Research Article

African American Undergraduate Students’ Perceived Welcomeness at a Midsized University Library

Kirstin I. Duffin

Research Support Librarian

Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University

Charleston, Illinois, United States of America

Email: [email protected]

Ellen K. Corrigan

Cataloguing Librarian

Booth Library

Eastern Illinois University

Charleston, Illinois, United States of America

Email: [email protected]

Received: 23 Jan. 2023 Accepted: 12 June 2023

![]() 2023 Duffin

and Corrigan.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Duffin

and Corrigan.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30312

Abstract

Objective – This project assessed African American

students’ feelings of comfort and belonging about engaging with library

resources and services at a public regional comprehensive university in the

midwestern United States.

Methods – This study used an explanatory sequential design.

First, we surveyed degree-seeking African American undergraduates on their

perceived welcomeness regarding the library’s collections and spaces, staff and

users, and atmosphere and marketing. We then recruited focus group participants

from the survey, and in focus group sessions, participants expanded on feedback

provided in the survey, with particular emphasis on their feelings about their

interactions and experiences with the library.

Results – Most students who participated indicated the

library is a place where they felt safe and welcomed, although the library felt

to some like a neutral space rather than a place that actively supported them.

Focus group participants shared several easily implementable suggestions for

making the library a more attractive campus space for African American

students.

Conclusion – Student recommendations will shape the

services we provide for an increasingly diverse student body. Changes to make

the library as physical place more welcoming include exhibiting student artwork

and featuring African American themes in displays. The library as a social

space can become more welcoming in several ways. Hiring a diverse staff and

providing staff training on diversity and equity topics, offering engaging

student opportunities for congregation in the library, and collaborating with

African American student organizations will help to foster a sense of belonging

among these students. Facilitating opportunities for connection will contribute

to African American undergraduates’ academic success.

Introduction

Eastern

Illinois University (EIU) Booth Library’s mission is to collaboratively empower

the intellectual and creative growth of our diverse campus and community. To do

so, we must seek input from voices representative of all our users.

Understanding what African American students need from their academic library

is an understudied topic in the library literature. While some university

libraries have utilized surveys or interviews to garner student input, far

fewer have held focus groups to understand the needs of their underrepresented

student populations (but see, for example: Borrelli et al., 2019; Schaller,

2011). The project summarized here builds on such work, with attention to our

local African American undergraduate population. Results from this project will

help direct library efforts to support student engagement, retention, and

graduation.

EIU

is a public regional comprehensive university with a campus enrollment of just

over 6,500, located in a semi-rural town with a population of 17,286 in which

at least 80% of people identify as White (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Booth

Library is EIU’s only library, situated centrally on campus. One of the seven

core strategies of Booth Library’s 2020–2025 strategic plan is to “Build a

culture that supports diversity and inclusion,” with a goal of emphasizing

intentionality in our efforts (Booth Library, 2020). The demographics of

student enrollment at EIU have shifted over the past 15 years and are projected

to continue becoming more diverse alongside national trends. In the fall of

2021, 35.4% of degree-seeking undergraduate students were from underrepresented

racial groups, as compared to 11.9% of students in 2006 (Eastern Illinois

University, 2021). EIU students identifying as African American have more than

doubled in that time: 7.8% in 2006 to 21.0% in 2021 (Eastern Illinois

University, 2021).

Specifically,

our study investigates these students’ perceptions of the library as a

welcoming environment. We adopt the definition of welcomeness used by Stewart et al. (2019), as drawn from the Oxford

English Dictionary, in which a library user “is ‘gladly received’ and feels

‘allowed/invited to’ make use of academic library spaces, without

microaggressive acts from staff and fellow library users” (p. 20). This study

broadly examines several factors that may influence students’ sense of

welcomeness, from providing resources to meet their information needs to

offering a friendly and safe space for studying and congregating. Insights

gathered from this study will not only enable the library to improve services

to this specific user base but also lay the groundwork for replicating the

study with other defined populations.

Literature Review

Meeting

user needs has long been a focus of librarians, but understanding the needs of

underrepresented populations has only been studied more recently. Whitmire

(1999, 2003) conducted some of the earlier research on the experiences of

African American and other undergraduate students of color in academic

libraries. She found that African American undergraduates use academic library

services and resources more than White undergraduates, which may be facilitated

by library support programs for minority students. External factors influenced

student perceptions, as well. Undergraduate students of color expressed, more

so than White undergraduates, the value of increasing campus diversity both

among employees and students as well as in the curriculum; however, students of

color had a more neutral view of the academic library compared to their White

peers (Whitmire, 2004). Whitmire (2004) encouraged further study on how

libraries can provide a welcoming environment for underrepresented students.

Elteto et al. (2008) surveyed students’ perceptions of the physical library as

a welcoming space at their urban university, with particular interest in

gauging the feelings of students of color. They found that students of color

felt less safe in the library than their White peers and were less likely than

White students to ask for specific improvements to the library, though access

to technology and technical and writing assistance were of more importance to

students of color.

Research

is mixed in reporting African American students’ perceptions of welcomeness in

academic libraries and may depend on the unique history and culture of a

university. In a national survey, Black students indicated a general sense of

feeling welcome at their academic library (Stewart et al., 2019), but campuses

that are or have been predominantly White institutions, and libraries in which

professional staff are primarily White, contribute to an atmosphere in which

African American students may not feel as welcomed and supported as White

students (Chapman et al., 2020; Folk & Overbey, 2019; Stewart et al., 2019).

These researchers noted the historical framing of the academic library often as

a White space (Chapman et al., 2020) and that library employees may carry

implicit biases that influence their interactions with students (Folk &

Overbey, 2019).

Libraries

exist as a physical place and social space, so we must consider both as we

assess students’ perceptions of welcomeness. Wiegand (2011, 2015) has written

about the historic role of the public library both as a civic institution and

community space. Wiegand (2005) encouraged librarians to analyze “the library

in the life of our users” to inform the work we do (p. 61). Undergraduate

students have described the academic library first as a physical structure,

perhaps initially imposing and overwhelming, but they also see it as a

productive space to study and socialize (Kracker & Pollio, 2003; Sare et

al., 2021). The academic library might well do more to promote itself as a

social space that fosters relationships and community (Kim, 2017).

Perceptions of support and belonging within an

academic space and place influence a student’s collegiate experience. This

feeling of connectedness may be more important for students of color, affecting

their grades and selected major (Murphy & Zirkel, 2015; Walton & Cohen,

2007). Those who do not feel welcome are at a disadvantage, academically and

socially. Campus initiatives that provide meaningful social connections have

been shown to help students develop their sense of belonging and community,

influencing academic persistence (Bass, 2023; Brooms, 2018; Murphy et al.,

2020). Library services and programs that foster a welcoming environment can be

part of the campus initiatives that contribute to students’ well-being and

academic success.

While

previous studies on the experiences of Black students in academic libraries

have had a methodological focus on surveying a broad range of students (Elteto

et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2019) or interviewing individual students to gain

a more detailed understanding of the personalized experiences of students (Folk

& Overbey, 2019), focus groups have been suggested as a useful approach to

expand research on student affect of library services (Elteto et al., 2008;

Whitmire, 2006). Focus groups provide a synergy in which participants can build

off of each others’ responses, and they allow the

researcher the ability to clarify and probe responses (Stewart et al., 2009).

Our research combines a survey with follow-up focus groups to explore the

question of welcomeness.

Aims

Our

research objective was to explore to what extent Booth Library is perceived as

a welcoming place for our African American undergraduate students. Through a

survey and follow-up focus groups, Booth Library faculty solicited input from

this underrepresented population regarding their use of library services. We

inquired as to which services are valued by these students in

order to ensure our resources are aligned with supporting their needs.

We probed to understand our blind spots, where we could provide new or better

services and resources to reach unmet student needs. By exploring and

responding to the needs of our African American undergraduate students, Booth

Library will be curating a culture of sustainability that supports the

continuing success of students.

Methods

We

employed two forms of data collection for this study. Our intent was to gather

input from a wide swath of our campus population through a survey and conduct

follow-up focus groups to sustain more in-depth conversations with students,

providing a forum to expand on the thoughts they provided in the survey. Focus

groups encourage a dialogue among students, with participants able to share new

thoughts and ideas after hearing from their peers, and they allow the

researcher to have a more extended conversation and ask follow-up questions to

facilitate researcher understanding of participant responses. A subset of

students who completed the online survey were selected to participate in our

focus groups. This research was approved by the EIU Institutional Review Board

in December 2021.

Survey

Initially,

we planned to use LibQUAL+ for our survey. Upon closer investigation, we found

that LibQUAL+ does not assess user affect at the level of detail for which we

were aiming and so would not meet our assessment needs. As has been previously

argued, evaluation of library services is often a nuanced process that must

take into consideration the context-dependent nature of the service being

assessed (Lilburn, 2017; Seale, 2017). We instead adapted a survey that was

developed by Stewart et al. (2019), which was administered to Black

undergraduate students across the United States. For our study, we tailored

questions to reflect the application of the survey within a single institution

and centred questions around three themes: resources, interactions with people

(employees and users), and atmosphere and outreach.

The

survey was up to 33 questions in length and took about 10–15 minutes to

complete (Appendix A). We employed branch logic to create a survey that was

responsive to students’ experiences. The first question was a screening

question to ensure only African American undergraduate students from EIU

completed the survey. From here, the first part opened with a screening

question to gauge whether the respondent had used Booth Library resources. If

so, they were directed to answer five Likert scale questions (strongly agree to

strongly disagree) about the library’s resources; if not, they were prompted to

respond to an open-ended question about why they hadn’t used the library’s

resources. The second part began with a screening question asking whether the

respondent had interacted with people in Booth Library (employees or users). If

yes, they were asked eight Likert scale questions about their contact with

people in the library; if not, they were asked an open-ended question about why

they had not interacted with people in the library. The third part asked

participants if they had visited Booth Library. If yes, they were asked seven

Likert scale questions about the library’s atmosphere and outreach; if not,

they were asked an open-ended question about why they had not been to the

library, along with four Likert scale questions about the library’s atmosphere

and outreach. All respondents were asked two questions about the amount of time

they have used the library along with an open-ended question about their most

memorable experience at Booth Library. The survey ended with six demographic

questions and an invitation to sign up to participate in our focus groups. For

completing the survey, students could opt in to be entered into a raffle for a

$15 Walmart gift card.

Drafts

of the survey were reviewed by a social science research expert and a college

student affairs research expert, also coordinator of the Making Excellence

Inclusive initiative at EIU, and was pilot tested by three African American

undergraduate students. The survey was sent in the spring of 2022 to 1,217

African American undergraduate students through an email from EIU’s Office of

Inclusion and Academic Engagement, as well as emails sent by leaders of

relevant student organizations (i.e., the Black Student Union, National Pan

Hellenic Council, and EIU’s chapter of the N.A.A.C.P.). A promotional flyer

inviting participation was posted through the Black Student Union account on

Instagram and through Booth Library social media channels (Instagram, Facebook,

and Twitter), where relevant campus and student groups were tagged.

Focus Groups

Focus

group sessions expanded on feedback provided in the survey, with particular

emphasis on participants’ feelings about their interactions and experiences

with Booth Library. Our focus group protocol is in Appendix B.

In order to create a safe, welcoming environment

for participants, previous researchers have recommended that focus group

facilitators and notetakers be of the same race as the population being studied

(Chapman et al., 2020; Folk & Overbey, 2019). It can also be helpful for a

non-library employee to facilitate focus groups, both to serve as a neutral

figure with whom participants can feel open to discuss their positive and

negative experiences and to minimize library employee biases from influencing

outcomes (Becher & Flug, 2005; Wahl et al., 2013).

Understanding

this as the ideal scenario, we had discussed employing two African American

graduate assistants as our moderators with the director of our university’s

Office of Inclusion and Academic Engagement. After receiving a solicitation

from a professor seeking opportunities for graduate students from the College

Student Affairs (CSA) program’s research methods course to gain experience in

applying methodology to a real project on campus, we switched gears. Seeing a

chance to directly advance students’ academic and professional goals, we

offered to take on a team to assist with our study. We were then assigned a

group consisting of one African American and two White students. Because their

course objective was to conduct a qualitative research project, these students

developed the focus group protocol with our recommendations. In reviewing the

survey results together, we collaboratively agreed to focus on students'

socio-emotional experiences with Booth Library to elucidate participants'

perceptions of the library as a welcoming place and how the library can be

improved to be more welcoming.

The

research team planned four 60-minute focus groups, with the aim to have 3–5

students in each group. Potential participants were identified from

self-selected volunteers in the pool of survey respondents. In

an attempt to boost participation, sessions were offered mid-semester in

spring of 2022 across multiple days at different times of day. After

considering several spaces around campus, these sessions were held in the

faculty reading room of Booth Library, because it provided a semi-private space

with ample lighting. All participants received a $25 Walmart gift card.

Demographic information was collected as a written questionnaire at the start

of the focus group. To ensure confidentiality, all participants chose a pseudonym for

themselves. Focus

group discussions began with questions about how participants currently use the

library. Questions then explored participants’ perceptions of representation

within the library. The final questions sought recommendations for improvement

of library services.

Sessions

were audio recorded with participant consent. A CSA graduate student created

full transcripts of the recordings using the free online transcription service

Temi and corrected by hand. CSA graduate students independently reviewed the

transcripts using in vivo coding, a method of qualitative data analysis using

the actual language and terminology spoken by the participants as opposed to

researcher-derived codes. With input from the graduate students, the librarians

identified major themes based on the frequency with which concepts came up in

discussion. Repetition is a common theme-recognition technique (Guest et al.,

2012; Ryan & Bernard, 2003), and we used it to identify recurring topics

that emerged between participants within a focus group and across focus group

sessions.

Results

Survey

We

had 70 respondents to our survey. Of those, 52 were fully completed surveys; 11

were completed through either Part I (Library resources), Part II (Interactions

with people in the library), or Part III (Library atmosphere and outreach); six

were only completed through the initial qualifying question (Are you an EIU

undergraduate student who identifies as African American/Black?); and one

responded “no” to the initial qualifying question. We included in our analyses

the 52 fully completed surveys and the 11 surveys that were fully completed

through Part I, Part II, or Part III, for a response rate of 5.2% (63 of 1,217

students to whom the survey was sent). Responses overall were favorable, with a

few areas noted for improvement.

Demographics

All

respondents were traditional-aged college students between the ages of 17 and

25, with a spread across student classification—freshmen (19%), sophomores

(25%), juniors (25%), and seniors (31%)—and an almost even distribution among a

range of majors (grouped by college and discipline), with slightly higher

responses from STEM majors and just one Education major. By comparison, about

90% of all undergraduate degree-seeking students at EIU are of traditional

college age. Our participants were of slightly higher student classification

than the average EIU undergraduate identifying as African American.

Participants in our study were slightly more likely to be an Arts &

Humanities or Business major and slightly less likely to be an Education,

Social Science, or STEM major as compared to the overall population of EIU

undergraduate students who identify as African American (Eastern Illinois

University, 2021).

More

women than men responded to the survey (83% vs. 17%), and just below half (46%)

were first-generation college students. This compares to 58% women and 42% men

overall at EIU who identify as African American undergraduate students (Eastern

Illinois University, 2021). First-generation enrollment of African American

undergraduates at EIU overall (52%) is slightly higher than our participant

demographic (Eastern Illinois University, 2020). The respondents were frequent

library users, with 92% visiting the library more than once a month (48%

reported visiting weekly and another 25% visiting even more often), and the

most common duration of visit being 1–2 hours (55%) followed by 3–4 hours

(39%). Most EIU students, faculty, and staff responding to our latest patron

satisfaction survey reported physically visiting Booth Library once a week

(54%, or 93 of 171 respondents), followed by once a semester (21%) and once a

day (15%); “more than once a month” was not a response option (Booth Library,

2022).

Library Resources

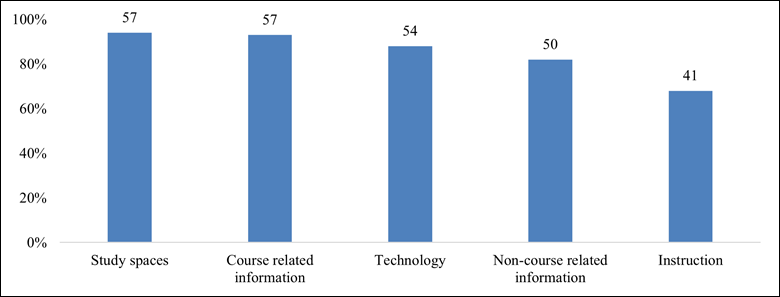

For

this set of questions, the library scored highest on meeting students’ needs

for study spaces and course-related information (93% rating either strongly

agree or somewhat agree on each question), closely followed by technology and

non-course-related information (Figure 1).

Notably,

in response to the open-ended question about their most memorable experience at

Booth Library, 49% stated that studying in the library, individually or in a

group, was particularly memorable for them. Instruction programs (e.g.,

orientations, workshops, and class visits) received the lowest score, with 67%

of those surveyed finding the library’s instructional offerings sufficient for

effective use of its services.

Figure

1

Survey

results for library resources. Percent and number of responses strongly or

somewhat agreeing that needs are met.

Interactions with People in the Library

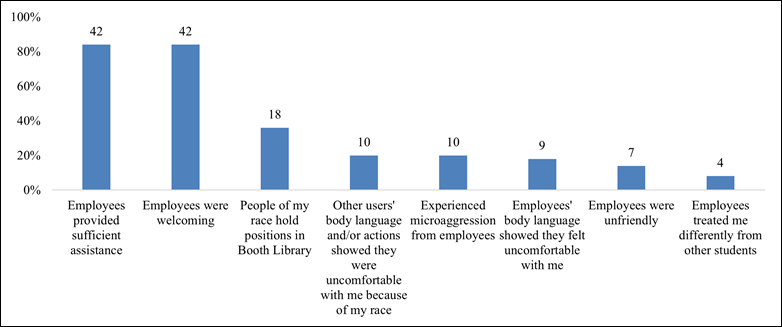

Responses

to questions asking about interactions with people in the library were mostly

positive. Library employees were found to be welcoming (84%) and able to provide assistance (84%, Figure 2). Six of 47 students in

the survey mentioned research and other help from staff as a memorable

experience.

Figure

2

Survey

results for interactions with people in the library (employees and users).

Percent and number of responses strongly or somewhat agreeing.

Sixty

percent of respondents also indicated that library employees did not express

discomfort in their body language or treat them differently from other

students. Another question addressed microaggression, using the Merriam-Webster

(2023) definition of “a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously

or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a

marginalized group, such as a racial minority.” Twenty percent of those

surveyed indicated that they had experienced microaggression from a library

employee; 66% reported not experiencing microaggression. Most interesting is

the range of responses to the question of representation: While 36% agreed that

people of their race held positions in the library, the same percentage of respondents

disagreed with the statement, with the rest neither agreeing nor disagreeing.

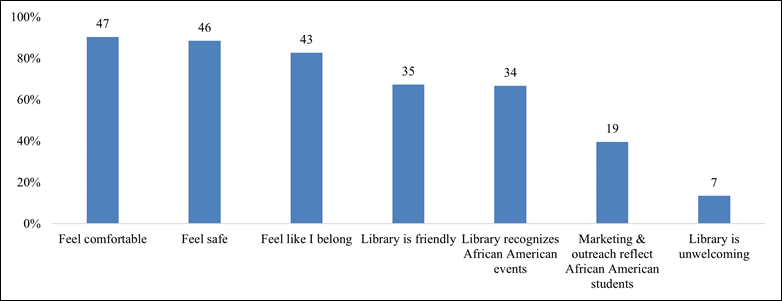

Library Atmosphere and Outreach

In

terms of environment, respondents perceived the library as a welcoming place;

between 80–90% reported feeling personally comfortable, safe, and that they

have a sense of belonging when in the building (Figure 3). Sixty-seven percent

viewed the library as being friendly to African American students

as a whole.

Figure

3

Survey

results for library atmosphere and outreach. Percent and number of responses

strongly or somewhat agreeing.

The

library fared less well on outreach to the African American community on

campus. More respondents agreed (67%) than disagreed (14%) that the library

recognizes African American students through displays and programs, but only

40% saw themselves reflected in marketing efforts, with 23% finding the library

less than adequate in this regard.

Focus Groups

Of

the 40 survey respondents who indicated willingness to participate in follow-up

focus groups, a total of 9 self-selected students attended across 3 sessions.

After gathering demographic data, participants were asked to discuss six

questions probing their perceptions of welcomeness, delving deeper to

illuminate responses from each of the three sections in the survey.

Demographics

Participants

were traditional-aged college students, ranging between 18 and 24 years old.

More seniors (4 of 9 participants) attended, along with 1 freshman, 3

sophomores, and 1 junior. Focus group members represented all academic areas of

our institution: Business (3 participants), STEM (2), Allied Health and Human

Services (1), Arts and Humanities (1), Education (1), and Social Sciences (1).

Eight women and one male student participated, and about half were

first-generation students (5 of 9). Our focus group members were frequent

library users: one visited the library building more than once a week, five

visited weekly, and three visited more than once a month. Participants most commonly reported staying in the library for 1–2 hours

each visit (8 of 9 students); one participant typically spent 3–4 hours.

Themes

The

findings from the focus group sessions largely supported and expanded on our

survey results. From these interviews, five themes emerged.

(1) Use

of Booth Library by participants was chiefly for studying and access to

technology.

Participants

used the library primarily for studying and printing. Five of the nine

participants came to Booth Library for quiet, independent study. Tiffany

explained, “I like to sit [downstairs in the stacks] because I don’t like being

seen in the library…. I just like to be [in] my own zone and, plus,

distractions as well.” Two participants indicated they studied in a group when

they came to the library. One didn’t study in the library but used the

library’s study rooms for student club meetings.

Several

of the participants who used Booth Library almost exclusively as a place for

quiet, focused study occasionally experienced issues related to noise levels

with other users. One student attempted to participate in an online class and

realized her speaking up in class bothered another group studying nearby in the

library. She has since joined class from the more social floor of the library

and has found that to be a solution to her noise volume dilemma.

Access

to technology was another significant reason for coming to the library.

Participants used the computers and, even more so, the printers. Some mentioned

that they or a friend of theirs benefited from the laptop checkout service

available through the library’s Center for Student Innovation, especially when

their personal laptop was malfunctioning and they had an assignment they needed

to complete.

Despite

high ratings in the survey, focus group participants made little to no mention

of information resources. Only one participant talked about her experience with

library instruction. Two participants in separate focus groups mentioned

regularly using the library’s book collection for non-academic reading. Two

participants across our focus groups were appreciative of the snacks that the

Office of Civic Engagement and Volunteerism provided in the library and would

like to see snacks continue to be offered here.

(2) Interactions

with library employees were primarily positive, while feelings surrounding

Booth Library were neutral.

Participant

comments were overwhelmingly positive regarding the assistance they received

from library employees, including student workers. Some mentioned instances of

exceptional help from employees. Michael stated, “The staff members went above

and beyond. If they couldn’t find a book in the system, they would even go,

still, check the shelves to see if the book was there.” Suzy, another

participant, mentioned library instruction:

One of the librarians for our class came

in [and] gave us a tour and showed us how to use the resources in the library.

And I’ve spoken to some other friends…and they said that never happened for

them. So they didn’t really know how to use it, but that’s helped me

personally.

While

participants had generally positive experiences, their overall attitude was

neutral in that they didn’t feel actively supported by the library. Ophelia

observed:

Compared to my other experiences on

campus, I would say that I feel safe in the library, cuz I’ve had bad

experiences out there. But in here it’s just, it’s neutral I’d say. But it’s

still better than bad experiences.

Royal

shared the sentiment, noting, “I haven’t experienced anything negative because

of my race while I’m here. But it’s just like, there’s nothing really to show

that support. There’s no actual, like anything to show appreciation.”

Participants

went on to share ideas for making the library feel more welcoming to African

American students, and these suggestions are explored in the remaining themes

from our focus groups.

(3) Seeing

African American employees and students in Booth Library will attract more

African American students to use the library.

The

focus group discussions elucidated the mixed response to the question of

representation on the survey: Some see student workers of their race, but the

absence of African American faculty and staff is noticeable. In one focus

group, the participants speculated that the applicant pool might not be very

racially diverse for full-time employees in this semi-rural Midwestern

community. They also commented on how seeing more African American students as

users in the library would make the library feel more welcoming. Alice said, “I

would probably come here more, maybe, if I had seen more Black staff here…. Cuz

most of the time when I come here, I don’t really see many Black staff.”

Tiffany also commented:

…I know some people, they be intimidated

to go to the libraries. When I meet some students, I mean us Black students,

it’s because they see there’s not people that look like them in the

library…that’s studying and doing work, as well. So I feel like we just get

that. We bring more of us in the library. And like I said before, it just make

a more comfortable environment.

(4) African

American culture should be celebrated regularly with displays and programming

throughout the year, not just during Black History Month.

Displays

for Black History Month were identified as the library’s chief or only

acknowledgment of their race. One student commented on the survey that the

scarcity of recognition aside from Black History Month is “another reminder

that our history and culture is tolerated, not welcomed.” Focus group

participant Alice added:

It would be nice if they would just do

all through the year and not just only for Black students, but everybody…. It

doesn’t have to be a month in order for them to put

out stuff and really show they support.

These

students would like to see displays celebrating African American culture

throughout the year, or a permanent collection of African American authors that

students could browse. One participant suggested incorporating more modern,

possibly student, artwork in the library. Participants suggested several

interactive social activities to make Booth Library feel more inviting, such as

bringing in comfort animals, having competitions that utilize technology

available in the library, hosting book clubs, partnering with African American

student groups to facilitate study tables, or organizing events on African

American culture for the greater campus community.

(5) Continual

partnerships with African American student groups will help the library gain

input on student needs and interests.

Participants

suggested collaborating with student organizations on promotional efforts and

visiting them where they are, for example at residence hall meetings and

student organization meetings. Participants said they would like to see more

advertising of library resources and events, especially via social media.

Snapchat and Instagram were the most frequently mentioned by name as being

regularly used by students. Social media is preferred over email and flyers

posted in the campus union and residence halls, although they recognize the

usefulness of multiple modes of communication. They also recommended

advertising on portable A-frame sidewalk signs outside the library’s entrances.

Discussion

Similar

to the findings of recent studies (Chapman

et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2019), our participants reported generally

positive experiences with their academic library. Interestingly, despite our

efforts to cast a wide net with recruitment for our study, participants were

chiefly heavy library users, which aligns with participant profiles from

previous research in this area (Folk & Overbey, 2019; Stewart et al.,

2019). Due to a low response rate, our findings cannot be generalized to our

campus population of African American undergraduates. We also were unable to

explore causal connections between feelings of welcomeness and how those

perceptions influence whether and how students use the library. Instead, these

findings can begin to inform future work in continuing to seek feedback from

this student population, as well as shape outreach to additional

underrepresented groups. Participant suggestions—such as for the library to

regularly seek student input, host engaging collaborative events, and diversify

employees—will help to improve a sense of welcomeness for this subset of

students in their use of the library.

Predominant

use of the library by our study’s participants was for meeting personal

academic needs. A subset of participants did indicate, however, that they would

benefit from more instruction on using library resources, a finding in line

with previous research exploring the library needs of students of color (Elteto

et al., 2008). This outcome can serve to embolden our liaison librarians in

their outreach to disciplinary faculty and student support groups, which will

help with library messaging in communicating the value of and need for

information literacy instruction. Like Shoge (2003), students in our study

primarily used the library for studying and accessing technology. Many came for

quiet, focused study, but some felt safest when going to the library with other

African American undergraduates, which mirrors Whitmire’s (2006) finding that

African American students will study with fellow African American students for

companionship, but with White students primarily when they have a study group

or study partner. While libraries have evolved in recent decades into more

social spaces of engagement (Seal, 2015), feedback from participants in our

study underscored the value in continuing to maintain quiet spaces that

students can use for focused study.

In

addition to feeling safer when there was visible diversity among our library

users, students in our research noted that the lack of diversity among library

employees detracted from feelings of welcomeness. Limited racial and ethnic

diversity in the library profession has been reported in earlier studies (e.g.,

Elteto et al., 2008; Stanley, 2007; Welburn, 2010). The Whiteness of the

library profession has implications for the quality of library services, such

as with librarian approachability, responsiveness, and objectivity in reference

transactions as we consider the needs of users of color (Brook et al., 2015).

Despite a growing awareness of the problems associated with the embedded nature

of race in our profession, even with aspirations by many to effect change, the

LIS field has much work to do to course-correct the impact of racism in

libraries and library systems (Crist & Clark/Keefe, 2022;

Schlesselman-Tarango, 2017).

Students

mostly reported having affirming interactions with library employees, although

a noticeable minority reported experiencing microaggression while at the

library, a finding not unique to our study (Folk & Overbey, 2022; Stewart

et al., 2019). However, while participants in our study indicated their

experience with microaggression in their interactions was with library

employees, other researchers reported on microaggression stemming primarily

from interactions with other library users. Our study did not ask specifically

about microaggression from library users, only by library employees. To address

this feedback, our Staff Development Committee organized a staff retreat on

privilege. By providing such trainings within the library, rather than turning

to opportunities open to the campus at large, the discussion can focus on the

unique position of the academic library in students’ lives.

Since

the time of this study, our library hired a First-Year Experience/Student

Success (FYE/SS) Librarian. This new position allows us to better leverage

relationships with students beyond their academic pursuits, an area where the

traditional subject liaison model can fall short. A significant role of the

FYE/SS Librarian is to foster connections between student groups with an

emphasis on promoting diversity and inclusion in our library services. Our

FYE/SS Librarian is collaborating with student groups to develop book displays

that are relevant to our students. We have incorporated feedback from this

study to develop library events that are more welcoming to African American

students, such as creating events that are team-based and competitive, which have

attracted racially diverse participation. As well, supported by the

recommendation of our study’s participants, our FYE/SS Librarian has launched

our first formal student advisory group, comprised of members representing our

diverse student population, in order to seek

continuous input from our stakeholders.

While

library experiences were primarily positive, focus group participants shared

that our library felt like a neutral place for them, and they expressed a

desire for more proactive efforts to affirm the library’s support and

appreciation of underrepresented students. This is in line with past research

in which Black students identified the academic library and its services as

neutral territory (Chapman et al., 2020; Folk & Overbey, 2022), an outcome

that marks libraries as “complicit in their silence” (Chapman et al., 2020, p.

12). Displays and programming celebrating African American culture, along with

more diverse representation in the library’s marketing materials, will foster

efforts to make the library a “third place” in the lives of these students

(Oldenburg, 1997; Whitmire, 2004). Affirming this study’s results, the library

has contributed to the development of, and now hosts, Race Chat events, which

are open forums for the campus community that use reflective structured

dialogue to discuss lived experiences and better understand participants’

views.

We

thought we might hear more mixed feedback from participants, since it is common

to hear both strong positive and strong negative feedback when soliciting

suggestions for improvement, so we felt encouraged that participants had

considerably more positive experiences to convey. Our study did not have the

reach we were hoping, and it is possible that students who have significant

negative perceptions of the library did not contribute to our study. As we

formulated this research project, we were eager to be able to implement any

recommended changes, in order to instill trust between

participants and their library. We were concerned that the suggestions we would

receive would be resource prohibitive to implement. Instead, students offered

very achievable solutions to make the library more welcoming. Future outreach

to African American students who are non-library users, alongside continuing

conversations with users, will enrich library progress toward serving as a

welcoming campus resource for our African American students.

This

study adds to the existing literature on African American students’ perceptions

of feeling welcome in academic libraries by detailing the experiences of

undergraduates at a semi-rural, regional comprehensive university. Our use of

focus groups as a methodology builds on previous studies that have explored

African American student experiences with their academic libraries via surveys

or one-on-one interviews (Elteto et al., 2008; Folk & Overbey, 2019;

Stewart et al., 2019). Focus groups allowed our participants to consider the

experiences of their peers and develop shared recommendations to improve

library services.

Limitations

Sample

size was a limitation of both the survey and the focus groups. For the survey,

only 63 complete or partial responses were received from soliciting a potential

audience of more than 1,200 African American undergraduate students. Of the 40

survey respondents who indicated willingness to participate in a focus group,

only 18 volunteered when contacted by our CSA graduate students, and of those,

only nine attended the sessions. Also, with only one survey respondent

indicating they had not used Booth Library resources or services, we were

unable to solicit representative feedback from non-library users in this study.

In

all aspects of these limitations, a higher rate of participation might have

been achieved by developing stronger interpersonal relationships between the

study’s researchers (us) and campus leaders we identified to help recruit

participants. Our primary line of connection with many of our campus leaders

was via email. While all were willing to share communications about our study,

they may have taken a more active role in recruitment had we met each leader in

person during the early stages of our outreach. This might assist, in particular, with recruiting non-library users. Indeed,

non-library users were a group from whom we had hoped the most to hear, to gain

their valuable perspectives as to how the library can be made a more welcoming

place for their academic and personal pursuits.

Future Research

The

results from our study establish a starting point for future research. We

recommend involving and collaborating with members of the relevant student

organizations from the start and throughout the process to achieve a richer

outcome. Building relationships with these student groups would also help with

promoting participation. As we largely relied on email and flyers to reach

prospective participants, we further recommend making greater use of social

media to publicize the study.

Conclusion

This

study contributes to the growing body of research on African American student

experiences in the academic library. While the response rate to our survey was

low, participants reported mostly positive feelings associated with their use

of Booth Library. Focus group discussions allowed participants to share their

experiences and build off one another’s ideas in providing input. The academic

library can become a more welcoming physical place for these undergraduates by

featuring student artwork and spotlighting African American themes in displays

throughout the year. The academic library as a social space can be more

welcoming in several ways. Hiring and retaining racially diverse employees will

improve visible representation, and ensuring employees are trained on topics of

diversity and equity will increase staff awareness. As well, the library should

host events that celebrate African American culture and create opportunities

for congregation such as through competitive and group activities. The library

should be proactive in developing relationships with African American student

organizations, collaborating with them in developing exhibits and events and

continuously seeking their feedback. Facilitating these opportunities for

connection will improve the overall college experience for African American

undergraduates and encourage their academic success. Future studies should

begin by building strong relationships with leaders of African American social

groups on campus in order to increase the recruitment of

research participants.

By

involving students in the library’s planning process, academic libraries are

better able to strategically address the voiced desires and unmet needs of

their African American student users. While making strides to resolve the more

systemic issues of racism in the library field, not the least of which is

helping to create opportunities to diversify the profession, academic

librarians can endeavor to make the library a more welcoming space for African

American students.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish

to thank Dr. Catherine Polydore for her feedback on survey design and Dr.

Michael Gillespie for his assistance with survey design and data analysis. The

authors acknowledge Dionne Lipscomb, Jacob Mueller, and Madeline Reiher for

their help in designing and leading the focus groups in this study. We

thank Don Jason, Sarah L. Johnson, and Amy Odwarka

for

their valuable feedback on drafts of this article. This

study was supported by the EIU Foundation’s Redden Fund

for the Improvement of Undergraduate Instruction.

Author Contributions

Kirstin Duffin:

Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (equal),

Methodology (equal), Project administration, Visualization (supporting),

Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal) Ellen

Corrigan: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (supporting),

Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing –

original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Bass,

S. A. (2023). Redesigning college for student success: Holistic education,

inclusive personalized support, and responsive initiatives for a digitally

immersed, stressed, and diverse student body. Change: The Magazine of Higher

Learning, 55(2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2023.2180273

Becher,

M. L., & Flug, J. L. (2005). Using student focus groups to inform library

planning and marketing. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 12(1–2),

1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J106v12n01_01

Booth

Library. (2020). 2020–2025 strategic plan. Eastern Illinois University. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_strategic_plan/1/

Booth

Library. (2022). Library patron

satisfaction survey [Unpublished data]. Eastern Illinois University.

Borrelli,

S., Su, C., Selden, S., & Munip, L. (2019). Investigating first-generation

students’ perceptions of library personnel: A case study from the Penn State

University Libraries. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 20(1),

27–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-07-2018-0018

Brook,

F., Ellenwood, D., & Lazzaro, A. E. (2015). In pursuit of antiracist social

justice: Denaturalizing Whiteness in the academic library. Library Trends,

64(2), 246–284. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2015.0048

Brooms,

D. R. (2018). Exploring Black Male Initiative programs: Potential and

possibilities for supporting Black male success in college. Journal of Negro

Education, 87(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.87.1.0059

Chapman,

J., Daly, E., Forte, A., King, I., Yang, B. W., & Zabala, P. (2020). Understanding

the experiences and needs of Black students at Duke. Duke University

Libraries. https://hdl.handle.net/10161/20753

Crist,

E. A., & Clark/Keefe, K. (2022). A critical phenomenology of whiteness in

academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(4),

102557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102557

Eastern

Illinois University. (2020). Eastern

Illinois University key publication facts. https://www.eiu.edu/ir/2020%20eiu%20Key%20Publication%20Facts.pdf

Eastern Illinois University. (2021). Fall

enrollment tables. https://www.eiu.edu/ir/Fall%202021%20FES%20Part%20II.pdf

Elteto,

S., Jackson, R. M., & Lim, A. (2008). Is the library a “welcoming space”?

An urban academic library and diverse student experiences. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 8(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0008

Folk,

A. L., & Overbey, T. (2019). Narratives of (dis)engagement: Exploring

Black/African-American undergraduate students’ experiences with libraries. In

D. M. Mueller (Ed.), Recasting the narrative: The proceedings of the ACRL

2019 Conference, April 10–13, 2019, Cleveland, Ohio (pp. 375–383).

Association of College and Research Libraries. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2019/NarrativesofDisEngagement.pdf

Folk,

A. L., & Overbey, T. (2022). Narratives of (dis)engagement: Exploring

Black and African American students’ experiences in libraries. ALA

Editions.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012).

Applied thematic analysis. Sage.

Kim,

J.-A. (2017). User perception and use of the academic library: A correlation

analysis. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(3), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.03.002

Kracker,

J., & Pollio, H. R. (2003). The experience of libraries across time:

Thematic analysis of undergraduate recollections of library experiences. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(12),

1104–1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10309

Lilburn,

J. (2017). Ideology and audit culture: Standardized service quality surveys in

academic libraries. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(1),

91–110. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0006

Merriam-Webster.

(2023). Microaggression. In Merriam-Webster.com

dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/microaggression

Murphy,

M. C., Gopalan, M., Carter, E. R., Emerson, K. T. U., Bottoms, B. L., &

Walton, G. M. (2020). A customized belonging intervention improves retention of

socially disadvantaged students at a broad-access university. Science

Advances, 6(29), eaba4677. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba4677

Murphy,

M. C., & Zirkel, S. (2015). Race and belonging in school: How anticipated

and experienced belonging affect choice, persistence, and performance. Teachers

College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 117(12),

1–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511701204

Oldenburg, R. (1997). The great good place: Cafés,

coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars,

hangouts, and how they get you through the day (2nd ed.). Marlowe & Co.

Ryan,

G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field

Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

Sare,

L., Bales, S., & Budzise-Weaver, T. (2021). The quiet agora: Undergraduate

perceptions of the academic library. College & Undergraduate Libraries,

28(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2020.1850384

Schaller,

S. (2011). Information needs of LGBTQ college students. Libri: International

Journal of Libraries & Information Services, 61(2), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1515/libr.2011.009

Schlesselman-Tarango,

G. (Ed.). (2017). Topographies of Whiteness: Mapping Whiteness in library

and information science. Library Juice Press.

Seal,

R. A. (2015). Library spaces in the 21st century: Meeting the challenges of

user needs for information, technology, and expertise. Library Management,

36(8/9), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-11-2014-0136

Seale,

M. (2017). Efficiency or jagged edges: Resisting neoliberal logics of

assessment. Progressive Librarian, 46, 140–145. http://www.progressivelibrariansguild.org/PL/PL46/140seale.pdf

Shoge,

R. C. (2003). The library as place in the lives of African Americans. In Learning

to make a difference: The proceedings of the ACRL 11th National Conference,

April 10–13, 2003, Charlotte, North Carolina. Association of College and

Research Libraries. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/17608

Stanley,

M. J. (2007). Case study: Where is the diversity? Focus groups on how students

view the face of librarianship. Library Administration & Management,

21(2), 83–89. https://hdl.handle.net/1805/1440

Stewart,

B., Ju, B., & Kendrick, K. D. (2019). Racial climate and inclusiveness in

academic libraries: Perceptions of welcomeness among Black college students. The

Library Quarterly, 89(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/700661

Stewart, D. W., Shamdasani, P. N., & Rook, D. W.

(2009). Group depth interviews: Focus group research. In L. Bickman & D. J.

Rog (Eds.), The Sage handbook of applied social research methods (2nd

ed., pp. 589–616). Sage.

U.S.

Census Bureau. (2021). 2020 decennial

census redistricting data (P.L. 94-171): Table P1: Race: Charleston city,

Illinois. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://data.census.gov/table?q=population+in+Charleston,+Illinois+in+2020&tid=DECENNIALPL2020.P1

Wahl,

D., Avery, B., & Henry, L. (2013). Studying distance students: Methods,

findings, actions. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance

Learning, 7(1–2), 183–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2012.705656

Walton,

G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit,

and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1),

82–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Welburn,

W. C. (2010). Creating inclusive communities: Diversity and the responses of

academic libraries. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 10(3),

355–363. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0107

Whitmire,

E. (1999). Racial differences in the academic library experiences of

undergraduates. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 25(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80173-6

Whitmire,

E. (2003). Cultural diversity and undergraduates’ academic library use. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 29(3), 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(03)00019-3

Whitmire,

E. (2004). The campus racial climate and undergraduates’ perceptions of the

academic library. portal: Libraries & the Academy, 4(3),

363–378. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0057

Whitmire,

E. (2006). African American undergraduates and the university academic library.

Journal of Negro Education, 75(1), 60–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40026504

Wiegand,

W. A. (2005). Critiquing the curriculum. American Libraries, 36(1),

58, 60–61.

Wiegand,

W. A. (2011). Main Street public library: Community places and reading

spaces in the rural heartland, 1876-1956. University of Iowa Press.

Wiegand,

W. A. (2015). Part of our lives: A people’s history of the American public

library. Oxford University Press.

Appendix A

Survey

Questions

African

American/Black Undergraduate Perceptions of Booth Library as a Welcoming Place

Are you an EIU

undergraduate student who identifies as African American/Black?

“Yes” – Move on

to survey.

“No” – Thank

participant for their time and exit survey.

Your responses

will be kept anonymous. If you wish to participate in further research on this

topic, you will have the option to add your name and e-mail at the end of this

survey.

Part I:

Have you used Booth Library resources? (For example: books, articles,

technology, study spaces)

“Yes” – Move on

to question block.

“No” – Why have

you not used Booth Library resources? [open text response]

For this set of

questions, think about the resources available at Booth Library in relation to

your race.

Response

options: Strongly agree / Somewhat agree / Neither agree nor disagree /

Somewhat disagree / Strongly disagree / Not applicable

- Booth

Library provides information resources that meet my course-related

needs (via books, journals, databases, etc.).

- Booth

Library provides information resources that meet my non-course-related

information needs (for example, news/current events, health, career,

leisure).

- Booth

Library provides sufficient instruction programs (for example class

visits, workshops, orientations) for effective use of its services.

- Booth

Library provides sufficient access to technology for my needs (for example

computers, software programs, printers, etc.).

- Booth

Library provides adequate study spaces.

Part II:

Have you interacted with people in Booth Library? (Library employees or library

users)

“Yes” – Move on

to question block.

“No” – Why have you

not interacted with library employees or library users in Booth Library? [open

text response]

For this set of

questions, think about your interactions with people in Booth Library in

relation to your race.

Response

options: Strongly agree / Somewhat agree / Neither agree nor disagree /

Somewhat disagree / Strongly disagree / Not applicable

- Library

employees provided sufficient assistance to meet my needs.

- Library

employees were welcoming toward me.

- Library

employees were unfriendly to me.

- Library

employees’ body language showed they felt uncomfortable with me.

- Library

employees treated me differently from other students.

- I

have experienced microaggression* from library employees.

*Microaggression

is defined as a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or

unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a

marginalized group (such as a racial minority).

- Other

library users’ body language and/or actions showed they were uncomfortable

with me because of my race.

- People

of my race hold positions in Booth Library.

Part III:

Have you visited Booth Library?

“Yes” – Move on

to question block.

“No” – Why have

you not been to Booth Library? [open text response] AND Questions 17–20 (see

below).

For this set of

questions, think about the atmosphere at Booth Library in relation to your

race.

Response

options: Strongly agree / Somewhat agree / Neither agree nor disagree /

Somewhat disagree / Strongly disagree / Not applicable

- I

feel like I belong when I’m at Booth Library.

- When

I walk into Booth Library, I feel comfortable.

- I

feel safe when visiting Booth Library.

- I

feel Booth Library, as a whole, is unwelcoming to

African American/Black students.

- I

feel Booth Library, as a whole, is friendly to

African American/Black students.

- Booth

Library’s marketing and outreach materials reflect African American/Black

students.

- Booth

Library recognizes African American/Black oriented events and activities

(for example: library displays or exhibits around Black History month,

#BlackLivesMatter, Black authors and researchers, etc.).

For this set of

questions, think about your use of Booth Library.

- How

frequently, on average, do you visit Booth Library?

Daily

More

than once a week

Weekly

More

than once a month

Once

or twice a semester

Never

- What

is the typical duration of your library visit?

Less

than 1 hour

1-2

hours

3-4

hours

5-6

hours

More

than 6 hours

Not

applicable

- What

is your most memorable experience at Booth Library?

[open text

response]

For this final

set of questions, please tell us more about yourself.

- I

identify as:

Female

Male

Non-binary

I

prefer to self-describe (please specify): [open text response]

I

prefer not to answer

- My

age is:

[open

text response]

- I

am a first-generation college student:

Yes

No

- Based

on my credit hours, my class rank is:

Freshman

(0-29 credit hours)

Sophomore

(30-59 credit hours)

Junior

(60-89 credit hours)

Senior

(90 or more credit hours)

- My

overall GPA is:

[open

text response]

- Broadly

speaking, my intended major falls within (select all that apply):

Allied

Health & Human Services

Arts

& Humanities

Business

Education

Social

Sciences

Sciences,

Technology & Math

Undecided

Other/Unsure

(please specify): [open text response]

- If

you are interested in participating in a 60-minute group discussion on

this topic, please include your name and email below. If chosen, we will

reach out to you later this month to schedule the session. Discussion

group participants will receive a $25 gift card as compensation for their

time.

Your

name: [open text response]

Your

email: [open text response]

- Would

you like to enter the raffle to win a $15 Walmart gift card?

“Yes”

– Redirect to raffle survey.

“No”

– Thank participant for their time and exit survey.

Raffle survey:

If you would

like to be entered into a drawing to win one of twenty $15 Walmart gift cards,

please include your contact information below.

Your name: [open

text response]

Your email:

[open text response]

End survey.

Appendix B

Focus

Group Protocol

Participants

arrive and are given a pseudonym, gift card, and directed into the interview

room.

Participants are

welcomed and made aware that the focus group will be recorded and stored on an

EIU password-protected server. Informed consent paperwork is explained and

participants are reminded of no penalty to withdraw. Participants are informed

of the process if they opt to withdraw from the focus group. Last-minute

concerns or questions are addressed, and the focus group begins.

Pre-question:

- Do

we have your permission to record this interview?

Demographic

questions (asked via written questionnaire):

- What

are your preferred pronouns?

- What

is your self-identified gender?

- Are

you a first-generation student?

- What

is your current academic classification based on credit hours?

- What

is your current intended major?

- What

is your self-identified ethnicity?

- Why

did you choose to attend this institution?

Booth Library

perceived welcomeness questions:

- Can

you describe how you use Booth Library?

- Can

you describe your experiences with Booth Library? Were they positive or

negative? Can you identify the causes for that outcome?

- Can

you describe your interactions with Booth Library staff? How did you feel

leaving that interaction?

- Can

you describe how you feel when you are in Booth Library? Do you feel

represented? Why or why not?

- Can

you describe one area of Booth Library you feel can be improved upon? Why

did you pick that area?

- Do

you feel Booth Library supports Black students? Why or why not? Can you

provide examples personal to you?

Focus group

concludes – Participants are thanked. Recording is saved and filed on

password-protected server.