Research Article

May I borrow a Stapler? Is this all Students Ask at the Service Desk in a University Library?

Liv Inger Lamøy

Research librarian

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

University Library

Trondheim, Norway

E-mail: [email protected]

Astrid Kilvik

Senior Research Librarian

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

University Library

Trondheim, Norway

E-mail: [email protected]

Received: 20 Nov. 2020 Accepted: 7 Jun. 2021

![]() 2021 Lamøy and Kilvik. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Lamøy and Kilvik. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29883

Abstract

Objective

-

The objective of the study is to increase the knowledge

about what questions students ask at the library desk and what the purpose is

of their use of the desk. Our focus has been on the physical meetings with the

students. The aim is to contribute to the discussion on the future development

of the library service desk.

Methods

-

We recorded questions asked at the desks to explore how students use the library service desks. The

recording, where library staff sorted questions into predefined categories,

took place over four weeks between the years 2017–2018.

Results

-

Our recording showed that 63% of the questions asked at the library service desks were about loan services, document

delivery, and access to physical and electronic collections. Practical things

such as opening hours, lost and found items, and the location of the group

study rooms, accounted for 16% of questions. Questions about information

technology (IT) made up 8% of questions. Finally, the results showed that 8% of

the questions from the four weeks of counting were counselling and guidance

questions, and 2% were about literature lists, reference management, and

reference management tools. We found more questions about counselling and

guidance in the spring weeks and more practical questions in the fall. We did

not find any clear connection between the number of questions and the size of

the branch libraries.

Conclusion

–

By conducting this study, we have learned more about

why students use the library desk. Our study shows that students come to the

library desk to ask about a lot more than just borrowing staples. The

results from the study will inform the development of the library desk service

going forward.

Introduction

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

is the largest university in Norway today. NTNU specializes in science and

technology, and offers a variety of programs of professional study, along with

broad range of academic disciplines. NTNU University Library is a public

scientific library, with branch libraries located on several campuses. The main

objective of the library is to support research and education, and students and

staff are its primary users. The branch libraries differ in terms of collection

size, whether they have special collections or not, and how many faculties and

departments they provide services to. Some of the branch libraries have only

one employee while the largest ones have up to 15. There are service desks at

all branch libraries. Most of the libraries have only one desk where patrons

can ask a variety of questions about circulation, access to electronic and

print collections, literature searching, reference management and tools, IT,

and more. Questions are answered at the desks or forwarded to specialists in

the library. One of the larger branch libraries has two desks, one for

circulation questions and one for counselling and guidance questions.

For some years, the library desk has been the subject

of discussions, valuations, and musings about what to do with it, how to staff

it, and how to organize it. The fight for attention is hard, and other areas,

such as digital content, new user demands, web-based services, and new

self-service solutions, have for quite a long period been the centre of

attention in libraries in Norwegian institutions of higher education. At the

same time, the anecdotes about the library desk are very much alive and may

sound like: "I just

get questions about printers and group study rooms", "The

students don’t make use of the desks during the examination period",

"The only thing they ask for at the desk is to borrow the stapler".

We began to wonder if the anecdotes reflect today's reality. We have extensive

experience working at the service desks and these descriptions do not

accurately describe what we have seen.

There

are several international studies on topics related to the library desk

service, recording, and categorizing of inquiries. (Gerlich

& Berard, 2007; Henry & Neville, 2008; Katz,

2002; LeMire et al., 2016, Lenkart

& Yu, 2017; Radford & Connaway, 2013; Ryan,

2008; Warner, 2001). But so far, there is a lack of Norwegian data in the

field. To increase our knowledge about what really goes on at

the library desk in a large Norwegian multi-branch university library, we launched a project called TREFF (the

"Desk-project")[1]

in 2017. The National Library of Norway provided financial support for the

project. The start of this project was to map the questions received at the

desks in all the university's branch libraries. Our focus has been on physical

meetings with students, and we describe and discuss the process and results in the following article.

Literature Review

To increase

knowledge about what students ask at our university

library´s service desks, we analyzed their questions. To facilitate the

analysis, we sought out literature about similar recording projects in other

libraries. We had two objectives for our literature search. The first was to

find a suitable recording form. The second objective was to explore the

findings in previous studies, to place our study in a wider scholarly context.

Because our project included all branch libraries, we needed the recording

method to be as simple as possible. In our search, we did not come across any

Norwegian studies, but we discovered several international ones.

According to the

literature, questions asked at library desks are assigned different

classifications as a means of recording the activity. Katz (2002) used the

traditional categories for classification of reference questions: direction,

ready reference, specific-search questions, and research. In 2001, East

Carolina University was in the process of changing their reference desk

organization to a "single point of service", and they saw a need to

re-examine how they record reference transaction statistics (Warner, 2001).

Warner created a classification system based on the resources required to

answer the question: non-resource-based (Level I), skill-based (Level II),

strategy-based (Level III), and consultation (Level IV). One of the benefits of

using this system was that it identified, as early as possible in the

encounter, which library staff member should answer the question. The findings

from the collection of statistics using the Warner classification showed that

80% of the questions from the new service desk fell into Levels I and II and

could be answered by students or technicians, while 20% fell into Levels III

and IV and would usually be referred to a reference librarian. Henry and

Neville (2008) collected questions received at the reference desk and tested

both Katz’s resource- and time-based categories and Warner’s resource-based

categories. The results showed that the directional or non-resource-based

questions accounted for 50% or more of the total, the skill-based or ready

reference questions 30-40 %, and strategy-based or specific search questions

less than 10%. They concluded that Warner’s system appeared more applicable,

but also that value can be added if time-of-day and time-of-semester activity

is included. In a holistic approach to evaluating in-person, email, and chat

reference transactions, LeMire et al. (2016)

considered Warner’s and Katz’s scales and the READ scale. The latter is a six-point

scale developed to record the skills, knowledge, techniques, and tools used by

the librarian during a reference transaction. On this scale, level 1 questions

require the least amount of effort and knowledge, while level 6 require the

most effort and are time-expended inquiries. Time dedicated to the transaction

is also recognized in the READ scale (Gerlich & Berard, 2007).

LeMire et al. (2016) chose not to use any of the existing

scales because they tended to pre-assign higher value to in-depth, subject-oriented

reference questions. The authors believed that, "…even 'simple' question

types can give patrons valuable help and can turn into complex information

searches" (p. 231). In addition, the existing scales do not consider

questions in new areas, like open-access publishing, maker spaces, and so on.

The codebook developed by LeMire et al. (2016)

consists of nine broad categories: Library Information and Policy,

Circulation/Borrowing/Reserves, Research and Reference, Locate Materials, SFX/EZProxy/Off-Campus Access, Technology,

Print/Scan/Copy/Duplication, Feedback and Other. The results of their

evaluation of reference desk, email, and chat transactions in a shared service

point showed that 22% of the questions were in the category Library Information

and Policy, 18% were in Circulation/Borrowing/Reserves, 16% in Research and

Reference, 15% in Locate Materials, and 17% were in the print, technology,

feedback and other categories. More detailed classifications have also been

developed. A study of the cost-effectiveness of staffing a traditional

reference desk in a university library divided 6,959 reference desk

transactions into four major categories: directional, look-up, reference, and

technology (Ryan, 2008). The questions came in person, by phone, or by email.

The reference category was subdivided further into eight categories: catalogue

search, citation help, database help, guide to correct database(s), personal

knowledge or referral, quick internet, research, and serials solutions. The

results from Ryan's study (2008) showed that 36.3% of the questions were

non-informational (did not refer to the collection) or were ‘machine’

transactions (printer and copy issues). Directional questions about the

collections accounted for 15.4% and quick lookups for 9%. Of these questions,

12.4% were about technology (excel, logins, passwords, network), 26.8% were in

the reference category, of which 11% were research questions.

Radford and Connaway (2013) analyzed live chat and instant messaging

(IM) questions and used the categories of subject search, ready reference

procedural, no question, holdings, research, inappropriate directional, and

readers’ advisory. The results showed that subject search question frequency

had sunk and that there was a shift towards more procedural questions. In their

study, Lenkart and Yu (2017) examined 66,638

in-person, email, and phone transactions from 5 specialized and 2 general

reference service points at the University of Illinois Library. The researchers

found that 30.9% of the total number of transactions were directional, 18.1%

were about library policies and services, 22.8% were questions about library

materials and 6.3% were inquiries for research assistance. In addition, 2.5%

were ready reference and 11.6% were related to things like printers, scanners,

software and so on.

Aims

In

this study, we aimed to increase our knowledge about what questions students

ask at the library desk in a large Norwegian university. What is the purpose of

the students’ use of the desk? Our focus has been on physical meetings with the

students. The research question guiding this study has been: What

questions do the students ask at the library service desks in a large,

multi-branch library at a Norwegian university? By mapping the desk activity

and investigating students' inquiries at all branch libraries, we hope to

contribute to the discussion on the future development of the library service

desk.

Methods

To

understand how students use the library service desks,

we recorded the questions they asked at the desks. We started out searching for

a suitable recording form, but the forms we found in the literature were too

complex for our project. For instance, we could not use forms that included

considerations about the complexity of each question or time spent to answer (Gerlich & Berard, 2007; Katz,

2002; Warner, 2001; Ryan, 2008). Because our recording process would include

different staff members in several branch libraries, we needed the form to be

as simple as possible. The more variables the greater the chance of inaccurate

recordings, which could lead to errors in the data. For this reason, we decided

not to use any of the forms presented in the literature and instead developed a

new recording form for this study (Appendix).

From

the literature review, we found inspiration for subject categories (LeMire et al., 2016; Lenkart

& Yu, 2017; Radford & Connaway, 2013; Ryan,

2008), but we chose to use terminology that would fit into the context of a

large Norwegian university library and that our colleagues at the service desks

would be familiar with. We decided to use the following categories: Collection

and Access, Counselling/Guidance[2],

Citing and Referencing, Loan, Practical questions[3], IT

questions, and Other questions[4].

Although the form had to be simple, like Henry & Neville (2008), we chose

to include time-of-day as a parameter, as this would add valuable information

without complicating the recording process. The time periods we used were:

opening hours until 12:00p.m., from 12:00p.m. until 3:30p.m. and from 3:30p.m.

until closing time.

The

project members reviewed and tested the first draft of the recording form and

the subject categories. We also carried out a pilot at a couple of branch

libraries in advance of the first recording week. The form worked well, but

more clarifying examples were needed under some of the categories. We pointed

out that questions about the location of study rooms, auditoriums, cafés, and

so on were to be recorded in the Practical category. We clarified that the

Other category should be used for questions about exams, grades, and other

similar topics.

We

observed five hours’ worth of interactions between students and desk staff in

four of the branch libraries during the first recording week. The observations

served as a validation of the recording forms and confirmed that the forms

worked well. Therefore, no further adjustments were needed. Eventually, we

found a coincidence of types and distribution of questions in the observations

and in the recording weeks.

Student

activities vary throughout the academic year. In some periods, they are busy

with exam reading, while in others, they are writing assignments. To get a good

distribution of the recording weeks throughout the academic year, the first

recording took place in November 2017, the rest were conducted in 2018

(February, April, and September) so that these different phases could be

compared.

The

recording of questions was conducted by the desk staff in all 14 branches of

our university library. We notified colleagues ahead of the recording weeks and

gave clear instructions on how to record. We stated that only questions from

students were to be recorded (including students from other universities). Since

our study dealt with physical meetings with students, questions by email or

phone should not be counted. The libraries used one form per day and recorded

all individual questions in the correct category. There could be several

questions per inquiry and all questions were recorded. The students were

notified of the recording activities by placards placed on the desks. Questions

were recorded in the predefined categories with one tally mark for each

question. We used paper forms and collected the forms after each

recording week. The total results were transferred into Excel for further

processing.

Results

In this study, in-person questions from students at

the library service desks were collected through four different weeks spread

throughout the academic year from November 2017 to September 2018. During this period,

a total of 9,683 questions were recorded in the different 14 branch libraries.

Table 1 shows questions per category recorded in all 14 libraries in percentage

(number). The results show that the largest number of questions was related to

the physical collections and revolved around what is found in the library

room.

Table 1

Percentage (Number) of Questions per Category

|

|

Collection and Access |

Counselling/ Guidance |

Citing and Referencing |

Loan |

Practical |

IT |

Other |

Total |

|

November 2017 |

18% |

5% |

1% |

41% |

23% |

9% |

3% |

100% |

|

(479) |

(125) |

(33) |

(1094) |

(600) |

(226) |

(80) |

(2637) |

|

|

February 2018 |

17% |

8% |

2% |

50% |

13% |

6% |

4% |

100% |

|

(370) |

(180) |

(35) |

(1074) |

(274) |

(134) |

(85) |

(2152) |

|

|

April 2018 |

19% |

11% |

4% |

45% |

13% |

6% |

3% |

100% |

|

(445) |

(269) |

(89) |

(1055) |

(296) |

(138) |

(69) |

(2361) |

|

|

September 2018 |

21% |

7% |

1% |

40% |

17% |

10% |

5% |

100% |

|

(532) |

(189) |

(25) |

(1003) |

(421) |

(241) |

(122) |

(2533) |

|

|

Total |

19% |

8% |

2% |

44% |

16% |

8% |

4% |

100% |

|

(1826) |

(763) |

(182) |

(4226) |

(1591) |

(739) |

(356) |

(9683) |

Divided into 14 libraries, a total of 9,683 questions

corresponds to 35 questions per library per day.

The distribution of questions in the different

categories was quite stable throughout the four weeks. Loan was the category

with the most questions, with 44% on average for the four weeks. This was

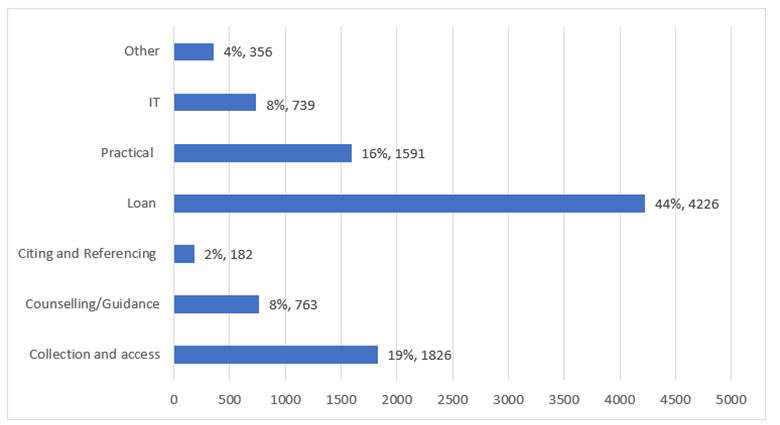

followed by collection and access with 19%. Figure 1 shows the distribution of

questions in the categories for all four weeks in total.

The two categories with the greatest variation were

Counselling/Guidance, with 5% in the recording week in November 2017 and 11% in

April 2018. There were also more questions in the Practical category in

the two recording weeks in the fall (23% and 17%) than in the other two weeks

(13% both).

We found no large variation in the type of questions

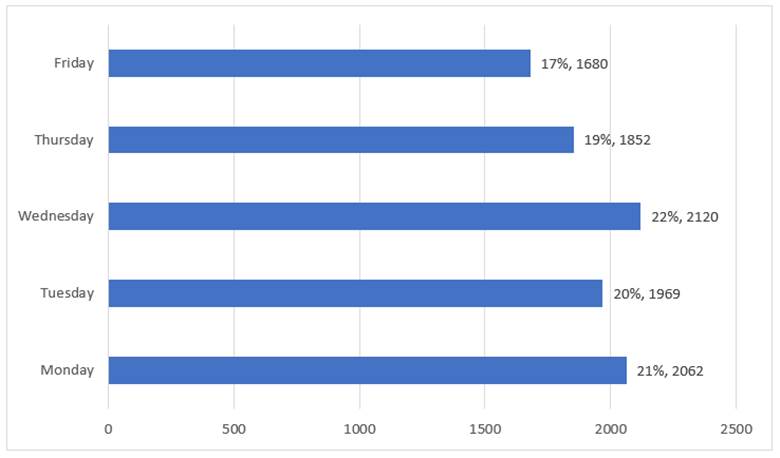

on the different days of the week. Figure 2 shows the distribution of questions

according to days for all four weeks in total. The average shows slightly fewer

questions on Fridays (17%) and slightly more questions on Wednesdays (22%) than

on the other days.

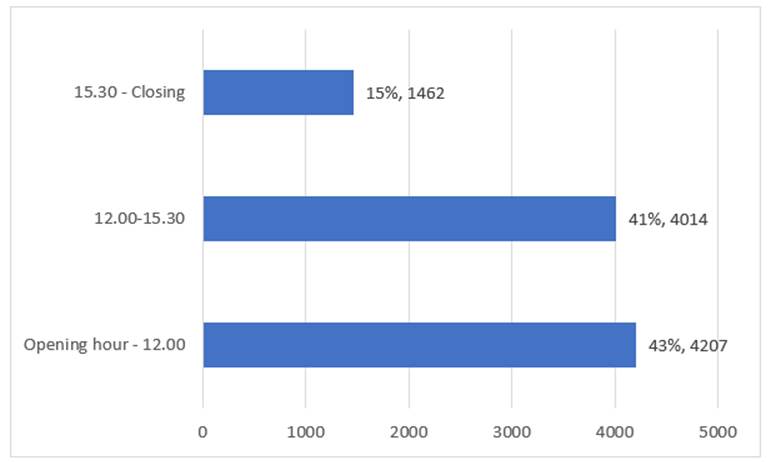

In this study, we recorded questions in three

different time periods each day and looked at how the questions were spread

throughout the day. We did not find any large variation in the different time

periods. The pattern showed a comparatively even number of questions between

opening hours and 3:30p.m. and less from 3:30p.m. until closing. Figure 3 shows

the distribution of questions in the different time periods.

To

maintain anonymity, we were prevented from breaking down results by library.

However, we did not find a clear connection

between the number of questions and the size of the branch libraries. Some of

the small- and medium-sized branch libraries had a relatively larger number of

questions than the biggest libraries. Measured in questions per library

employee, it was also not the largest libraries that received the most

questions. To give one example, one of the smallest branch libraries that cover

health and social sciences had 439 questions per employee, while one of the

largest libraries had 89. We will discuss possible explanations for this in the

discussion section.

Figure 1

Questions per category in total for all four weeks.

Figure 2

Questions per day of the week.

Figure 3

The spread of questions throughout the day.

Discussion

Our study shows that students ask about a lot more

than just borrowing staples at the library desk. In fact, 44% of the questions

were about loan services and document delivery; 19% were about physical and

electronic collections and how to access to them; 16% were about practical

things, such as opening hours, lost and found items, and the location of the

group study rooms; 7% of the questions were about IT. Finally, the results show

that 8% of the questions from the four weeks of counting were counselling and

guidance questions and 2% were about literature lists, reference management,

and reference management tools.

The recording of students´ questions was conducted by

the desk staff in all 14 branch libraries at the university. In a previous

study (Kesselmann & Watstein, 1987), it turned out that as many as 45% of questions were

categorized incorrectly. We have no reason to believe that the percentage is

that high in our study, but there are of course several possible sources of

error: some may have misunderstood the content of the categories, forgotten to

record questions, recorded inaccurate or

double-recorded questions and so on. The fact that so many different staff

members were involved in the recording is another possible source of error. We

must, therefore, assume that there may be some errors in our data. Since both

the recording form itself and the recording process were thoroughly quality

checked before we started the recording, nothing indicates that major

systematic errors were made.

It is interesting to compare our study with other

similar ones (Le Mire et al., 2016; Lenkart & Yu,

2017; Ryan, 2008). Admittedly, we cannot compare the studies directly, both

because the categorization of types of questions varies somewhat, plus some of

the studies, unlike ours, included email and chat transactions. Nevertheless,

we can still see some similarities. Our findings show that 19% of the questions

were in the collection and access category, while the corresponding percentage

in Le Mire et al.’s study (2016) was 15% (category named Locate materials). In Lenkart and Yu´s study (2017), 6.3% of the questions were

inquiries for research assistance. The corresponding percentage in our study

was 8%.

These findings are about similarities, but we also

find differences. Lenkart and Yu (2017) found that

22.8% were questions about library materials, while our results showed 44%.

Ryan (2008) found that 12.4% of the questions were about technology (Excel,

logins, passwords, and networks) and in our study the corresponding number was

8%.

The comparison with international studies is

interesting, but it is also worth comparing our findings with other Norwegian

studies due to a common cultural and organizational context. Several university

libraries in Norway are currently running projects about the service desk,

including a mapping of questions. Unfortunately, little has been published so

far. In an unpublished study from a project conducted in 2016, researchers at

Oslo Metropolitan University found that 53% of the questions fell into the categories

of Procedure and Collection. This corresponds roughly to the two categories in

our study, Collection and Access and Loans, for which the percentage is 63%.

There is also a similarity between these two studies when it comes to the

category Counselling/Guidance questions in our study and the similar category

Subject search in the unpublished study: 8% and 12.4%, respectively. So how can

one interpret this similarity in results and the fact that the percentage of

Counselling/Guidance questions seems to be relatively low? We do not have

previous data on the number of Counselling/Guidance questions in

Norwegian academic libraries. However, from Norwegian official government

statistics, we do know that in recent years the volume of courses and

individual guidance sessions by appointment has increased (Statistisk

sentralbyrå, 2019a). Could it be that a great deal of

the Counselling/Guidance questions are channelled through these services

instead of the library desks? The question is whether this practice is optimal

or whether one should, to a greater extent, use the desk as an educational tool

in such a way that students are encouraged to also use the desk for counselling

and guidance questions. Maybe that would be a more resource-efficient way to

utilize the library desk service. However, it is important to conduct more

studies on these issues.

The two categories with the greatest variation between the recording weeks were

Counselling/Guidance and Practical. The Counselling/Guidance category makes

sense because the students submit their bachelor’s and master’s theses in the

spring and therefore will have more questions on this topic. There were also

some more practical questions in the two recording weeks in the fall (September

and November) than in the other two weeks. The reason for this is somewhat

unclear but could be connected to the fact that new students usually have more

practical questions in connection with the start of the school year.

We did not find any obvious connection between the size of the branch library

and the number of questions asked at the desk. It was not the case that the

larger the library, the more questions were asked. In fact, at one of the

smallest branch libraries, 439 questions per employee were asked, while at one

of the largest, there were 89 questions. In the study, we have not investigated

the reasons for this, but we have some suggestions. We ask ourselves if a

higher share of printed material generates more questions at the service desks?

Although the proportion of electronic literature is increasing, printed

literature is still widely used in Norwegian university libraries (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2019b).

Moreover, our own experience of working for several years in libraries within

different subject areas, have shown us that there are differences in library

use between disciplines. We have not found any Norwegian research to back this,

but we believe that the findings in our study reflect that assertion. Another

reason may be that some libraries have a stronger position among staff and

students than others do and therefore are used more. This could be due to a

greater proximity in smaller professional environments, making it easier to

contact the library desk.

Our

recording form, with few parameters and the recording process itself, worked

well for this study, particularly considering that so many employees were

involved in the data gathering. The subject categories were general enough to

make the question recording easy and at the same time they were well suited for

our analysis. The recording method can be recommended for other libraries,

especially big multi-branch libraries.

Even if the recording form was simple,

time-of-semester and time-of-day activity was admittedly taken care of.

However, unlike other studies, we did not record subcategories (Ryan, 2008) or

time use (Gerlich & Berard,

2007). Our findings showed a low percentage of Counselling/Guidance questions,

8%, but these questions are extra time-consuming. A possible follow-up study

could use a recording system that includes the time aspect, for instance the

READ scale (Gerlich & Berard,

2007). Other variables that can provide richer data material and can be

considered in further research are questions in new areas, like open-access

publishing, maker spaces, and so on (LeMire et al.,

2016). Further research may also include user groups other than students and

other communication channels besides the personal meeting at the desk.

Another interesting point, which we did not address in

our study, is that simple, practical questions can lead to other, more complex

ones. Once the dialogue between staff and student has been established in the

personal meeting at the desk, it may be easier for the student to ask even more

questions and more complex and time-consuming ones. One short question may

reveal a deeper need for information. In our experience, this happens at our

university library, but we do not know how often and how the mechanism works.

On the other hand, we also did not investigate what kind of follow-up questions

the library staff asked students who approached the desk. The lack of these

perspectives is a limitation in our study but are well suited for subsequent

studies. Even though our

study aimed to broaden the knowledge about one library, our own, this is a

limitation and later studies should include other libraries as well.

What

significance does our study have for further practice? The

results are still discussed at the University Library, but so far there

have been no changes in the desk staffing. Recording of questions asked at the desks will continue after the

project period and will be carried out twice a year in the future. Most

important is that awareness

of the various aspects of desk service seem to have increased. This awareness

had led to more discussions about desk service issues in both formal and

informal meetings. Also, a forum has been established for presentation and

discussion about desk related issues, like dissemination of the library’s

electronic collections, access to special collections, and so on.

The

purpose is to develop competence to guide users. Our study will, in combination with other research results and a longer

time of recording, provide the library with a better basis for further

development of the desk service.

Conclusion

In

this study, we examined students’ use of the service desks in all branch

libraries at a large university.

During four different weeks throughout the academic year, we mapped desk

activity. We sorted the questions asked in the personal meetings at the desk

into predefined subject categories. Most of the questions were about loan

services, document delivery, and use of and access to physical and electronic

collections (63%). In total, there was little variation between the categories

from week to week, but we did find some differences. For example, there were

more Counselling/Guidance questions in the assignment and exam period in the

spring and more questions of a practical nature in the two autumn weeks.

Results indicated that there was no obvious

relationship between the branch library size and the number of questions asked.

It seems that some study programs have a greater need for library services than

others. This is one of the factors to consider when dimensioning and organizing

the desk service in the future.

Through this study, we have gained more knowledge

about the purpose of students’ use of the service desk. These findings

from a large Norwegian multi-branch library is a unique contribution to the

body of data that already exists internationally about the topic. In our study,

we have developed a recording methodology, which

we think is well suited for other large, multi-branch libraries. If more

researchers use the same recording methodology, it will make it easier to

compare findings between libraries and between countries in the future.

Our

newly gained knowledge has been and will continue to be used for further

development of the desk service at our university. Interesting themes for

subsequent studies could be to investigate the consequences of different types

of follow-up approaches for the fulfilment of student information needs. Other ways to

broaden our knowledge could be to include other user groups as well. Finally,

other communication channels other than the personal meeting at the desk would

be of interest for future researchers.

References

Gerlich, B. K., & Berard, G. L. (2007). Introducing the READ scale: Qualitative statistics for academic

reference services. Georgia Library Quarterly, 43(4), 7-13. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=glq

Henry, D. B., & Neville, T. M. (2008). Testing classification systems for reference

questions. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 47(4),

364-373.

https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.47n4.364

Katz, B. (2002). Introduction to reference work,

Vol. 2: Reference services and reference processes (8th ed.).

McGraw-Hill.

Kesselmann, M. & Watstein, S. (1987). The Measurement of reference and

information services. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 13(1),

24–30.

LeMire, S.,

Rutledge, L., & Brunvand, A. (2016). Taking a fresh look: Reviewing and

classifying reference statistics for data-driven decision making. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 55(3), 230–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/rusq.55n3.230

Lenkart, J., & Yu, J. (2017). Specialized reference services at Illinois:

Reference transactional analysis and its implications for service providers and

administrators. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 56(4),

268–276. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.56.4.268

Radford, M. L., & Connaway,

L. S. (2013). Not dead yet! A longitudinal study of query type and ready

reference accuracy in live chat and IM reference. Library & Information

Science Research, 35(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.08.001

Ryan, S. M. (2008). Reference transactions analysis:

The cost-effectiveness of staffing a traditional academic reference desk. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(5), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.06.002

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019a). 10872: Opplæring i

bibliotekbruk og primærmålgruppe i fag-og forskingsbibliotek, etter

bibliotektype 2013 – 2019 [Statistikk]. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/10872/

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019b). 10870: 10870:

Bestand og tilvekst ved i fag- og forskningsbibliotek, etter

statistikkvariabel, bibliotektype og år [Statistikk]. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/10870/

Warner, D. G.

(2001). A new classification for reference statistics. Reference

& User Services Quarterly, 41(1), 51–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41240900

Appendix

The TREFF-project, registration of questions at the library desk, week

xx (Monday [date] – Friday [date] [year])

Library: Date:

Use one registration form per day. Register each question in the

right category (there may

be several questions per inquiry).

One tallymark per question. REGISTRATE

QUESTIONS ONLY FROM STUDENTS. Do not register questions asked via email or

telephone.

|

Categories |

Opening Hours - 12.00 |

12.00 - 15.30 |

15.30 – Closing Time |

|

Collection and Access (Digital and printed

collections). E.g.: do you have <title>, Where do I

find…, How do I get access… |

|

|

|

|

Counselling/Guidance (Reference questions) E.g.: do you have material about…, is this a

scientific journal article, how to search, where to search… |

|

|

|

|

Citing and Referencing E.g.: how to cite, make bibliographies, use

reference tools (not technical questions about installing programs = IT-questions) |

|

|

|

|

Loan (loan, library card, request) E.g.: loan/return, help with self-check,

questions about due date, resource sharing, collecting requested material,

claims, return receipt, logging into databases |

|

|

|

|

Practical questions (rooms/buildings/equipment) E.g.: where to find study rooms, cafes, auditoriums …, complaint

about bad air, what are the opening hours, where to deliver lost property,

borrow a stapler etc., where is the printer |

|

|

|

|

IT-questions E.g.: laptop printing, printing problems,

internet access, questions about installation and use of software |

|

|

|

|

Other questions (register a tallymark and

write down the question). E.g.:

administrative matters |

|

|

|