Research Article

The Information Needs of Canadian Midwives and Their

Evidence Informed Practices: A Canada-Wide Survey

Lindsay Barnes

Research Support Officer

Faculty of Medicine and

Health

The University of Sydney

Sydney, New South Wales,

Australia

Email: [email protected]

Luanne Freund

Associate Professor

School of Information

University of British

Columbia

Vancouver, British Columbia,

Canada

Email: [email protected]

Dean Giustini

University of British

Columbia Biomedical Branch Librarian

VGH Diamond Health Care

Centre

Vancouver, British Columbia,

Canada

Email: [email protected]

Received: 4 Aug. 2019 Accepted: 29 Jan. 2020

![]() 2020 Barnes, Freund, and Giustini. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Barnes, Freund, and Giustini. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29616

Abstract

Objective – The study aim

was to

understand the extent to which Canadian registered midwives have access to and

make use of clinically relevant information for evidence

based midwifery practice.

Methods – A survey instrument was

created consisting of 17 multiple choice, matrix table, and

short answer questions and distributed to 1,690 recipients on the Canadian

Association of Midwives email list in fall 2018. In total, 193 responses were

included in the analysis.

Results – One third of midwives

do not have library

memberships. Midwives reported that limited access to clinically relevant

information is a key challenge in applying information in practice. Midwives

with library memberships reported more frequent use of high-quality information

while midwives without memberships reported more frequent use of websites.

Midwives with advanced degrees (graduate, PhDs) were more likely to be

high-frequency information users and rank themselves higher on evidence based competency scales than their

undergraduate-holding colleagues. Clinical practice guidelines were important

information sources and used frequently by midwives.

Conclusion – Midwives

reported low levels of academic or hospital library

memberships and yet used information frequently.

Clinical practice guidelines support the work of midwives but are

inaccessible to some due to paywalls. Midwives lacked confidence in evidence based practice and reported critical appraisal as

an area for development. Solutions to these problems could be addressed at the

hospital, health authority, provincial, or national association level, or

within midwifery departments at Canadian universities. Hospital and academic

libraries should prioritize the information needs of students and practicing

midwives and identify ways to foster use of library resources through

administrative or educational interventions.

Introduction

Midwives in Canada are autonomous care providers who

provide evidence based care for their clients

throughout pregnancy, birth, postpartum, and the newborn period. Midwives hold

a high degree of professional responsibility and accountability and must abide

by guidelines and standards appropriate to the clinical context (Ontario

Medical Association & Association of Ontario Midwives, 2005). According to

the Canadian Association of Midwives (CAM) (2015), “Midwifery practice is

informed by research, evidence-based guidelines, clinical experience, and the

unique values and needs of those in their care” (p. 2). This approach aligns with

evidence based medicine (EBM), defined by Guyatt, Rennie, Meade, and Cook (2008) as an approach to

patient care that uses best evidence to guide decision making and emphasizes

the importance of patient values and preferences.

Canadian midwives routinely integrate discussions about risk from the

literature into their conversations with clients (Van Wagner, 2016); further,

midwives must maintain their knowledge and clinical skills to ensure clients

are treated according to current best evidence (College of Midwives of Ontario,

2018). Research on the information behaviour and

evidence based practice (EBP) of Canadian midwives is lacking; however, a

growing number of international studies of midwives and nursing professionals

point to a gap between high level commitments to EBP and the actual practice of

it (Spenceley, O’Leary, Chizawsky,

Ross, & Estabrooks, 2008; De Leo, Bayes, Geraghty

& Butt, 2019). This is a serious issue, as noted by De Leo et al. (2019):

“The evidence‐to‐practice gap in maternity services remains a global issue for

midwives and demands prompt action from both knowledge producers and knowledge

users” (p. 4,234).

A recurring theme in this literature is the importance

of ease-of-information-access on practice. Canadian midwives are expected to

practice evidence based midwifery; however, the extent

to which midwives use and access sources of evidence—such as those found

through systematic reviews, original articles, or databases—is unknown. As

autonomous care providers, midwives have a great need to stay up to date;

however, midwifery associations do not operate libraries for their members.

This contrasts with other professional groups, such as the Canadian Nurses

Association and the College of Family Physicians of Canada, which have created

digital or physical libraries to provide members with access to current,

clinically relevant literature. While many summaries of the literature are

freely available online, key guidelines, policy statements, and committee

opinions from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC)

are published in the Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynecology of Canada which is accessible only to members of

the SOGC by subscription.

To understand the extent to which midwives are able to

satisfy their need for clinically relevant information, we conducted a survey

focused on the types of information sources midwives prefer and their

proficiency with and views about evidence based

practice given the dominant medical model of childbirth in Canada. The aim was

to examine cross-Canada access to and use of evidence based

information by midwives.

Literature Review

Midwifery Practice in Canada

The professionalization and regulation of midwifery in Canada developed

out of the women’s movement of the 1970s to offer an alternative to the

medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth (Parry, 2008). The Canadian

midwifery model of care is based on principles of professional autonomy,

continuity of care, informed choice, choice of birth place, collaborative care,

and evidence based practice (Canadian Association of Midwives,

2015). In this model, a midwife is a responsible and autonomous community-based

provider working in partnership with women and their families to balance

patient values with community standards of practice and current best evidence

(College of Midwives of Ontario, 2018).

Midwifery Education Programs (MEPs) in Canada are direct-entry,

four-year undergraduate degrees leading to a Bachelor of Midwifery or Bachelor

of Health Sciences. There are “bridging” or “pre-registration” midwifery

programs for internationally educated midwives who seek to practice in Canada

(College of Midwives of British Columbia, n.d.). During their time as students,

midwives have access to library databases and electronic resources through

their universities. Upon completion of their programs of study, their access to

university library collections ends or is restricted to alumni privileges or

library walk-in access.

Funding models for midwifery practice vary by province and territory,

but most midwives work as independent contractors under a fee-for-service

agreement with their home province (British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario) or

under a salaried model (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, the Northwest

Territories and Quebec). While no studies have been conducted on

the advantages of each model with respect to library access or use of

clinically relevant information, under the fee-for-service model “midwives have

greater flexibility and fewer bureaucratic barriers to establishing midwifery

practice in diverse geographic settings” (Thiessen, Haworth-Brockman, Nurmi, Demczuk, & Sibley, 2018, p. 7). Fee-for-service

encourages the establishment of midwifery practices at a distance from

hospitals and their onsite libraries and professional networks. In comparison

to other jurisdictions, such as the U.K. and Australia, midwives practicing in

Canada experience a greater degree of autonomy and a greater responsibility to

proactively consult and collaborate with other health professionals (Mallot et al., 2009).

Information Seeking and Evidence Based Practice

Two studies offer useful conceptual frameworks for this project. Leckie,

Pettigrew, and Sylvain (1996) proposed a model of the information seeking of

professionals, taking into account their roles, tasks,

and information needs. As primary care providers, midwives’ roles overlap with

both physicians and nurses, indicating a broad range of information needs. The

model identifies certain constants across professional groups, including the

importance of information access, and it points to a high degree of complexity

in professional work settings, which leads to variability and unpredictability

in information seeking (Leckie et al., 1996). The second model (Spenceley et al., 2008) identifies a range of factors that

shape information seeking activity and outcomes in evidence based nursing

practice: the context of practice, which includes aspects of the individual

practitioner (e.g., education, skills, attitudes), the work setting (e.g.,

training, information resources); the sources of information, which have

attributes, such as availability and trustworthiness; and a number of mediating

factors such as time pressures, the expectations of others, and situational

barriers. Notable themes include the constraints of time and access to

information on the search process, the need for administrative support for EBP,

and the preference for trusted interpersonal sources of information (Spenceley et al., 2008). Both frameworks situate

information practices in context and highlight the awareness of and access to a

range of sources for diverse tasks in complex work settings.

Although studies of information seeking and EBP of Canadian midwives are

lacking, studies of midwives and nurses from the U.K. and Australia indicate

that EBP is consistent with the philosophy of midwifery and is valued by

practitioners (Bayes, Juggins, Whitehead & De Leo, 2019; De Leo et al.,

2019; Fairbrother, Cashin, Conway, Symes, & Graham, 2016; Toohill, Sidebothan, Gamble,

Fenwick, & Creedy, 2017; Veeremah, 2016).

Notably, EBP has been recognized by midwives as a means to reduce the

medicalization of pregnancy and birth, including the overuse of interventions

(De Leo et al., 2019; Kennedy, Doig, Hackley, Leslie & Tillman, 2012;

Miller et al., 2016). At the same time, there is considerable evidence that

midwifery care is not always reflective of EBP guidelines, raising questions as

to the reasons for this gap (Bayes et al., 2019; De Leo et al., 2019;

Fairbrother et al., 2016; Toohill et al., 2017).

A recent integrative review of midwives’ EBP sought to investigate this

issue through close examination of six studies, several of which included both

nurses and midwives (De Leo et al., 2019). The authors identified a number of

themes. Practitioners are aware of EBP and confident with their skills;

however, published information sources are underused, with practices based more

on convention and information gained from patients and other professionals

(Bayes et al., 2019; Fairbrother et al., 2016; Heydari

et al., 2014). For example, in a survey of 297 Australian midwives to evaluate

the uptake of evidence based guidelines on normal

birth, Toohill et al. (2017) found that almost all

respondents were familiar with the guidelines, but only 71% routinely used

them. Three barriers to EBP implementation are widely identified: a lack of

time to find and use evidence based resources (Bayes et al., 2019; Fairbrother

et al., 2016; Toohill et al., 2017; Veeramah, 2016); organizational barriers, such as

resistance to change, lack of support from colleagues, and structural

impediments (Bayes et al., 2019; Heydari et al.,

2014; Toohill et al., 2017; Veeramah,

2016); and limited access to information and computers in the workplace

(Fairbrother et al., 2016; Toohill et al.; 2017; Veeramah, 2016).

Information Literacy and Skills Training

Training medical practitioners to search and appraise high-quality

evidence has long been recognized as an important factor in the provision of

patient care (Guyatt, Meade, Jaeschke,

Cook, & Haynes, 2000). Informed clinicians are able to assess their own

knowledge gaps and formulate effective research questions (McKibbon,

Wyer, Jaeschke, & Hunt,

2008). Lack of access to libraries has been identified as an obstacle to

developing these skills among physicians (Coumou

& Meijman, 2006). In an early survey of the

information needs of 1,715 U.K. nursing professionals, including midwives, Bertulis and Cheeseborough (2008)

found that lack of training in information seeking was an obstacle to applying

evidence in practice. More recent research continues to identify education and

training gaps (e.g. Veeramah, 2016) and the need for

capacity building among nurses and midwives (Fairbrother et al., 2016),

although there is evidence that EBP skills are rising over time. A survey of

Australian nurses and midwives found higher self-reported expertise compared to

earlier studies conducted in the U.K. and Australia (Fairbrother et al., 2016).

However, less than 40% of respondents considered themselves competent or expert

at finding research evidence or using the library to locate information. Rates

of Internet competency were higher, at 63%, a finding supported by additional

research on Australian midwives (McKenna & McLelland,

2011).

Longstanding information practices, including source

preferences, also impact EBP. Ebenezer (2015) reviewed the literature on the

information behaviour of nurses and midwives between

1998 and 2014 and identified a strong preference for gaining information

through human sources. This preference for what Estabrooks

et al. (2005) terms “interactive” and “experiential” sources of information

over formal or “documentary” sources (p. 471) is one of the most frequent

findings in studies of information seeking of nursing and midwives (Bertulis & Cheeseborough,

2008; De Leo et al., 2019; Ebenezer, 2015; Fairbrother et al., 2016; Ricks

& Ham, 2015; Thompson et al., 2001b). Interestingly, this preference for

social information sources does not seem to extend to social media. Dalton et

al. (2014) conducted a mixed methods study of information communication

technology use among Australian midwives and found a high degree of consensus

that social media is an inappropriate and high-risk means of sharing

information in a healthcare context.

Use of pre-appraised evidence, such as practice guidelines,

systematic reviews, and computer decision support systems, continues to impact

the quality of clinical decision making. Guyatt,

Mead, Jaeschke, Cook, and Haynes (2000) noted the

critical importance of pre-appraised evidence for clinicians and observed that,

while not technically practicing evidence based care, the clinical trainees

whom they studied acquired a “restricted set of skills” which included the

ability to track down and use secondary sources of pre-appraised evidence (p.

955). Lafuente-Lafuente et al. (2019) found that

health practitioners used primary evidence infrequently which “suggests that

many professionals probably do not (or are unable to) verify independently, by

their own means, the validity of what is stated in guidelines, or otherwise

what is presented to them as ‘EBM-based’” (2019, p. 5). This is supported by

the work of Fairbrother et al. (2016), which found that articles published in

research, nursing, and medical journals were the least frequently used sources

of information in practice.

Summary

The gap between EBP commitments and reliance upon evidence in every day

practice is widely documented among midwives and the nursing professionals more

generally. This situation persists across the diverse national contexts and workplace

settings in which midwives practice. Relevant models

of information seeking stress the complex and situated nature of the work of

health professionals, in which the roles, tasks, information sources, and work

environments significantly shape and constrain practices. A broad, but

generally consistent, set of barriers to EBP in midwifery have been identified

in studies conducted outside Canada. Among these, access to resources, EBP

literacies and skills, and longstanding information practices are key. Other

factors also emerge as important, notably time, organizational culture, and

receptivity to change. Canadian midwives operate with more autonomy than their

colleagues in the U.K. and Australia, where the majority of studies have been

conducted, which suggests that these findings may not generalize to the

Canadian context.

Aims

Rather than examining the full range of factors known

to shape EBP, the current study focuses on access to libraries and information,

source use, and EBP literacies in the Canadian context, as a first step towards

understanding the local situation and constraints upon EBP. A survey was

designed to investigate the extent to which Canadian registered midwives had

access to and made use of clinically relevant information in practice. The research questions were: How frequently do Canadian midwives use

published information and which sources do they prefer? What challenges do they

encounter in accessing and using information? How do they acquire the

information literacy skills needed to find and apply clinical information and

are those skills well-developed? To provide a more nuanced picture of the status quo, we compare responses across

several factors, including region, work conditions and settings, and access to

libraries.

Methods

Survey Design

The survey instrument (see Appendix) was developed

iteratively by soliciting feedback from library and midwife professionals. The

range and types of questions were developed by using the Association of College

& Research Libraries’ “Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Nursing” (Association of

College and Research Libraries, 2013).

The frameworks of Leckie et al. (1996) and Spenceley

et al. (2008) indicated the importance of collecting contextual data on

demographics, specialization, career stage, and other factors likely to

influence information behaviour. An early version of

the questionnaire was piloted with two registered midwives, both educators, and

a health librarian from British Columbia, Canada. The final version incorporated

feedback from the pilot sessions.

The questionnaire begins by asking for demographic

data to establish the personal and practice context (Q1-6). The next set of

questions (Q7-10) focuses on general access and use of information, including

library memberships and frequency of use of information. Q11 asks about

information source types and use frequency. The list of information sources was

derived from the work of McKibbon et al. (2008).

These categories were not explicitly defined in the questionnaire, but were

presented with illustrative examples, as follows:

·

Summaries (clinical practice guidelines and systematic

reviews)

·

Textbook-like e-resources (UpToDate, AccessMedicine)

·

Studies (original research articles)

·

Print books (monographs, textbooks)

·

Apps

·

Popular websites (WebMD, Mayo Clinic)

·

Social media (Twitter)

Q12 asks participants to rate challenges in applying

clinically relevant information, with a focus on access and literacy skills.

The final set of questions (Q14-16) ask about information literacy training and

competencies. Q14 asks participants to report on their level of expertise in

EBP using a five-point scale ranging from novice to expert, across four

categories of EBP competencies (Q14). Using this data, we calculated an

aggregate metric of EBP competency using the sum of the responses across the

four areas converted to a score out of 10 for ease of interpretation, such that

an expert level of competency across all areas received a top score of 10. This

metric allowed us to compare self-reported EBP competency levels across groups.

The study received approval from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of

British Columbia. The questionnaire was implemented and distributed online

using the Qualtrics platform.

Study Responses and Recruiting

Survey responses were collected during the fall of

2018. The study population was registered midwives in Canada, of which there

were 1,690 at the time of the study (Canadian Association of Midwives, 2018).

CAM is the national body representing midwives and it collects and maintains a

database of registered midwives using data from provincial and territorial

associations and colleges. All registered midwives in the database (n = 1,690) received an invitation from

CAM to participate. To encourage further participation, we distributed

invitations through the Midwives Association of British Columbia’s email list

and the Canadian Registered Midwives Facebook group, which served as reminders

or reinforcements. No compensation was provided for completing the

questionnaire, which took, on average, five to 10 minutes. In total, 218

midwives participated in the survey, representing a 12.8% response rate. Of the

218 questionnaires submitted, 25 were found to be substantially incomplete and

were removed, leaving 193 questionnaires for analysis.

Responses were received from eight provinces and one

territory, but most respondents were from Ontario (40%) and British Columbia

(BC, 39%), followed by Alberta (8%) and Quebec (6%). The mean number of years

of respondents’ midwifery practice was nine, with responses ranging from zero

to 40 years. The educational profile of respondents included 67% (n = 130) holding a Bachelor degree, 23%

(n = 44) Master’s degree, and 4% (n = 7) PhD. A small number held other

credentials. A majority of respondents (71%, n = 137) were practicing full time with 17% (n = 32), practicing part time, 7% (n = 13) non-practicing, many of whom were educators, and 6% (n = 11) reporting some other status,

including those on temporary leaves. We reviewed the responses from the last

two categories and determined that these responses were valid for our purposes,

as these were experienced midwives, whose responses were consistent with the

broader sample.

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of responses by

province and work setting. The majority (68%, n = 131) of respondents were practicing in an urban or suburban

setting, while 26% (n = 51) were

rural and 6% (n = 11) remote. These

categories were provided to participants without definitions, and so were

subject to interpretation. Given the low number of responses from most

provinces, we report comparisons by province only for BC and Ontario in this

report. The BC-Ontario comparisons are not meant to be representative of

conditions across Canada and are not generalizable. Rather, the data analysis

is descriptive in nature and is meant to provide a starting point for

examination and further research.

Table

1

Distribution

of Responses by Region and Work Setting

|

Urban |

Suburban |

Rural |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Alberta |

11 |

3 |

2 |

16 (8%) |

|

|

British Columbia |

36 |

10 |

24 |

3 |

73 (38%) |

|

Manitoba |

3 |

3 (2%) |

|||

|

New Brunswick |

1 |

1 (1%) |

|||

|

NW Territories |

1 |

1 (1%) |

|||

|

Nova Scotia |

1 |

2 |

3 (2%) |

||

|

Ontario |

36 |

19 |

20 |

3 |

78 (40%) |

|

Quebec |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

12 (6%) |

|

Saskatchewan |

1 |

1 (1%) |

|||

|

Multiple provinces |

2 |

1 |

3 (2%) |

||

|

Other |

|

1 |

|

1 |

2 (1%) |

|

Grand total |

95 (49%) |

36 (19%) |

51 (26%) |

11 (6%) |

193 |

Results

Library Membership

We asked participants if they held membership in an

academic or hospital library, based on the assumption that library privileges,

such as access to bibliographic databases and electronic resources, require

library membership. Figure 1 summarizes responses. Overall, 67% (n = 129) of respondents reported some

type of academic library membership and 33% (n = 64) reported having no library membership (or unsure). Of those

who had membership, 53% (n = 68) had

access through a university as a student, employee, or faculty member; 57% (n = 74) through a hospital; and 9% (n = 12) through a college or private

library. Many had access through multiple avenues. Several respondents

indicated in their comments that they held alumni library privileges, which

were described as “limited” or due to expire one year after graduation. Others

said they gained access to academic collections through use of their

colleagues’ or partners’ passwords or via credentials gained through other

professional associations. One respondent added the comment that “hospitals

refuse midwives access.”

Figure 1

Library membership (academic or hospital

libraries).

We compared the rates of library membership across

different geographic regions. A higher percentage of respondents from BC (74%)

reported having membership access compared to those from Ontario (65%). With

respect to work setting (Figure 2), rates of library membership in urban work

environments were highest at 72% followed by suburban at 69%, remote at 64%,

and rural at 57%. Midwives with graduate degrees reported higher levels of

library membership (78%) compared to those with undergraduate degrees (62%).

There was no difference between those who reported working full time or part

time. In a separate question, we asked if respondents used public libraries as

a resource for their clinical information needs. This proved to be highly

uncommon, with 96% of respondents indicating that they very rarely or never use

public libraries to stay informed for practice.

Figure 2

Library membership by

work setting (percent).

Use of Clinically Relevant Information

Participants were asked how frequently they refer to clinically relevant

information in their midwifery practices. The most common response was:

frequently – several times a week (65%), followed by occasionally – a few times

a month (18%), and very frequently – several times a day (14%). Figure 3

compares the frequency of information usage by those with and without

membership in an academic or hospital library. Not surprisingly, a higher

percentage of those with access to a library reported using information at a

high frequency, while those without access were more likely to use information

occasionally, rarely, or very rarely.

Figure 3

Comparison of information use frequency by

library membership.

Group comparisons were made based on high-frequency information usage

(defined as the percentage of those who reported using information frequently

or very frequently):

·

85% (n = 62)

of respondents from BC were high-frequency users compared to 76% (n = 59) in Ontario;

·

85% (n = 81)

of respondents in urban settings were high-frequency users compared with 72% (n = 26) in suburban, 73% (n = 37) in rural, and 82% (n = 9) in remote settings;

·

82% (n = 113)

of respondents working full time were high-frequency users compared with 63% (n = 40) of those working part time;

·

88% (n = 45) of respondents with graduate

degrees were high-frequency users compared with 77% (n = 96) of those with undergraduate degrees.

Participants were asked to report on their use of nine different types

of information sources in terms of frequency. The results, presented in Figure

4 showing higher percentages in darker shading, indicate summaries and

colleagues are used most frequently as information sources.

Figure 4

Heat map of information source frequency of use (percent).

We were interested in the impact of library access on

the types of information sources consulted. We focused our analysis on a subset

of all information source types, including those we thought would be most

affected. The results, presented in Table 2, showed some interesting patterns.

At the highest level of frequency, those without library access reported less

frequent use of summaries, colleagues, and textbook-like e-resources and more

use of websites than colleagues with library access. Research articles were

used less frequently by those without access, although this shows up in the frequent

(lower) and rare (higher) use categories. Lack of membership did seem to

influence resource use patterns, but it did not prevent most midwives from

using a range of resource types on a regular basis.

Table 2

Comparison of Information Source Frequency of

Use (Percent) by Library Membership (Yes/No)

|

Very Frequently |

Frequently |

Occasionally |

Rarely |

Never |

||||||

|

Information Sources |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Summaries |

48 |

40 |

44 |

48 |

8 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Colleagues |

40 |

31 |

51 |

48 |

8 |

17 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Textbook-like e-resources |

21 |

10 |

37 |

28 |

28 |

33 |

10 |

17 |

5 |

12 |

|

Original research articles |

10 |

10 |

36 |

20 |

43 |

45 |

11 |

22 |

1 |

3 |

|

Popular websites |

5 |

15 |

33 |

27 |

41 |

42 |

17 |

10 |

5 |

7 |

Borrowed Library Access

In the final open-ended question in the survey, a number of responses

raised concerns that midwives are forced to ask for help in accessing essential

information. One midwife commented “I always meet my information needs by using

online resources or by asking my senior student to use her online connection to

university libraries to locate resources…” Another stated, “I don't have other

means of ‘official’ access but I frequently use a family member’s library card

to access the University library.” Other respondents mentioned using a

partner’s university library membership and a friend’s login to UpToDate. Many

midwives noted that they had alumni library privileges but commented on the

limitations of such access, especially in cases where such privileges do not

extend to online databases.

Library Skills and Evidence Based Practice Competencies

Question 14 asked participants with multiple choice

and an optional short answer question if they had ever received library skills

training. Twenty-eight percent reported that they had never received training

(or could not remember). Overall, 54% reported receiving some library skills

training during their midwifery education and training, and the remaining 18%

had exposure to this training through other means. Those who made additional comments

for this question noted that such training was “limited,” or superficial: “we

touched on it.” Several respondents noted that they received more training in

library skills during the acquisition of degrees unrelated to midwifery. Other

comments highlighted that training was brief, years ago, and that the specifics

of the instruction were difficult to recall:

·

“This training was 10-15 years ago. A lot has changed

since then.”

·

“But I can’t call on that knowledge even though it’s

been 7-10 years.”

·

“20 years ago, too long ago”

Participants reported interest in receiving library

skills training; however, a number of comments indicated that training would

not be useful without access to library resources.

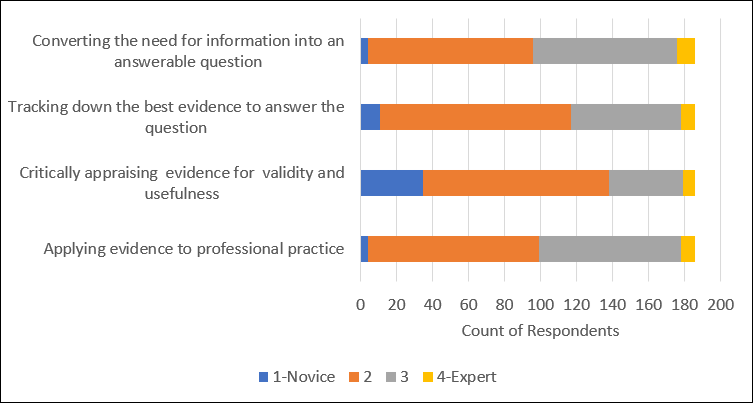

Results of the EBP competency question summarized in

Figure 5 indicate that very few respondents identified as expert in any of the

EBP competency areas, and the majority of responses were in the middle points

of the scale. The highest levels of expertise were reported for converting the

need into an answerable question and application of evidence to practice and

the lowest levels for critical appraisal of evidence.

Using an aggregate metric of EBP competency, we

compared competency scores across groups. Self-reported competency scores

increase with experience, with mean scores of 5.7 for those with less than 5

years in practice; 6.0 for those with between 5 and 19 years, and 6.5 for those

with 20 or more years. Similarly, higher competency levels are reported for

those with graduate level education (6.4 for Master’s and 7.1 for PhD) as

compared to those with undergraduate degrees (5.7). Respondents with library

access report higher levels of expertise (6.0) than those who do not report

access to a library (5.5).

Challenges to Using Clinically Relevant Research in Practice

Participants were asked to indicate their level of

agreement with a set of five challenges as factors in their own practice.

Figure 5 summarizes the results, showing the percent of all respondents who

indicated agreement or strong agreement with each statement. Lack of access to

information showed the highest level of agreement (53%), followed by the

difficulty in judging the quality of research (41%), which reinforces the low

self-reported competency in this area.

Further analysis regarding the challenges associated

with lack of information access suggests that some variation exists across

groups:

·

62% (n = 31)

of midwives working in rural settings agreed that information access was a

challenge in comparison with 47% (n = 45)

of those working in urban settings;

·

66% (n = 51%)

of early career midwives agreed that information access was a challenge in

comparison with 29% (n = 6) of those

with more than 20 years’ experience;

The high costs of paying to download articles and buy

memberships to point of care tools such as UpToDate were mentioned repeatedly

in response to the open question. Comments included the following:

- “I think the biggest limitation is access to

information. SOGC guidelines, UpToDate and several other critical sources

are now fee for service and some midwifery clinics will not pay these fees,

leaving the midwives at a disadvantage for relevant data.”

- “Subscriptions to library databases is very

expensive particularly for small practices or individual midwives.”

- “The main barrier to accessing medical libraries

and online journals is cost. For a midwifery clinic or individual midwife

to afford this they need to pay midwives adequately.”

Figure 5

Levels of reported

expertise across EBP competency areas.

Figure 6

Levels of agreement with

challenges to using clinically relevant research in midwifery practice.

Discussion

This study set out to understand the extent to which Canadian midwives

have access to and make use of clinically relevant information in practice. One

third of survey respondents reported having no library membership. Urban

midwives and those with graduate degrees reported higher levels of library

membership. This level of access is consistent with Veeremah’s

(2016) study, in which one third of respondents reported limited access to

information, and it affirms prior research indicating that access to

information continues to be a challenge in professional contexts (Leckie et

al., 1996; Spenceley et al., 2008), even as digital

and mobile information technologies proliferate. Results further show that

those respondents without library access were less likely to be frequent users

of clinically relevant information and were more likely to refer to websites,

which undergo less quality control than published summaries, textbook-like

e-resources, or research articles. Considering the high degree of

responsibility and technical knowledge required in midwifery, this finding is

concerning, as it brings into question the quality, consistency, and equity of

care across settings. While other health practitioners in Canada enjoy access

to digital libraries offered by their colleges and associations, midwives do

not benefit from such a program, which could be considered a basic component of

EBP.

More than 50% of survey respondents agreed that access to information is

an obstacle to EBP, with more limited agreement that finding, using, and

evaluating clinically relevant information is challenging. A surprising result

was that respondents reported finding creative ways to access the information

they needed for EBP by bypassing paywalls and borrowing memberships. One

respondent linked this issue of information access with the broader issue of

hospital integration and hospital privileging, by indicating that they were denied

access to information by the hospital. If midwives are barred from using

library services by virtue of not being “staff” and holding “privileges,” this

bureaucratic barrier raises ethical implications for patient safety and should

be addressed as a matter of urgency. In this context, “borrowing” access

privileges, which breaks licensing agreements and constitutes a misuse of

library systems, can be viewed as a form of activism designed to redress an

imbalance of power and privilege within the healthcare field. While this study

did not examine the impact of organizational factors on EBP, studies such as

that carried out by Bayes et al. (2016) show that midwives are vulnerable to

opposition to EBP from hospitals, colleagues, and superiors, in part because

EBP guidelines may run counter to dominant medicalized approaches to childbirth

(Toohill et al., 2017). This perspective should be

explored further, as the role of power and privilege in information seeking and

EBP is largely absent from prior research and existing conceptual frameworks

(e.g. Leckie et al., 1996; Spenceley et al., 2008),

and it may offer new insights, particularly for the study of midwifery in

Canada.

The majority of midwives reported difficulty judging

the quality of the evidence. This finding is echoed in studies by Fairbrother

et al. (2016) and by Ross (2010) who reported that nurses had difficulty

understanding articles and had insufficient skills critiquing the literature.

Midwives indicated that the information literacy skills they received during

their education was limited and, in many cases, stale. However, midwives with

advanced degrees (graduate, PhDs) ranked themselves more highly on evidence based practice competency scales than their

undergraduate-holding colleagues. Guyatt et al.

(2000) considered the skills of critical appraisal of primary studies to be

invaluable, stating that health care providers who had these skills would be

better able to identify when attempts to influence practice were made based on

evidence (or to justify childbirth interventions). Lafuente-Lafuente

et al. (2019) echo this sentiment, stating that practitioners who used primary

studies infrequently were less able to independently verify the guidance

provided in clinical practice guidelines. In the context of increasing

childbirth interventions, midwives with quality appraisal skills of original

literature may be better able to identify when clinical guidelines are out of

date, biased, or have used poor methodology. This finding points to the fact

that increasing the accessibility of information is only one component of a

much broader set of challenges, which includes the need for training and

capacity building.

Results of this study reinforce previous findings that clinical practice

guidelines are an essential resource for clinicians. In total, 91% of midwives

in this study reported frequent use of summaries such as those published by the

Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada, the Association of

Ontario Midwives (AOM), and the Perinatal Services of British Columbia.

However, clinical practice guidelines developed by the SOGC are currently

behind a membership firewall, despite their relevance for maternity care

professionals. Membership in SOGC is fee-based ($160 per year) and many midwives

in this study indicated that they did not have access to these guidelines. The

College of Midwives of British Columbia recently rescinded their clinical

practice guidelines (which were freely available on their website), and no

longer create or maintain them due to a lack of funding and the existence of

guidelines from national expert bodies such as the SOGC and the Perinatal

Services of British Columbia (R. Comfort, personal communication, July, 10,

2019). This decision is concerning in light of the findings of this study and

because midwife-specific guidelines address the person-centered model of care

that characterizes Canadian midwifery.

The opinions of trusted colleagues were the second most common

information source used by surveyed midwives, which is not surprising given

that this is one of the most consistent themes in the information-seeking

research on professionals, nurses, and midwives (De Leo et al., 2019; Leckie et

al., 1996; Spenceley et al., 2008). While this

research did not examine why this is the case, it is clear from the wider

literature that interpersonal sources of information are valuable in the

context of EBP for a number of reasons, including that people provide

information that is contextualized and experience based, and in some cases they

perform a translational role, by sharing information in a form that is more

easily understood or made more relevant for a particular audience (Thompson et

al., 2001b). Given this preference for collegial information sharing,

mentorship or peer-based training models for EBP in midwifery may prove to be

effective (Fairbrother et al., 2016). At the same time, the reliance on

colleagues as information sources reinforces the role that a supportive

organization plays in enabling EBP, including midwife leaders able to champion

change (Bayes et al., 2019; Spenceley, et al., 2008).

This study has focused only on select components of the conceptual

frameworks developed by Leckie et al. (1996) and by Spenceley

et al. (2008), notably, aspects of the individual (education, work experience,

skills); the work setting (region, employment status); the sources of

information (accessibility, source type); and the outcomes (information behaviours). Results are based on limited self-report data

and statistical tests were not conducted. Therefore, these results are not

generalizable. A more comprehensive study would need to consider additional

features, notably, the impact of organizational factors and time pressures,

which are known to influence EBP. Given the lack of prior research in the

Canadian context and the unique nature of midwifery practice in Canada, further

research is needed to validate and extend these findings. One contribution of

this study is the identification of information-seeking strategies that sidestep

existing systems and norms in order to meet needs, and which may reflect

structural barriers and power imbalances that are not currently addressed in

these models.

Conclusion

Canadian midwives, as experts in physiologic birth, enjoy an expanded scope

of practice that requires frequent and ongoing consultation with information.

As professionals committed to EBP, access to high-quality information would

seem to be a given; however, the results of this survey indicate that a substantial number of midwives are practicing

without such access. Clinical practice guidelines support the work of midwives

but are inaccessible to many midwives due to paywalls. Respondents lacked

confidence in evidence

based practice and

reported critical appraisal as an area for development. While no Canadian

universities currently offer higher degrees in midwifery, it may be that future

offerings of advanced midwifery programs would have a beneficial effect on evidence based practice proficiency as midwives with

advanced degrees had higher self-reported EBP expertise. Coordinating access to

digital biomedical collections or removing barriers to midwife access of these

collections is one way that hospitals, health authorities, and their libraries,

provincial, or national associations could help midwives

practice EBP. Hospital and academic libraries should prioritize the information

needs of student and practicing midwives and identify ways to foster use of

library resources through educational interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those midwives who responded to the

questionnaire and shared their experience and insights. We appreciate the

support of the CAM for allowing us to recruit via their listserv, and to Cathy

Ellis, RM, Alixandra Bacon, RM, and Brooke Ballantyne

Scott, Manager of Library Services, Royal Columbian Hospital, who provided

comments and a review of the survey instrument.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2013).

Information literacy competency standards for nursing. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/nursing

Bayes, S., Juggins, E., Whitehead, L., & De Leo, A. (2019).

Australian midwives’ experiences of implementing practice change. Midwifery, 70, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.12.012

Bertulis, R., & Cheeseborough, J. (2008). The

Royal College of Nursing’s information needs survey of nurses and health

professionals. Health Information and

Libraries Journal, 25(3),

186–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00755.x

Canadian Association of Midwives. (2015). Canadian

midwifery model of care [position statement]. Retrieved from https://canadianmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FINALMoCPS_O09102018.pdf

Canadian Association of Midwives. (2018). Midwifery care

for all: Building the profession, annual report, 2017-2018. Retrieved from https://canadianmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Annual-Report-2017-2018.pdf

College of Midwives of British Columbia (n.d.).

Recognized midwifery education programs. Retrieved from https://www.cmbc.bc.ca/registration/inter-provincial-registration/recognized-midwifery-education-programs/

College of Midwives of Ontario. (2018). Professional

standards for midwives. Retrieved from https://www.cmo.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Professional-Standards.pdf

Coumou, H. C., & Meijman, F. J. (2006). How do

primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 94(1),

55–60. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16404470

Dalton, J. A., Rodger, D. L., Wilmore, M., Skuse, A. J., Humphreys, S., Flabouris,

M. & Clifton, V.L. (2014). “Who’s afraid?”: Attitudes of midwives to the

use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for delivery of

pregnancy-related health information. Women

and Birth, 27(3), 168-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2014.06.010

De Leo, A., Bayes, S., Geraghty, S. & Butt, J.

(2019). Midwives’ use of best available evidence in practice: An integrative

review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28, 4225-4235. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15027

Ebenezer, C. (2015). Nurses’ and midwives’ information

behaviour: A review of literature from 1998 to 2014. New Library World, 116(3/4), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-07-2014-0085

Estabrooks. C. A, Rutakumwa, W., O’Leary, K. A., Profetto-Mcrath, J., Milner, M., Levers, M. J. &

Scott-Findlay, S. (2005). Sources of practice knowledge among nurses. Qualitative Health Research, 15(4), 460-476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304273702

Fairbrother, G., Cashin, A., Conway, R., Symes, A.,

& Graham, I. (2016). Evidence based nursing and midwifery practice in a

regional Australian healthcare setting: Behaviours,

skills and barriers. Collegian, 23(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2014.09.011

Guyatt, G., Meade, M.,

Jaeschke, R., Cook, D., & Haynes, R. (2000).

Practitioners of evidence based care. Not all

clinicians need to appraise evidence from scratch but all need some skills. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 320(7240),

954–955. https://doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7240.954

Guyatt, G., Rennie, D., Meade, M. & Cook, D. (2008). Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based

Clinical Practice (2nd edition). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Heydari, A., Mazlom, S., Ranjbar,

H., & Scurlock‐Evans, L. (2014). A study of Iranian nurses and midwives’

knowledge, attitudes, and implementation of evidence‐based practice: The time

for change has arrived. Worldviews on

Evidence Based Nursing, 11(5),

325–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12052

Kennedy, H. P., Doig, E., Hackley, B., Leslie, M. S.,

& Tillman, S. (2012) “The midwifery two step”: A study on evidence-based

midwifery practice. Journal of Midwifery

& Women’s Health, 57(5), 454-460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00174.x

Lafuente-Lafuente, C., Leitao, C., Kilani,

I., Kacher, Z., Engels, C., Canoui-Poitrine,

F., & Belmin, J. (2019). Knowledge and use of

evidence-based medicine in daily practice by health professionals: A

cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 9,

1-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025224

Leckie, G., Pettigrew, K., & Sylvain, C. (1996).

Modeling the information seeking of professionals: A general model derived from

research on engineers, health care professionals, and lawyers. The Library Quarterly, 66(2), 161-193.

Malott, A., Davis, B., McDonald, H., & Hutton, E. (2009). Midwifery

care in eight industrialized countries: How does Canadian midwifery compare? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 31(10),

974–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34328-6

McKenna, L. & McLelland, G. (2011)

Midwives’ use of the Internet: an Australian study. Midwifery, 27(1), 74-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2009.07.007

McKibbon, A., Wyer, P., Jaeschke, R., &

Hunt, D. (2008). Finding the evidence. In G. Guyatt,

D. Rennie, D. Cook, M. Mead & American Medical Association (Eds.), Users Guides to the Medical Literature

(pp. 29-58). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Miller, S., Abalos, E., Chamillard, M., Ciapponi, A., Colaci, D., Comandé, D., … Althabe, F. (2016). Beyond too

little, too late and too much, too soon: A pathway towards evidence-based,

respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet,

388(10056), 2176-2192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6

Ontario Medical Association & Association of

Midwives of Ontario (2005). A joint statement of professional relations between

obstetricians and midwives in Ontario [position statement]. Retrieved from https://www.ontariomidwives.ca.

Parry, D.C. (2008). “We wanted a birth experience, not

a medical experience”: Exploring Canadian women’s use of midwifery. Health Care for Women International, 29(8-9), 784-806. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330802269451

Ricks, E., & Ham, W. (2015). Health information

needs of professional nurses required at the point of care. Curationis, 38(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1432

Ross, J. (2010). Information literacy for

evidence-based practice in perianesthesia nurses:

Readiness for evidence-based practice. Journal

of Perianesthesia Nursing, 25(2), 64-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2010.01.007

Sackett, D., Strauss, S., Richardson, W., Rosenberg,

W., & Haynes, R. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM

(2nd ed.) Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Spenceley, S.M., O’Leary, K.A., Chizawsky, L.L.K.,

Ross, A.J., & Estabrooks, C.A. (2008). Sources of

information used by nurses to inform practice: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies,

45(6), 954-970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.06.003

Thiessen, K., Haworth-Brockman, M., Nurmi, M., Demczuk, L., & Sibley, K. (2018). Delivering midwifery:

A scoping review of employment models in Canada. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada,

42(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2018.09.012

Thompson, C., McCaughan, D., Cullum, N., Sheldon, T., Mulhall, A., &

Thompson, R. (2001). Research information in nurses

clinical decision making: What is useful? Journal

of Advanced Nursing, 36(3),

376-388.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01985.x

Toohill, J., Sidebotham, M., Gamble, J., Fenwick, J., & Creedy, D.

(2017). Factors influencing midwives’ use of an evidenced based Normal Birth

Guideline. Women and Birth, 30(5), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.03.008

Van Wagner, V. (2016). Risk talk : Using evidence

without increasing fear. Midwifery, 38, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.009

Veeramah, V. (2016). The

use of evidenced-based information by nurses and midwives to inform practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(3–4), 340–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13054

Appendix

Survey Instrument

- How many years have you been practicing as a

midwife?

·

0-40

- What is your highest degree earned?

·

Bachelors

·

Masters

·

PhD

·

Other

- Which province or territory do you practice in

predominantly?

- What is your status as Registered Midwife?

·

Full time

·

Part time

·

Non-practicing

·

Other

- Are you a midwifery

educator? (preceptor, NRP instructor, faculty position etc.)

·

Y/N

- In what setting are you

currently practicing? Select the best answer.

·

Urban

·

Suburban

·

Rural

·

Remote

- How often do you refer

to clinically-relevant, external information in the practice of midwifery?

(guidelines, manuals, books, websites)? 6-point Very frequently – Never

- Do you hold membership

in an academic library or hospital library? (Check all that apply)

·

Yes, through an academic library at a university where

I am faculty/employed/studying

·

Yes, through membership in a College or private

library (e.g. CMA, CFPC, CNA)

·

Yes, through my hospital (privileges/staff)

·

No, I do not hold membership in an academic/hospital

library

·

Unsure

·

Other

- If you answered Yes to

the above, how often do you access clinically-relevant information through

your academic or hospital library membership? (7 point Very frequently –

Never, N/A)

- How often do you visit

your local public library to find clinically-relevant information for

midwifery practice? (6 point Very frequently – Never)

- Please rank use of the following information

sources and modes of delivery in your midwifery practice:

·

Manuals (NRP, ALARM)

·

Colleagues

·

Studies (primary studies)

·

Popular websites

·

Print books

·

Social media

·

Summaries (clinical practice guidelines, systematic

reviews, algorithms)

·

Textbook-like e-resources (UptoDate,

DynaMed)

·

Apps

- Please rank the

challenges to using clinically relevant research in your practice

·

Lack of information access

·

Difficulty in judging the quality of the research

evidence

·

Difficulty relating research evidence to clinical

practice

·

Difficulty understanding statistical terms or jargon

·

Lack of skills in using specialized search tools

- The Association of

College and Research Libraries (2016) recognizes that information sources

must be evaluated “to acknowledge biases that privilege some sources of

authority over others, especially in terms of others’ worldviews, gender,

sexual orientation, and cultural orientations.” How relevant do you think

this statement is to the practice of midwifery? (5 point Very relevant –

Completely Irrelevant)

- Sackett et al. (2000)

describe evidence-based medicine as “the integration of best research

evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” Based on this

statement how do you rate your competence in the following: (5-point

Expert – Novice)

·

Converting the need for information (about prevention,

therapy, diagnosis) into an answerable question

·

Tracking down the best evidence with which to answer

that question

·

Critically appraising that evidence for its validity

(closeness to truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

·

Applying evidence to the context of professional

practice

- Have you ever received

library skills training (i.e., Boolean operators, truncation, controlled

vocabularies, databases)? Check all that apply:

·

Yes, during my midwifery education and training

·

Yes, through my hospital or place of work

·

Yes, during the acquisition of a post-midwifery credential

·

No or cannot remember

·

Other (please elaborate)

- How interested would

you be in receiving library skills instruction relevant to midwifery?

(5-point Very Interested – Uninterested)

- Would you like to share

more detail about any of the above questions?