal (formal) procedures into software. Socio-technical (Mumford, 1985) as a pointer to this branch of literature) and participatory design approaches (see for instance (Briefs, Ciborra and Schneider, 1983), Schuler and Namioka (1993), (Bødker, Kensing and Simonsen, 2004) have been proposed as a way of understanding the real behavior of organizations, so as to avoid failures and preserving the quality of working life.

The specific kind of organizations called "communities" have been first introduced by the German sociologist Ferdinand Toennis to explain the changes occurring in society in the late XIX century (Toennis, 1887). He introduced the distinction between Gesellschaft (a well-structured organization, or "society") and Gemeinschaft (commonly translated as "community"). The main difference between them lying in the existence of a (formal or informal) contract among the participants of a gesellschaft (society), while a community may be described - in the more general sense - as a web of personal and social relations, held together by a variety of circumstances.

In the '70-'80's of the XX century, two mutual related phenomena emerge. On the one hand, the gesellschaften begin to adopt less hierarchical structures that allow them to better respond to a market and a world, more and more dynamic. On the other hand, computer systems evolve from the monolithic EDP (Electronic Data Processing) model, typically implemented in general-purpose mainframes, to more and more distributed architectures. Together, these two changes open a new perspective, which was well captured by Terry Winograd in an unpublished note (1981):

"In the decentralization of work and the distribution of expertise we see a movement toward reducing our dependence on centralized structures and expanding the importance of individual "nodes" in a network of individuals and small groups.

The use of computer communication in coordination makes it possible for a large heterogeneous organization to function effectively without a rigid structure of upward and downward communication.

This shift does more than reorganize the workplace. It puts forth a challenge to the very idea of hierarchical organization that pervades our society. It may open a new space of possibilities for the kinds of decentralized communal social structures that have been put forward as solutions to many of our global problems."

In this context "communities" gained new attention as emerging forms of online aggregations, mainly because of the "intuition" of Howard Rheingold who called "Virtual Communities" the social relationships which emerge when a BBS (Bulletin Board System) is used to enhance and strengthen social ties among people in a local area, and beyond (Rheingold, 1993). The movement of Community Networks (Schuler, 1996) re-enforces Rheingold's intuition, with communities being recognized as of significance in the business sector, where "communities of practice" are seen as having value since they foster knowledge creation and sharing (Wenger, 1988), (Wenger, McDermott, Snyder, 2002), (Faraj, Jarvenpaa, Majchrzak, 2011). Software technologies, which enable virtual/digital/online/web communities, are largely inspired and based in Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) and groupware applications.

However, as Jenny Preece observed (Preece, 2000) "superficially, the term online community isn't hard to understand, yet it is slippery to define." Faraj, Jarvenpaa, Majchrzak (2011) go further and argue that online communities are "fluid objects" whose dynamic depends on tensions that enlighten different, co-existing factors. Similarly, tensions do exists between the two groups of researchers that focus on the interplay between communities and ICTs: on the one hand, Community&Technology, mainly established around the biannual C&T international conference, rose in 2005 as a branch of the biannual ECSCW (European Computer Supported Cooperative Work) Conference; on the other hand, CI, having the Journal of Community Informatics (JoCI), the "ciresearchers" mailing list and the annual conference hosted in the Monash Center in Prato, Italy as its main venues.

Learning from Diversity

Three main "tensions" feature the diversity between C&T and CI, both quite well established disciplinary areas. Highlighting these tensions is a fruitful way to enlighten the field and provides opportunities for a better understanding and more effective action.

- A first tension between the two "sides" of the two groups: there are researchers focusing mainly on communities (how they are supported, shaped, enabled, empowered, destroyed? by ICT), while other researchers mainly develop technologies (that support, shape, enable, empower, destroy? communities). The actual and deep interplay between the two perspectives is less frequent than one would expect, and seldom occurs. Those who work with communities are faced with such great and urgent needs that they are led to consider and use existing technologies and focus their attention on social issues and outcomes. Also developing software is a complex task, and those who are engaged in it are led to limit social issues to the appropriate design of user interfaces, user experience, interaction design and the like. The recent financial constraints - limiting resources available for research projects and social initiatives - worsen the situation.

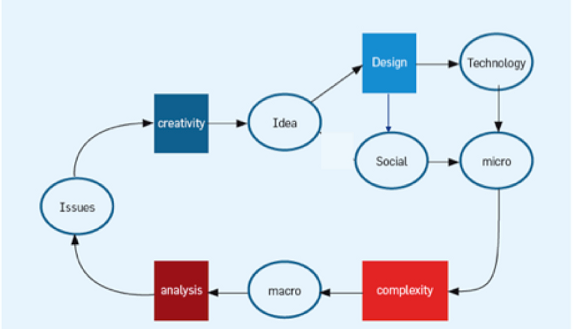

- A second tension between

research and

action. I would like to argue

the need for a tight connection between these in this

field by referring to Figure 1 (slightly changed) used in

(Hendler et al. 2008) to illustrate the challenges that

the (social) web presents to software engineering and

application development. The picture indicates that

applications:

- come from a creativity event ("Idea");

- have to be designed considering both technological and social aspects;

- after being developed and tested in the "micro" (typically a lab), have to face complexity by being tested in "the macro", i.e., in initiatives with "real" users taking place in real-life settingsi ;

- the outcomes of these initiatives have to be carefully analyzed - also in terms of the desired vs. achieved impact (Smith, Macintosh and Millard, 2011) - to iterate the process.ii

The lack of a tight connection between research and action is a source of serious problems: researchers who develop prototypes without testing them in real cases lose relevance in relation to the companies that deploy their innovations; activists who undertake field projects (to support communities) without a scientific solid background run a greater risk of failure and doing damage. - A third tension between the two halves of the world: the once-called "developed countries" which are passing through a dramatic crisis, and the once-called "developing countries" which are now the only ones which in some ways are still "developing". Because of this, differences are somehow shrinking, enhancing the possibility to learn, each from the other side.

Roughly speaking (may be, too roughly), the C&T group privileged technology and research in the developed countries; the CI group privileged communities and action in developing countries. Encouraging a merging between these poles would allow tensions to stimulate reasoning through diversity.

A Major Challenge

CI/C&T action research uses and develops technologies mainly rooted in CSCW. In its turn, CSCW arose from the above-mentioned failure of procedure-based Information Systems to support white collar and knowledge workers and managers. This is not a mere technological evolution. As Winograd suggests in the above quoted claim, the vision, and the challenge, is that the use of computer communication makes it possible for a large heterogeneous organization to function effectively without a rigid structure of upward and downward communication." "This shift" he says "puts forth a challenge to the very idea of hierarchical organization that pervades our society. It may open a new space of possibilities for the kinds of decentralized communal social structures that have been put forward as solutions to many of our global problems." [Italics by the author]

Unfortunately, the tension towards innovation gradually faded away from CSCW and the field suffered because of the increasing role, expectations and goals of the big software companies. In the same years, emerging grassroots initiatives such as virtual communities, free nets and community networks kept alive the original tension towards ICT-empowered social innovation. Community Informatics and C&T come from these efforts, and the recent Community Informatics Declarationiii captures the idea that "the Internet is a social environment, a community space for people to interact, to develop and exercise their civic intelligence and work together to address collective challenges." But the Internet has also become a huge machine for surveillance and ultimately for individual and social control (Morozov, 2011), (Greenwald, 2014).

In this scenario, the merging of the efforts and perspectives of CI and C&T should and could help face the challenge. Social media have been effective in empowering civic engagement, protests movements and political activisms (see for instance (Wulf et al., 2013a) on the Tunisian revolution and (Wulf et al., 2013b) on a Palestinian demonstration movement). As Manuel Castells wrote (Castells, 2012): "the precondition for the revolts was the existence of an internet culture, made up of bloggers, social networks and cyberactivism."

However, the step from protest movements to a different way of managing public affairs is substantial (De Cindio and Peraboni, 2010). If and when activists engaged in field projects of social change are successful, they need to find ways to let their grassroots movements evolve into organizations able to govern themselves and the society, without losing people' expectations of participating and getting involved in decision-making. Can technologies conceived and designed for different purposes and for a different audience support this evolution from protests to a democratic and distributed government? Can the construction of new organizations, of a new society based on effective and sustainable forms of people's involvement in policy making, of a democracy for the digital era (Kaldor, 2013), be actually based in Facebook, Twitter and the like?

Facing these challenges requires a major effort in the development of technology (again from the "research program" envisioned in the 1981 Winograd's note) "to enable large heterogeneous organizations to function effectively without a rigid hierarchical structure." While communication and coordination aspects have since then been widely considered and implemented, what is still missing are comprehensive software solutions able to deal with issues such as:

- effective deliberation and decision-making in (large) distributed organizations (grassroots movements as well as small businesses around the world) (Concilio and De Liddo, 2015)

- knowledge gathering, composition and sharing (with argumentation features to support deliberation) in (large) distributed organizations (Convertino et al., 2015).

Several promising efforts in these directions do exist, but an extensive review is out of the scope of this note. Italian as well as international experiences are presented in a dossier by the Italian Senate about the development and the use of civic media (Senato della Repubblica, 2013) that provides evidence of such efforts and of their early results. It is worth mentioning, among the others, respectively: (a) the online deliberation software LiquidFeedback, developed "to empower organizations to make democratic decisions independent of physical assemblies while also giving every member of the organization an equal opportunity to participate in the democratic process." (Behrens et al., 2014, p.13); (b) tools such as Compendium, Evidence Hub, Deliberatorium, coming from the extensive effort for developing argumentation and visualization tools that is ongoing at the Knowledge Media Institute of the Open University (De Liddo and Buckingham Shum, 2014) and at the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence (Klein, 2012).

However, not only technology matters in facing those challenges. All these software applications implemented in a specific context are situated, socio-technical systems (Dourish, 2004). The specific socio-political and cultural environment is influential in determining either the success or the failure of each online deliberation initiative. Let's consider the case of LiquidFeedback: it is an open-source software conceived of and designed by activists in the Pirate Party of Germany, a closed and homogeneous group, to aid their internal decision-making processes (Domanski, 2012). We have contributed to its use (embedded into a richer website) in two larger Italian civic contexts, i.e. open to the general public. (Bertone, De Cindio, Stortone, 2015). The analysis of these two initiatives shows that the different outcomes can be partly explained by the fact that one as compared to the other shows some distinctive traits of a community in terms of collaboration and a strong sense of commitment.

These cases suggest that the effectiveness of these tools in supporting new forms of democratic governance and distributed decision-making is greater if the target organization is familiar with technology and shares a rich gemeinschaft. Both these features are present in a couple of political movements that are gaining national relevance in their countries: the MoVimento 5 Stelle (literally "Five-Star Movement") in Italy, which is now the second largest Italian party, and Podemos in Spain. Local groups of the MoVimento 5 Stelle tested LiquidFeedback, and now activists in M5S Lazio are developing a LiquidFeedbackfork called PARELON (Parelon - PARlamento ELettronico Onlineiv ) as a tool for M5S representatives elected to regional councils. Local groups of Podemos are using Loomio , which is again, a fork of LiquidFeedback, developed by activists in New Zealand. Loomio's slogan is "the easiest way to make decisions together." Hopefully, research will analyze the outcomes of these experiences.

It is worth continuing testing these tools also for a larger and open audience of citizens. Again, taking advantage of the lessons learned in the early experiences mentioned above, we believe that local initiatives have more chance to succeed. Especially, the city looks to be an appropriate social environment as it provides a good gemeinschaft dimension: sense of belonging, occasions for physical meetings, people orientation to solve together some basic needs.

In the last decades of the XX century, these traits have been sustained by online initiatives such as community and civic networks (Schuler, 1996). The "Social Streets" (www.socialstreet.it) are online social aggregations that recently became popular in Italy. The mimic community networks in the new technological setting, by using Facebook as their organizing platform. As community and civic networks suffered from their low impact on city life (De Cindio and Schuler, 2012, p.2) and then disappeared, the social streets may follow the same trajectory if they are not able to envisage ways for making the social relationship they help to establish somehow effective for allowing citizens to have a say. However, recent experiences of ICT-enabled Participatory Budgeting (Stortone and De Cindio, 2014) indicate that it is indeed possible to establish decision-making practices involving from hundreds to thousands of citizens (depending on the city size). Though further experiences and their rigorous analysis is still necessary, we believe that the local/city context more than the regional/state/national one can lead to an envisaging of new forms of democratic, active, informed participation to the public life.

As Ceccarini (2015, p.30) maintains in his recent book "La cittadinanza digitale" ("Digital Citizenship"), the decline, the disenchantment, the malaise, the distrust, the "partisan de-alignement" (Dalton, 1994) between the citizens and politics refer to the traditional modalities of civic engagement: first of all, the vote and political parties, more in general participation through membership in organizations based on delegation/representation. This does not necessarily imply a citizens' de-engagement, but calls for a new model of "taking part" in the digital era, where online and offline are the two sides of the hybrid global world. The hope is that the merging of the two research communities contributes to answering this challenging demand.

Acknowledgements

I'm greatly indebted to the anonymous referees and to the editors whose critical but encouraging comments allowed a substantial improvement of the paper.

Endnotes

- I took this expression from Kari Kuutti (Univ. of Oulu) online profile

- It may be worth recalling that Hendler et al. (2008) mention Doug Schuler's Public Sphere project (at that time at the URL trout.cpsr.org, now moved to www.publicsphereproject.org) as a way to "explore[s] how the Web can encourage more human engagement in the political sphere. Combining it with the emerging study of the Web and the coevolution of technology and social needs is an important focus of designing the future Web."

- http://cirn.wikispaces.com/An+Internet+for+the+Common+Good+-+Engagement%2C+Empowerment%2C+ and+Justice+for+All

- https://www.parelon.com

- see for instance: https://www.loomio.org/g/jI6iBoCJ/cercle-podem-algiros-podemos-algiros, https://www.loomio.org/g/u9fpRL6x/circulo-podemos-villanueva-del-pardillo