CI 101: Community Informatics as General Education

- Distinguished Professor, College of Information Sciences and Technology, The Pennsylvania State University, PA, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

- PhD Candidate, College of Information Sciences and Technology, The Pennsylvania State University, PA, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

In some countries, all undergraduate university students are required to complete a common program of specific courses, or categories of courses, in order to earn a degree. These general education courses are conceived of as complementing courses in a student's major program of study; they embody educational breadth, in contrast to major program depth. The topics of general education courses span many areas including communication and speech, fine and performing arts, health and physical education, history, humanities, mathematics, natural science, philosophy, religion, social science, writing and composition, and, more recently, global studies and technology.

General education can comprise a very significant proportion of undergraduate education; for example, in the US, where an undergraduate degree consists of about 40-45 courses taken in a four-year program of study, a survey reported that students are required to take 14-17 general education courses (Warner & Koeppel, 2010), about 1/3 of the total number of courses they take.

Historically and currently, general education is a conceptual fulcrum for university education. For example, the (European) classical/medieval model of university education was a one-size-fits-all general education curriculum focused on a canon of Greek, Latin, mathematics and moral philosophy, and the goal of preparing a leadership class to perpetuate a common culture (Boning, 2007). The Industrial Revolution and the emergence of democratic societies in Europe and North America undermined this model. Throughout the 19th century, university curricula differentiated, incorporating elective courses and alternative programs of study. For example, the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862, in the United States, provided funding in every state for new universities focused on agriculture and engineering. By the early 1900s, concerns about curricular coherence pushed the pendulum of general education back into the spotlight.

The modern concept of general education is more pragmatic than the classical/medieval model (Dewey, 1966). One general education objective is that of placing specialized learning in the context of culture, citizenship, and engagement with life. General education courses should help students to make sense of their more specialized courses, to relate their educational experiences to their life experiences. General education should help students become more aware of the world, and to be more responsible and autonomous in the world. A second objective is to provide a foundation of knowledge and skill to enable further and continual learning and development throughout life. Students should be able to think logically and critically and to write clearly, to collaborate creatively and effectively, to find, assess, and integrate information, to understand diverse kinds of knowledge, and economic, cultural, political, and social systems. (See Boning, 2007; Wang, 2014).

Abiding tensions remain in the concept of general education. For example, some universities have specific required courses or activities for all students. In Warner and Koeppel's study (2010) most American universities had required specific courses for writing and composition. Other universities have only course distribution requirements, but students' choices can range from among 5 courses to from among more than 60, depending on the school (Warner & Koeppel, 2010). General education is an open process of identifying and articulating new vehicles for educational breadth, such as critical perspectives (women's studies, black studies) and new socio-technical possibilities (television, multimedia, digital life).

In this article, we propose that community informatics can contribute uniquely to current conceptions of general education. We outline a notional course proposal for a freshman-sophomore level, that is, lower division general education course in community informatics. Our longer-term objective is to make it more possible for all universities to adopt community informatics as a general education course available to students. Our immediate objective in this paper is to engage colleagues in a discussion of how the longer-term objective can be advanced; that is, to develop and refine our specific course proposal, to analyze what such a proposal should look like for various cultural/educational contexts (we are working in the US), and to formulate a plan or plans for moving ahead toward the design and implementation of a general education community informatics course option.

WHY COMMUNITY INFORMATICS?

Community is a highly significant conceptual lens for understanding human history and human experience. This includes analysis of prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies, the emergence and organization of Neolithic villages, Tönnies's reaction to industrialization in 19th century Germany and related European work on solidarity and isolation, American community sociology from 1920-1950 especially, Warren's analysis of macro-system dominance and the "great change" from horizontal to vertical integration; Putnam's demographic analysis of television; contemporary rural sociology; urban studies; and the great variety of studies of online community, community networking, and other Internet-mediated community arrangements. Technology, broadly understood, has clearly modulated community structures and experiences for at least 10,000 years. (See, for example, Carroll, 2012; Gurstein, 2007; Lyon, 1999; Rheingold, 2000).

Community informatics is taught at the graduate level in universities, typically those whose faculties include community informatics researchers. It can appear in a variety of disciplinary contexts, including communication studies, computer science, information science, library information systems, among others. Community informatics is a healthy and growing interdisciplinary area. This trajectory could be simultaneously supported and leveraged by creating a lower division, undergraduate general education focus. Many students who have never heard of community informatics, as such, have nonetheless thought about community and about technology. Helping students to fathom and articulate relationships between community and technology, both historically and with respect to their own personal experiences could be an engaging vehicle for general education.

Community informatics addresses the pragmatic objectives of contemporary general education. Studying community informatics can help students relate educational experiences to life experiences: University students are already embedded in diverse communities in different ways and to varying degrees. Many university students are in the intriguing situation of "residing" in two local communities, the community in which their parents still reside, and the community on or adjacent to their campus. In addition, most contemporary students are members of social media communities, notably, Facebook, and often several other, more specialized interest communities, such as online game communities and many extracurricular campus groups and activities. Indeed, university students are often in a stage of life where they easily form new attachments and explore social identity commitments. Society has a critical interest in nurturing the community-oriented interests and practices of university students. We live in a time of rapid change; it isn't clear that we can or even should want to merely replicate extant social structures. Nevertheless, our society depends on the emerging social practices of today's students, including their reappropriations of community.

Some students may not have reflected upon their current and future roles in communities, or critically analyzed the consequences and responsibilities of community membership. But they are precisely at a point in life where such reflections and critical analysis will do them, their peers, and all of society the most good. Community is an intimate and committed context for people to discuss and integrate information, work toward consensus with others in solving problems, and participate in governance and policy development. Thus studying community informatics can make communication, collaboration, problem solving, citizenship, and society more immediate and relevant to students. It is not difficult to see all the objectives of general education as not only within the scope of an introductory course in community informatics, but particularly well-addressed through critical consideration of community informatics.

A general education course in community informatics could leverage the university community itself, and the larger community in which the university itself is embedded. Project-based learning and service learning are obvious approaches and components of a community informatics course. After all, the local community is all around us, presenting myriad concrete opportunities to engage the real world while mastering the concepts and techniques of community informatics. And doing so enriches the local community as it provides learning opportunities: Campuses are routinely called communities by administrators, but they become communities when students, faculty and staff reflect on how they function as communities, and on new ways in which they could function as communities. But this is precisely what a general education focus on community informatics creates. This extends to the community beyond the campus as well: The town-gown stereotype of students who see the town as a dorm with bars, and town residents who see students merely as visitors who sometimes misbehave is limiting for all concerned. It does not serve the students, the town, or society. A general education course could leverage off-campus service learning possibilities, creating a more effective course experience, but also mutually engaging the student and the local community.

COURSE OVERVIEW

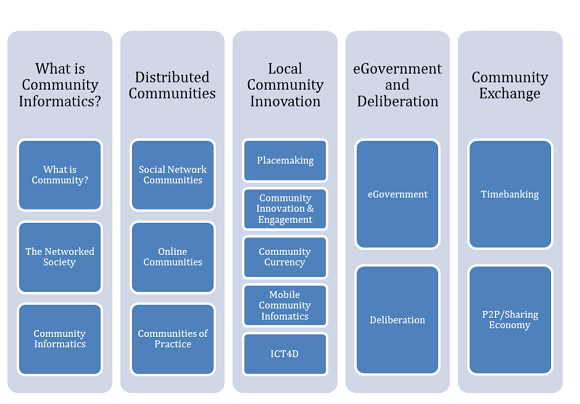

Our design for the course consists of five units. Unit 1 is an introduction to community informatics in which students will learn about the definition of community, ways in which community is being studied in academia, and some contemporary conceptualizations of community. While this unit will be largely focused on the transmission of knowledge to students, it will also involve some activities and in-class discussions designed to further students' understanding of the topics covered. This unit should logically occur first in the course as it provides a basis for students to think about community in the rest of the course. The following four units each cover a different category of community informatics - distributed communities, local community innovation, eGovernment & deliberation, and community exchange. Each of these units is comprised of multiple lessons that cover more specific topics within the category of that unit. These units are presented in an order in this article. However, it is not necessary for this to be the order when offering the class - each unit stands on its own.

Each unit consists of multiple lessons, each covering a specific topic in that unit's category. The number of lessons per unit varies from two, at the smallest, to five at the largest. These lessons were chosen as they cover topics that were determined to be of importance to community informatics. Each lesson could be conducted over one (or more, if necessary) weeks during the course. Readings have been suggested for each lesson. These are used to introduce important concepts of that lesson and further discussion in class.

While some of these readings are academic articles, many of them are from non-peer reviewed sources such as newspapers and blogs. Readings from these sources were chosen because they are timely and relevant to the topics being discussed. A decision was also made to stay away from serious academic sources that may be difficult (or boring) for younger undergraduate students to read and comprehend.

The readings will be kept up to date both as the class evolves and as time passes from their publication dates. This will keep the class relevant and discussing contemporary issues. In total there are fifteen lessons. This number may expand as more potential topics are brought to attention. The final number of lessons chosen for an offering of the class may include all of these proposed lessons or consist of a subset of them.

In addition to the main topics covered by the lessons of this course, there will also be several issues or themes that are discussed during the course. These are issues designed to spark debate within the class and as such are opinion based. Examples include trust, ownership, anonymity, and the ethicality of research. The issues are introduced in the lesson readings and as such the discussions for different issues are included as a part of different lessons. This does not mean that these issues must be included in those lessons but rather that the chosen readings do a good job introducing the issues and provoking thought. In future revisions of the course, the covered issues could change or the lesson in which each issue appears could be modified (depending on the new readings that are chosen). This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of community informatics issues but instead just interesting discussion points that relate in various ways to community informatics.

As previously mentioned each lesson is accompanied by some readings chosen to introduce the topic of that lesson as well as possibly bring to light some issues surrounding that topic. In addition to these readings, there will be other learning activities that students will complete in order to further their understanding of the concepts from the lessons including discussion sessions, out of class assignments, research assignments, and design thinking activities. Some examples of such learning activities are included in the course outline. However, instructors may adapt these and add new ideas as appropriate for their version of the course. For many of the lessons, in-class discussions will be used to allow students to reflect on what they think about the current topic and issues. Some sample questions to lead these discussions are included in the outline of the course.

Some of the lessons include the students conducting an assignment outside of class. For example, in the time-banking lesson, the students will participate in a local time bank and reflect on their experiences during an in-class discussion. These out of class assignments will allow students to learn by doing and experience first-hand the topics that are being discussed in class. Some of the lessons call for students to find specific examples of projects that exemplify the topic of that week. Students will be required to conduct research in order to find relevant sources that describe their project. This will also be an opportunity to inform these younger students about how to conduct research. Another potential type of research assignment might involve students tracking an issue in the CI Researchers mailing list ([email protected]) and leading a discussion of that topic in class.

The final type of learning activity that will be integrated into the course lessons is design thinking. This will involve students reflecting upon the concepts from the readings and class discussions and then brainstorming and refining the design for a project related to the topic of that lesson. They will also present their designs to the class. This type of activity will encourage creative thinking and encourage students to apply the concepts they learn in class. These four additional learning activities will add unique aspects to each of the lessons in the course and also further students' understanding of the material by causing them to consider it in different fashions.

To build upon the learning activities mentioned here, there will also be an end of semester project for this course. Students will form small groups for this project. Each group will then choose one of the topics covered in this course that most interested them. An action research project related to this topic will then be planned, with the instructor offering assistance as needed. These projects may be related to in-class activities, such as carrying out a project idea created during a design thinking exercise. Action research projects will allow students to learn more about topics that interested them but also engage with the topic on a more hands-on level.

We want to engage with community informatics scholars and other colleagues to criticize and develop this course proposal. We plan to implement a general education course in community informatics at Pennsylvania State University in the near future.

REFERENCES

APPENDIX: OUTLINE OF COURSE

Unit 1: What is Community Informatics?

Unit overview: This unit will familiarize students with basic concepts of community informatics. This includes the definitions of terms such as community, community informatics, and networked society. In addition, an overview of how community has been studied in academia will be given. This will include several ways in which community has been theorized, (for example, Tönnies's Gemeinschaft vs. Gesellschaft) as well as some contemporary studies of American community including the Lynds' studies of Middletown, Putnam's Bowling Alone, and the Berkeley Community Memory. The evolution of community over time will be discussed along with a brief overview of Maslow's hierarchy of needs explaining why humans gather in communities. Activities in this unit will show students first-hand their place in a community and the effect that technology has upon that community. This unit will form a base from which students will be able to think about community and community informatics issues that are touched upon later in the course.

LESSON 1: WHAT IS COMMUNITY?

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Explore the definition of community and

- Understand several ways in which community has been studied in academia

Activities

- Discussion on contemporary community & technology and community based on lecture given in class.

LESSON 2: THE NETWORKED SOCIETY

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Conceptualize the definition of the Network Society

- Compare and contrast the Network Society with other definitions of community

- Reflect on their position in the Network Society and their opinion of the concept

Activities

- Networked Society Dependence: Students will disconnect themselves from social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) for approximately 24 hours and record the social and psychological impact this has on them. An in-class discussion will be used to review the results of this activity and the students' observations.

- Networked Society Communication: This activity is an experiment designed to allow students to consider the validity of Rainie and Wellman's model of Networked Society communications and how it applies to their own lives. Over a period of time (perhaps 24 - 48 hours) students will record the communications they have with other individuals. They will record the time of the interaction, individual with whom they interacted, the type of interaction (social, schoolwork, etc.), and the medium of interaction (in-person, SMS, phone call, Facebook message, etc.).

LESSON 3: COMMUNITY INFORMATICS

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Define community informatics

- Give examples of areas where community informatics has been applied

Activities:

- Research: Each student will research one example of community informatics and share it with the class.

Unit 2: Distributed Communities

Unit Overview: This unit will cover communities that are located on the Internet or otherwise geographically distributed. This includes social networks (like Facebook and Google+), online communities focused on entertainment (such as Reddit) or knowledge (like Wikipedia), and communities of practice made up of practitioners of a particular field. This unit consists of readings that will be used to guide in-class discussions about various issues related to communities on the internet. Specific issues covered in this unit include: aspects of social networks that facilitate community interactions, the ownership of social network data, the ethicality of research about social networks, the stewardship of online communities, and the effect of anonymity in online communities. The communities of practice lesson will also involve a design thinking activity in which students design a community of practice for themselves and their fellow undergraduate peers.

LESSON: SOCIAL NETWORK COMMUNITIES

Lesson objectives: Students will:

- Identify characteristics of social network communities

- Discuss features of social networks that lend themselves to community interactions

- Reflect upon the ethicality of research conducted with social networks

Readings

- Jenkins, H. (2009, September 21). Is Facebook a Gated Community?: An Interview With S. Craig Watkins (Part One). Retrieved from http://henryjenkins.org/2009/09/is_facebook_a_gated_community.html

- Kratz, H. (2012, November 14). Why Google+ Is Better For Community Than Facebook. Retrieved from http://socialmouths.com/2012/11/14/why-google-is-better-for-community-than-facebook/

- Goel, V. (2014, June 29). Facebook Tinkers With Users' Emotions in News Feed Experiment, Stirring Outcry. Retrieved from The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/30/technology/facebook-tinkers-with-users-emotions-in-news-feed-experiment-stirring-outcry.html?_r=0

Activities

- Discussion

- Do social media make us less social, more social, or have no effect?

- What technological features are needed (or just better) to engage with a community?

- Who owns data, etc. in a social media community?

LESSON: ONLINE COMMUNITIES (focus on Reddit)

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Identify characteristics of different online communities.

- Discuss what makes an online community unique.

- Discuss the responsibilities of online community leaders.

- Explore the role of anonymity in online communities.

Readings

- Shaer, M. (2012, July 8). Reddit in the Flesh. Retrieved from New York Magazine: http://nymag.com/news/features/reddit-2012-7/

- Appelbaum, Y. (2012, May 15). How the Professor Who Fooled Wikipedia Got Caught by Reddit. Retrieved from The Atlantic: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/05/how-the-professor-who-fooled-wikipedia-got-caught-by-reddit/257134/

- Abad-Santos, A. (2013, April 22). Reddit's 'Find Boston Bombers' Founder Says 'It Was a Disaster' but 'Incredible'. Retrieved from The Wire: http://www.thewire.com/national/2013/04/reddit-find-boston-bombers-founder-interview/64455/

Activities

- Discussion

- The readings mentioned both Wikipedia and Reddit as online communities. What are some unique characteristics of each?

- Who decides what an online community's identity is?

- Who is responsible for the conduct of an online community?

- How does anonymity affect online communities? Is anonymity a good thing or bad thing?

- What are some other unique online communities?

LESSON: COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Define community of practice.

- Find and share examples of communities of practice.

- Go through the process of designing a community of practice, specifically for undergraduate students.

- Compare and contrast communities of practice with other types of communities covered in class.

Readings

- Cambridge, D., Kaplan, S., & Suter, V. (2005). Community of Practice Design Guide. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/nli0531.pdf

Activities

- Creating your own community of practice - Students will form small teams and work through the design process of creating a community of practice for themselves and their fellow undergraduate students. While faculty and graduate students generally consider themselves to be a part of the community of practice associated with their discipline, this seems to be less true for undergraduates. This activity will allow students to think through what an undergraduate community of practice would be like and reflect upon some potential benefits of such a community existing.

- Research

- Find an example of a community of practice

- Discussion

- What is a community of practice?

- Give an example of a community of practice

- What is the purpose of communities of practice?

- Compare and contrast communities of practice with other types of communities we have discussed in class.

Unit 3: Local Community Innovation

Unit Overview: This unit is centered on lessons about local communities that is communities that are geographically located in one location. The four lessons in this unit - Placemaking, Community Innovation & Engagement, Community Currency, and Mobile Community Informatics - are each areas of community informatics that depend on locally located communities. They each are also methods that can be used to undertake innovation within a community with the goal of improving it. The activities for this unit are focused particularly on design and other hands-on assignments.

For the Placemaking, Community Currency, and Mobile Community Informatics lessons, the students will first be learning about the basic concepts of these areas and then applying those in design thinking activities. These activities ask students to brainstorm methods in which these three areas could be applied in the local community where they live and go to school. The Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D) lesson will involve the students performing research about specific community-related ICT4D projects. The other lesson, Community Innovation & Engagement, will also require students to conduct a more hands-on activity but by going out and meeting with a local community innovation hub located in the community rather than a design activity. This is an organization with which work has previously been done and has indicated an interest in working with students.

LESSON: PLACEMAKING

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Understand the definition and basic principles of placemaking.

- Conduct a design-thinking activity to apply these concepts in a creative way.

- Discuss their designs with other students in the class.

Readings

- Project for Public Spaces. (n.d.). What is Placemaking? Retrieved from Project for Public Spaces: http://www.pps.org/reference/what_is_placemaking/

- Project for Public Spaces. (2008). 11 Principles of Placemaking. Retrieved from Placemaking Chicago: http://www.placemakingchicago.com/about/principles.asp

Activities

- Design thinking

- Students will form small teams and brainstorm ideas for placemaking projects that could take place in the local community (this could be on campus or downtown). They will then pick their most promising idea and expand the design. Each team will then present their chosen design to the rest of the class for discussion.

LESSON: COMMUNITY INNOVATION & ENGAGEMENT

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Learn about the concepts of community innovation & engagement.

- Further their understanding of community innovation & engagement by traveling to a local community innovation center and interviewing individuals working there.

- Research and present another community innovation project (from any location) to the class.

Readings

- Harvard Magazine. (2013, January). A Community Innovation Lab. Retrieved from Harvard Magazine: http://harvardmagazine.com/2013/01/a-community-innovation-lab

- New Leaf Initative. (n.d.). New Leaf Initiative. Retrieved from http://newleafinitiative.org/

Activities

- Discussion

- Find an example of a community innovation project and present it to the class.

- Community Innovation Center visit - Students will visit the local community innovation center and interview individuals there. The results of this trip will be discussed with the class.

LESSON: COMMUNITY CURRENCY

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Learn the definitions and concepts associated with Community Currency.

- Reflect upon community currency concepts and how they could be applied in their local community.

- Redesign the existing 'community currency' to incorporate other concepts learned in this lesson.

Readings

- Lietaer, B., & Hallsmith, G. (2006). Community Currency Guide. Retrieved from http://www.lyttelton.net.nz/images/timebank/community_currency.pdf

Activities

- Design thinking

- Lioncash redesign - Lioncash is a currency that can only be used in State College and some surrounding areas. It is associated with Penn State student IDs and can be considered as a community currency. However, in its current state, it has few of the effects and benefits of a more traditional community currency. After splitting into small teams, students will use the worksheets in the Community Currency Guide and think about how they could redesign the local 'community currency' (Lioncash) to be more of a community currency.

LESSON: MOBILE COMMUNITY INFORMATICS

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Learn the definition of mobile community informatics.

- Reflect upon the implications of location-based services in community informatics applications.

- Apply the concepts learned through the brainstorming and design of a mobile community informatics application.

Readings

- Kessler, S. (2011, June 28). Clever Foursquare Hack Turns New York City Into a Giant Game of Risk. Retrieved from Mashable: http://mashable.com/2011/06/28/world-of-fourcraft/

- Carroll, J. M., & Kropczynski, J. (2014). Mobile Community Apps as an Innovation Infrastructure. Human Computer Interaction Consortium 2014. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/12128851/Mobile_Community_Apps_as_an_Innovation_Infrastructure

Activities

- Design thinking

- Students will form small teams and brainstorm some mobile community informatics applications. They will then present their ideas to the class for discussion.

- Discussion

- What does the addition of location based services do for community informatics applications?

- What are some other potential applications of location-based community apps?

- How could you design a mobile community informatics application for use here on campus?

LESSON: INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES FOR DEVELOPMENT (ICT4D)

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Give a definition of ICT4D and explore concepts related to ICT4D (e.g. the Digital Divide)

- Find and share examples of ICT4D projects that are related to community and community informatics.

- Reflect upon the role of community in ICT4D and development in general.

Readings

- SOS Children's Villages. (2014, August 20). What is ICT4D, and how is it transforming lives? Retrieved from SOS Children's Villages: http://www.soschildrensvillages.org.uk/news/archive/2014/08/what-is-ict4d-and-how-is-it-transforming-lives

- Rutstein, D. (2014, April 4). ICT4D: A Coming of Age. Retrieved from UNICEF Connect: http://blogs.unicef.org/2014/04/04/ict4d-a-coming-of-age/

Activities

- Research

- Find an ICT4D project that has something to do with community - Students will research various ICT4D projects with the goal of finding projects that are more closely related to community and community informatics.

- Discussion

- What is ICT4D?

- Discussion of everyone's ICT4D examples

- What role does community play in ICT4D?

Unit 4: eGovernment and Deliberation

Unit Overview: This unit addresses eGovernment and eCitizenship and the effect they may have on communities. Readings for this unit cover existing applications of these two concepts and will provide students some background with which to discuss issues surrounding these two concepts. The issue of anonymity will be revisited and social justice will also be discussed. In addition, students will reflect upon the benefits and drawbacks of technologies such as those in the readings.

LESSON: DELIBERATION

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Explore technological applications that can be used for political and social deliberation.

- Reflect upon the effect that these applications have upon the communities where they are being used.

- Share personal experiences with similar platforms

Readings

- The GeoDeliberation Project. (n.d.). The GeoDeliberation Project. Retrieved from http://geodeliberation.webs.com/

- Ramos, D. (2015, March 29). Yik Yak schools college administrations on some truths. Retrieved from The Boston Globe: https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2015/03/28/yik-yak-schools-college-administrations-some-truths/KjcBlCA3wx1gu5jlVlH21I/story.html

Activities

- Discussion

- What effect do you think technologies like Yik Yak and GeoDeliberator can have on a community?

- Is anonymity essential to this? Is it counter-productive?

- How can deliberation technologies contribute to social justice?

LESSON: E-GOVERNMENT

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Understand the definition of eGovernment.

- Explore a real-world application of eGovernment.

- Reflect upon their own experiences with eGovernment and identify the strengths, weaknesses, and implications of eGovernment applications.

Readings

- United Nations Public Administration Country Studies. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from UN E-Government Survey: http://unpan3.un.org/egovkb/en-us/About/UNeGovDD-Framework

- Schnurer, E. (2014, December 4). Welcome to E-stonia. Retrieved from U.S. News & World Report: http://www.usnews.com/opinion/blogs/eric-schnurer/2014/12/04/estonias-e-citizenship-may-mark-the-beginning-of-the-virtual-state

Activities

- Discussion

- What are your experiences with e-government?

- What are some benefits of e-government? What are some drawbacks?

- What are your opinions of e-citizenship?

- What levels of government are best for e-government? Why?

Unit 5: Community Exchange

Unit Overview: The lessons of this unit each have to do with individuals exchanging resources with each-other. In the case of time-banking the resource being exchanged is time while the P2P/sharing economy usually deals with the exchange of services. After understanding the basic ideas of these two concepts, several issues surrounding them will be discussed including trust, community building, and the practicality of implementing technological systems that facilitate these concepts. Students will also get hands-on experience with time-banking by participating in a local time-bank. They will discuss their experiences with this in class.

LESSON: TIMEBANKING

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Understand the definition and basic concepts of timebanking

- Understand co-production and how it compares and contrasts with timebanking

- Experience timebanking first-hand by participating in the local timebank

- Discuss their experiences with timebanking and their opinions of the practice

Readings

- TimeBanks USA. (n.d.). More About Timebanking. Retrieved from http://timebanks.org/more-about-timebanking/

- Stephens, L., & Ryan-Collins, J. (2008, July 16). Co-production. Retrieved from New Economics Foundation : http://www.neweconomics.org/publications/entry/co-production

Activities

- Hands-on assignment

- Timebanking with Happy Valley Time Bank - Students will learn more about time-banking by participating in the local time-bank. They will also meet with the administrator of the time bank and learn more from her about time-banking.

- Discussion

- Discuss your experiences working with Happy Valley Time Bank

- Do you think time-banking apps in their current form are practical? What would you change?

- What is co-production and how does it relate to time-banking?

LESSON: P2P/SHARING ECONOMY

Lesson objectives: Students will

- Understand concepts related to P2P exchange and the sharing economy

- Discuss characteristics of P2P services

- Discuss the role of community in P2P services and the sharing economy

- Debate the role of trust in P2P services and the sharing economy

Readings

- Tanz, J. (2014, April 23). How AirBnB and Lyft Finally Got Americans To Trust Each Other. Retrieved from Wired: http://www.wired.com/2014/04/trust-in-the-share-economy/

- Tufekci, Z., & King, B. (2014, December 7). We Can't Trust Uber. Retrieved from The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/08/opinion/we-cant-trust-uber.html?_r=0

Activities

- Discussion

- Are services like Uber really a P2P economy? What about Lyft? AirBnB?

- What are the differences between these different services?

- Should P2P services focus more on community building? How could they go about doing this?

- These two articles present somewhat contrary view points - that P2P services are increasing trust amongst users but decreasing trust that users can have for service providers. Do you think both, one, or neither of these things are true? Why?