Local Ownership, Exercise of Ownership and Moving from

Passive to Active Entitlement:

A practice-led inquiry on a rural community network

1Computer Science Department, University of

the Western Cape, South Africa.

2School of Art and Design, Coventry

University, United Kingdom.

Email:[email protected],

[email protected], [email protected],

[email protected]

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of ownership, often in constructs such as local ownership, community ownership, and sense of ownership, is garnering critical attention in community informatics (CI) and Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) theory and practice. This interest is motivated less by ownership per se, which at its base resides in feelings of possessiveness towards a target, and more by the way ownership appears to be associated with other key phenomena and processes that can make or break the success of CI or ICT4D interventions, and their capacity to last over time. The local sustainability of CI interventions, for instance, requires enduring, committed and effective action, which are best afforded when local people regard an initiative as their own (Pade et al., 2008). As indicated by several studies (e.g. Ballantyne, 2003; Weeks et al., 2002; Pade et al., 2008) ownership connects with, determines or stands at the basis of empowered action and control, committed local participation, and the drive to engage in capacity building; all of which can uplift a community's capacity to take agency of and engage effectively in the care and management of a CI initiative. What remains unclear, however, is why ownership is such a key link and how it can be measured in a systematic manner. In other words, how can a concept regarded as fuzzy and unclear (Khan and Sharma, 2001:13; Johnson and Wasty 1993: 2) be operationalized and used in systematic measurement?

In this paper, we aim to shed light on local ownership from a double practical and theoretical perspective, and examine its meaning as well as the factors that are bound to influence its development in community-based interventions. The questions we intend to answer are:

How can 'local ownership' be defined in a way that facilitates its investigation in CI practice, and enables at the same time its theoretical examination and relation with other CI key conceptual constructs?

What key factors contribute to fostering local ownership in CI initiatives, taking the case of an externally initiated rural community network?

To answer these questions, the paper reports on a study which assessed the development of local ownership in a rural community network in South Africa and singled out the factors found to delineate the development of a sense of ownership in local people, as well as driving the exercise of ownership towards autonomous local action. Based on a detailed analysis of the development of community ownership in this project, and in constant dialogue with the community informatics and social science literature, the paper makes three key contributions to CI theory and practice, as well as more specifically to future practice in community networks:

- An operational definition of local ownership and a conceptual model which highlights relations to other constructs such as responsibility, power and control and emphasises the role of local ownership in moving from passive to active entitlement towards community assets or CI interventions

- An empirical analysis of the development of local ownership in a community network in rural South Africa, highlighting the critical factors that led to fostering ownership

- An examination and critical discussion of factors that are positively related with the development of ownership, carried out in dialogue with CI scholarship and highlighting the bearing of and relations with other critical constructs in CI research, such as participation, empowerment, and capacity building

These contributions come at a critical stage in community informatics development as a discipline, in which, we argue, a more solid and critical engagement with theory is required to firmly establish its place and the premises for dialogue with other socio-technical disciplines.

2. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

2.1. Local ownership: an interdisciplinary exploration

Ownership is a concept with a committed scholarship in social science research, in particular in the disciplines of psychology, workplace studies, organisational and management studies (e.g., Avey et al., 2009; Holmes, 1967; Pendleton et al., 1998; Pierce et al., 1991, 2003, 2009; van Dyne and Pierce, 2004). In this review, we were interested in a particular facet or type of ownership: the subjective state developed by an individual in relation to a collective, an organisation, a company, or a project. This conceptualisation of ownership has significant advancements in organisational studies, and integrates insights and approaches from sociology, psychology, business and legal studies. In organisational studies, formal ownership is distinguished from psychological ownership. Formal ownership is legalized by formal arrangements and is generally understood to cover 1) the right to possession of some form of share or revenues; 2) the right to exercise influence or control; and 3) the right to information about what is owned (Pierce et al., 1991). Psychological ownership refers to "that state where an individual feels as though the target of ownership or a piece of that target is ''theirs''' (Pierce et al., 2003: 86).

Just as in other social science disciplines, ownership gathereded scholarly attention not only for the importance of the concept per se, but alfo for the way it has been shown to influence subjective attitudes and behaviour, such as job satisfaction and commitment to the organisation (van Dyne and Pierce, 2004). For instance, ownership has been shown to be positively related with self-identity (Kasser and Ryan, 1993) and employee involvement and commitment to a company (Pendleton et al., 1998).

Several models have been proposed in organisational studies for conceptualising the genesis, mechanisms and effects of psychological ownership and its relation to formal ownership. In our study, we draw upon an adaptation and interpretation of the model of psychological ownership advanced by Pierce et al. (2003), used and validated in several empirical studies (e.g. Pierce et al., 2009; van Dyne and Pierce, 2004), and further extended by Avey et al. (2009). The model conceptualizes the roots, mechanisms, and outcomes or effects of psychological ownership. At its core, psychological ownership is treated as a psychological state, a blend of cognition and affect expressing a sense of possession towards a target or object, be it material (such as a house), immaterial (such as an idea) or human (e.g. one's daughter, one's pupil).

The authors identify three roots or motives that act as facilitators for developing psychological ownership:

- Efficacy. By using objects effectively, agents develop a sense of efficacy and effective interaction with the environment, which reinforces the drive for possession.

- Self-identity. The possession of objects, roles or functions supports the definition of an individual's identity, for instance the way a person may identify herself/himself as an antique collector (Avey et al., 2009).

- Having a place and experiencing belonging. Possessing satisfies the human need to belong.

The sense of ownership is reinforced by three routes or mechanisms:

- Control. The more an agent experiences a sense of control over an object, the greater the sense of ownership.

- Intimate knowledge. The more an agent engages and becomes familiar with the target, the greater the feeling of ownership developed.

- Self-investment. An agent is likely to feel that s/he owns that which is created or shaped by herself/himself. Creations or products of one's labour (e.g. ideas, artworks) are equally representations of the self (Durkheim, 1957; Locke, 1690; Pierce et al., 2003).

The dimensions of 'responsibility', 'commitment' or behavioural components such as effective action or performance (central to developmental definitions of ownership) are treated as effects of ownership, or manifestations thereof in the model advanced by Pierce et al. (2003). For instance, it is considered that responsibility or stewardship are likely effects of psychological ownership, as the agent tends to care for and nurture the object possessed (Pierce et al., 2003). Organisational commitment and work performance are likely to be positively influenced by a high sense of employee ownership (Pierce et al., 2009). Avey et al. (2009) expands the model and proposes a multidimensional concept of psychological ownership comprising territoriality, self-efficacy, accountability, sense of place (belongingness) and self-identity.

In community informatics, the concept emerged and gained importance in close relation with practice, in particular depicted as a critical factor conditioning the success or failure of CI or ICT4D initiatives (Pade et al., 2008). Given the focus on practice, the definitions of ownership currently circulated in CI and related ICT4D literatures betray their articulation in specific empirical contexts and a feeble theoretical engagement, so that ownership is defined variably as:

- "processes where local stakeholders take control and responsibility for the design, implementation, and monitoring of an activity." (Ballantyne, 2003)

- "the exercise of control and command over development activities." (Molund 2001: 2)

- "the control over a project or program and commitment to its success." (Weeks et al., 2002)

As this paper seeks to demonstrate, ownership is at the same time clearly distinguished from and related with other constructs such as responsibility, commitment, and control. As well as seeking to contribute an operational definition of local ownership, the paper will clarify the relations between ownership and other important constructs in CI. Some of these constructs have been already approached in previous studies, in particular: ownership is often regarded as closely related with power or control over an initiative (Molund, 2001; Weeks et al., 2002), a foremost factor for the sustainability of interventions (Pade et al., 2008), and mutually reinforced and reinforcing capacity building and community participation in CI initiatives (Idem).

2.2. The Mankosi Community

Mankosi is a traditional rural community in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, composed of 564 households scattered across 30km2 of very hilly land. There is an average of 6 people living in each of them, with over 60% being 15 or older. They live in clusters of several thatched roof and mud-brick rondavels, an occasional tin-roofed rectangular dwelling; adjacent to an animal corral and a garden for subsistence crops. In 2013 the government built pit latrines in their yards. Affluent people use flat-roofed housing to collect rain water; the rest have access to water points on communal land. Most families use open fires to cook, with wood collected from rapidly disappearing indigenous forests; as gas and paraffin is expensive. Electricity in the community is quite scarce, and where available, the service suffers from frequent and prolonged blackouts (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014a). Only 2.1% are connected to the grid, and only 13.5% have a generator, solar or gas (Rey-Moreno et al., 2015b).

People in Mankosi live on roughly 1 USD a day, obtained from government pension grants and migrant family members. Only 13% of the population have completed matriculation (grade 12) or higher. Thus literacy can be problematic, where the capacity to read and write isiXhosa (roughly 70%) is much higher than English (at most 46.7%), with older people reporting the lowest levels (Rey-Moreno et al., 2015b).

Like 36% of South Africa's population, Mankosi inhabitants are governed by a Tribal Authority (TA) comprising a Headman, 12 Sub-headmen and messengers. The Headman and Sub-headmen's homesteads are local administration sites (Bidwell et al., 2013).

An NGO started operating in the area 10 years ago, with headquarters at a backpackers. There is a constant influx of tourists over the year, as there is a public boat launch and a well-known surf break nearby. The NGO has development projects in health, education and environmental sustainability, and has helped create some local businesses in the community targeting tourists, e.g. a restaurant and guided river and hiking trips. Although the NGO was initiated by people from outside the community, it is currently managed by locals.

3. RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1. Initial modelling of the ownership construct

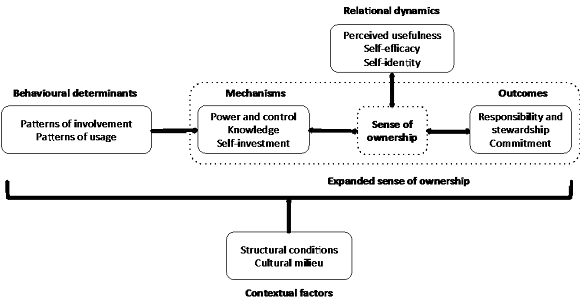

This study was guided by a conceptual model (Fig. 1) based on an adaptation and interpretation of the model of psychological ownership (Pierce et al., 2003, 2009; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004) and its extension in Avey et al. (2009) (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014a). In the same stance, we treat ownership as a psychological construct (a state inclusive of cognition and affect), multidimensional, evolving and dynamic.

The analytical model bears five categories, explained below with reference to the Mankosi community network (which is described in detail in Section 4):

1. Behavioural determinants of ownership. These include patterns of usage (how and to what extent the network is used) and patterns of involvement, referring to types of activities conducted for the development, maintenance and management of the network. The patterns of involvement have been operationalized in relation to the agent's degree of autonomy (autonomous individual, autonomous in group, assisted by external researchers, under the direction of external researchers) for specific project tasks.

2. Mechanisms or direct routes to ownership. This category covers the most important mechanisms for cultivating ownership, which can be treated as direct predictors or indicators of ownership of the entire initiative or parts thereof. Three mechanisms have been identified:

- Power and control refers to the perceived or actual control an agent has over directing the course of events by direct or indirect action and decision-making.

- Knowledge captures degrees of knowing about the project (e.g. its goal, milestones, etc.) and operational knowledge or skills covering certain areas vital for the advancement of the project (e.g. being able to assist maintenance of solar power and energy storage solution).

- Self-investment indicates an attitude towards action by which the agent deeply engages herself/himself, willingly bringing in time, energy or even identity (Pierceet al., 2003). It can also denote a subjective perception of and attitude towards activity outcomes, which are seen and appreciated as fruits of one's creation or labour, or parts of the self (Ibid.).

3. Relational dynamics (relation target-agent). This category captures the pattern of relatedness between the agent and the target, answering the question: what role, function, or need does the target (the network) fulfil or help to fulfil, for the agent? Three components are identified:

- Perceived usefulness: the degree to which the network is perceived to meet collective and/or individual needs and goals of local stakeholders (e.g. helping people save on calls).

- Self-efficacy: the degree to which the agent perceives s/he is able to perform effectively to achieve set goals in relation to or through the mediation of the target.

- Self-identity: the degree to which the agent uses the initiative or a component thereof (e.g. one's role, one's achievements) to define himself/herself or express her/his identity to others (e.g. "When I meet new people, I describe myself as a local researcher for the Mankosi community network") and the associated feelings (e.g. "I am proud of being a local researcher").

4. Sense of ownership. This is the core of the model, and captures the degree to which the network is perceived as one's own, individually and/or collectively. It is important to state that the components within the categories Mechanisms and Outcomes of ownership can be treated as strong predictors or indicators of a sense of ownership (for instance, a high degree of ownership is likely to couple with a high degree of control and high assumed responsibility). While other ICT4D models choose to treat these elements as dimensions of ownership (e.g. ownership as responsibility and control), in here we choose to emphasize the relations of determination among these elements, without denying however that they can be used as indicators of ownership. To mark this distinction, the model designates a core and an expanded sense of ownership.

5. Outcomes or effects of ownership. These are attitudes, states and behaviours developed as a consequence of building a sense of ownership. We focus here on two such constructs, though there can be many others identified.

- Responsibility and stewardship. Responsibility refers to the degree to which an agent feels responsible and accountable for the network and/or for outcomes of one's own work. Stewardship refers to the care and custodianship of resources on behalf of someone. It may equally capture attitudes and behaviours of care and protection over the network, directly or indirectly (e.g. making sure all measures are taken against risks of technical disruptions or thefts; intervening in case of attempted theft).

- Commitment covers the attachment for the initiative and the rationale for maintaining one's involvement in the project (answering the question 'Should I maintain my membership in this organization and why?', Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004).

Finally, contextual factors (Pierce et al., 2003) group those determinants that are likely to have an impact upon the project and people's relating to the project. Factors can be structural, such as the legislative infrastructure (e.g. physical barriers to participation in project activities due to distance; low formalization of property rights), and socio-cultural, such as mores, customs, socialization practices and traditions (e.g. culturally validated hierarchical decision-making patterns; socially constructed collective types of ownership).

RelationsThe model has been built to surface relations between the determinants, mechanisms and outcomes of ownership, as well as the bearing of contextual factors. Two types of relations have been hypothesised:

- One-sided relations of influence and causality (one-sided arrows) hypothesised between on the one hand Behavioural determinants and the Mechanisms of ownership; and between Contextual factors and all constructs pertaining to the Core and Expanded sense of ownership.

- Mutual determination (double sided arrows) between the Core and the Expanded sense of ownership - the latter corresponding to its mechanisms (e.g. a high degree of control influences positively a high sense of ownership, while a high degree of possession in turns determines a stronger feeling of control) and its outcomes (e.g. high sense of ownership determines high responsibility, and also the more one feels responsible for the network, the more s/he feels it as her own).

In addition, it has been hypothesized that the Mechanisms category acts as mediator for Behavioural determinants. We proposed that behavioural determinants on their own cannot be used as factors for increased ownership, if not through the mediation of mechanisms (for instance, one may make heavy use of services, or have been involved in many project tasks, but s/he is not likely to develop a sense of ownership unless s/he has sufficient control, knowledge and/or self-investment).

Contextual factors can act as barriers or facilitators for developing ownership (e.g. hierarchical model of decision-making can limit one's sense of ownership by excluding her from decision-making), or can drive orientation towards certain forms of ownership, such as individual or collective.

3.2. Data Generation and Analysis

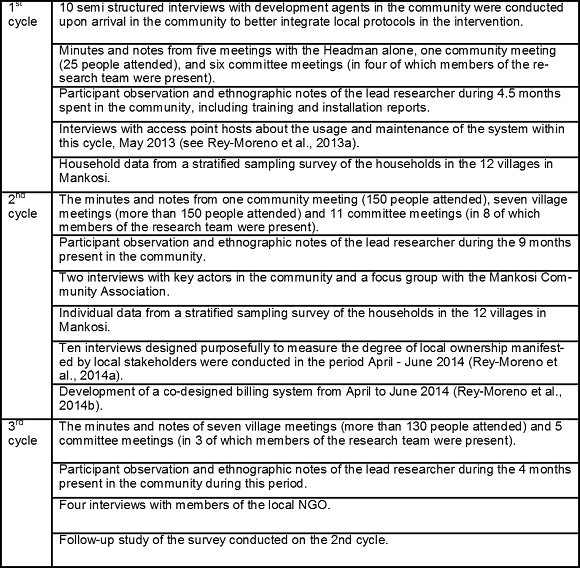

The data used in this paper has been generated by means of Ethnographic Action Research (EAR) (Tacchi et al., 2003). The EAR process, and particularly its core cycle Plan-Do-Observe-Reflect, enabled the configuration of three broad initiative cycles, as follows:

- First Cycle (April 2012 - June 2013). Partnership and free will.

- Second Cycle (July 2013 - July 2014). Establishing trust, ownership, financial and legal resources, and tools.

- Third Cycle (August 2014 - On-going). Providing services legally and learning from it.

EAR enabled data generation all throughout the initiative, through a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods, further outlined in Table 1 below for each of the cycles.

The data generated was analysed and interpreted in waves, to enable fast assessment and inform the refinement of the initiative design and corrective actions. At the same time, a growing data corpus was aggregated, which was used for more elaborate inquiries. For the purpose of the present study, focused on assessing the development of ownership, the analysis was done initially on a core corpus of 10 interviews specifically designed to look at the development of ownership and relate it with stakeholders' participation in the initiative, following the model outlined in Figure 1 above. Based on this analysis, a series of themes have been elicited that outlined the type of ownership developed (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014a) and the relations with other key components in the model, including the mechanisms of ownership (such as power and control) and the patterns of relatedness with the network (such as self-efficacy and self-investment). In a second stage, these themes have been probed with the larger data corpus, particularly looking at: 1) the evolution of the initiative and the gradual gain in independent community action, on a timeline; and 2) the field notes and reflections of the lead external researcher who has been involved in all stages of the initiative.

4. OWNERSHIP BUILDING IN THE MANKOSI COMMUNITY NETWORK: THE PROCESS

This section describes the iterative design and development of the Mankosi Community Network (CN), and highlights the evolution of the relationship between the research team and the Mankosi community.

4.1. First Cycle (April 2012 - June 2013) Partnership and free will

Setting goals and sanctioning commitments

Early visits to Mankosi were meant to assess the possibility of using wireless mesh networks operated locally to reduce communication costs (Rey-Moreno et al., 2013b). Previous research showed that rural costs were high compared to their urban counterparts (Bidwell et al., 2011). The research team in the field included two people. The first spoke both English and isiXhosa (the local language) fluently and was a postgraduate student in Computer Science. His role was important for bridging communication between academic researchers and the community. The second was a foreign researcher with experience in rural community informatics in several countries.

Interviews were held with other development agents in the community, which, when put together with the results of previous research in the area by the group and knowledge of the potential of technology, yielded the idea of using public phones on a mesh network to provide cheaper calls within the community. We then held a meeting with the Headman, following an acknowledged protocol for anyone wanting to start a project in a rural Xhosa community (Pade et al., 2008). This meeting covered the idea of local calls, the intervention's pros and cons, and potential benefits to the community. The Headman appreciated the intervention's benefits, and called a larger meeting with sub-headmen, messengers, advisors, and other people interested in community development. The project idea was presented again to the larger TA, and after receiving positive feedback, the research group was granted permission to work in the community.

Those meetings also delineated mutual commitments. The research team agreed to provide eight solar powered nodes (that ended up being ten) to provide voice services throughout the community; and the provision of training for their installation and management. The TA committed to choose the households in to which to place the mesh nodes, and to decide the mechanisms and pricing for calls in order to achieve financial sustainability. Furthermore, a TA-endorsed team was expected to manage and operate the network. The research team was given permission to monitor the process for research purposes. The local NGO also joined the partnership by allowing the installation of a data-collection server laptop on their premises. They also agreed to provide access to the NGO's tools and vehicles for local transport.

The TA participated actively in the physical design of the network, identifying households that satisfied technical, social and security needs for the project (Rey-Moreno et al., 2013b). It is worth noting that the TA's node location choices met these needs while simultaneously satisfying local politics, e.g. ten nodes were located in ten of the twelve villages that make up the community.

Working with local researchers and technicians

Based on success with previous projects (Bidwell et al., 2013), Local Research Assistants (LRAs) were identified to bridge linguistic and cultural gaps between the research group and the community. A local-born young man played a leading role. He had been involved in previous projects and enjoyed respect amongst local stakeholders. The LRAs were hired to collect and interpret data via questionnaires and interviews. The fact that there were funds to hire LRA's but not for the project itself, e.g. hiring people to operate the phones, created some tension. However, careful explanation of roles and the empowerment nature of the project unlocked a situation where there was a potential for blockage. It is worth noting that all data collection activities were used for dissemination purposes as well, e.g. informing people that the project belonged to Mankosi.

To increase the sense of ownership, local technicians were expected to install the network. Thus, the TA called for and appointed members of the community who were interested to be trained and assist with installation. We offered transportation and food during the proceedings, albeit no remuneration. The response to the general call was encouraging and a team of 4-5 people attended every day over a span of two months. In the initial training sessions, theory was followed by hands-on practical exercises, e.g. basics of electricity followed by dimensioning and installing a solar system. After a sample was constructed by a trainer, trainees constructed additional units by themselves under a watchful eye.

Training was also provided to end users, by the installation team. At least one member from each homestead attended. The training covered both practical maintenance tasks and in-depth detail about how things work, especially the electrical power. This included concepts regarding security and consumption of battery power. All training was given in the local language. If the trainers were English-speaking, then an LRA translated to and from isiXhosa.

The solar system was modular, allowing each piece to be disconnected for independent repair, e.g. a panel with a user console on top and the wiring beneath (Rey-Moreno et al., 2013a). The rationale behind the design was explained to trainees in depth, including how to change fuses and replace them with bigger ones, and the consequences of doing so; to encourage end users to learn about solar and electricity basics, and to allow them to gain confidence while facilitating localized maintenance. In practise, most maintenance has been done by the lead local researcher, as he wanted to make sure that he understood the different sources of failures before allowing others to experiment.

Involvement of local people during installation was expected to increase confidence and provide sufficient technical knowledge to reduce outside dependency. To take this approach further, the local support team was encouraged to replace antennae independently. After the installation of the antennae and some tweaking on the software done with the remote assistance, the local team made the network fully operational by themselves.

Considering options for financial sustainability

From the beginning, a strong emphasis was put on the need to generate some form of income to maintain the network. Initially, local people suggested charging for internal calls, contrary to our idea of a Skype model where local calls are free. The solar systems were intentionally over-dimensioned to allow users to charge mobile phones. They considered this an additional revenue stream. This extra energy generation was also intended to allow users to plug in other devices such as a light and/or radio, and thus contribute to a sense of project ownership and encourage care of the system.

Collecting money from charging mobile phones raised questions for some locals, as they considered the system (including the chargers) an outsider intervention meant to provide free services to all. Following a meeting organised several months after the stations had been operational, a fee and a mechanism to collect money for charging mobile phones were agreed upon. Additionally, they discussed the use of the public phones, which were being used only for TA-related purposes. This discussion surfaced tensions and misunderstandings, as well as a general lack of information with respect to the network and its usage. According to someone hosting a phone:

"People in our villages do not use the mesh network because I think we didn't spread or introduce properly the mesh potato network in our villages and people do not pay that much attention to the mesh network because it is just working only to Mankosi".

Consequently, it was decided to allow people to use the public phones for free yet pay to charge a mobile phone. Local management of the fee collection did not immediately yield fruitful results. Following discussions between the Headman and the researchers, a meeting was organised to clarify several misunderstandings, particularly the benefits expected by the people hosting the points and collecting money for charging phones. It become clear that a substantial challenge was the blockage caused by a series of expectations, partly conditioned by previous projects in the community, and partly by the emulation of local hierarchical structure. For example, as in previous projects, local people were hired for various activities. It was expected that the hosts of access points would also be hired and were entitled to keep the money for charging phones. The meeting was an occasion to discuss again community benefits, as agreed in the initial partnership, and reflect on how local people could organize themselves to manage the process properly. They proposed to charge 3 ZAR per phone and agreed to meet in a month to check on performance, before discussing the idea with the community. The use of internal calls was also discussed. It became clear that they were not many such calls, because they could only call between villages. In their opinion, the project would be much more useful if it enabled people to call mobile phones, i.e. call break out. The research team confirmed this possibility, pointing out that for this to happen, it was necessary that money be collected consistently to pay for an Internet connection.

4.2. Second Cycle (June 2013 - July 2014) Establishing trust, ownership, financial and legal resources, and tools

This cycle started with a meeting held on July 2nd 2013, where a committee composed of a representative from each household hosting an access point was confirmed and given the responsibility for making break out calls a reality. It was decided to create a completely new committee in order to start afresh, avoiding distrust associated with existing development agents in the community.

Additionally, village meetings were conducted by the lead local researcher, with presence from the research team, to give the opportunity to those community members not able to attend the community meeting to learn about the project and the agreements reached.

Building local control and accountability mechanisms

A new engagement protocol was considered for this cycle. Previously, the research team wanted to be part of all discussions, and translation was necessary. In this cycle, the meetings were prepared in advance by the lead LRA, and the role of the external researcher became more that of a consultant. In addition, meetings were conducted on local terms, using local language and concepts. For example, when concepts like Voice over IP and Internet bandwidth were introduced, examples were used that committee members could relate to day-to-day experiences. Additionally, discussions were limited to a smaller number of topics so as to not overload meetings.

Attendees started to make decisions about what to do with the money collected and how to solve problems. More than 10,000 ZAR was collected during this period. At the beginning of every meeting, each member handed over the money collected in his/her household since the last meeting. Logbooks were used to keep track of how many phones had been charged. This mechanism was stressed to users such that they should get their name written every time they charged a phone to prevent abuse and provide accountability. The amount brought by each committee member was often higher than the one reflected on the logbooks. Even when a 100 ZAR contribution was established as a minimum to make sure no one cheated, some members brought more. This included one of the two members exonerated from this quota, as their houses were in areas with other charging options, and so were not reaching the minimum. The money brought by each member was counted, and both the total amount collected in the household and by the committee that month were written back in the logbook. The same transparent approach was taken with expenses, so that all receipts coming from agreed purchases were shown.

Setting workflows and protocols for local decision-making

More people attended meetings than in the previous cycle. To foster flexibility and allow committee members to run private errands, it was possible to postpone meetings where a minimum number of attendees could not be confirmed; and when lead participants were unavailable, other family members could attend in their place. Important agreements made earlier were repeated in subsequent meetings, to ensure everybody was on the same page. Local people started taking a more prominent role, and it was often committee members leading the discussion rather than the lead LRA. In some cases agreements were reopened and introduced delay, yet this approach reinforced the autonomy of the members having taken the decision.

Decisions were always made collectively (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014a). For instance, it was realized that there might be some external interest, so the committee was asked for permission to talk about the project to the press, and when possible to invite an LRA to do the talking, e.g. during the Information and Communication Technologies and Development conference in December 2013 held in Cape Town, and the Department of Science and Technology budget vote in July 2014. The outside interest in the project and the prominent part played by one of their peers, the lead LRA, was an additional boost for their self-confidence, as they want to be a good example for others to follow.

The changes in the meeting process were not devoid of challenges. People were not used to making decisions, and in many instances they still turned to the research team to ask for authorization for a given decision, or directly asked them to make the decision on their behalf. The outside researcher was however firm in insisting on non-interference, marking his outsider, consultative role with the phrase "Abalungu out", meaning there were no white people interfering in the process, and that he was merely an observer in their meetings. This approach seems to have contributed greatly to independent and confident action, which was proven during the process of lodging the cooperative. When it was suggested that they could receive help from a local expert or from the Local Municipality, they rejected the offer proving to themselves they could do it alone.

Milestones within the cycle and official certification

At this stage, many milestones initially set for the project were met: installation of lights in households, establishment of the cooperative, application for license exemption, a bank account for the cooperative, a billing system for break out calls and realising break out with an Internet gateway.

The installation of lighting was part of the demands by committee members as compensation for work done within the project. Two LED lights fed by the solar system were installed in 7 of 8 houses. Installation was done by two locals trained by the research team, and both their work and the materials were paid for by each of the households. As another form of compensation, they were allowed to charge mobile phones for free. Both forms of compensation were approved in a community meeting.

Lodging cooperative and license applications was delegated to the lead LRA and the research team, including preparation, paperwork and coordination of logistics. Although this process was led by a member of the research team, the decisions and the challenges were shared in the meetings. The official cooperative registration was celebrated with rounds of applause. The same happened with the opening of the bank account, a process that was completely led and completed by locals. From that point, the initial committee members were recognized as board members of an officially registered cooperative.

Technical implementation of the break out calls and the billing system

The billing system was co-designed with the community, and more concretely with the cooperative board members and their families (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014b). This ensured that: a) the billing system met their needs, b) they understood how it worked and were able to operate it, and c) they trusted the money collection system. During co-design workshops, emphasis was given that both Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Voice over IP (VoIP) providers would request payment for any use of their services, so special attention was paid to preventing abuse of the system. The implementation was meant to reduce complexity, and even older people managed to complete the training successfully. When it was expressed that they might forget about the process with a lack of practice, one of the members said that this was good because it would force them to stay awake and committed.

The implementation of the billing system and the VoIP architecture to allow and bill break out calls was done entirely by the research group. This included the discussion with VoIP providers to get the cheapest per minute prices, and to determine the most suitable technology for the Internet Gateway. In all cases, the options, and their consequences, were discussed in cooperative meetings, and the providers (the prices at which they buy the minutes) and the prices for the service (the price for which they sell the minutes) were decided by the cooperative board members. It was decided that once the training for the billing system was done in all households hosting the system, and the gateway installed, they would proceed to offer the service.

4.3. Third Cycle (August 2014 - On-going) Providing services legally and learning from it

This cycle started the moment the cooperative was able to provide break out calls; from July 14th 2014.

Towards independent operation

The meeting protocol was changed again, following the proposal of the lead LRA who proposed that cooperative members lead the meetings, and call on the community to attend. This resulted in four cooperative board members (plus one in whose village the meeting was taking place) being involved in the communication campaign.

That was the first of a set of logistic tasks that local people have carried out more independently in this cycle. Additionally, they acted independently to open a bank account (see previous cycle), activate Internet banking, and obtain a Tax Clearance certificate. They also deposited money several times into the account. Amounts were communicated several times during meetings, and then the deposit slip shown during subsequent meetings.

They also performed other tasks to foster the use of the service, especially after the concession of the license by ICASA in September 2014. This included posters touting the availability and cost of the new service and participation in community meetings to disseminate further information on the new service offered.

Solving issues and tensions

This independent action came with its own tensions and problems, which provided further motivation and encouragement to act autonomously, as the following example shows. One station owner decided to leave the project, and therefore his station needed relocation. This station was problematic from the beginning of the project, as it was unusually close to houses with electricity. It was therefore given a waiver to bring in the 100 ZAR agreed. In time it became obvious that the problem was that the station was installed in the room of an elder's oldest son, outside the control of the rest of the household. He was charging phones for his friends, either for free or keeping the money. The situation was confronted by the lead LRA and other cooperative members, who raised concerns about abuse of the system. The elder asked the cooperative to remove the station from the house rather than him having to pay back the abuses of his children. The station was immediately stored in another board member's house. A community meeting then decided that the station would be relocated to a house in one of the villages that did not yet have a station.

A different type of solution was opted for in another case, when the revenues continued to be low from a house situated centrally, and therefore able to serve many people charging phones. A special meeting was called to tackle this issue and it was decided that any outstanding amount was going to be recorded in the operator's logbook, so anyone could see, and he was going to be constantly reminded of paying his debt. He agreed, and has slowly balanced his account. However, in the last meeting, discussions revealed that the problem had deeper roots, as the house owner manifested his belief of being entitled to payment for the services provided, especially since he had been appointed as a host without his express agreement.

Solving matters locally was considered as important as managing the network with care and transparency, serving community rather than personal goals, and providing an example to all in the community. In a discussion about using university funds to provide more specialized training to some youth members of the community so as to engage them more in the project, the lead local researcher said:

"I don't think that will give them a good idea of the project. I'm always worried about the image acts will do, misunderstandings, etc. They may think there is money to do everything for free, and it's not the case."

Spill-over effects and future plans

The public service nature of the project goes beyond the telecommunications cooperative, as opportunities are opened to the cooperative for other projects. For instance, when a partnership with an innovation incubator was discussed to receive marketing training in isiXhosa, the local people asked if it could include other businesses in the community. This partnership has not materialized yet, however, it is interesting to observe how much effort they are putting into it. If the interest of national and international researchers already motivated them to perform better, the lead LRA is convinced that people would be further motivated and proud if other Xhosa people from a big town came to learn about the project.

Marketing training for the cooperative members seems a pertinent next step. Despite the effort that went into offering cheaper break out calls, they have not managed to change local people's habits, who prefer to make cellular calls despite its expense. Thus they have asked the research team to study the feasibility to offer the service to mobile phones. This starts a new phase of the project. This might be the first of other services that could be provided by the existing infrastructure, and marketing training could be a good way to leverage them.

5. DISCUSSION

This section provides a critical examination of the process of fostering ownership in the Mankosi community network, along two axes: an outline of different spheres of ownership, and a delineation of key drivers and processes contributing to the development of local ownership.

5.1. Spheres of ownership

We analysed ownership as a subjective state, drawing on direct questions posed to a series of local stakeholders, through in-depth interviews, and probed relations between the core sense of ownership and the constructs hypothesised to be part of an expanded sense of ownership (mechanisms such as power and knowledge and outcomes such as responsibility). Of these, it was found that respondents tended to associate ownership mostly with one of the mechanisms - power and control. Respondents explained their own, others' or the community's ownership of the network by pointing to their power to decide over inherent matters and to control the project advancement. Furthermore, associations between ownership and responsibility were proven, for instance: "We are looking after it, it ours, and we are taking full responsibility of it." (Board member and host of an access point)

Power and responsibility were used by people as indicators or proxies to explain their sense of ownership (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014). However, ultimately ownership was found to be clearly distinguished from these constructs as well. The conceptual essence of ownership resides in a sense of possessiveness, while constructs such as power or responsibility were used to reveal the motivational bases for a sense of ownership, especially when prompted to justify their feelings of possession for the network.

The sense of collective ownership prevailed over manifestations of personal ownership of the community network (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014). Personal ownership was restricted to limited areas of the project or tasks. For instance, people were aware that their ownership of network equipment was only a form by which something that belonged to the community was entrusted to them for safekeeping. As the case of the person stepping out of the cooperative showcased, a station could change hands and still belong to the community. This differs from a more common understanding of community networks, where each participant "owns the part of infrastructure it has contributed" (Baig et al. 2015).

While collective ownership of the network was agreed upon unanimously, the power to manage and maintain the network was entrusted with, i.e. delegated to, a selected group of people, who were board members of the cooperative. The mandate given from the community to board members was replicated within the cooperative, where a handful of people were delegated with the responsibility of exercising the ownership on behalf of the others based on their skills and their commitment (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014). The people entrusted with the management of the network, who actively exercised power, derived a unique sense of ownership.

Although the qualitative study could not lead to definitive measurements, it appeared that the greater the exercise of power and involvement in the project, the stronger the sense of ownership, and with this, the greater commitment to its success. For example: "I have been through it from the beginning so it is like a son that is growing on me." (Board member and host of an access point). Whereas from the perspective of the larger community who delegated power, delegating the exercise of ownership implied as well a transfer of responsibility to the most capable and knowledgeable of their members, who were held accountable for the success of the network. "The board of members of the cooperative [should be responsible], because they said that they are the one (sic) that who were going to drive it into success." This transfer still retained an element of collective responsibility, entrusted with the community as a whole: "I believe that as people of Mankosi we should work together and maintain the existing project for the future. If that (failure) can happen, for me it will mean that we have failed to work together to develop our community." (Board member and host of an access point).

Another layer of collective ownership focused on the relation with the external team of researchers. Due to the trust and harmonious collaboration between the board members and the external team, the exercise of ownership could be partially delegated to the latter without jeopardizing the local sense of ownership. This resonates with Kaplan's idea of the possibility of the external team being considered as part of the community (Kaplan, 1996).

5.2. Fostering collective ownership: key drivers and processes

We also looked at the gradual development and exercise of local ownership as manifested through practical decision-making and action, and in relation to this we examined the factors that appeared to significantly drive it or be related to it. Based on this analysis, we acknowledge that the development of ownership is a highly specific, locally-bound process, likely to grow and expand following local ways of being, social hierarchies, and emulating local channels of communication and interaction. The process is, however, not controlled fully on local terms, nor shaped purely by local structures. An external intervention is bound to put its mark, especially if it is enduring and if it delivers on its promises, so that a community starts to benefit from its results. Ownership grows and is shaped in a space configured at the encounter between the local environment and the elements of outside intervention, and in so doing it creates its own, hybrid ecology. This ecology comprises and is dynamically configured by a complex and evolving set of factors, actors and processes. Guided by the initial model of ownership (Fig. 1) we encompassed a series of processes and factors to take into account, focusing on the clusters evidenced in the model as conducive to or impacting upon ownership (behavioural determinants, mechanisms, relational dynamics, and the bearing of the local context). The relations between ownership and what we consider to be outcomes or effects of ownership (responsibility and commitment), are treated in-depth in a prior publication (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014). Herein we focus on the factors that foster collective ownership.

The bearing of the local context (Emulating local structures and articulating new ones)

In the Mankosi community network, the development of ownership was a process that unfolded gradually, highly influenced by the local structures and environment, but also arriving to challenge these. At the beginning, the exercise of ownership followed existing power structures (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014). As the project progressed, alternative patterns started to emerge and then crystallise. Rather than contributing to retain power for the powerful, the project appeared to enable the emergence of local cells for decision making and taking action, based on capacity and commitment. This process was not without tensions. Although the role of the youth was acknowledged as pivotal due to their skills, when the youth were present in the meetings, their contribution was minimal. "(W)e'll ask when your mother/father is here" was a typical phrase. On the other hand, the development of a sense of ownership may challenge pre-existing local ways of thinking and doing. As a member of the board explained, "I didn't know that you could still getting a little bit of money without having to go outside of the community to work hard. Just slowly, talking to people to set up the rules getting a bit of money, starting a business that can help people in the future locally."

When participation matters

During the initial stages of analysing ownership, we were aware of the importance of local participation, as amply argued in the CI literature (see for instance Pade et al., 2008). Our first hypothesis was that participation would be positively related with the development of ownership to a greater extent if participation (patterns of involvement) would be doubled by the three mechanisms - exercise of power, knowledge, and self-investment (see Fig. 1). Participation in a position of power, for instance, was thought to have a higher likelihood to influence the development of ownership. The qualitative analysis done did not enable us to map precisely the extent to which these three factors determined patterns of relatedness between participation and ownership building. Yet, it was apparent that expressions of ownership displayed differences in relation to the role one held in the project and the type of involvement associated. Of the three mechanisms - power, knowledge and self-investment - the ones appearing to influence ownership development and its outcomes (responsibility, commitment) most strongly were power and knowledge. Moreover, people whose knowledge was perceived to be greater were deemed by peers as most fit to take decisions and act on behalf of others.

Knowledge, power, and empowerment

Capacity building and empowered action and control are all factors linked to ownership building and the exercise of ownership in CI and community development literature. In the Mankosi community network, the most important factor positively related to the manifestation of a sense of ownership was local empowerment. It was found that the more local people felt empowered to take independent action, the more they felt entitled to the community network and acknowledged that it belonged to them. In the project's early days, people were reluctant to decide and take autonomous action, as they over-relied on external expertise (for instance, they expected to be paid to continue operating the network). This reluctance to exercise control over the course of events manifested in many other development projects in the community and might be related to the historical process of disempowerment that South African rural communities have been subjected to both during pre and post-apartheid periods (Lyon et al., 2001). Empowerment proved to be more important than the knowledge or capacity built, as it acted as a driver for people to consciously and actively seek to garner the know-how needed to perform. In the latter stages, for instance, it was found that people had forgotten the knowledge imparted in the first, network setup, cycle. Yet, this was not a setback, as people were motivated to engage in continuous training. In the long term, however, people appeared to be aware that knowledge and capability to manage the network were required for becoming the only owners of the network and end the reliance on the external team (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014).

Building self-efficacy and self-identity

These were two of the most elusive concepts, yet the later developments of the project, especially during the third cycle, proved that self-efficacy and self-identity were some of the most important factors positively related to the development and exercise of ownership. During early stages, self-efficacy was encouraged by involving people in the setup of the network, so that every landmark in the project was perceived as an achievement afforded by community action, rather than purely a result of external intervention. Self-identity, on the other hand, was cultivated indirectly, by giving local people reasons to take pride and joy in the external recognition of the initiative. Later, such occasions were created through local agency. When outside parties demonstrated interest in the project, having a local researcher act as interface and representative of the community was a further reason of pride and contributed to increasing both self-efficacy and self-identity. Finally, these two states were manifested when people took autonomous action during the certification activities and in all encounters with administration bodies and other institutions, in which they acted as community representatives.Perceived usefulness

This was initially reckoned to be a key condition for people to feel inclined towards ownership (i.e. I want it to be mine because it is useful), proved to have a more complex role. Researchers later learned that the project was not fully understood at the onset, and that its benefits were not readily apparent. Merely acknowledging usefulness was in itself a development, the result of a process, and required knowledge of the project, exposure to its outcomes, and awareness of its future developments. When the project was seen as beneficial on these terms, positive spill-over effects into ownership outcomes (particularly commitment), were noticed. For example: "I think that now that everyone is committed to the project at this stage, everyone wants to use it for a good thing. Because there are plans, like with the school, the maintenance (that they will pay for it), the bank account... The plans are there to use the money for every effective stuff." (Lead local researcher). It is interesting to note here that there was also a strong sense of perceived usefulness in collective terms.

6. LOCAL OWNERSHIP: A DEFINITION AND CONCEPTUAL MODEL

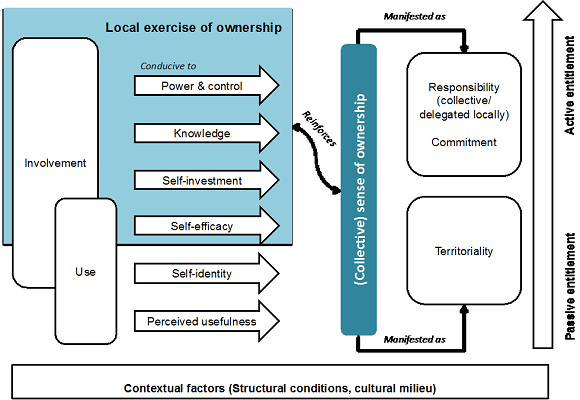

The empirical analysis was used to scope and shape the characteristic features of ownership that can be developed around a technology intervention in a local community. It also served to better probe the constructs and relations initially hypothesised in the model of ownership illustrated in Figure 1. On this basis, an operational definition of ownership and an analytical model for shedding light on the development of ownership, and the different forms it may take, are provided below.

6.1. Definition

Local ownership is defined with reference to a local community or a closely knit group, and a target of ownership that requires active care if it is to provide benefits and usefulness for the community/group (e.g. a technology project, a community network, a cooperative). In this sense, local ownership is devised as a construct that bears a dual cognitive-affective and behavioural dimension, comprising a (collective) sense of ownership and the exercise of ownership.

(Collective) sense of ownership refers to a psychological state comprising beliefs and feelings of (collective) possessiveness and entitlement towards a target. This state is manifested by individual community members, and can blend elements of individual possessiveness (It belongs to me) and collective possessiveness (It belongs to us). In the empirical study discussed in the previous sections, a collective sense of ownership prevailed over individual ownership. Yet, this can be attributed to the existence of a strong collective ethos characteristic of Mankosi (Rey-Moreno et al., 2014), which may not be manifest in other contexts. The likelihood is that a great variety in expressing blends of individual and collective sense of ownership could be demonstrated by individual actors and communities in situated cases.

Exercise of ownership comprises decision-making and activities that can range from strategic planning to hands-on actions that serve to run, manage, or care for the target in ways that ensure its continuity and/or maximize its usefulness for the community or individual members. The exercise of ownership can be enacted locally (either collectively or through representative members), entrusted to/assumed by other parties, or take mixed forms. The case of Mankosi is an example of a mixed exercise of ownership, with a local component (a board of members were given the power to decide and act on behalf of the community) and an outsourced component (undertaken by an external research team).

As a blended construct, local ownership can take manifold forms depending on different nuances acquired by either the sense or the exercise of ownership. For instance, full local ownership implies that a (collective) sense of ownership has been developed, and that ownership is exercised as well locally in an autonomous manner. Our interest is to understand what forms of local ownership are significant in community informatics projects, and how they can be cultivated. To this purpose, the following section introduces a model that relates different manifestations of ownership with a scale from passive to active entitlement.

6.2. Conceptual model

Premises

As any conceptual model, the one proposed below for the development of local ownership resides on both a take of perspective and a simplification or reduction of reality. The perspective employed seeks to evidence how the development of local ownership is associated with taking steps from passive to active entitlement, with a particular interest in shedding light on the way external interventions are received in local communities.

The model focuses on the community as the main unit of analysis, the intent being to understand how local ownership is manifested and can be developed at a collective level. This implies that the analysis is not geared towards finding replicated patterns in individual members, but rather complementarity and consistency in the development of a sense of ownership and the exercise of ownership, either collectively or through representative members. However, the collective dimension does not preclude focused analysis based on multiple units of observation, including individual members and relations between them.

Overview and components

The model interprets the development of local ownership in relation to the likelihood of bringing about passive or active entitlement. In both constructs, entitlement denotes that the community has developed a sense of owning the target and is entitled to reap its benefits. Passive entitlement implies that the agency of an external party is required to make the target work and provide benefits for the community (e.g. educational facilities managed entirely by an external agency), analogously to a service, product or resource that requires minimum or no action on behalf of the community and is self-sustaining (e.g. local woods or rivers). Active entitlement denotes willingness and capacity to manage/run or make the target work for locally defined goals in locally defined terms. In other words, active entitlement means 'owning the next decision', and being prepared and able to act upon it.

To understand under what conditions a sense of ownership can be associated positively or conducive to either passive or active entitlement, we focus attention on a series of pathways (or routes, mechanisms) for the development of ownership, starting from two behavioural drivers: involvement and use (as described in section 3.1). From the two behavioural drivers, six main pathways for developing a sense of ownership are identified. These are associated with involvement (power and control, knowledge, self-investment), use (perceived usefulness), or both (self-efficacy, self-identity). The constructs are as defined in section 3.1, where these were marked as either mechanisms for the development of ownership, or constructs characterising the relation between the agent and the target.

In Figure 2, these are treated like pathways conducive to different forms of local ownership, by reinforcing either or both the exercise of ownership or the sense of ownership. In particular, the constructs power and control, knowledge, self-investment, and self-efficacy are regarded as conditions for the exercise of ownership and essential components in cultivating local ownership that eventually leads to Active entitlement. For this to be reached, it is necessary that the community as a whole or key members in the community will have developed the will and capacity to manage and care for the target. The sense of ownership developed through these routes has a higher likelihood to take forms close to responsibility and commitment, either collectively, or through representative members. Mankosi is an example where collective responsibility for the network was developed, in association with delegated forms of responsibility for those members that were actively involved in its management and maintenance. The case of Mankosi also displays some unique features, as the exercise of ownership blended local and external agency.

Forms of local ownership with a more feeble or no presence of the exercise of local ownership can be developed, which lead to Passive entitlement, where the community does not support or manage actively the target that satisfies a need. For instance, a sense of ownership can be developed in time from a high appreciation of usefulness and/or by identifying with the target, without engaging actively in its management or care. Territoriality is an example of the way ownership may be manifested by taking these routes, referring to attitudes and behaviour of protection for the target and their rights over it or defence when an external agency jeopardises it.

In sum, a feeble or no presence of the exercise of ownership mediated by the four pathways - - power and control, knowledge, self-investment, and self-efficacy - is likely to lead to a sense of passive entitlement. On the contrary, active exercise of ownership is likely to lead to a sense of active entitlement, where the community has developed the resources (behavioural and psychological) to make the target work for their own defined ends in their own defined terms.

Model use and limits

The model does not attempt to exhaust the manifold forms of local ownership or sense of ownership that can be developed in a community, but point to the essential coordinates that are likely to be conducive to such forms that are connected either with active or passive entitlement. It has been specifically devised to shed light on 1) the elements to be taken into account for contributing to developing forms of ownership that relate to community autonomous action and management of interventions; and 2) the bearing of ownership in explaining such processes as community participation, local action, or sustainability in the evaluation stages of a project. To this purpose, the model dwells on a simplification of complex processes. It is intended as a tool for capturing snapshots in highly dynamic processes, without exhausting their intricacy. Limits are associated as well with its being tested in a unique empirical context and against extant literature. Testing in other empirical contexts is necessary for probing, in particular, the role of the local context in determining peculiar forms of ownership and the processes leading to their development.

7. CONCLUSION

This paper provided a practice-led inquiry into the development of local ownership in an externally-initiated community network, and consequently examined its scope and the factors that went along with this development. This analysis contributed to developing a definition of local ownership and a model that sheds light on how different forms of ownership can be developed in community settings, which are conducive to either passive or active entitlement towards the target of ownership. One of the takeaway messages from our paper is that ownership is a critical element to take into account when looking at how a community may receive, appropriate, take action within, and eventually sustain externally initiated interventions. At the same time, as the model proposed highlights, not all forms of ownership that can be developed around CI interventions are necessarily conducive to local commitment and readiness to sustain such initiatives autonomously. The link between ownership and sustainability, which is one of the most important in CI scholarship, appears to be conditioned by the forms that local ownership can take, which depend on the mechanisms by which they have been developed. The likelihood for ownership to lead to sustainable local action is higher if local people are actively involved in the exercise of ownership, for instance if they are involved in positions of power, exercise control, and garner enough knowledge around the initiative to contribute effectively to its management.

A detailed analysis and interpretation of the manifestations and process of ownership development in the Mankosi community network provided an exemplification and illustration of the theoretical claims advanced. While the conceptual model we contributed puts forward a reduction of complex processes, the case of the Mankosi network illustrates the rich and dynamic ecology in which local ownership develops, a hybrid ecology created during the intervention and nurtured by a variety of factors, stakeholders and processes pertaining to the local context, external, or born in the interaction among the two. In this ecology, ownership manifests, in a first instance, as a state, a feeling, a sense which can be either individual, or shared. In the case of the community network we analysed, collective, rather than individual ownership prevailed: the network was perceived as belonging to the community. Second, the case proved that for local ownership to take effect and be conducive to an active sense of entitlement for the network, there is a need for the sense of ownership to be complemented by active local involvement in its exercise.