Bridging the Digital Divide in Dunn County, Wisconsin: A Case Study of NPO use of ICT

- AmeriCorps VISTA Leader: Alaska Network on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, Juneau, Alaska USA E-mail: [email protected]

- Assistant Professor of Information and Communications Technology at the University of Wisconsin-Stou, Menomonie, WI 54751 USA E-mail: [email protected]

- Assistant Director, Memorial Student Center; supervisor, Ally Initiatives for Civil Rights & Civic Responsibility, UW-Stout, Menomonie, Wisconsin 54751 USA E-mail: [email protected]

1. Introduction

As the cost of computers has decreased and availability of high-speed Internet has increased, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has become commonplace in everyday life. Workplace trends in the private sector in more developed countries have shifted, making ICT an integral part of promoting a successful enterprise. However, while the private sector has recognized the need for innovation in business practices, the nonprofit sector in the United States has not been as quick to adapt. Today, large national organizations have embraced ICT as a new means of achieving their visions; small nonprofit organizations (NPOs), however, have not been able to make the changes they need to survive amidst reductions in federal and other grant funding and human resources (Voluntary Sector Initiative, 2002).

Small nonprofit organizations face a number of challenges that impede sustainable digital literacy learning. Many agencies operate with few full-time staff members, making volunteers and temporary help from service-learners essential to their survival. Economic recession has imposed additional constraints. NPOs are now facing a larger number of clients seeking assistance. With increasing caseloads, staff members have little extra time for professional development opportunities that aid in acquiring digital literacy. Dunn County, Wisconsin's NPOs face many such challenges.

Located in rural western Wisconsin, Dunn County is served by eleven local human service agencies, most staffed by fewer than 15 people. With a small pool of employees, these agencies rarely have a person designated to address ICT issues or to train other staff. In addition to having few staff to assist the mounting number of clients, many Dunn County agencies are staffed by senior citizen volunteers who lack familiarity and comfort with ICT.

This case study examines the introduction of digital literacy initiatives by the United Way of Dunn County and ten of its partner agencies. Developed by an AmeriCorps*VISTA (AC*V) volunteer program assigned through Wisconsin Campus Compact to the University of Wisconsin-Stout, Bridging the Digital Divide in Dunn County, Wisconsin has met with successes and challenges. The AC*V volunteers observed the capacity of the NPOs to use ICT in their work and subsequently trained their staff to use those technologies more effectively. Three AC*V volunteers staffed this effort in three successive years (2010-2012). While this case study examines year one outcomes in full, the outcomes of years two and three are also briefly summarized later in the case study.

Literature ReviewMany NPO staff members are still unfamiliar with ICT, whether it be the use of websites to publish information, social media, or even the physical devices used to interact with the web, making it difficult to apply them to their area of advocacy. However, the information age requires this new set of skills to ensure success. Adeyemon (2009) argues that digital literacy learning is instrumental in fostering an understanding and appreciation of technology and building confidence to use technology. The Bridging the Digital Divide project aims to develop learning opportunities targeting agency staff who know little about the applications of online resources and new media. With these training resources, the AC*V project strives to eliminate any apprehensions or fears that affect agencies' online outreach efforts.

The catalyst for this project for Dunn County NPOs was the potential of ICT for outreach to clients and those who support their causes. Websites have long been a method of projecting NPOs' presence via the World Wide Web. Nonprofit websites often contain information regarding donations, volunteers and events, all opportunities for community involvement. Greenberg and MacAulay (2009) observed nonprofit websites to be "locked in a broadcast paradigm…using their online presence to disseminate messages broadly to a mass audience." With this one-way communication mindset, many nonprofit websites have taken the shape of an expanded "brochure" (Wagner, 1998) with little attention to aesthetics and usability.

Unlike most websites, social media allow for two-way communication, causing platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to be recognized as important tools for NPOs. According to the Nonprofit Technology Network's (2011:19) Nonprofit Social Network Benchmark Report, 87% of human service NPOs were using Facebook, primarily for marketing purposes. Twitter is the second-most popular social network in the nonprofit world with a 57% adoption rate. Social media platforms have played roles in social change from rallying thousands of Facebook users to support Egyptian democratization (Vericat, 2010) to raising $1.2 million for nonprofits worldwide via Twitter (Connect the Dots Foundation, 2011). The networking capabilities of social media have the potential to impact local issues which directly affect citizens; however, knowledge of those platforms is necessary before they can be harnessed for outreach and advocacy purposes.

Hill and White (2000:38) found that the Internet is a "B-list" activity in the workplace. Their interviews revealed that, while businesses and organizations felt that ICT is useful in remaining relevant in the "Information Age," several barriers prevented them from including Internet activities as a high priority. Public relations practitioners cited a lack of deadlines for updating material and already having too many responsibilities. With a small number of staff and increased number of clients due to economic recession, rural human service agencies often lack the necessary time and energy to create and maintain web presence.

While many businesses and organizations have created websites and social networking profiles, they have struggled to use ICT in ways that would improve their outreach efforts. Waters et al. (2009) observed that organizations believe social networking could benefit them, but failed to utilize all of the features provided by these networks. Donors and volunteers are among the primary visitors to nonprofits' websites and social media pages. Those users are certain to expect broad transparency full disclosure (Berman et al.,2007) from the organization, including through visual media, frequent updates regarding the organization's activity, and frequent interaction with their supporters. By neglecting their supporters' desire for information, organizations may risk the loss of human and monetary resources that are essential to their survival.

2. Community Profile: Dunn County, Wisconsin, USA

Dunn County is located in west-central Wisconsin, situated between the Eau Claire-Chippewa Falls and the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan areas. Its county seat is the City of Menomonie, home to the University of Wisconsin-Stout. With the exception of Menomonie, Dunn County is entirely rural, with a total population of 42,416 residents. 96.1% of the county's residents are white, and 27.5% have attained a Bachelor's degree or higher. However, 15.1% of the population lives at or below the poverty line, 1.6% greater than the national average (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009).

Internet access is an issue of concern in rural Wisconsin. While 98.9% of rural Wisconsin has access to high-speed Internet providers (National Telecommunications and Information Administration, 2011), many rural communities lack choices of providers, which can make broadband costly. While no research exists on the Dunn County residents' ICT habits, the LinkWISCONSIN Consumer Broadband Study (2010) provided insight into how Wisconsinites use high-speed Internet access and their opinions regarding Internet use. Region 3, which included Dunn County among several other counties in West-Central Wisconsin, had a 74% adoption rate of broadband Internet services. In Region 3, the 39% without broadband felt that they would be motivated to adopt broadband service if it were less costly. Overall, one-quarter of those without broadband were not motivated to get it, indicating some West-Central Wisconsinites are uncertain how broadband service is relevant to their lives in rural areas.

3. Dunn County Stakeholder Agencies

Dunn County is served by the United Way of Dunn County and 26 partner agencies. This paper focuses on the United Way plus ten human service agencies with locations in Dunn County. These 11 agencies are stakeholders in the Bridging the Digital Divide in Dunn County AC*V project. These agencies received training and took part in advising the project.

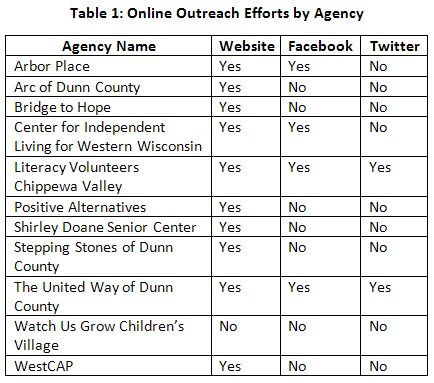

Nine of the 11 stakeholder agencies have websites. Agencies' web presence prior to the AC*V's training initiatives was largely static. Those agencies seeking a more user-friendly way of keeping the community informed adopted social media. Of the 11 stakeholder agencies, six had a Facebook page and two had a Twitter account as of August 2010. Agencies used social media sparsely, mainly to promote events. Conversations with staff suggested that client's habits have hindered agencies' adoption of web technologies. Since many of the stakeholder agencies' clients are low-income individuals who do not have Internet access at home, agencies felt that online outreach was unnecessary.

Dunn County's NPOs have a high rate of broadband adoption. 100% of stakeholder agencies have some form of Internet access. Agencies reported that they use the Internet primarily for email.

Other uses for technology among Dunn County agencies include word processing and managing spreadsheets. While agencies believe that technology is necessary in the work that they do, managing technology is not the primary strength of agency staff, and most do not have any trained IT staff. Many agencies assign one or two staff members to manage the agency's online presence or look to local telecommunications companies for assistance.

With the advent of social media, Dunn County's NPOs are beginning to realize that ICT and digital literacy skills are important tools. The Bridging the Digital Divide in Dunn County AC*V project aims to improve digital literacy skills among agency members to help them use ICT to achieve their missions.

4. AC*V

AC*V (Volunteers in Service to America) is a national volunteer program focused on eliminating poverty in the United States. Established by law in 1965 by President Johnson, the VISTA program has placed over 170,000 volunteers who have worked to empower low-income communities across the nation. VISTA members create sustainable programming to provide assistance to those in need by coordinating volunteers, gaining the support of local businesses to support community programs, and strengthening local nonprofit agencies who serve low-income populations. VISTA projects extend over three to five years in order to give sufficient time to establish programs and ensure the communities' investment into sustaining them beyond the tenure of the AC*V participation.

AC*V works with several partner organizations across the United States, including Campus Compact, a national organization dedicated to integrating community service into higher education with offices in 35 states. Wisconsin Campus Compact, host organization of the project discussed in this paper, strives to instill a sense of civic responsibility through service-learning in its 34 member institutions of higher education.

5. User Assessment Survey

An asset map was designed to determine areas of need for digital literacy training for the United Way of Dunn County and its nine partner agencies. To create the asset map, the User Assessment Survey was created. Questions within it were derived loosely from the standards outlined in the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction's Academic Standards for Information & Technology Literacy (2000), and the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education's Technology Self-Assessment Tool (2009). The survey focused on the comfort level with which agency staff could complete tasks in six areas: Microsoft Windows, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft PowerPoint, their web browser, and social networking sites Facebook and Twitter.

The survey opened with a greeting, an explanation of the survey and its purpose, and a statement that all responses would be kept confidential. The body of the User Assessment Survey rates nonprofit employees' comfort with performing 72 basic to intermediate tasks on a Windows PC including navigating Windows, Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Power Point, navigating Internet resources, and social media. Respondents rated themselves as Not Comfortable (N), Somewhat Comfortable (S), or Very Comfortable (V) in performing a particular task. For the purposes of this paper, we focus on the social networking components of the survey.

6. Data Collection and Analysis

The User Assessment Survey was created using Survey Monkey and distributed by email to the executive directors of the partner agencies on August 12, 2010. Directors were asked to forward the survey to any full-time staff at their agencies or to print out the file containing the survey for distribution. Directors were additionally contacted via telephone and email in the week of distribution. Another email was sent out two weeks later as a reminder to complete the survey. Paper copies were also delivered to agencies which had not yet returned any responses. The survey was open until September 12, 2010.

The survey was originally intended to be a census of digital literacy skills of the staff of all 26 of the United Way of Dunn County's partner agencies. However, given the focus of the AC*V project, the scope was modified to include only the 11 human services agencies with offices in Dunn County, a total staff population of 81 (N=81). Of the 75 surveys started, 74 were successfully completed, for a response rate of approximately 91%.

The data were compiled in a spreadsheet by agency to determine the areas of each agency's most critical digital literacy needs. Additionally, frequency tables were generated to analyze overall digital literacy among the 11 agencies. Analysis of frequency tables showed that most nonprofit professionals felt comfortable using the Windows operating systems as well as Microsoft Office programs. The data also showed that nearly all agency staff were comfortable with basic functions of web browsers. Overall, however, the responses indicated that social media should be the focus for the AC*V project; for any given Facebook skill at least 20% of respondents reported that they were not comfortable, while at least 70% reported being not comfortable with any given Twitter skill. The aim of the first year (2010-2011) of this project was to ensure that any nonprofit professional utilizing their organization's social media would be very comfortable with every skill.

7. Discussion

For the purposes of capacity-building, there should be one person who is confident enough with their skills to teach the task to someone who is uncertain as to how to perform it (Habel, 2009). In this way, the agencies can better influence the outcomes of the project by sharing the knowledge they have acquired with others in their organization. It was therefore decided to focus on areas where more than 50% of an agency's staff reported being very comfortable.

The survey responses and follow up showed social media to be an area where capacity-building was needed. While the fundamental Facebook tasks such as updating a status or commenting were not problem areas, other basic tasks such as using links or creating an event were found to be problematic for many respondents. Twitter proved to be even more of a challenge, with only about 13% being very comfortable with tweeting and even fewer for other tasks on the site. Based on follow-up communication with agencies, the lack of social media proficiency overall can be attributed to the fact that only one or two people manage an agency's social media. Also, only three of the participating agencies have Twitter accounts and non-users are unlikely to have those skills.

To address the problem areas reported through the User Assessment Survey, a number of programs and resources were developed by the Bridging the Digital Divide VISTA in conjunction with the Stoutreach program, which coordinates volunteer efforts in the student Involvement Center at UW-Stout. The first resource developed was the Stoutreach Technology Resource Manual. The manual, a beginner's guide, leads agency staff to explore operating systems (i.e. Microsoft Windows) and using the Internet with a focus on skill-building. This manual was meant to serve the agencies with the most need and those with senior-citizen volunteers. It includes the information to build the base of skills needed for additional digital literacy education.

Building on the base of the Stoutreach Technology Resource Manual, another resource developed by the UW-Stout AC*V was the Stoutreach Tech Wiki. The idea for this website stemmed from conversations with agency executive directors and their need for a resource that could be accessed from anywhere at any time. This website was meant to broaden users' knowledge of ICT-related terms and concepts, as well as to host skill-building exercises and guides which explain common processes that agency staff may not yet be able to execute. Furthermore, wiki sites promote participation (Knobel & Lankshear, 2009) through commenting features and editing abilities. The Stoutreach Tech Wiki also provided links to online tutorials on the various applications used by the agencies. The site was built by the AC*V volunteers. The site launched in September 2010 with content being added frequently over the following two months.

Day and Farenden (2007) observed the impact of participatory learning workshops (PLWs) on community learning and subsequently on community development. They found that PLWs were an effective means of introducing communications technologies, which in turn developed a desire by users to utilize those resources (p. 8). This supports the notion presented by Tharp (2005) that face-to-face social interaction among senior citizens can be a motivating factor in developing ICT skills. Based on this information, a presentation series called Tech Lunch began in November 2010. The AC*V volunteer served as the presenter and led discussions about how to use new media such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube to improve agency outreach. Held on a monthly basis at the office of the United Way of Dunn County, Tech Lunch provided agency staff with a comfortable environment to ask questions and present ideas and concerns about adopting new technology. At the time of writing, Tech Lunch has covered introductions to Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Google Apps, online fundraising applications, upgrading hardware and software inexpensively, and maintaining effective websites.

Adeyemon (2009:90) noted that "learning facilitators" - individuals who served to teach and mentor trainees - were essential to the success of the digital literacy training of underserved populations. Over the course of the year, the AC*V volunteer offered to give on-site, individual training with agency staff to address their concerns. Contact was generally initiated by the agencies requesting assistance with their Facebook pages or their websites. VISTA volunteers responded by addressing the issues presented by the trainee and suggesting other useful functions of the application while the trainee operated the computer. For additional support, VISTA staff members [volunteers?] were available to answer questions remotely after the training session.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

The User Assessment Survey was helpful for determining the areas in which the AC*V should develop training resources. Based on its results, social media proved to be an area of need overall. Because that need was so broad, the UW-Stout AC*V felt that the most effective means of meeting the Dunn County nonprofit community's needs was by developing a presentation series. Since its inception, the Tech Lunch series has proven effective in introducing nonprofits to new media such as social networking sites and video-sharing sites.

During the year that the resources and programs were created and distributed, the agencies' web presence has improved. Over the course of the year, three of the 11 Dunn County agencies redesigned their websites. Also, five of the seven agencies that did not have a Facebook page before the project began, created a page for their organization. This resulted in an 82% adoption rate among the Dunn County stakeholder agencies.

Community-wide success of the Tech Lunch presentations was impeded by poor attendance. The initial presentation was worked into a United Way meeting which the executive directors of all 26 of the United Way of Dunn County's partner agencies were expected to attend. However, since the initial presentation, the average Tech Lunch has brought in four attendees, two of whom are regular attendees. Since November 2010, representatives from seven of the eleven agencies have attended Tech Lunch. Increasing attendance would improve the impact of this project as it moves ahead.

The most successful means of helping agencies adopt and maintain web-based technologies in year one was through one-on-one meetings with those who have been designated to manage them. These individuals expressed desire to implement ICT, particularly social media, in their outreach, but were uncertain where to begin. Having an experienced trainer sitting by to guide the processes of managing websites and social media outlets was useful to participants. Participants were further reassured when they realized the same trainer would be available to answer questions.

While the 2010 User Assessment Survey provided the UW-Stout AC*V with an understanding of which web technologies are used by Dunn County nonprofits, it failed to address how they are being used. Knowledge of the basic functions of web browsers, email, and social media platforms does not necessarily mean that these platforms are being used for outreach purposes. In future assessment, short answer open-ended questions should be included to address the specific reasons agency staff members use ICT in their work.

The 2010 User Assessment Survey also did not assess individual level of use of technology. Not all agency staff use all of the programs listed. Having information regarding what, if any, web technologies staff members use in their day-to-day work would help the UW-Stout AC*V determine the specific training needs of each individual.

Also, the 2010 User Assessment Survey did not address the ability to edit a website, an essential tool for nonprofits' web outreach. This is a complicated issue since agencies use different means of maintaining their websites: one of many simple editors that do not require coding knowledge, delegating webmaster duties to a volunteer, or paying an outside company. Questions regarding how each agency has managed their website historically, how they intend to manage it in the future, and whether or not agency staff members need training have not been quantified in the same manner as the tasks mentioned in the User Assessment Survey. Since standardization and complexity are issues for this question, other means of understanding will need to be sought. An interview with agencies' executive directors may be the best way to obtain this information.

The Bridging the Digital Divide in Dunn County project's key success in the first year of the project was in changing the attitudes of Dunn County's nonprofit staff regarding communication technologies, although only small changes of other aspects of the project were observed throughout the year. As the project began, agency staff members exuded a sense of uncertainty regarding ICT and how to utilize it effectively. As a result, websites and social media outreach efforts often fell by the wayside. However, the timidity that had been expressed initially has been replaced by a desire to understand ICT and apply that knowledge to the betterment of their agency. One executive director remarked, "We raised $700 from [one] posting and it was the first time we had attempted to raise any funds via Facebook. That was really an eye-opener."

Maintaining the enthusiasm of Dunn County's human service agencies about increasing their digital literacy is essential to the continued success of this initiative through its second and third years and beyond.

9. Postscript: Year Two and Year Three:

The AC*V mission is to end poverty. By bringing human service agencies to a more sophisticated level of expertise in ICT, it enables agency staff to better meet the needs of the populations they serve. The goal of the Bridging the Technology Divide program is to overcome poverty through technology literacy, initially in NPO settings utilizing ICT. Three individuals worked in three successive years on this project, each leaving their own mark on the capacity of the local community.

In 2011-2012, year two of this effort, an additional 26 agency training sessions were held with 97 individuals. The most popular topics covered were the WordPress blogging program and social media. The second AC*V volunteer (2011-2012) continued with successful website and social media training implementations at seven local service agencies (Schroeder, 2012). Also:

The Community Technology Literacy Program serving local residents was launched in early 2012 through collaborations with support from community organizations. Programs included classes and Hands-on-Labs held at the local public library and senior center. Fourteen classes were offered serving 147 participants, and 19 hands-on (open) labs served 80 participants. Every participant was surveyed following the class and/or lab experience. 98% of the participants self-reported improved technology skills, including the following comments: "I always felt like run-rabbit-run and had phobias about computers. That has changed with these progressive classes" and "He helped me find another job through my applying with the computer" (Schroeder, 2012).

Additional AC*V efforts that changed the view of technology use in year two included provision of a data management solution for the holiday giving for children program. The solution immediately improved data integrity and staff time/effort. The Executive Director of the United Way indicated "It will easily save us half the time it would have taken if we utilized the spreadsheet I used for the last few years" (Schroeder, 2012). This is a project that impacts 1,600-2,000 local children annually. Streamlining management processes allowed for faster, better service that met client needs.

The AC*V volunteer also collaborated with UW Extension staff on a grant project "Reaching Families on the Go with Mobile Technology". This $22,000 grant allowed for the purchase of 12 iPads, 2 MacBook Pros and AV Equipment, and funding to support a new website for initiatives (as well as to archive past content). Equipment purchased may be borrowed by community members or agencies.

In brief, the AC*V volunteer for year two of the project mentored 30 agency staff members, trained 325 local residents, and recruited 18 community and university student volunteers who logged 196 hours (Schroeder, 2012).

An additional community support began at the bridge between years two and three. A public-facing volunteer calendar hosted through a software program held at the University became accessible for 25 local agencies that chose to participate in additional training. Each agency was afforded their own portal through which they could post volunteer opportunities, track volunteer training and hours, and obtain data for individual agency reporting structures. The VISTA in year two launched this project, and the VISTA for year three continued with the training efforts. Nine months into year three, the 25 agencies had been able to post well over 200 (one-time and ongoing) volunteer opportunities in this system. Students can connect easily and are able to include volunteer efforts in an online portfolio. The community may also access the calendar, but must contact the agency directly to sign up for volunteer opportunities (rather than sign up online).

Other efforts in year three of Bridging the Technology Divide included the renewed effort to expand the asset map and successfully garner further collaborative support for technology literacy education. Most recently, the AC*V volunteer is working with Workforce Resource on development of a standardized tutoring program and checklist for technology literacy to be used by tutors, clients and trainers. Partners in this project now included the local technical college, Chamber of Commerce, Literacy Volunteers, the School District, regional telecommunications businesses, State Workforce office, civic organizations, a retirees group, and representatives of the Marketing/ Business Education Department at the University. A local civic leadership project group offered to aid in promoting the sustainability of this project, thereby expanding the asset map. Commitments have been made by eight of these organizations to continue collaborations that will sustain the technology literacy efforts begun in 2010 by successive AC*V volunteers.

The current AC*V volunteer has also engaged citizens in a local township who expressed interest in modifying the township's web presence, expanding community access to important resources online. With his assistance, township leaders have surveyed town residents (73% response) about the web presence. They now have an updated and fully accessible website, along with a cadre of citizens who have agreed to aid in keeping information current (Schiel, 2013).

In the first three successive quarters of year three, 433 persons received training. Five faculty members and 43 students supported training efforts. Representatives of community organizations were logged in as resources 375 times. The trend toward participation by those in need of technology literacy is improving, as is the commitment on the part of the community. Dunn County has seen real, measurable change in just three years. What started in year one as NPOs using ITC has grown to meet the broader, changing needs of the local community (Schiel, 2013).

Technology literacy as an indicator of economic opportunity will be measured in the years to come through the efforts of the agency staff members who have agreed to work collaboratively in sustaining local technology literacy efforts for underserved populations. The goals of this AC*V project have been met by three successive persons who dedicated a year of their time, energy and immense talent in service to the community in collaboration with a cadre of agency and community representatives who were willing to aid in moving significant social action.