Local e-Government in Sweden - Municipal Contact Centre Implementation with Focus on Public Administrators and Citizens

1. Department of Economics & IT & PhD Cand. The Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

1. INTRODUCTION

The e-Government phenomenon is growing rapidly at the local, national and international levels (see e.g. Rose & Grant, 2010; Rabiaiah & Vandijck, 2011; Worrall, 2011), and is supported by policy organisations such as the EU, UN and OECD (Lahlou, 2005; OECD, 2009; European Commission, 2010). E-Government is connected to the "post-industrial" digital economy (Fang, 2002; Westlund, 2006; Stough, 2006) as information and communication technology (ICT). E-Government has rapidly diffused as an important managerial public reform over the past 15 years (Lee et al., 2011; Rose and Grant, 2010). The implementation of e-Government is often associated with increased public e-service availability for citizens, but it also entails a fundamental organizational change in public organizations (Grönlund, 2001; Beynon-Davies & Williams, 2003; Worrall, 2011) which is hard to manage, difficult to implement and often fails because private sector ideas cannot be transplanted into the public sector (Heeks, 2006). E-Government research has increasingly attracted attention as a part of many governmental agendas (Heeks & Bailur, 2007), and there is relatively little systematic research undertaken on the local level (Deakins et al., 2010). However, there is research showing that local e-Government, expressed as on-line services, has been adopted but not yet achieved many of the expected outcomes, and organizational and socioeconomic barriers to the transformation remain (Moon, 2002; Beynon-Davies, 2004; Torres et al. 2005; Norris & Reddick, 2012). Torres et al. (2005) argue that e-Government initiatives in most local governments are still predominantly non-interactive and non-deliberative. Most governments have a web site, although in most cases it is little more than a governmental billboard. They tend to reflect present service delivery patterns, not transform them. According to a European Union project running between 2007-2013, there is a trend in Europe of municipalities being transformed into more customer-focused organizations (Smart Cities, 2011).

In Sweden, a "Special Commission on e-Government" was established in 2009 to promote development and use of e-Government in the public sector. The main aim in the Action Plan for e-Administration developed by the Special Commission on e-Government is to "have simple, open, accessible, effective and secure e-Government" (Regeringskansliet, 2008). One example of such a change is the implementation of a municipal Contact Centre (CC)i . Andersson Bäck (2008:3) defines a contact centre as "a 'new' type of organizational form, where the organization of actions and the use of technological tools are underpinned by the logics of cost-effectiveness and customer-focus". The implementation of contact centres in Swedish municipalities is inspired by the concept of a call centre although it is transformed when adapted to Swedish culture (see further Czarniawska & Sevón, 1996). CCs are not only for local eGovernment front-line service delivery, but they also entail new organizational settings, developing practices and management in municipal public administration relating to New Public Management (NPM) (Fountain, 2001; Jansson, 2011). These processes are a front-line practice and but have to be further addressed by research to interpret practices (Lindblad-Gidlund et al., 2010; Meijer & Bannister, 2011). Swedish research shows that there is a lack of empirical studies on the implementation of contact centres in municipalities within the research field of e-Government, although some minor case studies on different perspectives have been done (e.g. Bernhard, 2009, 2010; Flensburg et al., 2009; Bernhard & Grundén, 2010; Grundén, 2010). More and more CCs are being implemented in Swedish municipalities and the possibilities to learn from such experiences will increase. However, according to a global study of e-Government (Accenture, 2007), it seems important not simply to try to imitate examples from other organizations. Instead, such examples should serve as inspiration, with awareness of the importance of local context when CCs are implemented, as CCs do not simply appear. The CCs have to be locally formed and anchored in policy making before being implemented. When policies are translated into local contexts and promote new practices, they become settled in the institutional milieu. The institutional approach emphasizes the contextual aspects of translations. In the Swedish case the constitutional local autonomy defines the lower levels of government, which will be further discussed in this paper.

This paper aims to analyze the implementation of Swedish municipal contact centres (CC) with focus on internal organization as well as on citizens, based on the following research questions:

- How has the implementation of the CC affected the work of the public administrators within the front office (CC) and those in the back office in terms of their role as suppliers of public service?

- How has the implementation of the CC affected

citizens regarding:

a) access to public municipal service?

b) "customer" approaches?

After this introduction, the article proceeds in four steps. In the next section, definitions and dimensions of e-Government as well as the role of municipal local autonomy are discussed. I will also present the idea and concept of a municipal contact centre by relating it to the theory of New Public Management in the digital era. In section three the method and four cases are presented, followed by findings in section four. These are then analysed and conclusions are discussed in section five. This section ends with implications for further research.

2. E-GOVERNMENT AND CONTACT CENTRES

E-Government is an emerging field that still lacks a single definition and a universally accepted definition (Yildiz, 2007). The national government of Sweden defines e-Government as "organizational development in public administration, which takes advantage of ICT in combination with organizational changes and new competencies" (Regeringskansliet, 2008:4). E-Government in general can be defined as "all use of information technology in the public sector" (Heeks, 2006:1). Heeks' definition is used here to encompass all use of digital information technology in the public sector, which means that it consists of technology, information and human beings who give the system purpose and meaning, and the work processes that are undertaken. Moreover, an important aim for e-Government is to bridge the gap between government and citizens, including a strong emphasis on internal administrative efficiency in the development of e-Government (Homburg, 2008). In this perspective Grant and Chau (2006:80) identify three core activities of e-Government:

"(1) to develop and deliver high quality, seamless, and integrated public services; (2) to enable effective constituent relationship management; and (3) to support the economic and social development goals of citizens, businesses, and civil society at local, state, national, and international levels".

E-Government is, in this context, further referred to as the redesign of information relationships between the administration and citizens, in order to create some sort of added value. Based on this discussion three core types of relationship and dimensions in e-Government among different actors can be identified for both analytical and practical purposes in order to further understand the distinction and relationship between them. These are e-democracy (relationships between the electorate and the elected, i.e., the political interplay of citizens and elected politicians), e-services (in the relationship between the public administration and the citizens), and finally e-administration for the internal usage of information technology tools within governmental organizations to provide reports and support for decision making (Wihlborg, 2005:7, Bernhard & Wihlborg, forthcoming 2013). In practice it is hard to make a clear division between these dimensions (Jansson, 2011). In this study the e-Government initiatives are expressed by the establishment of municipal contact centres which encompass the use of both Internet-based applications (e-services) and digital information technology (including telephones), as well as information and human beings (citizens and public administrators). The analyses are, however, based on the views of public administrators and citizens (e-services and e-administrations), as in many definitions e-democracy is excluded from e-Government (Jansson, 2011).

The contact centres aim for increased access for citizens to municipal service through multi-delivery channels. Thus a critical related issue is the concept of the "digital divide" which refers not only to the socioeconomic gap between those who have access to computers and the Internet and those who do not, but also to those who have access to quality, useful digital content such as ICT literacy and technical skills and those who do not (see e.g. Findahl, 2009, 2011). Another issue is that the Internet favours individuals with literacy skills, who often also have greater access to financial resources and education (Schwester, 2011). The development of e-Government may have essential implications for disadvantaged groups in Sweden too. Use of the Internet and computers is high in Sweden, which is ranked as one of the top countries according to international evaluation studies (Accenture 2007; United Nations, 2012). Although more than 84% of Sweden's inhabitants use the Internet (not necessarily on a daily basis), this means that there is still a digital divide (Findahl, 2011).

2.1 New Public Management in the digital era

The origins of e-Government can be seen as one type of realization of New Public Management (NPM)-type reforms in public administration (Andrews, 2008; Homburg, 2008; Jansson, 2011). E-Government has however also been regarded as a new reform in itself, not associated with NPM (Dunleavy et al., 2005). NPM-related ideas and practices have influenced the public sector in Sweden for over twenty years (Girtli Nygren & Wiklund, 2010). NPM is frequently described "as an umbrella term of management ideas from the business sector implemented in a public sector context" (Persson & Goldkuhl, 2010) or as an organizational theory (Peters & Pierre, 1998). NPM is both a practice and a theoretical conceptualisation rooted in different research fields with diverse directions (Barzelay, 2001). The key features of NPM in practice are "customer orientation, improved responsibility to address client needs, focus on cost-efficiency and productivity and introducing market mechanisms" (Persson & Goldkuhl, 2010). There is emphasis on contract-like relationships and attention given to management strategies, performance indicators, and the service produced. The use of IT is essential for this organizational transformation where IT mediates the communication between different units in different geographical locations. The theories of NPM have inspired some changes of organization and administration when e-Government is implemented and the use of lean and highly decentralized structures in public service is stressed, resulting in formerly unitary bureaucracies breaking down (Homburg, 2008). Critics of NPM argue that there are key differences between public and private sectors both in terms of overall purpose and structure of processes (e.g. Heeks, 1999).

The extensive treatment of the citizen as customer in e-Government research may be seen as inherited from NPM. One of the main elements of NPM is that the public sector develops market-like patterns of behaviour. This includes a customer orientation where citizens often will be viewed as "customers" in a market rather than as citizens with rights and duties (e.g. Collins & Butler, 2002; Michel, 2005; Montin, 2008; Wallström et al., 2009) or as clients and users (Lips, 2007; SOU 2008:97). The focus is also more on efficient public services and making public administration more citizen-oriented, efficient, transparent and responsive to the needs of the public (Hood, 1991; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Wihlborg, 2005; Bock Seegard, 2009; Rövik, 2008; Persson & Goldkuhl, 2010; Hall, 2011; Worrall, 2011). When considering the citizen from a strict service perspective, it can be argued that using the concept of customer is useful (Lindblad-Gidlund et al., 2010). However, there are also critics of viewing citizens as customers (e.g. Olsen, 2006; Cordella, 2007). Minzberg (1996) argues that customers buy products and clients buy services, but citizens have rights and the priority for them is more than a customer or client in the government sector. This is one reason to discuss the issue of the "customer" approach and the fact that most e-applications have developed as marketing tools in e-commerce, e-marketing, etc.

2.2 The Swedish settings

The Swedish multi-level government system is based on three levels: the national, regional and local levels. Public service delivery (the tasks of the public sector) is distributed among all three levels but citizen-oriented services are mainly supplied by municipalities. The 290 Swedish municipalities have a constitutional autonomy. The municipal services concern almost all service for the citizens in their everyday lives and in comparison with other public organizations, for example state authorities, municipalities are very multifaceted and handle a broad and complex set of issues such as primary and lower secondary schools, daycare institutions, elderly care, planning permits, environmental permits, matters regarding social services and schools, healthcare, and welfare, etc. (Gustafsson, 1999; SOU, 2008). There is no statutory obligation for municipalities to set up offices for citizens although it is required by law that municipalities should provide individual service, e.g. to meet visitors and respond to telephone calls from citizens (SFS, 1986). The internal context of each municipality can be very different due to different geographic locations, population, social structures and economic conditions and the development towards e-Government varies among Swedish municipalities, since the number of inhabitants and the economy varies (SALAR, 2009).

The e-Government development is given top priority in the larger municipalities and the priority level decreases with the size of the municipality (SALAR, 2011). Financing, the municipality's ability to perform business development and the existing IT-system environments are the main obstacles for municipalities in developing e-Government. Smaller municipalities also emphasize the lack of competence of the administrators as a major obstacle to advanced e-Government (ibid.). Regional and municipal administration in Sweden represents approximately 70% of public administration, where the regions mainly provide health care and the supply of urban traffic systems.

To date ninety-eight municipalities are members of Sambruk, a non-profit association financed by its member municipalities (Sambruk, 2013). The vast majority of the municipalities in Sweden are too small to make big investments in the development of new e-services or re-engineering of internal business processes. One of the aims of Sambruk is to create a strong negotiating position with IT vendors and government bodies when creating solutions based on the use of ICT.

2.3 Municipal contact centres

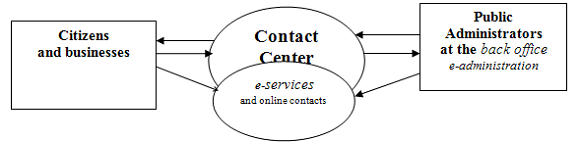

The main function of Swedish municipal CCs is to supply services to citizens more efficiently by primarily using the telephone and ICT (e.g. e-services) to handle citizen contacts (see Figure 1). When CCs are implemented in municipalities, the work of the handling officers at the administrations is supposed to become more efficient, as they will not be disturbed by phone calls involving "simple questions" from the citizens. The different organizational units (back office) are also supposed to cooperate in resolving citizens' matters, in order to simplify the citizens' contact with the municipality. The CCs aim to contribute to increased citizen access to municipal services through multi-channel service like ICT in the form of telephone, Internet, municipal websites and Web-based applications (e-services), and generally they are also open for personal visits. The municipal website is a main electronic resource for information to citizens and organizations within the municipality and the municipal e-services are published on the website.

The CCs function as the single entrance to local government, as front offices with extended opening hours (open weekdays) and staff with broad competencies to answer, supervise, and re-direct citizens to the right section of the public administration and/or on the Internet. They also have the competence to reach into back-office functions to resolve standard errands (Bernhard, 2010; Bernhard & Grundén, 2010). All issues are registered in a new information system for internal handling of matters (e-administration). Employees at the CC also initiate issues, when needed, which are transferred to public administrators at the back office using the IT tool for handling of matters.

Figure 1 shows a conceptual model of the contact centre from the perspectives of citizens and the public administrators at the CC and at the back office. Usually the e-services and on-line contacts like e-mails are handled, communicated and supported by the employees at the CC (front office), but some e-services may also be directly connected to the public administrators at the back office.

When analyzing the cases it will be in relation to the view of e-Government (CCs) as a redesign of information relationships between the administration and citizens (e-administration and e-services), in order to create some sort of added value in the perspective of some of the NPM key features.

3. METHODS AND THE FOUR CASES

A criterion for being chosen was that the municipality should be a forerunner in the development of e-Government and the implementing of a CC. The four municipalities including in this study, were all forerunners in the development of e-Government and the implementing of CCs and members of Sambrukii .

The method used is case study. Case study methodologies are preferred when you want to study an actual phenomenon in its real context, used as a research method in the social science disciplines like public administration, political science, business and marketing and evaluation (Yin, 2009). Case studies are built on interviews with people who have experiences in the actual case and on direct observation of the phenomenon. The methodology of case studies' particular strength is that it makes you allow handling many different kinds of empirical data like documents, artefacts, interviews and observations. It is classified as a meta-methodology as when studying a phenomenon in its context, different methods or techniques are required in order to get various types of data (Yin, 2009). In comparison to quantitative studies, qualitative methods are an alternative way of looking at knowledge, meaning, reality and truth in social sciences. Focus is on understanding important relationships (Kvale, 1996). Examples of what cases can be is a single organization or a single location (Bryman & Bell, 2011).

Interviews have been the main method, since CCs are a rather new phenomenon, and a variety of voices were included. In addition, documents such as policy documents, pilot report studies, revision reports and results of municipal customer surveys, have been studied. These analyses served as the intention to give me an overall understanding before doing the interviews. The documents have been used both as a background study of the e-Government practice and to get an overview of the background of the implementation of the e-Government process. Some of the documents like results of customer surveys were made by private organisations. When critically examining these documents I had in mind who had written them and for what purpose.

As this study focuses on the perspectives of both public administrators and citizens, the initial interviews took place with different personnel categories and policy makers before approaching the citizens. The interviewed personnel categories in the cases were employees from contact centres ("front offices") and from what is called "the back office" of the municipal local administration as well as from the top management of the municipalities. To cover the changing working conditions, representatives from the unions were also interviewed. The interviews were planned in accordance with Kvale (1996:88) who highlights seven steps of an interview study - thematizing, designing, interviewing, transcribing, analysing, verifying and reporting - as these are important to bring up for achieving scientific quality. Altogether the data consists of 40 semi-structured recorded interviews within the municipalities: Skellefteå - Case A (10), Botkyrka - Case B (7), Stockholm - Case C (7) and Jönköping - Case D (16), as well as of a pilot study with 21 citizens. These interviews were made in two steps: those in case A-C were recorded and made during the spring of 2009, while those in case D were made in the spring of 2010 as this contact centre was implemented in late 2009. It was important not only to include different personnel categories but the number of respondents in qualitative studies must be large enough to assure that most if not all of the perceptions that might be important are uncovered. However, if the sample is too large, the data becomes repetitive (Mason, 2010). According to Glaser and Strauss (1967), the sample size in the majority of qualitative studies should generally follow the concept of saturation but many researchers do not suggest what constitutes a sufficient sample size (Mason, 2010). According to Ritchie et al. (2003) qualitative samples often are below 50 while Green and Thorogood (2009) state that the experience of most qualitative researchers is that very little "new" in interviews comes out after interviewing 20 people or so. Each interview with personnel from the municipalities took about an hour and was tape-recorded and transcribed. Qualitative content analysis (Kvale, 1996) was used for the analysis of the interviews.

The pilot study with the citizens was an explorative study to investigate the citizens' attitudes to the newly established contact centre in case D. These interviews were held about four weeks after the CC was implemented in late 2009. When citizens who had been in contact with the public administrators at the CC ended their phone calls, they were asked if another person (a researcher) could call them back and conduct an interview regarding how well they were informed about this implementation, their opinions of the service delivered by the new municipal contact centre, if they had access or used Internet and public e-services and about how this implementation has affected their access to local municipal service in general. Of the citizens interviewed, 14 were female and 7 male. They differed in age; 6 respondents were elderly, i.e., over age 65 (2 female and 4 male); one citizen (1 male) was younger than 24 and the other 14 (13 female and 1 male) were between 25 and 65 years of age. The study with citizens was based on semi-structured telephone interviews, primarily using questions with predefined alternatives, to which some open-ended questions were added.

BenchmarkingThere are many definitions of benchmarking (Fong et al. 1998). It originates from the industry and may be defined as to when a business compares their own activities and organization with another business that has a recognized good reputation (Esaiasson et al, 2007). They argue that it may be difficult to make such comparisons within the public context. Camp (1989) refers benchmarking as finding and implementing the best practice. ReVelle (2004) discusses competitive benchmarking and defines the term as comparing how well or poorly an organization is doing with respect to the leading competition, especially with respect to critically important attributes, functions, or values associated with the organization's services or products. As a municipal contact centre is a new e-Government initiative in the Swedish local context it is difficult to do benchmarking and find a "best practice" to compare with, although the method can help identify areas or processes for improvements within these four cases. I will make comparisons and discuss them in the next section.

3.1 The Cases

Case A - Skellefteå - is by Swedish standards a medium-sized municipality (population 72,000). The municipality covers a large geographical area compared to other municipalities in Sweden and can be said to be the centre of a region (for a broader description see Bernhard, 2009). There are rural areas and one larger central city where almost half the inhabitants live (www.skelleftea.se). The municipality is organized in eight different administrative sections with responsibility for different areas. In April 2007, the first phase of a contact centre was established covering some of the administration and in February 2009 a contact centre for all administration was set up within the central city of the municipality. Here, unlike the other cases, they name the CC as a "Customer Service".

Botkyrka, Case B, is situated in the Stockholm region and this municipality too, by Swedish standards, is a medium-sized municipality (population 80,000). It is one of the most international municipalities in Sweden since almost a third of the inhabitants have roots in more than 100 countries around the world (www.botkyrka.se). They combine a contact centre, which was established in 2007, with One-Stop Government Offices for personal visits, and strive to implement more e-services. In the 1980s Botkyrka established One-Stop Government Offices in order to facilitate communication with their citizens. These are situated in the areas where most of the immigrants live.

Case C, Stockholm, is the capital of Sweden, with a larger organization than the three other municipalities in this study (population 868,000). This municipality has a high degree of decentralized responsibilities, and the official organization includes 14 district administrations in charge of most municipal services (www.stockholm.se). These district committees are responsible for many of the municipal services within their geographical area. The implementation of the contact centres started as a pilot project in two municipal districts in 2005 and then spread to the whole municipality in 2009. A big difference compared to A, B, and D is that due to the larger population, they established one contact centre giving public service only to elderly inhabitants, providing one telephone number solely for questions and services for eldercare issues. There is a different telephone number for the contact centre that concerns other issues. They have an e-strategy that aims to implement more e-services and they have a few One-Stop Government Offices in areas where many immigrants live.

Case D, Jönköping municipality, ranks among Sweden's ten largest municipalities (population 127,000) (www.jonkoping.se). It is organized in nine operative administrations. Most of these organizational units are led by boards or committees of political representatives. The departments and administrations carry out a wide range of operations such as child and youth care, education, social issues, culture and recreation, building and environment. The management of the municipality decided to implement a contact centre and work towards more e-services in 2009. The contact centre opened in November 2009. The directives were formulated in a local policy which stated for example that the use of IT should contribute to service production improvements. At this first stage the contact centre has only moved one work process to the CC, but they plan to transfer more in the next stage. The aim of the municipal guides at the CC is to answer simple questions and direct citizens to where they can find solutions to their issues. At the time the interviews were made it was not possible for citizens to visit the contact centre, but opening for personal visits was planned for early 2011.

4. FINDINGS

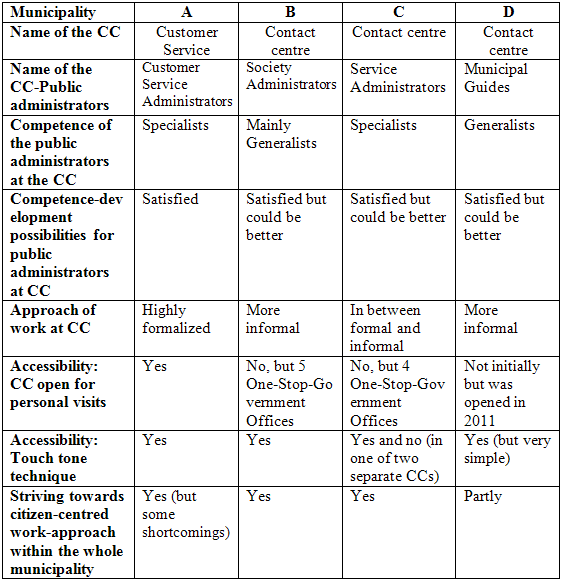

In this section, findings from the cases in relation to the research questions are discussed and compared. The main related characteristics of the cases are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, there are differences as well as similarities which imply that a municipal CC may be a slightly different concept, although they are all conceptually organized like Figure 1 (above).

4.1 The public administrators' perspective

The main focus will be on aspects of competencies and work approaches with respect to the public administrators at the CCs, in terms of their role as suppliers of public service although e-administration aspects will also be discussed. With respect to the public administrators at the back-office, the focus will be on reorganization, their work situation and anchoring aspects, in terms of their role as suppliers of public service. The reason for this is that these are the main impressions that have appeared in the cases in terms of their role as supplier of service.

Competence perspectives and work approaches of the public administrators at the CCThe competence of the public administrators at the CC differs as they are specialists in cases A and C and generalists in cases B and D. However, the difference is most obvious in case D, where their work approach is more of a guiding approach. Consequently they are called "municipal guides". Unlike in the other three cases, only one work process has been transferred from the back office to the CC. This is also seen in differences in how the work is organized. In case D and in one of the two CCs in case C, the work is not organized in different response groups. A response group refers here to a system where incoming telephone calls are connected via voicemail to a group of specialist employees, depending on the field of activity they are concerned with. In case B the telephone calls are organized in a few different response groups. In case C all employees are specialists within a certain area, which means that there is no need for response groups as this CC is solely concerned with supplying service to elderly inhabitants. In case B most of the public administrators have a broad range of knowledge, but some of them are also specialists within a certain area. Their competence profile could therefore be characterized as generalists rather than specialists.

In all cases, except case A, there seemed to be a certain lack of time for training to increase competence levels. There was a need in all cases for the public administrators at the CC to have continually updated knowledge: for the specialists, within their specific areas, and for the generalists, more time for updated knowledge regarding general tasks within their municipality. In case B, there was demand for more specific knowledge of the English language in order to handle all concepts within an authority correctly, to those who did not understand Swedish. In all cases there appeared to be a certain lack of regular feedback from the back office when an issue was resolved.

There are examples of both a highly formalized and rule-based approach (case A), with strict checklists used for the public administrators at the CCs at work, as well as a more informal approach, where the employees mainly are looking for relevant information online and building up their own informal knowledge (case B and D). One CC public administrator comments that, both because the work is not strictly governed by checklists (less formal) and the working climate is very social, you learn from each other within the working group. Working at a CC being both a specialist within a certain area and a generalist in a broader area, made one respondent feel more competent compared to earlier when working at the back office in a specialist role: "I think it's really fun, very social, you learn all the time."

E-administrationInitially there were some technical problems with the new internal ICT tool for registering all incoming issues in almost all cases. There was also an example of a respondent experiencing a certain lack of time to register all issues. This is exemplified by a respondent in case D:

"It's when you are going to enter a case and you don't have time to finish it and calls are coming in the whole time... You have a sentence in mind, you're about to write it down and you don't have time to write more than two letters."

Also, in almost all cases, there was some problem in correctly "labeling" the different issues when registering the issues in a common database.

Reorganization: work situation and anchoring aspects in the view of the public administrators at the back officeThere have been reorganizations within all municipalities with public administrators moved from the back office to the front office (CC), although to a varying extent. For many of the public administrators at the back office, their work has changed as supplier of service due to the implementation of the CC. The number of work tasks transferred from the back-office administration to the CCs varied among the different administrative units within the municipalities. Many simple questions are now answered by the public administrators at the CC, with the result that more public administrators at the back office have more time to work and resolve issues without being disturbed by many telephone calls. At the same time, due to easier access for citizens to contact the municipality, there seems to have been an increase in the number of issues from citizens for public administrators to handle.

In the implementation phase of the CCs there were, however, some negative attitudes from public administrators at the back office in all four municipalities. Some of this seemed to be related to their work situation and a fear of losing work tasks or even jobs. So far no public administrators have been dismissed as a result of the implementation of the CCs. The results also indicate that management in all four municipalities had their main focus on the public administrators at the CCs in the implementation phase, and this lack of attention caused a feeling of inadequacy among some of the public administrators at the back office.

The traditional focus within the municipalities seems to have been on internal processes instead of focusing on the needs of citizens. Therefore when implementing the CCs, all municipalities worked towards a more citizen-centred perspective, although this seemed to be somewhat lacking in Case D. Case B clearly showed the benefits of a long experience of citizen-oriented process working with One-Stop Offices in suburban neighbourhoods. Thus the CC in case B had more integrative effects in the municipal administration, as a respondent from the management argued:

"Even if this process has not been simple, it is much easier here than in other municipalities since we have integrated the values and ideas of integration and putting the citizen in focus. …. The idea has been with us for so long that it is integrated in the organization and the solution of CC was simply the next step".

However, there was a lack in the anchoring of the implementation and reorganization in almost all municipalities. One example is the funding of the CCs, which was made in line with the New Public Management idea of taking the costs where the benefits appear in some of the CCs. Thus the respective unit within the municipality had to "pay" for the e-Government reorganization and CC implementation. In some cases these budget decisions were not sufficiently anchored before the implementation started. Due to easier access to the municipalities for citizens, an increase could be expected in the number of issues from citizens for public administrators to handle, which could lead to a budget problem. However, no additional funds were allocated for this. Instead, the increase was expected to be met within the existing financial framework. This resulted in some units having to "pay" for the implementation of CC with fewer people in the administration fulfilling the same job. This will be exemplified by a respondent from case D:

"[T]his year we have to finance a large part of the activity of the contact centre... and this is a major concern for us... The idea of the CC is that this will be financed within the existing economic framework, otherwise there's no effect."

The management of the division was therefore forced to transfer funds to the CC without being able to reduce costs, as they needed public administrators to perform tasks that could not be transferred to the generalists at the CC. There was for example no special response group for social services at the CC, and the demands of integrity, security and competence were not easy to deal with. There were negative attitudes towards the CC from public administrators at this division due to this situation. This internal financial problem was also highlighted as an anchoring problem by another respondent:

"It's been a big job to create structures around the financing aspect. Actually half a year went into creating the model for supply agreements that we have developed. Obviously, finances are the driving force ..."

This study also implies that there is a need for increased focus on the work of public administrators at the back office. Thus this implementation is a process that benefits from being grounded in values of inclusion and meeting the needs of citizens that includes facilitating a reorganization of back-office procedures in order to optimize the efficiency aspects. Therefore, local context as well as the anchoring of the e-Government policy within the whole organization of the municipalities, seem to be critical aspects. Thus, there is a need for management to better articulate and communicate e-Government strategies related to the transfer of work tasks from the back office to the CCs in order to reduce anxiety among back-office public administrators. Otherwise this may have a negative impact on service to citizens.

To conclude, this study shows that the most significant critical impressions of the implementation of CCs are:

- Deciding on the organization of the CC; whether the administrators should be specialists or generalists or a combination of both.

- Having enough time for regular competence development for the public administrators at the CCs.

- Anchoring the implementation of the CC to all divisions within the whole municipal organization and to decide upon internal financing issues before the reorganization.

- Working for a "citizen-centric" approach.

- Specifying which work processes should be transferred to CC.

4.2 Findings from the citizen perspective

The focus here will be on accessibility and citizen-centred aspects including "customer" approaches when implementing CCs in relation to creating some sort of added value.

AccessibilityAccording to almost all respondents, accessibility to municipal services increased in all cases due to the implementation of the CCs. The e-Government relationship between the public administration and citizens, here referred to as e-services, thus has increased. The use of a single telephone number to all municipal services and the development of more public e-services such as self-service, e.g. citizen assistant and more specific information on the municipal websites, increased citizen accessibility. The hours of operation for municipal service also increased (open all weekdays), although two-thirds of the citizens interviewed were satisfied with the hours of the CC in case D and the others would prefer to have the CC open also on weekends. It has become easier to make personal visits to the municipality through the CCs, even if in cases B and C these are referred to the One-Stop Government Offices instead of to the CCs and in case D the CC will be open for personal visits in an office in the city centre in the near future. However, one respondent in case D argued that there might be a risk for a detour for the citizens when all telephone calls will now be answered at the CC and as generalists they do not have the competence to handle the issue. If the citizen could get in contact with a public administrator at the back office in charge of this issue directly, the citizen might get an immediate answer to the issue.

"…before, they came directly to either a public administrator and then there was an immediate start of the issue, or to someone who actually took care of the issue. But now, I think, with the contact centre it will be a detour."

In all cases except for case A and in one of the CCs in case C, citizens can still call specialized units within public administration (back office) even if there were ambitions to reduce these contacts. However, this study also implies a lack of confidence regarding the CC implementation since some citizens, according to respondents at the back offices, preferred to have direct communication with the administrators at the back office because they have authority to make decisions on the citizens' questions.

Municipality B had a long, almost ideological tradition of dialogue with, and providing services for, their residents, mainly by the implementation of One-Stop Government Offices. This aspect can be seen as contributing to increased access to municipal services as it made it easier to transfer work processes to the CC.

Regarding case D (where the pilot study with the citizens was done), the overall impression was that citizens were satisfied with the increased accessibility to the CC. Eighteen of 21 citizens received answers to their questions immediately upon contacting the CC and the other three almost immediately. Most of the citizens used the telephone to receive local governmental service from the municipality because they wanted to talk to a human being, it was easy, or they were in need of a quick reply. However, there were some who, after talking to the public administrator at the CC, commented that in the future they would try to use the Internet (the municipal website). On the question of whether the citizen used the website or e-services in order to get municipal information or not, the citizen commented: "Not yet, but after this telephone call I will try to do it".

Touch-tone techniqueAll citizens, not just the elderly, except one were very pleased with the simple touch-tone technology with just one choice to make (there was no response group in case D). One respondent commented: "The less choice the better, especially for elderly people, multiple choices is hard for old people."

Another respondent, who was very pleased with the simple touch-tone technology, comments that when there are many different choices, you don't know what to answer or which button to press. Another citizen (who at the time was living abroad) commented that this was very good and made a comparison with the situation in England:

"Much better than when there are multiple choices. Here in England we have more than a hundred choices. It is really tough!"

In Case A and B the touch-tone technique can be problematic for certain groups, especially the elderly, and contribute to less access to the CC. However, this seemed to be less in case B due to One-Stop Government Offices and long experience of communication with citizens. The simple touch-tone technology in Case D contributed to the fact that more citizens (for example those who are unwilling or unable to deal with touch-tone technology) could easily contact the CC and access the municipal service. A similar aspect of including more citizens by increasing their access to municipal services was establishing a special CC solely for issues regarding care of the elderly as in Case C. These groups of citizens did not have to use the touch-tone technology in order to contact specialists in elderly issues.

Citizen-centred aspects and "customer" approachThe establishment of a common citizen-centred concept within the whole organization of municipalities has worked out quite well in all municipalities, even if there were some shortcomings in municipality A (see Bernhard, 2009) and D. In case B, the public administrators in the back office had extensive experience of working with One-Stop Government Offices to which they had previously moved some work processes. This aspect has contributed to a positive citizen-centred development for citizen service. In municipality C, they also worked with this, although one respondent's view was that it could be improved even though municipal management had already decided from the start of the contact centre to hire a person with communication skills to work on consolidating the common citizen-centred concept among the employees.

The way citizens are treated when contacting the CC can be seen as a citizen-centred aspect. The citizens interviewed were very satisfied with the way they were treated by the public administrators at the CC. There was however an opinion from a respondent at the CC that there was a lack in the striving towards citizen-centred perspective from the back office in case D: "[T]hey have too much focus on internal processes, not seeing from a citizen perspective."

In this perspective it is also relevant to discuss the NPM feature to view the citizens as customers. As can be read from Table 1 in case A the name of the CC is "customer service" and the public administrators at CC are named "customer service administrator" which may indicate a view of the citizens as customers rather than citizens with rights and duties. One may then argue that this would be in contrast to "society administrator" (Case B). However with respect to the results in this study, what employees at CC are called does not seem to define their view of citizens. In case B where they are named "society administrators" with ideological values of inclusion and meeting the needs of citizens, the management of the municipality decided that all employees should use the term "customer" to promote increased service-mindedness and treat all citizens as customers who are entitled to receive the best service and ensure that everyone is treated equally.

The registering of all issues from the citizens in one common database at the CCs via a digital registration tool may in a sense be viewed as a citizen-centred aspect. This IT system enabled the production of statistics as well as providing support for public e-services. This statistical information source implies knowledge about the citizens' needs for municipal service. This assumes that the statistics are followed up and evaluated by municipal managers. This also means that it becomes obvious to municipal managers what services citizens need and helps them in localizing the public service. This new knowledge may contribute to citizen governance of the municipal services as their needs have been highlighted; also, the new knowledge is a contribution to ICT-mediated participation in internal municipal development and planning issues. The use of statistics could also be the basis for the continuous professional development of the public administrators at the CC, but this needs to be further analysed.

e-ServicesCitizens sometimes made employees at the CCs aware of deficiencies on the website or pointed out e-services that were difficult to use or unable to use. Thus they contributed to improving the e-Government and municipal administration. It might also be argued that this contributed to more communities of citizens being able to get municipal service, which may be seen as a step towards more effective e-Government. However, the model of the CC suggests that access and ability to use e-services are two components that may be seen as success factors for CCs, although in terms of efficiency, other indicators related to user-centred design frameworks in software engineering have to be considered for assessing efficient CCs.

To conclude, this study show that the most significant impressions of the implementation of CCs from the viewpoint of citizens are:

- There has been an increase in accessibility to municipal service.

- Almost all interviewed citizens were very pleased with a simple touch-tone technology.

- Designating the public administrators "customer service administrators" does not seem to define their view of citizens.

- Registering of all issues from the citizens in a common database may in a sense be viewed as a citizen-centred aspect. This information source implies knowledge about the citizens' needs of municipal service and can be used for planning purposes.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The intent of this study was to provide insights on the implementation of local e-Government in Sweden by studying municipal contact centres. Based on a theoretical discussion of e-Government and NPM in the digital era, this study indicates that the implementation of CCs may be viewed as a result of the theories of NPM in the keywords of efficient public services, introducing market mechanisms and customer orientation.

The first research question addressed how the implementation of the CC had affected the work of the public administrators within the CC as well as those in the back office, in terms of their role as suppliers of public service. The role of the public administrators at the CC as suppliers of services can be described as that they can provide different services, combine them and even bridge different administrative domains from a citizen-centred perspective. However, the study implies that the work of the public administrators within the front office (CC) and back office will be more efficient if more work processes are transferred to the CC, provided that the public administrators at the CC have mandate and knowledge to respond to the issues. Critical aspects related to efficiency are, however, work approaches and competence development possibilities for the public administrators at the CCs.

Further, the results point out that it is vital to anchor the CCs in policy making and within the municipalities before implementation. The CC implementation, including e-services and e-administration, cannot be seen as a separate part of the organization. Although the use of IT is essential for the organizational transformation, the results thus indicate that the organizational settings and internal anchoring are greater constraints than new technology for implementation of local e-Government. The study implies that efficiency and citizen-centred approaches in this redesign of information relationships between the public administration and citizens to create some sort of added value are critical. The redesign appears e.g. in an ambition to bridge the silos of local public administration and shows that there is a need for a process organization as design of technology and organization are interrelated.

This study also implies that there is a need for increased focus on the work of public administrators at the back office. Thus this implementation is a process that benefits from being grounded in values of inclusion and meeting the needs of citizens that includes facilitating a reorganization of back-office procedures in order to optimize the efficiency aspects.

The second research question addressed how the implementation of the CC affected citizens regarding access to public municipal service and "customer" approach. The study indicates that the implementation of CCs and addition of more public e-services contribute to increased access for citizens to public municipal services. Citizens have more communication channels to choose from in order to gain access to municipal service. It might also be argued that the implementation of CCs allows for the use of community informatics which means, according to Gurstein (2007), the application of ICTs for the empowerment of local people and communities. To establish CCs and bring more resources and services to the local community with "one simple path" via the phone, while also allowing physical visits, implies enabling access to municipal services for groups without Internet access as well. On the one hand this is an example of efforts to minimize the digital divide and implies a step towards including more communities of citizens. This is because more citizens seem to come closer to the e-Government; they cross the "threshold". On the other hand the implementation of more e-services should be considered in the light of the digital divide that still exists. It is not only the quantity of e-services that matters. It is still a problem that a number of public e-services are used to a low extent (Goldkuhl, 2007; OECD, 2009). A reason for this may be the quality of the e-services.

Another result is that the registering of all issues from the citizens in a common database may in a sense be viewed as a citizen-centred aspect. This information source implies knowledge about the citizens' needs for municipal service and can be used for planning purposes. This may contribute to increased knowledge about the citizens' needs regarding municipal services. The municipal services could then be localized and adjusted to the citizens' needs (and to different communities of citizens), and hence the production of municipal services would become more citizen-governed than before the implementation of the CCs.

The second part of research question number two addressed the "customer approach" of the implementation. The answer found in this study is that to call the public administrators "customer service administrators" does not seem to define their view of citizens. However, this study does indicate that the implementation of CCs may be viewed as a result of the theories of NPM in the keywords of efficient public services, introducing market mechanisms and customer orientation. On the contrary, a CC may be viewed as localizing municipal public services and combining different services into a local e-Government practice, striving to provide a "holistic" approach to the individual citizen in her local context. However, to explain the need for increased citizen perspective by using the metaphor of customer orientation, in line with the New Public Management paradigm, is to mix two perspectives and may therefore be criticised. There is a difference between being a customer and a citizen. Referring to Minzberg (1996), customers buy products but citizens have rights and the priority for them is more than a customer in the government sector.

To conclude, the introduction of a municipal contact centre - a new organizational form, new tasks and new technical practices - is a new phenomenon within the Swedish municipal e-Government context which may be seen as a practical result of the Swedish e-Government policy. This study does not offer enough evidence of whether the policy objectives in Swedish local e-administration to "have simple, open, accessible, effective and secure eGovernment" have been achieved by implementing CCs, although the findings indicate that the objectives of accessible e-administration have been achieved.

Comparing the casesTo compare these results in terms of benchmarking is, as mentioned above, difficult due to the fact that this local e-Government initiative is a new phenomenon. However, despite differences between the CCs, although they are all defined as being a CC, I will discuss and make comparisons within these four cases in order to analyse if there is a "best practice". The results indicate an overall impression that it is difficult to find a "best practice" due to differences in local conditions. Seen from both the public administrators' as well as from the citizens' perspectives, case C seems to be a good comparison. They have two CCs and four one-stop government offices with one CC solely for elderly issues, a single telephone number and touch tone technique. This is good also in terms of the digital divide. However, compared to other Swedish municipalities, it is not a "best practice" nor representative of most Swedish municipalities, as this is a metropolitan municipality having considerably more financial resources, due to a larger population.

When comparing the three other cases, Case B seems to be a good point of comparison, having both a CC to which several work-processes have been transferred, and five one-stop-government offices at which the citizens can make physical visits and do not need to use touch-tone technique or e-services. This is good in terms of the digital divide. On the other hand, this suburban municipality is not representative due to having many more inhabitants from abroad than most other municipalities. Case A is a municipality that can be viewed as a regional centre in rural area and therefore not representative of most other Swedish municipalities except for similar regional centres. However one may argue that case A and case D are relatively comparable as they both are regional centres, although case D is not situated in a rural area. Case D seems better suited to be compared with from the citizens' view as they have a very simple touch-tone-technique and possibilities for citizens to make physical visits. However, they have only transferred one work-process from the back office to the CC which may be a hindering factor in terms of supplying service to citizens. The results indicate that it is important to be familiar with some common success factors although most of the effectiveness of solutions is contingent upon the specifics of local contexts. This study then disputes the dimension of one-size-fits-all assumptions underlying the idea of "best practice" as a solution.

Final remarks

These results show a need for future study. A highly recommended approach would be to make a nationwide survey, based on randomly selected citizens and public administrators in selected types of municipalities in order to generalize findings about e-Government in Sweden. Furthermore, future studies, should examine how the general public perceives and responds to e-Government services. While a qualitative approach offers depth and useful insight, a quantitative approach should explain and predict why e-Government matters and what factors lead to the effectiveness of e-Government.

Future challenges involve further studying the role and value of statistics on all issues in the CCs in learning and planning perspectives of local e-Government for the management of municipalities. Another suggested research question could be: Do small municipalities have enough resources to implement e-Government initiatives like contact centres? The differences between the implemented CCs could also be further investigated. In what way do they differ? What are the consequences for the citizens as well as for the public administrators? It might be fruitful here to further analyse the potential of ICT-mediated citizen participation.iii

Endnotes

iA related concept to that of contact centre

is a One-Stop Government Office (also named Civic Office)

which was introduced some decades ago and is a common

public service unit (front office) where personnel with

general competencies provide services across levels of

governance, administration, authority and sector. This

sets it apart from a contact centre, as the service

provided to citizens concerns issues not only from the

municipality but instead more than one public authority

or sector, hence the concept "one-stop" (SALAR, 1997;

Björk & Boustedt, 2002). The One-Stop Government

Offices are often implemented in municipalities with a

high degree of inhabitants having roots outside

Sweden.

iiDuring 2009-2011 the author has studied the

implementation of CCs in Swedish municipalities in a

project financed by Swedish Governmental Agency for

Innovation Systems (Vinnova). Swedish Association of

municipalities for joint development of E-services

(Sambruk) was one of three parts. At time for the study

eighty municipalities were members of Sambruk although

just a few of them had implemented CCs (however more and

more municipal CCs are now being implemented or planned

to be).

iiiA suggestion would to be to compare e.g. the potential of Community Informatics as done in a case study in Helsinki by Saad-Sulonen and Horelli (2010).