Understanding Broadband Infrastructure Development in Remote and Rural Communities - a Staged and Reflexive Approach

- Researcher of Innovation, Infrastructure and Information Technology, Western Norway Research Institute, Sogndal, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]

- Head of Research of Innovation, Infrastructure and Information Technology, Western Norway Research Institute, Sogndal, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]

- Researcher of Innovation, Infrastructure and Information Technology, Western Norway Research Institute, Sogndal, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

This article compares the broadband development in Norway with Sawhney's (1992, 2003) staged model for infrastructure development. We extend the model by taking into account actions taken by the regional actors in order to ensure infrastructure development in rural and remote areas. Further, we aim to make a contribution to research on development of information infrastructures (Hanseth 2000, Hanseth and Lyytinen 2006, Monteiro 2000, Star and Ruhleder 1996), but with a focus on the rural and remote context (Skogseid 2008). The rural and organisational context and the technological components mutually influence each other in the process of developing rural information infrastructures.

The starting point for this analysis is the staged model for infrastructure development (Sawhney 1992, 2003), a description of stages of a typical development process. We compare broadband development in rural and remote parts of Norway against this model to decipher the process and to explore how this process is a reflexive process which takes into consideration previous experience, local context and feedback and changes in technology.

While the staged infrastructure development model describes typical development steps as experienced in the US, we apply this to the Norwegian setting. Sawhney (2003) notes "each country has its own infrastructure development pattern". We see the move from the US to Europe as relevant because of the change in policy for the development of telecommunication (telecom) infrastructure from a centrally managed roll-out of technology to a new market-driven development policy. In the US the tendency is to develop infrastructure "in a decentralized, uncoordinated and bottom-up manner… not guided by a blueprint, a grand plan, or a vision of any sort" (Sawhney 2003). In this article we claim that the same patterns of infrastructure development are present in Norway.

In the past, Norwegian providers of radio, television, telegraph and telephone infrastructures took a top-down approach to develop communication systems. The providers planned and installed their infrastructure without much interaction and influence by local actors. For the telecom market, this changed in 1998 when the market was deregulated. It is no longer an agreed national policy to roll out new telecom infrastructure using a grand national plan, but rather to let the telecom providers develop infrastructure according to their prognosis for market demand.

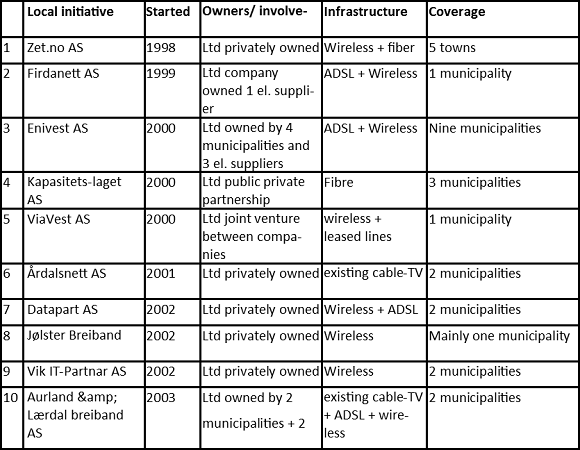

Before 1998 only Telenor, the national Norwegian telecom provider, could own telecom infrastructure that extended beyond one building. In 1998, deregulation of the Norwegian telecom market took place, and afterwards other actors were able to develop, operate and own competing infrastructure. As a result a number of local, regional and national initiatives have emerged to provide access to infrastructure in competition with the national provider or in areas where the national providers did not find any market. A study completed in 2004 identified 130 broadband providers in Norway (Norsk Telecom 2004), and in 2006 a similar study identified 150 providers (Post- & Teletilsynet 2006). In 2004, about 10 of the 130 were categorized as national providers who deliver broadband services with national coverage. About 40 were defined as "regional actors", and the remaining 80 were characterised as local providers serving local communities. The emergence of many small local providers was the response to the need to address local needs and initiatives. The municipalities participated as owners for about 50 of these initiatives (Norsk Telecom 2004). In the case region Sogn & Fjordane, one of 19 regions in Norway, a number of local and regional providers emerged and played an important role in development of local broadband infrastructure. This paper explores the further development of these local and regional providers.

In this paper, we analyse the Norwegian broadband development process to explore if the Norwegian development is in accordance with the US model using Sawhney's model for infrastructure development. While we discuss how the model is relevant and applicable in a Norwegian context, we see the need to extend and strengthen the model by taking into account local reflexive processes taking local context, feedback and learning, and global change forces. In initiating a timely infrastructure development to meet local needs, it is important to have a staged reflexive approach. We argue this will not only make the original model more complete but also relevant to broadband infrastructure development in rural and remote areas. Local entrepreneurs, local and regional authorities, and the business community should find this as a useful reference model to understand how the local development processes fits into the larger perspective. The model provides a path of development that allows local and regional initiatives to aggregate and grow.

This extended model can be a reference model for local and regional stakeholders who are facing broadband infrastructure challenges.

RELATED RESEARCH

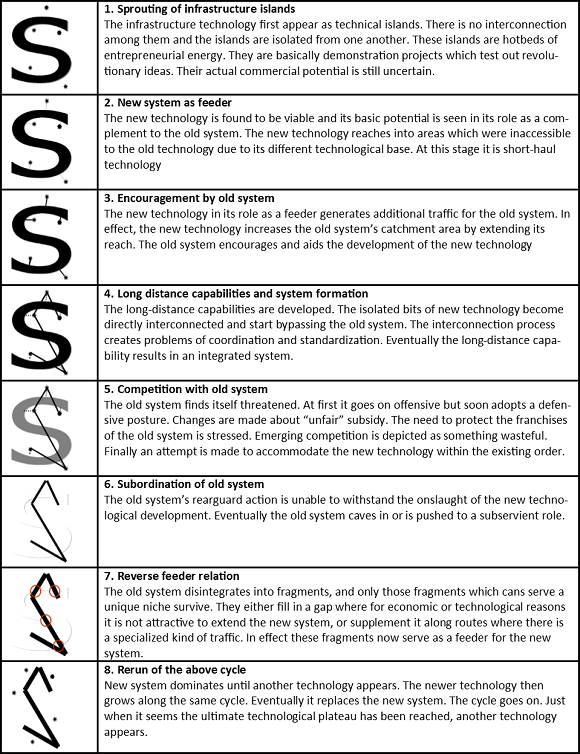

At the time of deregulation of the Norwegian telecom market in 1998 the national providers saw little market potential in the Sogn & Fjordane region in West Norway due to low population density. However, actors in the region saw a need to initiate local actions. Sawhney (1992, 2003) explores infrastructure development based on such bottom up initiatives. He defines development of new infrastructures in eight stages as illustrated in Table 1 below.

The staged model outlines how infrastructure develops based on already existing infrastructure, which equally constrains and influences the design of new components and the evolution of the new infrastructure. This staged model adds to the research previously done on information technology infrastructure development (e.g. Hanseth 2000, Hanseth and Lyytinen 2006, Star and Ruhleder 1996).

Sandvig (2012) describes five different motivations for developing local community networks:

- The network as an example of revolutionary infrastructure creation

- The network as an example of user autonomy and protest

- The network as an example of professionalization

- The network as a learning community

- The alternative: Context of no context

We see this as a complementary and relevant perspective to understand the development of local infrastructure initiatives, as we see several of these motivations can apply to the development in the Sogn & Fjordane region.

The conventions, practice or working routine of a community, can both shape and be shaped by the infrastructure (Star and Ruhleder 1996), and must be taken into consideration in the design process. Infrastructure, within this perspective, is never developed from scratch, but rather builds on something and continuously interacts with it (Hanseth 2000, 2002, Hanseth and Lyytinen 2006). When changed or improved, the new version has to fit with the existing infrastructure. This 'something' is often termed the installed base. This approach to development implies that infrastructure is something which evolves over time (Star and Ruhleder 1996). When changing or improving infrastructure, the new version must fit within the existing infrastructure. In line with this, Sawhney (2003, p. 25) states:

"…technology does not strike roots and grow on a virgin ground. Instead, it encounters a terrain marked by old technologies. The new technology's growth then is shaped not only by its own potentialities but also the opportunities and restraints created by the systems based on old technologies."

Viewing development of information infrastructures through the lens of the staged model of infrastructure development (Table 1), new infrastructure is often initially found as a feeder system to the old system (stage 2), and often with encouragement from the old system (stage 3). As it grows in scale and gains more capabilities (stage 4) it comes into competition (stage 5) with the old system, and makes the old system a subordinate infrastructure (stage 6), in the end it may reverse the system relations as the old system becomes a feeder into the new infrastructure (stage 7), this is the start of the rerun of the cycle (stage 8).

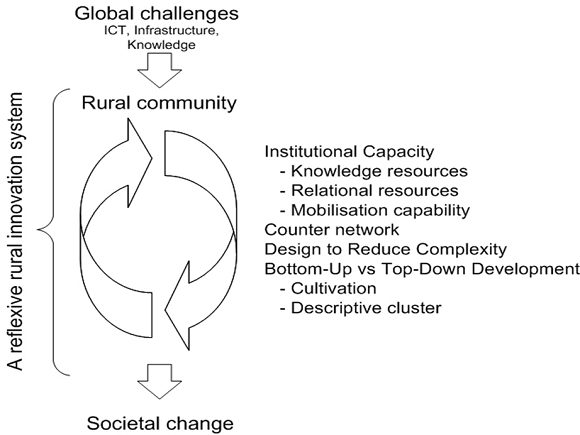

We see this development as a reflexive development. In contemporary society, local communities are highly influenced by national and global developments. In 1999 only major urban centres had access to broadband infrastructure with a capacity and a cost that allowed many companies with broadband needs to enter the marketplace without competitive disadvantages (Egell-Johnsen 1999). This allowed for a development strategy of "shaping society from below" (Beck, et al. 1994 p. 23), where local initiatives have a place in ensuring development as a counter network and also an example of user autonomy or protest (Sandvig, 2012) against the centralised demand based development. This development is a result of both external and internal change forces and result of a socio-technical development, where social relations contribute to shape technology and technology contributes to shape social relations (e.g. Monteiro, 2000). The result is a constant process of planning and modifying plans, characterised equally by both reflex and by reflection by the people involved in the process (Szerszynski, et al. 1996 p. 7). Further, external forces such as global change have forced rural and remote communities to reflect and plan how to maintain their way of life in an increasingly globalized world, and have led them to reflect and react to these developments. In parallel, the institutional capacity (Healey, et al. 1999), the involved knowledge and relational resources make sure that local experience is incorporated to influence the reflection and the modification of plans. The local mobilization is often motivated by the need to counter a development (counter network (Skogseid, 2007) and user autonomy or protest (Sandvig 2012)) with the aim ensure that the local community takes part in the development and are not left behind. The sum of this process is called reflexivity (Beck, et al. 1994, Lash 2003). This process is illustrated in the figure below identifying a number of factors influencing the introduction of information technology in a rural context (Skogseid 2007).

Reflexivity occurs in relation to contexts where the social and technical spheres meet (Lash 2003 p. 55). When the social spheres have choice in how they can respond to challenges, the response needs to be immediate to avoid falling too far behind in development. The active response is often to "put together networks, construct alliances, make deals…" (Lash 2003 p. 51) to ensure that the community takes part in development.

In the case discussion we will draw on these research contributions to understand the development in the case region.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND CONTEXT

We apply Sawhney's staged model for infrastructure development (1992, 2003) in a Norwegian rural and remote context to see if this model can be used to explore these development efforts. We use the stages defined in the model to explore an existing case on the development of broadband infrastructure in the Sogn & Fjordane region. We use an action research approach in which we were participants in the development and our conclusions are grounded in this action research (Greenwood and Levin 2007).

Case study research is "the study of the particularity and complexity of a single case, coming to understand its activity within important circumstances" (Stake 1995 p. xi). Our study is a single case where we look into a specific region. Within the region there were many instances of local initiatives but our level of analysis is at the regional level covering the full geographical area of Sogn & Fjordane region. According to Yin (1981) the strength of the case study is that it both covers a contemporary phenomenon and its context (p. 98-99). Our findings are from a single case, but we claim that these findings also can be a "force of example" (Flyvbjerg 2006) for other regions facing similar challenges.

We have been participants in the development of broadband infrastructure in the case region. Our roles in the development have been as participant, writers of application for funding, project managers and discussion partners for the County Council and the Municipalities in the region. Greenwood and Levin (2007) define action research as collaborative social research carried out by a team of action researchers and members of local organizations who are trying to improve the local situations. Together, the researcher and the actors "define the problem to be examined, cogenerate relevant knowledge about them, learn and execute social research techniques, take actions, and interpret the results of actions based on what they have learned" (Greenwood and Levin 2007 p. 3).

Stakeholders in the region have participated actively in the process through a joint effort. Since 1995 the region has had its own regional information technology task force, IT-forum Sogn & Fjordane. Until 2003 the broadband issues were handled by the broader IT-forum. In 2003 broadband development was such an important issue that they decided to establish a specialized broadband forum. Broadband forum Sogn & Fjordane was established as a sub-group under IT-forum. It has developed into the regional forum for strategy, development, monitoring of broadband status and feedback of knowledge to all the 26 municipalities and the business community.

In 2003, the broadband forum executive committee was represented by:

- One representative of 8 municipalities of the sub-region Nordfjord

- One representative of 10 municipalities of the sub-region Sunnfjord and Ytre Sogn

- One representative of 8 municipalities of the sub-region Sogn

- One representative of the Sogn & Fjordane county council

- One representing the business community

- One representative from the research and education system (=one of the authors)

In 2012, the executive committee was extended to also include:

- One representative from county governor representing emergency planning unit

- One representative from the association of municipalities

- One representative from the Confederation of employers

The basic structure is stable and the expansion reflects the importance and relevance in the region. The basic structure includes one representative from three geographical sub-groups of municipalities have proven efficient in handling the total number of 26 municipalities.

The broadband forum included the following activities:

- Information and mobilization

- Local information meetings

- National broadband conference

- Developing and updating a regional broadband strategy

- Monitoring broadband coverage and development

- Lobbying national and regional authorities for funding

- Local projects

- Proposing criteria to regional authorities for funding of local projects

- Evaluation of local project proposals

- Monitoring project status and development

- Dissemination of local experience, knowledge and results

A research team has supported the forum as a secretariat ensuring documentation and knowledge transfer. The three authors of the paper have been part of this research team from the beginning. The activities have run in annual cycles, and have proved sustainable both with regard to maintaining and improving development for broadband access. It is a 10 year experience in providing a learning community, information, monitoring, documenting and feeding the initiatives with knowledge and experience.

Research data was collected during our work as researchers, developers, project managers and evaluators of these different initiatives and our work as members of the broadband forum. The work is documented by status reports from a number of different publicly supported broadband initiatives, minutes of meetings from Broadband Forum, annual reports documenting the broadband coverage in each municipality and our collection of research memos. Local and national newspapers have written about the results of the projects. The research presented in this paper is part of an ongoing research effort (Skogseid and Strand 2003, Skogseid and Hanseth 2005, Skogseid 2007, 2008).

CASE DESCRIPTION

Basic broadband1infrastructure has been successfully completed across one of the most challenging regions of Norway, and local and regional initiatives have played a key role in this achievement. The Sogn & Fjordane region is sparsely populated and characterised by harsh natural conditions, such as glaciers, mountains and fjords which separate the towns and villages. This makes it one of the most difficult areas in Norway to develop, especially with regard to infrastructures.

The Sogn & Fjordane region has 107,000 inhabitants, and covers 18,634 square km. With only 5.7 inhabitants per square km, it is a sparsely populated region. In spite of this, all towns and most villages have broadband access, or 99 % of the population (FAD 2012). It is expensive to reach full coverage. To achieve this coverage has been an effort characterized by information sharing, learning, coordination of funding sources and joint projects to develop and establish services and stimulating demand.

THE FIRST CYCLE - THE DEVELOPMENT OF ANALOGUE TELECOM INFRASTRUCTURE

The telephone as a communication medium has a long history in the Sogn & Fjordane region. While this case is not about the implementation of the phone system, there are significant similarities between the past and the present. Local private cooperatives developed the first telephone services in Norway.

- The first telegraph installation was installed in 1858 (Norsk Telemuseum 2009a).

- The first telephone line was installed in 1889 connecting village Gudvangen to Voss (NRK Fylkesleksikon 2009), only nine years after the first telephony exchange was opened in Norway (Norsk Telemuseum 2009b, year 1880).

The Telegraph Act of 1899 regulated the market by giving the government exclusive right to operate telephone services in Norway. Over a period of 75 years the government owned Telegrafverket2 took control over more than 200 privately owned telephone companies, the last one as late as 1974 (Norsk Telemuseum 2009b, year 1974). In the same period the phone infrastructure was further developed and finally fully automated nationwide. The last manual exchange was operated until 1993 and was replaces by a mobile phone service (Norsk Telemuseum 2006). In 1988 Televerket lost its monopoly for selling phones. In 1991 they got their first competitor when both Televerket and NetCom got licence to develop the GSM mobile telephony (NetCom was operational from 1993 (Norsk Telemuseum 2006)).

This description serves as a backdrop to our case, which considers the development of digital communication infrastructure in a deregulated telecom market with basic broadband infrastructure as a result.

THE SECOND CYCLE - THE DEVELOPMENT OF BASIC DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Using Sawhney's staged model, we will now describe the development of broadband infrastructure in Norway. In 1991, Norway began to shift from analogue communication to high speed digital communication.

Stage 1. Pre 1995 Introduction of digital communication

During the 1980- and 90s the number of computers increased. More and more companies developed local area networks, e.g. islands of communication (stage 1). With this, the need for data communication across telecom networks increased. In the early 1990s the existing telecom network consisted of a mix of analogue and digital components and had low speed and capacity.

In 1992 (Norsk Telemuseum 2006) the national roll out of a new digital telecom network was initiated based on the Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN ) standard. ISDN allows the integration of speech, data and images across the lines already in place, but the switches needed to be replaced. In 1994 ISDN was offered to the business community and in 1996 it was offered to the private market. This new digital alternative was presented as a new opportunity for higher speed and high capacity digital communication. The analogue modem based communication typically offered speeds up to 56 kbps and a time consuming connection process, while the ISDN-connection offer speeds of 64 kbps or 128 kbps and a faster connecting process.

In Sogn & Fjordane a number of companies started using digital communication early, particularly companies involved in import and export. This electronic document interchange (EDI) technology was one of the first to be used (Grøtte 1993). Other data communication applications used was related to bank transactions and within health services.

From 1994 until 1996 private users and businesses still communicated using modems on analogue telephone lines. A study from 1996 shows that the ISDN penetration in the region was low (3-6%) (Wielbo, et al. 1996). At this time, Televerket was the only telecom provider who rolled out the infrastructure and delivered services to the whole country. They provided all telecom lines both for the general public and special leased lines for the larger organisations.

A number of different services were offered for data communication at different speed and capacity (analogue lines, ISDN, Fixed digital lines etc). The highest connection was enjoyed by the regional University College who was connected to Uninett, the national network which connected all universities and colleges in Norway and acted as the national testing ground for new high speed digital communication.

At this time the issue was not if regional customers would get access to new services, but when they would get access. The room of opportunity was related to priority in the line of rolling out service.

Stage 2. 1996-1998 Introduction of ISDN - New system as feeder

During this period, the adoption of ISDN technology increased. The business community and private users found it useful especially due to the faster connection process compared to analogue modems and the slightly higher speed. In this stage the new technology is found viable locally. However data communication services are still delivered by the old telecom provider and it can be seen as a feeder for the old system (stage 2). The national provider Telenor (in 1995 Televerket changed name to Telenor AS) had an obligation to provide universal services and the universal service included ISDN.

The high profile given to ISDN communication was also observed in the region. Local feedback showed that the demands for ISDN in the region are higher than Telenor was able to roll out. This gap between demand and offer triggered intervention and mobilization of regional political bodies like Sogn & Fjordane County Council, Municipalities and IT-forum. The regional actors developed a plan and stated the worry with regard slow roll out of ISDN. The organizations referred to the national policy which stated that everyone has the right to have ISDN-lines and that the regions will lag behind with regard to development if the roll out was not hastened.

The concern in this phase was that the national provider did not roll out ISDN fast enough. Local actors used their relational resources to mobilize and create a lobbying taskforce to demand a faster roll out. The regional council in Sogn & Fjordane made a resolution which demanded a faster ISDN rollout to all parts of the region. The regional taskforce, IT-forum, was given responsibility to follow up the resolution, and had several meetings with the national provider both in Oslo and in the region. In 1997 the provision of ISDN was contested. Some local businesses were denied ISDN service after having received several offers. The businesses ended up reporting the CEO of the national provider to the police (Eriksen, 2007). The national provider claimed that ISDN was not part of the universal service (Eriksen, 2007). The local taskforce got involved in the process and held several meetings with politicians and providers. By the end, the businesses had got their ISDN service. Their argument was that when the national provider had sent a letter with offer for ISDN to the businesses then they were obliged to deliver independent of cost.

Also at this time, businesses increasingly connected their computers together in local area networks (LAN), but regulations hindered them from connecting different LAN into a wide area network (WAN) on their own infrastructure. Communication between LAN's had to be routed through the national provider.

Stage 3. 1998 - 2000 Introduction of broadband wireless and fibre communication

1996 - 2000 saw the massive roll out of ISDN. In the end the ISDN coverage reached the whole region. A lot of local internet service providers and other services were made available and a number of new users, both businesses and private citizens, were connected. This generated new traffic and the back-bone networks were scaled up to meet the new and much higher communication volumes.

At the beginning of 1998, the Norwegian telecom market was deregulated. New telecom companies were now allowed to provide services and Telenor was obliged to give access to their back-bone network for the newcomers (those with more than 70% of the market share must open up their network to other providers (Post- & Teletilsynet 2004, Samferdselsdepartementet 2003)). For the end users who used the Internet regularly there was a clear advantage because broadband in most cases were offered at fixed price, higher speeds (512 - 2.048 mbps) and the computer could be connected at all times.

As a rural and remote region, Sogn & Fjordane did not benefit from the establishment of new national providers who gave priority to development of broadband services in the larger towns and cities. Broadband was not part of the universal service that Telenor was obliged to deliver. Local demand and the size of the marketplace was supposed to decide where broadband was to be rolled out. Sogn & Fjordane, a region with low population density and a difficult topography for building infrastructure was in a difficult position. The region was not commercially interesting for the larger national providers.

Around the same period (1998-2000), use of the Internet grew in popularity and generated need for better connection. At the start of 1999 the number of users on a weekly basis in Norway passed 30% of the population (Dagbladet 1999). The regional initiative to speed up ISDN coverage made the regional actors aware of the different levels of service. When some local information and communication technology (ICT) companies and some of the national newcomers saw a business opportunity in providing broadband services in rural areas, this development was supported by the regional actors and IT-forum. The local response was to organize "joint-ventures" between local companies and local public sector. New local companies were established, often linked to the local energy suppliers or a local ICT company. These new companies established local infrastructure by utilizing available un-terminated fibre from the energy supplier and installing new fibre to connect and extend the reach and wireless radio to reach the end user. The local community pooled their economic and knowledge resources of the local area to develop the infrastructure. Still, Telenor was the only provider of high capacity backbone network out of the region.

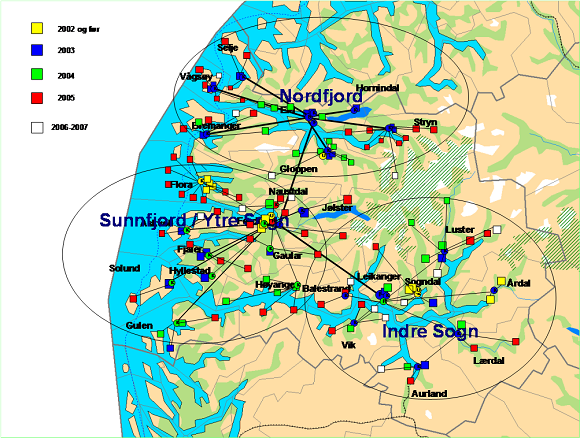

As a result a number of new local broadband companies began to emerge (see Table 2). The new local organizations had only a few persons employed who handling everything from technical issues, user support, marketing and negotiations with the provider for backbone services. The regional task force, IT-forum, supported the initiatives by providing a meeting place between the initiatives, and putting broadband on the agenda in media and political processes. The existence of these newcomers demonstrated the urgent local need and a too-small market to sustain a sufficient professional organization. As time passes and the local initiatives demonstrated their needs, Telenor and some other national actors began to provide broadband services in the most populated areas of the region, despite their initial inertia.

With deregulation, the national provider lost its monopoly. New technology, DSL, was offered for the users that needed more bandwidth than ISDN. This new technology was first offered in urban areas, and in the deregulated market digital communication was not part of the universal service that had to be provided to all. The new technology was better and cheaper than the old one but businesses who wanted to start using it were denied services at the same cost and level as in urban areas. The deregulated market also allowed local driving forces then started to build their own local infrastructure to pool resources and to connect LANs and offer broadband technology to other locals.

To illustrate the local processes, we present the example of Firdanett. Previously, a local ICT firm which had several customers who wanted to buy additional ICT services such as backup, printing and server space. Several of these customers were located in the same building, and these customers had these services made available through a LAN established in 1996. Due to regulations in the law, it was not possible to expand the LAN to other surrounding buildings on own infrastructure. With the tele-liberalization in 1998, the laws were changed and the LAN was expanded to other customers outside the building. This LAN and its services formed the basis for the development of the broadband network.

The company continued to expand the network but ran short on funds. To be able to better handle the investments a new company was established as a collaborative effort between the company, the Chamber of Commerce, the municipality, and the local energy company (Gloppen kommune 2000), and was equally owned by the partners. The company continued to develop the LAN into a full local broadband network. After a year, the new company was refinanced again and changed its name to Firdanett, which is now a fully owned by the local energy company. Firdanett offers broadband internet access and IP telephony. The local broadband infrastructure consists of a mix between fibre technology and radio transmitters / receivers. Firdanett has access to national infrastructure through a 6 Mb connection through the national provider Telenor.

As a result of this local initiative, 55 companies and 85 households received broadband internet access, despite the absence of the national provider Telenor, who at that time did not offer broadband to the households and the small businesses in this community.

Stage 4. 1999-2004 Introduction of DSL and new backbone providers

At this time the main national telecom provider Telenor pushed ISDN as much as possible to the rural and remote areas in a final period of sale before the technology reached its end-of-sale. At the same time all providers increased its DSL broadband market shares.

In this period alternative backbone transport networks were introduced, and the number of backbone service providers increased. Some of the new national telecom providers like EniTel, which utilized fibre in relation to energy infrastructure, and BaneTele, which utilized infrastructure related to the railway lines, saw an opportunity to provide backbone services to the small local companies (stage 4: long distance capabilities). In addition, Telenor was obliged to give access to their back-bone network for the newcomers (Post- & Teletilsynet 2004, Samferdselsdepartementet 2003), which opened up competition. In some towns, the local companies were now able to choose between different backbone providers, and they were able to negotiate better prices and higher capacities. In other parts of the region, Telenor was still the only provider. The infrastructure was therefore a mix of lines connected to and supporting the old infrastructure (Telenor, TeleDanmark, etc.) and the new competing infrastructure (e.g. EniTel, BaneTele).

The existence of local initiatives made it interesting for alternative backbone providers to invest in the area. The local initiatives could select between different providers and, because of the history of where the national provider had turned the locals down, the locals preferred to buy backbone net from the new providers. The towns that had alternative providers inspired others to take action and create their own local initiatives.

Broadband forum played a role in this phase by arranging information meetings all over the county to make the local communities aware of the new possibilities these new providers created. Broadband forum also helped municipalities set up plans that could be the basis for applications for national funding to speed up the implementation of broadband infrastructure in the county. Funding was provided to a number of projects, which were run with success.

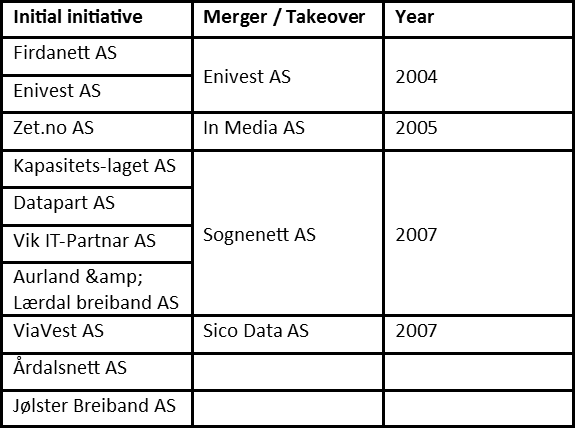

Stage 5. 2004-2007 Local initiatives reorganise into regional coverage

The local broadband providers are small organisations with, often, only one or a few employees. They were set up to meet urgent local needs. As the number of customers increased, they had to become more professional in how they carried out their operations and services and also needed to cut operational costs. Several of the local broadband providers reorganized to pool their resources, become more sustainable and be more able to meet the competition from the national providers (stage 5). In the case region several such mergers and takeovers were part of reorganisation of services (see Table 3).

From 2006 the basic broadband infrastructure was available and covered most of the Sogn & Fjordane region. The broadband providers worked together to give more specialized services, they have high capacity links out of the region and they have redundancy in the infrastructure.

As more demanding customers bought access, the local companies struggled to deliver the necessary support. They started working closer together and merged into a few professional companies. In a way the local initiatives developed from ad hoc organisations to lasting company structures, and a development from amateurs to professionals.

At the same time the most remote parts of the county still lacked broadband infrastructure. As the development continued these communities lacking coverage became the priority of the broadband forum and the struggle to obtain funding continued. More than hundred local communities got their broadband access due to the work of broadband forum.

Stage 6. 2007-2008 Subordination of old system

What started as a need to solve a local problem, where the old provider did not meet the local needs, had now developed into a completely new infrastructure and strong competitor to the old analogue telephone lines and ISDN. In 2007 active marketing of ISDN for digital communication stopped, and the market share of analogue telephone and ISDN dropped. The new infrastructure providers did not support ISDN and analogue telephone. They only provide basic broadband connections (always on connections), while services such as IP-telephony were optional add on digital services.

Stage 7. 2007-2012 Reverse feeder relation - the remaining fragments

ISDN was still offered for fixed phone lines, with the marketed advantage being its access to 2 lines. Another fragment remaining are services such as "who is calling". ISDN is still the only digital communication alternative for some remote users. Fixed-line telephony is moving to broadband based IP telephone and mobile technologies. In most areas this will trigger the close down of the old analogue and ISDN technology, and the change in technology will be complete. In 2012 Telenor announced (Post- & Teletilsynet 2012, Valmot, 2012) the closedown of these services by 2017.

Stage 8. 2012 -> Rerun of the cycle - development of next generation access

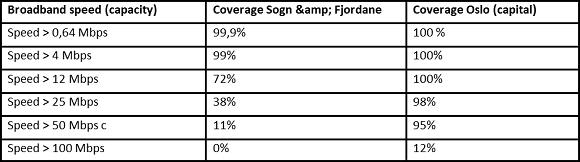

Despite the fact that 99% of the inhabitants in Sogn & Fjordane have access to basic broadband infrastructure (4 Mbps) (FAD 2012) the difference between urban and rural areas are again growing. Now the focus has shifted from basic broadband to next generation access (more than 30 Mbps (EU-commission 2010)).

The need for next generation access has been triggered by the fast growing offer of video and streaming services. These are both integrated into the traditional news services and also offered by new service providers. Internet use in Norway shows a growth of about 40 % every year (FAD 2012). One example illustrates the new momentum. When the video streaming service Netflix was launched in Norway in February 2013, the Internet usage grew 60% (FAD 2012). The table below shows coverage for different speeds.

According to Post- & Teletilsynet (2009), the drop in coverage in Sogn & Fjordane from 640 kbit/sec to the next level 4 Mbit/sec is partly due to the use of radio to access the infrastructure and partly due to the line length and the ability to deliver high capacity over long distances (more than 5.5 km copper line from the switch). The drop in coverage from 4 to 8 Mbit/sec and from 8 to 12Mbit/sec is mainly due to the line length and the ability to deliver high capacity over long distances, while speeds of more than 25Mbit/sec is only available to those having either coaxial or fibre cable.

The inhabitants of Sogn & Fjordane have now realized that they are again lagging behind. The basic broadband services rolled out to almost everyone during 1999 - 2010 is no longer enough for keeping up with the new needs for access to video and streaming service, combined with the general growth in Internet usage. Again, local community groups are formed to document the needs, the local interest and to lobby for a faster roll out of next generation broadband access. The broadband forum and its links to local municipalities are still in place. In the first run of the cycle the business clusters and local public sector organization were the most active. In the second run new ultra-local groups representing villages or neighbourhoods consisting of private households have joined the business clusters and local public sector organisation in the effort. We see indication of a new cycle of technology development starting, where local community groups and business pool resources and work together to roll out fibre lines to all households and businesses in an area. At the same time several technologies compete, such as how fibre is challenged by new high speed mobile networks and by improved satellite based broadband communication. At the moment we cannot foresee which technology is winning but the local actors are again mobilizing for action.

DISCUSSION

In the discussion below we discuss the case to develop a deeper understanding of what is happening with broadband development locally and regionally. The development is a socio-technical development. The technical development is dependent on social processes and the social processes are fed by improvements in technology. We discuss whether Sawhney's staged model is relevant in describing the Norwegian technical developments and the growth of new infrastructure. Further, we explain the local and regional processes which triggered the shift from one stage to the next and if this will complement and extend the staged model with a deeper understanding of the socio-technical development process.

This discussion is organized into three parts:

- Rural broadband access as a staged infrastructure development

- Rural broadband development as a reflexive process

- Rural broadband development as a socio-technical development

Rural broadband access as a staged infrastructure development

Sawhney's staged model for infrastructure development describes infrastructure development when it is "… not guided by a blueprint, a grand plan, or a vision of any sort" (Sawhney 2003, p. 26). This is the reality of broadband infrastructure development in Norway. The government decided broadband development should be driven by market needs and provider prognosis for the number of customers available. This left many small local communities trapped in inertia between the market and a wait-and-see public sector. Then, after some years, missed installations in areas with insufficient market potential could be considered for special public funding. In this case description we have used Sawhney's model to describe the different stages in the development of the new broadband infrastructure technology in our region. We find this model appropriate as a description and useful to understand the different stages that such a development has gone through. Sawhney's model describes stages that are also meaningful in a Norwegian context. However, in using this model we lack a description of the social processes that involve local actors, their actions and how that influence the process.

Rural broadband development as a reflexive process

The challenge in the case region was to ensure that new broadband infrastructure was built. Earlier we noted that "[r]eflexivity occurs related to contexts where the social and technical spheres meet" (Lash 2003 p. 55). When the local communities - social spheres - have a choice of responding to challenges, the response needs to be immediate to avoid falling too far behind in development. The active response is often to "put together networks, construct alliances, make deals" (Lash 2003 p. 51) to ensure that the community takes part in development.

In the case region, what started as a need to increase the speed of the ISDN rollout can be traced through a number of stages as a reflexive development. The actors have, based on global changes, made plans to assure they were not falling behind with regard to digital development and access to infrastructure. A regional task force IT-forum took up the responsibility to follow up plans and actions. Later they established a broadband forum a more specialised task force to address the specific infrastructure needs. Local actors built their own islands of new infrastructure, and a series of regional plans and projects were developed. Knowledge resources and relational resources were mobilized to cope with the global challenge. Counter networks were formed without any grand plan and, using Sandvig's (2012) categorization, there are examples of networks as learning communities (with the effort of IT-forum and broadband forum), as user autonomy and protest (the case of Firdanett and the other local initiatives), and examples of professionalization when small initiatives merged into stronger networks. The local action plans and regional task force were examples of learning communities. These processes and learning communities lead to societal change through a reflexive development (Skogseid, 2007) process.

Rural broadband development as a socio-technical development - Is there a basis for a new combined model?

The broadband development case in Sogn & Fjordane is in our view an example of a socio-technical development. The staged model offers an understanding of the dynamics of the technical infrastructure development, and the model for reflexive rural innovation system offers an understanding of the local and regional social processes needed.

The staged model represents a relevant and useful framework for understanding this infrastructure development. As we see it, the staged changes are triggered by:

- Technology changes and a large part of the users community wants the new technology which is superior in functionality and quality

- Users do not accept the long wait time for generic technologies, just to prove to national policy developers the need for public intervention

- Local communities look for sustainable solutions and secure the infrastructure after an initial phase

These dynamics trigger the formation of local initiatives, even in small communities, that may provide the basis for aggregation and development into new bigger self-sustaining systems. Looking at this process in Sogn & Fjordane combining the stages and reflexive process the case history can be summarized as follows.

The telecom market was deregulated in 1998. This development gave the regional actors an opportunity to initiate local action. Prior to this there were no room for local reflexive processes. At this time the demand for more broadband communication increased. Soon after the deregulation of the telecom market, actors in the Sogn & Fjordane region realized that they would be among the last to get broadband access and chose to initiate local collaborations to improve their own situation. To bridge the broadband divide, individuals, businesses and the public sector joined forces and took initiative to developing and operating local broadband infrastructure (starting stage 3). Several of the initiatives listed in Table 2 can be traced back to projects initiated in 1999. The development process has been one of reflection. How can we get access, what are the available technologies and knowledges and how can we pool resources? The process has also been influenced reflexively by new global events. New and better technology allowed for other technical solutions. Later on the national providers discovered, triggered by local initiatives, that there was some market potential after all and started to extend their services also in rural and remote areas (stating stage 4). The additional effect of global change processes, like the increasing importance of ICT in all parts of society, the reflexivity which through global and local feedback loops creates a continuous development process. Another effect we see is one of friendly takeovers and mergers between these local broadband companies (starting stage 5), among other to create a more sustainable operation of the network and for those taking over to expand their service area as shown in Table 3. Stage 6 and 7 does not show much local reflexivity these are stages where technology develops and changes based on momentum already gained in earlier stages. However, in stage 8 we see a new need for local reflexivity based on new needs and capacity not delivered.

CONCLUSION

Our conclusion is that Sawhney's model is relevant and applicable in a Norwegian context. However we see the need to extend and strengthen the model to include elements of local reflexive processes taking in local context, local feedback and learning and global change forces into account. By initiating a timely development to meet local needs, it is important to have a staged reflexive approach. This will make the model more complete and directly relevant to broadband infrastructure development in rural and remote areas. Local entrepreneurs, local and regional authorities and the business community should find this as a useful reference model in understanding the local development processes in a larger perspective. The model provides a path of development that allows local and regional initiatives to aggregate and grow.

After a number of years' experience with a policy based on market driven infrastructure development we can observe that the major Norwegian cities quickly got broadband access. However the rural and remote regions saw little interest among providers and no provision of broadband access. Without a close collaboration within local communities and between regional actors and local initiatives it would not have been possible to provide the basic broadband to the small villages in rural Norway, within the same time frame as is documented in this case.

By collaborating, the region's stakeholders have ensured progress in new infrastructure implementation and consolidation has progressed from one stage to the next in accordance with Sawhney's model. Our suggestion is that in order to ensure implementation of broadband infrastructure in rural and remote regions, organizational processes between the region's actors have to be developed and it all should be aggregated into an understanding. This understanding must take into account the reflexive nature of the development, local context, local feedback and global change forces. Communities needed to initiate locals actions to prevent the local community and the region from lagging behind in the critical period when national authorities needs for find out that a market driven approach is not feasible.

The key elements of the combined model is that the staged model shows a model of what is happening and the reflexive model shows how to organise it make it happen. The reflexive model is in particular relevant where local communities have a room of opportunity to influence infrastructure development, in our case history as part of stage 3-5 and in stage 8 initiating a rerun of the cycle. This combined model should be of relevance of regional broadband development issues in many rural and remote areas.

NOTES:

(1) In accordance with Norwegian (FAD 2013) government we define basic broadband as 512 Kbps -4Mbps

(2) The government owned company changed names a number of times: Telegrafverket, Den Norske Statstelegraf, Rikstelegrafen and Det Norske Telegrafvæsen. In 1933 the company was named Telegrafverket. Then in 1969 it was changed to Televerket and in January 1995 the names changed again to Telenor AS a publicly owned limited company. In 2000 Telenor AS was privatised, the government holds 53.97% of the shares (Norsk_Telemuseum, "Telehistoriske glimt. Telekommunikasjon før og nå," 2006.)