Research Article

Coping with Impostor Feelings: Evidence Based

Recommendations from a Mixed Methods Study

Jill Barr-Walker

Clinical Librarian

Zuckerberg San Francisco

General Hospital Library

University of California,

San Francisco

San Francisco, California,

United States of America

Email: [email protected]

Debra A. Werner

Director of Library Research

in Medical Education

John Crerar Library

University of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Liz Kellermeyer

Biomedical Research

Librarian

Library & Knowledge

Services

National Jewish Health

Denver, Colorado, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Michelle B. Bass

Manager, Research and Instruction

Countway Library of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Boston, Massachusetts,

United States of America

Email: [email protected]

Received: 8 Jan. 2020 Accepted: 11 Apr. 2020

![]() 2020 Barr-Walker, Werner, Kellermeyer, and Bass. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Barr-Walker, Werner, Kellermeyer, and Bass. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Barr-Walker, J., Bass, M. B., Werner, D. A., &

Kellermeyer, L. (2019). Coping with impostor feelings: Evidence-based

recommendations from a mixed methods study (V2) [Survey instrument, data,

codebooks]. UC San Francisco. https://doi.org/10.7272/Q65T3HP6. The survey

instrument is available in appendix 1. The de-identified data and codebook as

well as qualitative codebooks are available in data appendices 2 and 3.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29706

Abstract

Objective – The negative effects

of impostor phenomenon, also called impostor syndrome, include burnout and

decreased job satisfaction and have led to an increased interest in addressing

this issue in libraries in recent years. While previous research has shown that

many librarians experience impostor phenomenon, the experience of coping with

these feelings has not been widely studied. The aim of our study was to

understand how health sciences librarians cope with impostor phenomenon in the

workplace.

Methods – We conducted a census of 2125 Medical Library Association members

between October and December 2017. An online survey featuring the Harvey

Impostor Phenomenon scale and open-ended questions about coping strategies to

address impostor phenomenon at work was administered to all eligible

participants. We used thematic analysis to explore strategies for addressing

impostor phenomenon and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine

relationships between impostor phenomenon scores and coping strategies.

Results – Among 703 survey respondents, 460 participants completed the

qualitative portion of the survey (65%). We found that external coping

strategies that drew on the help of another person or resource, such as

education, support from colleagues, and mentorship, were associated with lower

impostor scores and more often rated by participants as effective, while

internal strategies like reflection, mindfulness, and recording praise were

associated with less effectiveness and a greater likelihood of impostor feelings.

Most respondents reported their strategies to be effective, and the use of any

strategy appeared to be more effective than not using one at all.

Conclusions – This study provides evidence based recommendations for

librarians, library leaders, and professional organizations to raise awareness

about impostor phenomenon and support our colleagues experiencing these

feelings. We

attempt to situate our recommendations within the context of potential

barriers, such as white supremacy culture, the resilience narrative, and the

lack of open communication in library organizations.

Introduction

Impostor phenomenon, also known as impostor syndrome

or impostor experience, is defined as an internal feeling of not deserving

personal success that has been rightfully achieved (Clark et al., 2014).

Individuals experiencing impostor

phenomenon may believe that they have fooled others

into overestimating their own abilities; attribute personal success to factors

other than their own ability or intelligence, such as luck, extra work,

charisma, or misjudgment; and fear exposure as an impostor (Clark et al.,

2014). Existing research has shown that up to 70% of the population has

experienced impostor phenomenon (Harvey & Katz, 1985), and many people

suffer from its associated adverse effects such as anxiety, depression, lack of

confidence, decreased job satisfaction and performance, and inability to

achieve in the face of self-imposed unattainable goals, which can lead to

burnout (Parkman, 2016).

The current study is part of a larger research project

that hypothesized higher rates of impostor phenomenon among health sciences

librarians compared to college and research librarians, primarily because of

the lack of educational background health sciences librarians hold in their

subject areas. This effect was not found, suggesting that the current study's findings

around coping strategies are broadly applicable across the academic librarian

community.

While anecdotal evidence and a growing body of research have shown that

impostor phenomenon in librarianship exists, no studies have examined how

librarians cope with this phenomenon. Our study attempts to provide an evidence

base for recommendations to address impostor phenomenon among librarians.

Literature Review

Impostor phenomenon has been studied extensively in academia, with two

comprehensive literature reviews focusing on the existing research in this

field (Parkman, 2016; Parkman & Beard, 2008). Many studies have documented

the prevalence of impostor phenomenon among faculty, students, and staff, with

some noting that the academic environment of “scholarly isolation, aggressive

competitiveness, disciplinary nationalism, a lack of mentoring and the

valuation of product over process” (McDevitt, 2006, p. 1) may cultivate

impostor feelings. Race and gender, previously thought to be unrelated to the

experience of impostor phenomenon, have recently shown associations with

impostor scores in academic populations, including women graduate students

(Collett et al., 2013; Oriel et al., 2004) and Black undergraduate students

(Bernard et al., 2018; Cokley et al., 2017). Within academic libraries, two

studies have shown that one in eight librarians have experienced impostor

phenomenon, with younger and newer librarians demonstrating higher impostor

scores than their older and more experienced colleagues (Barr-Walker et al.,

2019; Clark et al., 2014).

Although countless studies have measured the prevalence of impostor

phenomenon using two validated measurements (Clance & Imes, 1978; Harvey

& Katz, 1985), few studies have examined the ways in which people with

impostor phenomenon successfully cope with these feelings. Two studies

discovered a range of coping strategies used by faculty, including seeking

support from colleagues, family, and friends; correcting cognitive distortions

about the meaning of success and validating successes; and using avoidant

behaviors like substance use, ignoring impostor feelings, and working harder

(Hutchins & Rainbolt, 2017; Rakestraw, 2017). Mentor relationships were

consistently reported as a successful strategy for addressing impostor phenomenon,

with mentors encouraging participants to own their accomplishments, reassuring

them about the normalcy of impostor feelings, modeling positive behaviors like

avoiding unrealistic comparison with others, and providing emotional and

practical support, including ideas and advice about their work (Hutchins &

Rainbolt, 2017). Importantly, while all strategies lessened impostor feelings,

this lessening was reported as a temporary effect overall.

Despite the lack of research on the use of coping strategies, most of

the literature on impostor phenomenon recommends similar strategies at the

individual level (e.g., recording accomplishments, self-evaluation,

collaborating with colleagues), the managerial level (e.g., giving praise to

direct reports, accepting mistakes), and the organizational level (e.g.,

creating mentoring programs) (De Vries, 2005; Parkman, 2016; Rakestraw, 2017).

Within academia, programs for faculty, staff, and students have been developed

to acknowledge and address impostor phenomenon, including awareness workshops

at faculty orientations, mentoring and peer group programs, regular discussions

for first-year employees, and the implementation of structured feedback systems

(Parkman, 2016). Recommendations in the literature for supervisors include

giving positive, documented feedback, facilitating a written record of

accomplishments for employees, discussing clearly what success and excellence

in a particular position might look like, modeling work-life balance while

eschewing expectations of perfection, and being aware of the signs of impostor

phenomenon in order to prevent and address it (De Vries, 2005; Rakestraw,

2017).

Efforts to raise awareness about impostor phenomenon within academic

librarianship have increased in the last five years, with American Library

Association-sponsored webinars (Conner-Gaten, Van Ness, & Tate-Louie, 2018;

Puckett, 2018), the appearance of regular workshops at conferences like the New

Librarian Symposium and the Association of College and Research Libraries

(ACRL) conference, and a proliferation of published articles on the topic

(Agostino & Cassidy, 2019; Lacey

& Parlette-Stewart, 2017; Murphy, 2016; Rakestraw, 2017; Sobotka, 2014).

Despite this increased interest, no evidence yet exists to support the range of

recommendations that are widely suggested to address impostor phenomenon.

Aims

The aim of this study was to understand how health

sciences librarians cope with impostor phenomenon. Our research questions

include the following: How are librarians experiencing impostor phenomenon at

work? What types of coping strategies do librarians use to address these

impostor feelings? How effective are current coping strategies at addressing

impostor phenomenon? By answering these questions, we seek to provide evidence

based solutions for addressing the experience of impostor phenomenon among

librarians.

Methods

We developed an online, anonymous survey using REDCap,

a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research

studies. Our survey contained the 14-statement Harvey Impostor Phenomenon

scale, seven demographic questions, and two open-ended questions: "Do you

use any strategies to address feelings of inadequacy at work?" and

"If applicable, how effective are these strategies in addressing those

feelings of inadequacy?" (see

appendix 1 referenced in Data Availability).

The development of our survey instrument has been described in detail

elsewhere (Barr-Walker et al., 2019). Briefly, the Harvey Impostor Phenomenon

scale, developed in 1981, is a validated tool widely used to measure impostor

phenomenon (Harvey & Katz, 1985). The Harvey scale contains 14 statements

that respondents score on a scale of 1 to 7, representing "Not at all

true" to "Very true"; some statements are reverse scored. For

example, a statement like "In general, people tend to believe I am more

competent than I really am" is scored as 1 for "Not at all true"

and 7 for "Very true," while a statement like "I feel I deserve

whatever honors, recognition, or praise I receive" is reverse scored.

Overall scores can range from 0 to 84, with higher scores corresponding to

higher instance of impostor phenomenon. Scores of 42 and higher "may

indicate possible troubles due to impostor feelings, and scores in the upper

range suggest significant anxiety" (Harvey & Katz, 1985).

Univariate analysis and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s

post-hoc test were completed in Stata, a statistical analysis software, by one

author (Author 1). For qualitative analysis, two authors (Author 1 & Author

2) used thematic analysis (Silverman, 2003; Wolcott, 2001) to create 14 codes

from the responses to the open-ended survey questions using Google Sheets.

Participant responses were reviewed independently by both authors who then

shared their ideas about emerging themes and came to consensus on codes; the

two authors then independently assigned thematic codes to each response.

Inter-rater reliability was conducted after this step, with both authors

checking each response and resolving any discrepancies between code assignments

via deliberation until resolution. Study data and corresponding codebooks are

available in appendices 2 and 3 noted in Data Availability.

All 2,125 eligible members of the Medical Library

Association (excluding students, unemployed members, and members located

outside the United States) were emailed an invitation to complete the online

survey in October 2017, with two reminders sent over the next two months; the

survey closed for responses on December 31, 2017. This study was approved as

exempt research by the University of California, San Francisco IRB (study

#17-22873).

Results

Respondents

Of those surveyed, 703 respondents completed the survey (33% response

rate), and 460 (65% of those who completed the survey) provided information for

the two open-ended questions about strategies used to address feelings of

inadequacy at work and the effectiveness of those strategies. Quantitative

analysis of the study results has been reported elsewhere (Barr-Walker et al.,

2019); for the purposes of this paper, we will report only on the 460

respondents who completed the open-ended questions.

Most of the 460 respondents identified as women (85%)

and White (84%), worked in an academic library (58%), had an MLS degree (98%),

did not have educational training in a health sciences field (62%), and had 11

or more years of experience working in libraries (55%). Age varied among

respondents: the majority were between 36-50 (37%) or over 51 (44%), with a

smaller percentage under 36 (19%). While total impostor phenomenon scores

ranged from 5-70 (out of a possible 84), the average impostor score was 28.69,

with 15% of respondents scoring 42 or above, indicating an experience of

impostor phenomenon (Harvey & Katz, 1985). These results reflected the

overall trends among the 703 participants of the survey (Barr-Walker et al.,

2019), indicating that the 460 respondents examined in the current study were

representative of this larger population.

Strategy Types

We identified 22 types of coping strategy themes, listed in Table 1 (see

end of the article). The most frequently reported strategy was education (n =

173), followed by support from colleagues (n = 133), reflection (n =

87), perseverance (n = 54), and mindfulness (n = 47). About half

of respondents (55%) reported a single strategy, while the rest described

multiple strategies: there were no significant differences in impostor scores

at the p < 0.05 level between those who selected one or multiple

strategies [F(1,458) = 1.92, p = 0.17].

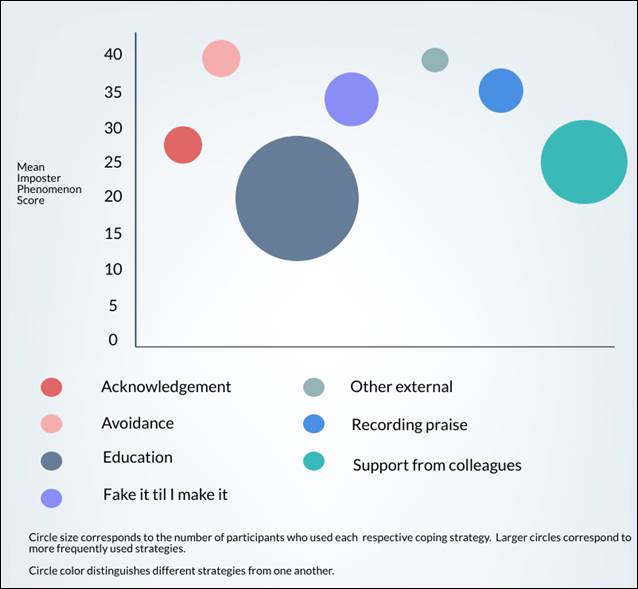

The strategies that corresponded to the highest mean impostor phenomenon

scores, indicating greater likelihood of impostor feelings), were avoidance

(38.59), other external (37.13), recording praise (34.5), and fake it ’til I

make it (34.1), with the lowest mean impostor phenomenon scores for support

from colleagues (28.95), acknowledgement (27.19), and education (25.95) (Figure

1).

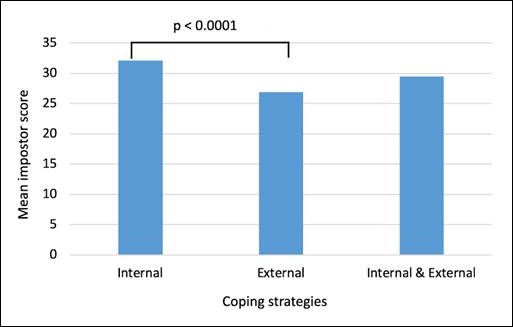

We categorized each strategy as “internal” or “external” based on

whether or not the respondent relied on another person or resource as part of

the strategy. For example, internal strategies included reflection,

mindfulness, and perseverance, all of which can be done by one individual

without the assistance of another, while external strategies include education,

mentorship, and support from colleagues. Respondents were split between

reporting strategies categorized as internal (n = 176), external (n =

172), or both (n = 111). Many respondents included multiple internal or

external strategies in their responses, but only those who included at least

one strategy of each type were counted as having used both. Using one-way ANOVA

with Tukey’s post hoc test, significant differences at the p < 0.0001

level were observed in impostor scores between two groups, with those reporting

only internal strategies having higher mean scores than those who reported only

external strategies [F(2, 457) = 9.24, p

= 0.0001]. Although mean scores were lower for those that used both internal

and external strategies than those using internal strategies only, this was not

a significant effect (Figure 2). There were no significant differences in the

use of external versus internal strategies between demographic groups such as

age, years of experience, race, gender, or type of library, with usage

remaining consistent between groups.

Figure 1

Summary of the strategies with the highest and lowest impostor

score means.

Figure 2

Comparison of impostor scores by type of strategy.

Strategy Effectiveness

Most participants rated their strategies favorably, with 74% of

participants reporting that their strategies were effective (n = 320, M

= 26.81, SD = 10.20). Using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test,

we found that the mean impostor scores for participants who reported that their

strategies were somewhat effective (n = 84, M = 38.25, SD =

9.59) or not effective (n = 21, M = 41.33, SD = 12.20) were

significantly higher than those who reported effective strategies [F(3, 428) = 38.35, p = 0.0001], showing that self-reported effectiveness corresponded

to lower impostor scores. The most frequently reported ineffective strategies

were avoidance, perseverance, and reflection, all internal strategies. The most frequently reported effective

strategies represented a mix of external and internal strategies: education,

support from colleagues, reflection, mindfulness, and perseverance.

Examples of Strategies

Reflection, an internal strategy, was an individual

process focused on reviewing what one has accomplished in order to reach the

current position in their career. Examples focused on both general

accomplishments, “I remind myself of what I’ve done in the past, and the things

I’ve learned, and the fact that I can learn more,” and achievements related to

their job roles:

“I have my

school diplomas on my office wall -- both my undergrad… and grad, which was a

master's degree; the purpose isn't to impress or intimidate other people --

they are there to remind *me* that I do belong legitimately in my office.

Sometimes I wonder if that's why other people have theirs on their own walls,

too.”

Education was a commonly referenced external coping

strategy that involved engagement with resources beyond an individual’s own

knowledge. One participant stated, “I try to participate in a lot of

professional development, especially free professional development

opportunities: MOOCs for example.” Another participant gathered ideas for

educational opportunities by “attending professional development sessions;

reading colleagues’ resumes and LinkedIn accounts to learn about ways to

improve my own.”

Effectiveness of Strategies

Out of the 74% of participants that rated their

strategies as effective, the most frequently reported were education and

support from colleagues, external strategies that were associated with lower

impostor scores. While responses around formal education like CE courses,

advanced degrees, and professional conference participation were common,

participants also found informal educational opportunities and support from

colleagues to be effective:

“I take

additional classes or read articles and books to improve areas that need work.

These strategies help, but implementing them and seeing improvements helps

improve feelings more than just completing a class or readings.”

“Ask questions,

seek help, go to experts, seek feedback. It broadens my knowledge and makes me

more confident.”

Receiving support from colleagues and mentors, inside

and outside their own libraries, was often mentioned as an effective strategy:

“I usually find

a colleague that is at the same stage or slightly further along than me to

bounce ideas off of. I also try to reach out to mentors who may not necessarily

be in my field, to compare my ideas with them. [This is] usually very

successful, I think often I underestimate my thought process, and they often

assure me that I am on the right path.”

“I have several trusted colleagues at my place

of work, and several from previous employment that I discuss any uncertainties

I am feeling to work through my impostor syndrome. [This is] highly effective.

Sometimes bouncing ideas off of another person is all I need, and occasionally

reassurance that I'm not inept or that I am the right person for the job is

necessary. Mostly it just helps boost my confidence and strengthen my ideas.”

“I try to talk to colleagues in other medical

libraries who can understand my feelings. [This is] very effective! My fellow

librarians are so helpful and empathetic - they make me feel that I am not

alone."

Although internal strategies alone were associated with higher impostor

scores, some individuals reported their use of these strategies to be

effective. Many responses combined internal and external strategies, such as

the following example which includes reflection, recording praise, and support

from colleagues:

“I list all of

the projects that I am currently working on, and all of the projects that I

have completed, whether I did a great job or a not-so-good job. I sometimes

also think about how I could be doing a worse job and imagine what that would

look like. I then think about what I could be doing better and list small steps

for improvement. Talking to peers that you are close with also helps. You

recognize that you are not alone and that you may be doing better than you

thought. The list helped me to recognize the hard work that I've put in and

does help me feel like I'm doing enough, or more than enough, in my position.

Imagining what doing a worse job would look like helps a great deal in

addressing feelings of inadequacy. Talking to peers helps significantly.”

Individual Coping Strategies

The two measurements used in our study, impostor phenomenon scores and

self-reported effectiveness, provide evidence of the association between

external strategies, lower impostor scores, and greater self-reported

effectiveness. However, variations exist among individual strategies:

perseverance, for example, was one of the most frequently reported ineffective

strategies but was associated with a lower impostor score than mentorship, a

strategy often self-reported as effective. How can we explain this? Looking

closer at this particular strategy reveals that 72% of respondents that

reported perseverance also used at least one additional strategy; because

almost half of respondents used more than one strategy, it is difficult to

separate the effects of any individual strategy from another. What seems clear

from our aggregate data is the fact that using any strategy to deal with

feelings of impostor phenomenon seems to be helpful, both in terms of

self-reported effectiveness and impostor phenomenon score. Within the choice of

strategy type, our evidence points to the use of external strategies.

Education was the most commonly reported external coping strategy, was

self-reported as effective, and was associated with the lowest mean imposter

score of all reported coping strategies. We did not distinguish between formal

and informal education in our analysis; therefore, educational strategies could

include anything from taking for-credit courses to reading articles.

Recommending educational strategies to combat impostor phenomenon, then, seems

straightforward, and for those who are able to participate in educational

activities, it is our highest recommendation to counter impostor feelings.

However, we must also acknowledge the potential barriers to utilizing this

strategy: lack of resources to pay for courses, webinars, or paywalled

articles; uncertainty, particularly for newer librarians, about whether

engaging in educational activities while at work is acceptable; and lack of

time to engage in these activities. Suggestions for organizations and leaders

to address these barriers are discussed in the next section.

Another self-reported effective external strategy was support from

colleagues. This strategy may work well when one has already established a

network of trusted colleagues, but in some workplace environments, this is not

a feasible option. Solo librarians, for example, must look for support outside

of their own libraries where they may lose the shared experience that support

from an institutional colleague often provides. Librarians new to an institution

might not know others well enough or be unsure when to ask for support.

Additionally, while many respondents described trusted colleagues, others

described environments where they lacked support or encountered toxic

colleagues. For librarians who are able to develop networks of trusted

colleagues, the ability to share feelings around impostor phenomenon can help

confirm that these feelings are shared by successful people; many respondents

in our survey described not feeling so alone after discussions with colleagues

about these issues. Support from colleagues, therefore, can serve as an

individual coping strategy and a way to raise awareness about impostor

phenomenon within our field.

One self-reported effective internal coping strategy

was acknowledgement: stating and accepting one’s lack of knowledge on a given

topic. This strategy, while not reported nearly as frequently as education or

support from colleagues, reflected the second lowest mean impostor score,

following education. Overall, internal strategies like mindfulness, fake it

’til I make it, and avoidance were associated with higher mean imposter scores

than external strategies, but acknowledging a gap in knowledge is a necessary

step before taking action, like seeking additional education or support from

colleagues; in this context, its effectiveness makes sense.

Some differences observed in internal and external scores and

self-reported effectiveness may be explained by the fact that several internal

strategies match impostor phenomenon indicators. For example, overpreparing,

fake it ’til I make it, perseverance, and avoidance are coping strategies that

also describe the characteristics of those with impostor feelings. It is not

surprising that some of these internal strategies, including avoidance and

perseverance, were self-reported as ineffective.

Less obvious is why the strategy of reflection was

also described as not effective and associated with higher impostor scores. One

possible explanation is that self-reflection, if using the warped mirror of

impostor phenomenon, can reinforce negative thoughts and perceptions.

Impostorism has been described as “an inability to accurately self-assess with

regard to performance” (Parkman, 2016). When reflecting on performance, those

who experience impostor feelings will likely undervalue their strengths and

achievements and overemphasize their mistakes and failures. Reflection and

recording praise (i.e., looking back at the things you have accomplished and

praise you have received) are commonly recommended techniques to combat

impostor phenomenon (De Vries, 2005; Hutchins & Rainbolt, 2017; Lacey &

Parlette-Stewart, 2017). However, these internal strategies were associated

with higher mean impostor scores in our study, indicating that if one is to use

them, they should be combined with external strategies to increase their

likelihood of effectiveness.

Addressing Impostor Phenomenon Through Organizational Culture

Change

Beyond individual coping strategies, another method of addressing

impostor phenomenon may come at the leadership level. Several studies suggest a

potential association between impostor feelings and job roles with a lack of

clarity in their scope (Lacey & Parlette-Stewart, 2017; Parkman, 2016). In

librarian positions where individuals are often responsible for a broad variety

of tasks, performance targets can be vague and may lead to uncertainty about

what success in one’s job looks like. As our findings have shown, support from

colleagues and mentorship are associated with lower impostor scores: improving

communication with librarians, including feedback on job performance, is a

first step toward using these coping techniques. It is important to clarify,

however, that not all feedback leads to decreased uncertainty. A recent study confirmed

that supervisors do not always have an understanding of librarians' work; thus,

feedback received in these cases can be frustrating (Thomas et al., 2017).

Alternative models of feedback such as appreciative inquiry (Rosener et al.,

2019) and two-way feedback systems may help to provide a shared understanding

of librarians' work and allow library leaders to change their expectations

based on librarian feedback. Leaders that prioritize clear, specific feedback

as part of their regular conversations with employees can begin to create a

culture of open communication in which impostor feelings can be acknowledged

and addressed. Leaders in our field have previously advocated for transparency

in communication from leadership (Robertson, 2017) in order to “create a safe

environment for library workers … to talk with one another about their concerns

and needs without fear of reprisal or rejection” (Lew, 2017).

Another opportunity for library leaders who want to create supportive

environments for their staff to address impostor phenomenon is to reject and

disrupt aspects of white supremacy culture in their organizations. White

supremacy culture is the series of characteristics that institutionalize

whiteness and Westernness as normal and superior to other ethnic, racial, and

regional identities and customs (Gray, 2019). Naming whiteness as a culture

helps us question its neutrality and normativity, including how white culture

shapes the norms, beliefs, and ideas of everyone in it (e.g., creating

standards of professionalism for dress code and speech that privilege

whiteness) (Gray, 2019; Hathcock, 2015). Impostor phenomenon can thrive in this

culture because its norms are often not named as such, and librarians whose

work (and, often, personal selves) do not fit these norms may question their

own success and ways of doing things.

Many of the hallmarks of white supremacy culture can reflect the

manifestations of impostor phenomenon in libraries, including perfectionism, a

sense of urgency, individualism, either/or thinking, and quantity over quality,

with several studies linking these two concepts (Berg et al., 2018; Dudău,

2014; Henning et al., 1998; Okun & Jones, 2016; Ross et al., 2001; Thompson

et al., 2000). Although our institutions have historically been shaped by white

supremacy culture, libraries can begin to dismantle these systems by

proactively naming our norms and standards of behavior to reflect the type of

culture that we want to see: one that does not facilitate impostor phenomenon.

To do this, library leaders can recognize that projects often take longer than

expected and create realistic work plans; create environments where it is

expected that everyone will make mistakes and recognize that these mistakes

sometimes lead to positive results; develop a values statement for the library

which expresses the ways in which people want to do their work; evaluate people

based on their ability to delegate to others; and/or make sure that everyone

knows and understands their level of responsibility and authority in the

organization (Okun & Jones, 2016). Library leaders interested in continuing

the anti-racist work of disrupting “the neutrality of whiteness” (Gray, 2019)

in their organizations can look to scholars in our profession who have written

extensively on this topic (Bourg, 2016; Ettarh, 2014; Schlesselman-Tarango,

2017).

In the current study, over 10% of participants described a coping

strategy related to perseverance or not giving up on a task even though you do

not feel fully capable of completion. This feeling of perseverance or

resilience is challenged in the library literature for obscuring structural

issues and shifting responsibilities to library workers to overcome barriers

for success (Berg et al., 2018). Using an example from our study, librarians

may feel that obtaining education in order to relieve feelings of impostor

phenomenon is their responsibility. Framing education as a coping strategy that

individual librarians must seek out ignores structural inequalities that

prevent librarians in low-resource settings or with limited support from their

library administrations from accessing these resources. According to this

theory, resilience encourages library workers “to manage up, to ignore systemic

inequalities, to return to a status quo which too often upholds silence over

difficult change, and reinforces fictions of neutrality” (Berg et al., 2018).

Library leaders can recognize the manifestations of resilience in their

environments and begin to build organizational cultures that reframe resilience.

Resilience can be reimagined in libraries within the context of addressing the

negative effects of impostor phenomenon: library leadership can create

organizations whose values include letting go of unnecessary tasks, embracing

discomfort during new training efforts, and helping staff accept “done” rather

than perfection (Berg et al., 2018).

Moving Forward: Working Together as a Profession

Professional organizations have a role to play in raising awareness

about impostor phenomenon and supporting librarians with educational and

mentorship opportunities. Our study shows that education, support from

colleagues, and mentorship are some of the most effective strategies that

librarians can use to deal with impostor feelings. ACRL, MLA, and others can strengthen

their existing mentorship programs, specifically targeting those who are

younger or new to the profession, groups that displayed higher impostor scores

in our study (Barr-Walker et al., 2019). Professional organizations can also

work together across disciplines (e.g., ACRL, MLA, PLA, SLA) to share expertise

and connect members in different job roles for peer mentoring programs. Local

chapters may be able to play a role in creating a network of supportive

colleagues and mentorship, but these chapters are often underfunded and

understaffed by volunteer librarians. While our professional organizations

currently offer regular educational opportunities including continuing

education classes, webinars, and conferences, we must consider as a profession how

fee-based education creates barriers for librarians in low-resource settings

and how we can support our colleagues without financial resources to pay for

existing educational opportunities. As the results of our study show, external

strategies like education and mentorship are associated with lower impostor

scores; these evidence based approaches should be valued when library leaders

consider budgetary decisions around professional development for staff.

When advocating for mentorship within professional organizations, we

must point out that formal mentorship programs often fail to address the

impacts of white supremacy culture on librarianship, especially around how

librarians of colour must navigate the whiteness of our profession (Brown et

al., 2018). When mentorship programs do not name, identify, or interrogate the

whiteness of our institutions, they are unable to provide a supportive

environment for participants of colour, and may facilitate feelings of impostor

phenomenon, the very thing these programs are designed to disrupt (Brown et

al., 2018; Dancy & Brown, 2011). In addition to supporting and expanding

existing diversity-centered mentorship programs, our organizations can create

supportive environments for librarians of colour in all mentorship programs by

acknowledging the harmful effects of white cultural norms and allowing

participants to express their authentic selves (Brown et al., 2018). Great

strides have been made to create informal and volunteer networks of peer

mentors as a response to the lack of support for librarians of colour in formal

mentoring spaces (Brown et al., 2018); our professional organizations can

recognize this as an opportunity to leverage these networks of experts to

improve existing programs.

Moving forward, future studies can build on our work by examining the

differences in effectiveness between individual coping strategies and how the

use of multiple strategies affects one's experience. Additionally, there is a

lack of research on how librarians' intersectional identities (e.g., race,

gender, socioeconomic status) affect their feelings of inadequacy at work and

how the coping strategies recommended in this study may be experienced

differently based on these identities, rather than as a universal approach.

Although our study did not show differences in impostor scores by race or

gender, the lack of diversity in librarianship combined with the ways in which

dynamics of privilege are enacted in our field may inform interpretations of

these results (Barr-Walker et al., 2019). Future study in this area would allow

us to better understand the associations between impostor phenomenon, how white

supremacy culture is enacted in libraries, and how these intersectional

identities are experienced.

Conclusion

In our census of members of the Medical Library

Association through an online survey, 15% of librarians experienced impostor

phenomenon, and most reported using one or more coping strategies to address

these feelings. External strategies like education, support from colleagues,

and mentorship were associated with self-reported effectiveness and lower

impostor scores. Although our findings showed less evidence for the use of

commonly recommended strategies such as reflection, mindfulness, and recording

praise, it appears that using any strategy at all is more effective than using

none. We encourage librarians and library leaders to develop and utilize

evidence based recommendations to address impostor phenomenon, with careful

consideration given to structural barriers, such as the resilience narrative

and white supremacy culture, within our field.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institute of Research Design in

Librarianship (IRDL), notably Marie Kennedy and Lili Luo, for their support

throughout the research process, particularly in the creation and development

of this project. Special thanks to our colleagues who provided feedback on

drafts of the manuscript: Nisha Mody, Charlie Macquarie, and Eamon Tewell, IRDL

mentor, whose meaningful support throughout this project was unwavering and

essential to its completion.