Research Article

Assessment on a Dime: Low Cost User Data Collection

for Assessment

Eric Dillalogue

Assistant Director of

Operations

Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books

and Manuscripts

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Michael Koehn

Director for Library

Operations

Augustus C. Long Health

Sciences Library

Columbia University Irving

Medical Center

New York City, New York,

United States of America

Received: 6 May 2019 Accepted: 27 Mar. 2020

![]() 2020 Dillalogue and Koehn. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Dillalogue and Koehn. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29582

Abstract

Objective

–

This article describes the construction and use of a low cost

tool for capturing user demographics in a physical library.

Methods – At

the Health Sciences Library of Columbia University Irving Medical Center, we

created the Tap In/Tap Out tool to learn about the demographic details of our

library visitors, such as their status, school affiliation, and department. The

Tap In/Tap Out tool was implemented twice for two weeks in 2013 and 2017, with

users voluntarily tapping their campus ID when entering and leaving the

library. We checked campus ID numbers against university databases to fill in

demographic details of the library users.

Results – We

constructed the Tap In/Tap Out tool using a Raspberry Pi and RFID card readers

mounted on a foam board poster and placed near the library entrance.

Participation in the Tap In/Tap Out tool ranged from 5-7% of the library gate

count numbers during the survey periods. Though low, this participation

provided a useful indication of user demographics that helped to strengthen

library discussions with university administration. The 2013 survey results,

which showed that the library space was actively used by students from all the

constituent Medical Center schools, were used to support funding

justifications. The 2017 survey results, which showed continued library usage,

were used to illustrate the value of the library to the Medical Center community.

Conclusion –

The Tap In/Tap Out tool was inexpensive to implement and provided more

information about library visitors than gate counts alone. Findings from the

Tap In/Tap Out results were used to demonstrate library usage and justify

funding. We describe how other libraries might create and implement the tool to

capture greater levels of detail about the users visiting their spaces.

Introduction

Assessment is an important function in any library for evaluating usage,

resource effectiveness, staff efficiency, and myriad other elements for

internal and external purposes. Though assessment is a constant point of

discussion today, it is not a new initiative for libraries. In 1976, the

Association of Research Libraries laid out the need to assess all aspects of

the library because “concern has increased for determining library output or

effectiveness – how well the library actually meets users’ needs. This concern

relates to the library’s responsibility to serve, with limited budgets, groups

widely diversified … [and] by the need to further justify activities to the

parent institution, to evaluate possible new services, and to predict and

influence change” (p. 1).

Traditionally, libraries have used gate counts as one way to assess

space use – how many patrons entered or exited the space at a given time on a

day. Though this data provides insight into the level of library foot traffic –

with characteristic spikes for testing periods and dips during breaks – the

data does not include information on who

used the space. As Nackerud, Fransen,

Peterson, and Mastel (2013) note, there are important

questions that go unanswered if all we know are numbers: “Who are these

students? What colleges do they represent? Does the library reach a majority of

students in some measurable way?” (p. 140). Of particular interest to libraries

are the demographic details of visitors: their university affiliation, status,

school, department, and/or program. These demographic details allow libraries

to demonstrate value to the wider campus through assessment efforts.

However, gathering patron demographic information can be difficult. Some

libraries have ID-swipe gate systems that consistently record demographic

information, but libraries without this gate functionality face a technological

hurdle. To address this issue, we have developed a tool called “Tap In/Tap Out”

to acquire patron demographics at the entry and exit points of the library. We

will discuss the technical aspects of setting up a Tap In/Tap Out tool, the

data we collected, and how we used that information.

The purpose of this article is to present a low cost

user information capture tool that can be adapted for assessment in many types

of settings. We discuss the tool’s use in a pre-renovation environment, with

the acquired information used to demonstrate library usage across five health

sciences schools and to make a case for funding, and in a post-renovation

environment to explore current user demographics. Though there are some

limitations to the Tap In/Tap Out tool, we believe it provides an innovative

method to assess library usage at the point of entry. This paper describes how

to create and implement the Tap In/Tap Out tool so other libraries that lack

the technological infrastructure or financial means to install swipe-card entry

gates can capture greater levels of detail about the people using their spaces.

Literature Review

A common way to assess and compare library usage is to

count the number of users who visit a library, most often done with gate counts

at the entry point(s). Whether using mechanical turnstiles or infrared

beam-counting gates, gate counts “remain one of the most widely accepted

methods for measuring facility use” (Stewart, 2011, p. 539). Typically,

commercial providers supply gates that combine methods of tracking library

materials (e.g., books) and counting people.

But gate counts with any device only provide

information on how many users enter or exit a space and do not include

information on who the users were nor how long they stayed in the library

space. The lack of patron details has been partially addressed in newer gate

technologies that require a user to swipe their ID for access, allowing the

library to count the number of visitors and, when connected to a database of

patron information, access additional demographic details on those visitors

(Jones, 2011). For example, Scarletto, Burhanna, and Richardson (2013) were able to determine the

demographics of users visiting the library during overnight hours by capturing

swipe-card entries at the library’s entrance and sending “identification

numbers of users during the study period … to the University Research, Planning

and Institutional Effectiveness (RPIE) office for associated demographic data

relating to department, major, grade point average, class standing,

international status, home campus, ethnicity, and gender” (p. 373). Using that

information, the library had a more informed view of their overnight users.

However, swipe-card entry gates are expensive and not

feasible for all libraries. To address the need for more user information to

assess library usage, some libraries are using alternate demographic data

collection methods to get a better understanding of their spaces and users. For

example, Dotson and Garris (2008), employed building

surveys to measure usage of their library’s physical resources. These surveys

were used to “examine exactly what physical resources people are using” and to

“use that information to make improvements to existing resources, services and

spaces” (p. 11). Nackerud, Fransen,

Peterson, and Mastel (2013) were able to capture

unique patron identifiers via computer log-ins and circulation transactions,

combining that data with other points of patron access, to analyze user

demographics and determine which students were (or were not) using the library.

For example, using this method they found “that 77 percent of undergraduate

students and 85 percent of graduate students made use of the library during the

Fall 2011 semester” (p. 142). And for those undergraduate students who did

visit, Nackerud et al. found that they “consistently

had higher semester GPAs than students who made no use of the library” (p.

140). And Lux, Snyder, and Boff (2016) used

touch-based surveys loaded on iPads to capture patron demographics and reasons

for coming to the library. The authors found that graduate students and faculty

used the library to either study individually or to access library materials;

whereas undergraduate students primarily visited to study alone or as part of a

group (p. 112). Similarly, there are studies that include observations and

seating sweeps, but these do not provide details on who the users are in the

space; hence, those studies are not included here.

Any collection of user data also raises privacy concerns. As the

American Library Association notes, “users expect … to have their personally

identifiable information and library-use data protected and kept private and

confidential …” and “libraries should collect and store only personally

identifiable data required for specific purposes that are disclosed to the

users” (2002). Privacy has been described as a “tightrope” along which we walk

and requires “a type of judgment call by a library staff member or

administrator which pits the mission and goals of the library against user

privacy” (Coombs, 2004, p. 495). There is a wealth of thoughtful literature on privacy

in libraries and we will not explore it all here, but we do address data

collection issues with regards to the Tap In/Tap Out tool in the Methods

section.

We find that Jones’ statement from nearly a decade ago is still true,

that there is an “absence of literature describing tools for analysis of and

practical use for swipe-card data, particularly in informing library decisions

…” (2010, p. 12). This paper adds to the literature on swipe-card data by

presenting the Tap In/Tap Out tool. This tool bridges the gap between the raw

numbers from an infrared beam gate counter and the detailed user information

from a swipe-card entry system, while keeping costs and staff involvement

low.

Background/Aims

As do many libraries, the Health Sciences Library at Columbia University

struggled to understand the populations who used its space. As the primary

provider of study space on the Columbia University Irving Medical Center

(CUIMC) campus, library staff could determine that most library space users

were students. Beyond that, assumptions were made about the demographics of

users in the space (status, school affiliation, program, etc.) based on staff

observations and anecdotal evidence, but these assumptions were not backed up

by quantitative evidence.

Space is a highly valued commodity at CUIMC. The library lost square

footage at several points in its history.

For example, a renovation completed in 2009 converted more than 20,000

sq. ft. of library stacks space into classroom space. The library needed to

demonstrate that students, faculty, and staff of all programs used the

library’s remaining physical space. This would allow the library to advocate

for enhanced maintenance of and upgrade to these spaces, which had seen only

minor updates since the building was completed in 1975.

Other libraries at Columbia University installed entry gates activated

by the University’s RFID badges, gaining useful demographic information about

the users entering their spaces. Rather than just a raw gate count, these

libraries had a wealth of demographic information. Users could be identified by

their university affiliation (student, faculty, or staff), their school or department, and their

enrolled program. In addition, time of day data was available for each entry.

This additional level of detail allows those libraries with swipe card entry

gates to get more information than just a gate count – they can understand how

users from different university departments or programs use their spaces and

how the makeup of users changes over time. These data points help to strengthen

library decision making and the case for funding.

Administrators at the Health Sciences Library examined the library’s

setting and determined that, aside from the financial costs of implementing

swipe-card access entry gates, the logistics of the library’s location created

challenges as well. The library was located immediately behind entry gates for

the Hammer Health Sciences Center, so there was no security benefit added

through entry gates. In addition, since space users had swiped into the

building just seconds before entering the library, staff thought space users

would be frustrated by the need to swipe in again, especially given the

challenges users were having with the existing gates.

But the basic concept of swipe-to-enter provided a starting point. The

library already had RFID card readers in use for circulation transactions at

the service desk. If similar readers could be coupled with an inexpensive data

collection device, it might be possible to produce similar demographics to

other libraries’ entry gates at a much lower cost. The Raspberry Pi (RPi) single board computer seemed like an ideal candidate

for our data collection needs.

To avoid frustrating users of the space, data collection had to be

voluntary and time limited. The resulting data would be a sample, but it would

be an indicator of usage patterns in the space, and the information returned

would be far more detailed than the library’s existing gate count data. Staff

realized that the same methodology could be used to also collect exit data,

providing length-of-stay data. Thus the Tap In/Tap Out

tool was created.

Methods

We designed the Tap In/Tap Out tool as a type of

survey data collection device. Specifically, this tool was created to take a

snapshot of the number and types of patrons entering and exiting the library

during a short sampling period. That Tap In/Tap Out tool follows the concept of

a “survey” defined by Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2007) as a method to “gather

data at a particular point in time with the intention of describing the nature

of existing conditions …" (p. 205). Participation was voluntary. We were

not seeking statistical significance in collecting the information, but rather

data representative of use and demographics, providing more details than

existing gate counts or patron in/out numbers. We used historical gate count

information, academic calendars, and staff knowledge to choose the two weeks

for surveying, selecting a time in the middle of the semester that avoided any

school breaks or testing days. The study was conducted twice, once in 2013

(pre-renovation of the library) and once in 2017 (post-renovation). In addition,

each iteration included two rounds of data collection, once in the spring and

once in the fall semesters. The exact dates in 2013 and 2017 were different due

to the academic calendars in those years.

The study was designed as a management study of the

library’s patrons, rather than as a research study to develop generalizable

knowledge. As such, it is not human subject research and did not require IRB

approval (Columbia University, 2012). Information on the purpose of the study,

use of information collected, and contact information for additional details

were posted at the point of participation. (See Appendix A for posted text.)

Patron participation was voluntary. Staff were instructed to encourage

participation during the study, but patrons could, and often did, enter and

leave the library without participating. This intervention was the extent of

participation by front line staff, fulfilling the goal of low staff

involvement.

Several factors were considered when examining the

risk of disclosure of collected data. ID card numbers and date/time data stored

on RPi could only be linked to an individual through

secure university databases. Access to these databases is restricted to

employees with a legitimate business need. The work to link the ID card numbers

to user demographics was performed on secure endpoints as required by

university policy. At no time was demographic data stored on the RPi. Data on the RPi computers

was protected by standard Linux login security. Theft was not considered a

significant threat, given the low value of the hardware and constant

surveillance of the space. Given these factors, it was determined that

accidental or malicious disclosure of collected data represented little to no

harm to participants in the study.

Experimental Setup

The library used two RPi

single-board computers and two RFID card readers compatible with the

University’s ID system. Both RPis were running the

latest build of Raspbian Linux available at the time. For the 2013 study, the

library used first generation model B RPis, which

lack Wi-Fi capability. Because the RPi has no

real-time clock, network connectivity (via wired Ethernet) was required for

accurate timekeeping. For the 2017 study, we used third generation RPis with built-in Wi-Fi connectivity.

One of the goals of this project was to minimize the

costs associated with technology and supplies.

The total bill of materials was just over $170 (see Appendix B for a

breakdown). We were able to use RFID card readers from our spare stock,

otherwise these would have cost approximately $160.00 each. The above hardware

would have sufficed for the 2017 rounds of data collection, but we elected to

update our hardware to gain Wi-Fi networking. For the 2017 project, we spent a

similar amount, less the cost of the foam core board.

The RFID card readers are USB human interface devices,

appearing to the RPis as a keyboard. When an ID card

is placed on the reader, it reads the card number and outputs it as a series of

digits, followed by the enter key (similar to an individual typing the number

and pressing enter).

One RPi was designated “IN” and the other was

designated “OUT” for collecting library entry and exit data, respectively. Both

RPis were configured to turn off the graphical

interface and to auto-login on the first virtual terminal (/dev/tty1) to the “cardstats” user, which ran a script, written in Perl, to

collect the 9-digit card number along with date and time each time a card was

read, and write it to local storage. If the script were to crash or exit, the

account would log out, and the auto-login process would re-start it.

The library produced a poster, printed on foam core board, with graphics

indicating which RFID reader was “IN,” which was “OUT,” and mounted the RFID

readers to the board with tape (Figure 1). In addition, the poster contained

information about the purpose of the project and how the collected card data

would be used (see Appendix A for the poster text). To maximize impact, the

library designed a reminder poster that could be seen easily as users entered

or exited the library.

Figure 1

Poster design for Tap In/Tap Out on one board.

The poster was placed on a tripod in a conspicuous location near the

entry of the library, near power, and, for the 2013 study, near Ethernet ports.

Each time the survey ran for just over two weeks, to allow 14 full days

of data collection. To protect against accidental data loss, card data was

copied daily to a secure location. During the 2013 study, staff used scp to retrieve the data daily. For the 2017 study, a

nightly job ran to copy the data to a Windows share via Samba.

Data Analysis

Data collected was saved in a tab-delimited, plain text file, with the

first column containing the card number, the second column an ISO 8601 date and

time statement, and the third column a directional indicator (IN or OUT). (See

Appendix C for an example of the raw data.) After collection, data was

transferred to a secure endpoint for further analysis.

For the 2013 study, data was analyzed using a custom Perl script

(Appendix D). During this study period, the library closed daily before

midnight. Therefore, any IN taps without a corresponding OUT tap at the end of

the day represented instances where the users had tapped in, but not tapped

out. (See Appendix C for an example of merged data.)

After collecting all card data, the list of card numbers was sent to an

analyst at Columbia University Information Technology (CUIT), who matched the

card numbers against the University’s ID Management database. CUIT returned the

list with added affiliation information, including role (student, faculty, or

staff), school, division, department, and academic program. (See Appendix C for example demographic

data.)

The 2017 study involved some adjustments to the data analysis process.

The change to the library’s hours to a 24-hour space required the ability to

compare data spanning two days. It was no longer possible to determine who had

left without tapping their ID as we did in the 2013 study. To resolve this

issue, we used a sliding six hour window based on the

tap in time to look for any exit taps. If no matching exit was found within the

six hour window, we assumed the user left the library

without tapping. We chose the six hour window based on

the duration of visit information from the 2013 study, where only one user

exceeded four hours in the library and none exceeded six hours.

Results/Outcomes

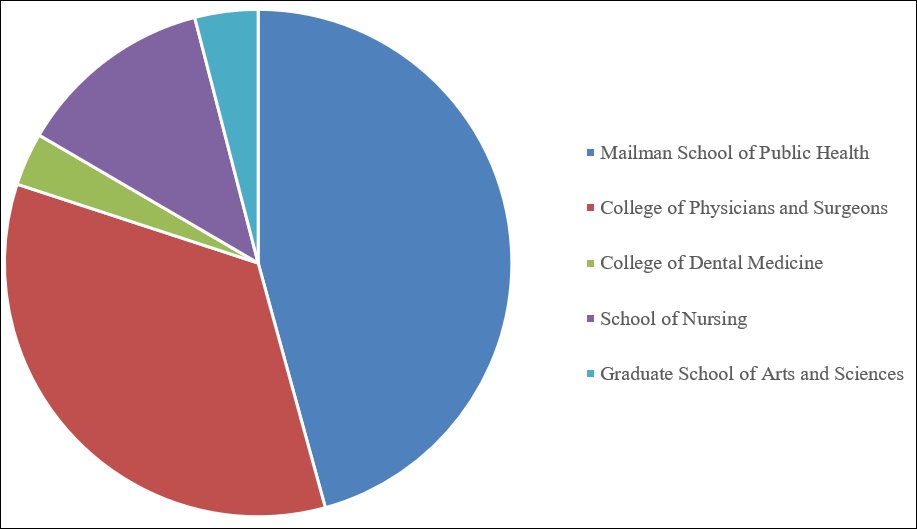

The primary use of the Tap In/Tap Out data has been to

quantitatively demonstrate to university administration the continuing value of

library space to the Medical Center community. The data strengthened the

library’s case for increased investment in library spaces. We found the two

most useful reports for administration to be a tabular count by department

(Appendix E) and a pie chart of library visits by school (Appendix F).

Response rates to the Tap In/Tap Out surveys were low

– 5% of the gate count in both 2013 surveys and the fall 2017 survey, 7% in the

spring 2017 survey – but provided a useful snapshot of patron demographics. The

response rate was calculated for each day in the study period and remained

within a 4% to 6.5% daily range. While we acknowledge that the information

collected was not representative of all library users, it was still useful for

management purposes to indicate usage and justify funding.

Results from the Tap surveys confirmed that the Health Sciences Library was

actively used by students from each of the four main CUIMC schools – the

College of Dental Medicine, Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health (MSPH),

School of Nursing, and College of Physicians & Surgeons (now Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, VP&S) – as

well as by the cross-campus students from the Graduate School of Arts and

Sciences and by students enrolled in programs at the university’s Morningside

Heights campus. The results also showed taps from faculty and staff. Since

there had been a perception that the library was only a student space, this was

useful hard data.

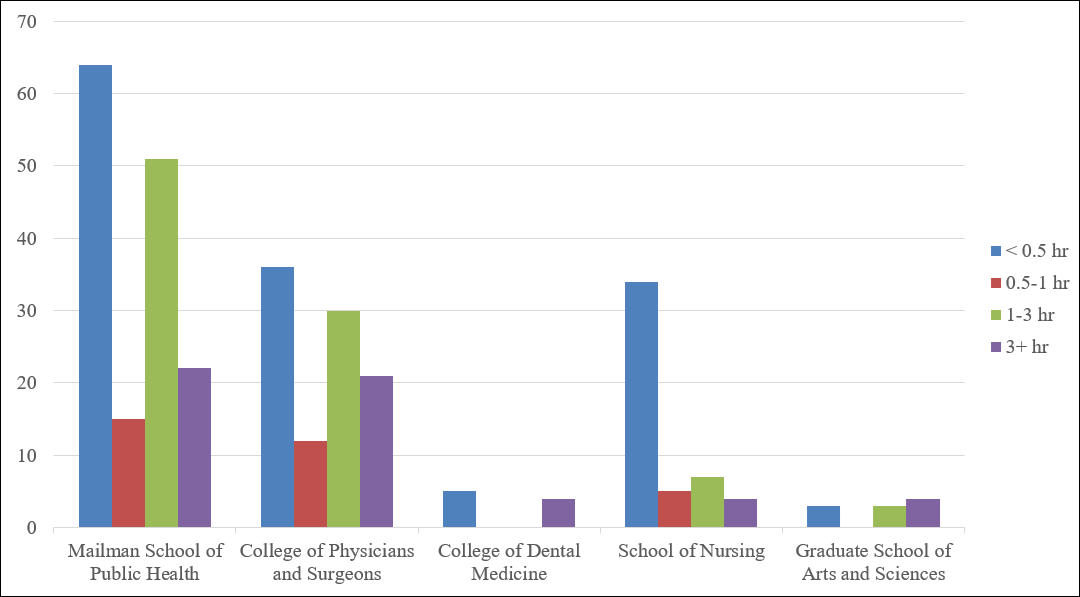

For those who tapped out, we were able to extrapolate the duration of

their stay. For the 2013 study, approximately two-thirds of taps recorded were

part of a matched pair, meaning we could determine the length of a user’s time

in the library. Analysis showed that 44% of respondents spent less than a

half-hour in the library during their visit. The second largest group (about

30%) were those who stayed for at least one and up to three hours. This data

supported anecdotal staff observations that a number of library users mainly

came to access a computer or printer, and then left shortly thereafter. But it

also showed that we also had users who spent more time in individual study or

on collaborative projects.

The 2013 study was used to determine the level of use from each of the

health sciences schools. We found that, in both the spring and fall semesters,

students from each of the CUIMC schools visited the library in roughly proportional

numbers in comparison to each school’s campus enrollment. The largest school by

enrollment, the Mailman School of Public Health (MSPH), were also the users who

tapped the most. The finding that MSPH users were the largest library user

population was a bit of a surprise. For many years, the working assumption had

been that the Vagelos College of Physicians &

Surgeons (VP&S) students were the largest library user population. In

addition, the duration data indicated that the space had to support both quick,

in-and-out uses such as printing, as well as extended study sessions.

At the time of the 2013 study, the library had started planning a major

renovation of its main reading room, but it had no source of funding for the

improvements. The demonstration that students from all of the CUIMC schools

used the library space allowed the library to tap into funding earmarked to

benefit students of all of the constituent schools. Recognition that MSPH

students were our largest community, along with knowledge that the MSPH

curriculum focused heavily on small group cooperation pointed toward the need

for spaces accommodating such groups. Finally, duration data led us to design

spaces suitable for both quick, in-and-out type visits, and for long study

sessions.

The 2017 study results were used to examine the extent of library use

(post-renovation) by students from each of the schools, as well as to compare

with the 2013 results to assess if our patron base had changed. Comparing the

same periods for both survey periods, one of the most significant findings was

that the VP&S students, one of our largest groups of users, had decreased

in the number of taps by 11 percentage points for the spring semester and 13

percentage points for the fall. This decrease was expected, as VP&S had

completed construction of a new medical education building in the interim, but

it was a welcome confirmation of the effect of this change and a reassurance

that the medical students had not completely abandoned the library, as was

feared.

Limitations

The primary limitation of the Tap In/Tap Out tool is that the data is a

self-selected sample. The study only captures a brief period of time and

participation is voluntary. Staff encouraged users to participate, but it was

observed that not all users swiped their IDs. As shown in the comparison of

taps with gate count, participation was low. To overcome this, more active

staff involvement in soliciting users to tap their IDs could help to increase

participation rates.

A second limitation is related to the concept of a “visit” to the

library. Users of the Health Sciences Library space will interrupt their study

time to access facilities outside of the library, such as restrooms and the

café. If users return immediately after leaving, is this one visit or two? The

correct answer to this question likely depends upon the intended case use for

the collected data. However, it is possible to process the data and screen for

an “OUT” tap followed closely by an “IN” tap so as to remove these brief exits

and re-entrances.

A third limitation is the requirements of the Raspberry Pi computer. As

a data collection device, the RPi performed admirably

for such an inexpensive device. As noted above, the lack of built-in Wi-Fi

capability in the first generation RPi dictated some

logistics of design and placement, which was resolved when we obtained a newer,

Wi-Fi capable, version of the RPi. The need for

electricity continues to constrain placement. In addition, as it is a general purpose computer, configuration requires staff with

knowledge of the Linux operating system and general programming that some

libraries may not possess. However, the Raspberry Pi online community includes

a wealth of helpful tutorials to configure and operate the computer. Academic institutions

with a computer science program could also potentially borrow the expertise of

students.

Conclusion

The Tap In/Tap Out tool met the design needs of the library

Our goal in creating the Tap In/Tap Out tool was to create a low-cost

method of collecting more details about the people using the library space. The

Tap In/Tap Out tool met our design needs because the Raspberry Pi computer

system and auxiliary items were low cost (under $200) and allowed us to gather

more demographic information on our users, such as their status, school

affiliation, and department. The tool was also voluntary and required little

interaction from library staff.

The Tap In/Tap Out tool allowed us to gather useful demographic data to

inform decision making

The data we collected with the Tap In/Tap Out tool helped to flesh out

the quantitative information we were collecting about library space use during

gate counts and to back-up or refute staff observations about space use. The

tool was a way to compensate for a lack of card-swipe entry gates and the

demographic detail those gates can provide. The Tap In/Tap Out tool allowed us

to gather similar demographic information about the users visiting the space,

such as their university affiliation, status, school, department, and/or

program. The 2013 and 2017 surveys were used to assess library space visits by

users from each of the Medical Center schools, make informed justifications for

library funding and renovation, and to help show that the library is a vital

element to the campus community.

The Tap In/Tap Out tool data was persuasive to university administration

The primary use of the Tap In/Tap Out data was to quantitatively

demonstrate to university administration the continuing value of library space

to the Medical Center community. The 2013 survey results helped to demonstrate

that students from all of the CUIMC schools used the library space. This

allowed the library to tap into funding earmarked to benefit students of all of

the constituent schools. The 2017 survey findings helped to demonstrate to

university administration that there was continued use by members from each

CUIMC school.

The Tap In/Tap Out tool is a possible option for other institutions

looking to gather more detailed user information

Institutions that want to know more than the number of people walking

through their doors, but who do not have the technological or financial means

to implement swipe-card entry gates, could use the Tap In/Tap Out tool as a

low-cost solution for gathering user information. As implemented, there are

some limitations due to the voluntary nature of participation, but more active

involvement by library staff in encouraging participation could overcome this.

Setting-up the tool is possible at most institutions, requiring only minimal

technical knowledge of the Linux operating system and a suitable programming

language.

References

American Library Association. (2002). Privacy: An

interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill/interpretations/privacy

Association of Research Libraries. (1976). User

statistics and studies. SPEC Flyer, 25, 1-2. Retrieved from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000689858

Cintron, J., Courtier, D., & DeLooper, J.

(2017). Testing three types of Raspberry Pi counters. Code{4}Lib

Journal, 38. Retrieved from https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12947

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research

methods in education. (6th ed.). Routledge.

Columbia University. (2012). Institutional Review Board standard operating procedures. Retrieved

from https://research.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/

HRPO/IRB_SOPSuperseded_v4.2_Nov2.12.pdf

Coombs, K. A. (2004). Walking a tightrope: Academic

libraries and privacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30(6),

493-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2004.08.003

Dotson, D. S., & Garris,

J. B. (2008). Counting more than the gate: Developing building use statistics

to create better facilities for today's academic library users. Library

Philosophy & Practice, 1-13. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/208

Jones, J. L. (2011). Using library swipe-card data to

inform decision making. Georgia Library Quarterly, 48(2), 11-13.

Retrieved from https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/univ_lib_facpres/21

Lux, V., Snyder, R. J., & Boff,

C. (2016). Why users come to the library: A case study of library and

non-library units. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(2),

109-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.01.004

Nackerud, S., Fransen, J., Peterson, K., & Mastel, K. (2013). Analyzing demographics: Assessing

library use across the institution. Portal, 13(2), 131-145. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0017

Sanders, M., & Hodges, C. (2014). An overnight success?: Usage patterns and demographics of academic

library patrons during the overnight period from 11 p.m.-8 a.m. Journal of Access Services, 11(4),

309-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2014.945121

Scarletto, E. A., Burhanna, K. J., & Richardson, E.

(2013). Wide awake at 4 AM: A study of late night user

behavior, perceptions and performance at an academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(5),

371-377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.02.006

Stewart, S. (2011). Building measurements: Assessing

success of the library’s changing physical space. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(6), 539-541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.09.002

Appendix A

Tap In/Tap Out Poster Text

Why Tap?

Q: Why is the library collecting data?

A: The library is collecting data to know more about

space use patterns.

Q: How is the library collecting data?

A: Library users should tap their ID cards when they

enter and exit the library.

Q: What data is the library collecting?

A: The library is collecting ID card number, time of

tap, and direction (“in” or “out”). CUIT

will look up card numbers and provide demographic information such as school

and department. The library will not

have access to personally identifiable information.

Q: How does this information help the library?

A: The library will be better able to understand who

is using the library, when, and for how long.

This understanding will inform space planning and future surveys.

For more information, please contact the Library at

[email protected]

Appendix B

The 2013 Tap In/Tap Out study bill of materials

|

Product |

Unit price ($) |

Quantity |

Total ($) |

|

Raspberry

Pi model B |

35.00 |

2 |

70.00 |

|

RPi case |

7.35 |

2 |

14.70 |

|

RPi power supply |

7.00 |

2 |

14.00 |

|

8GB

SD flash drive |

10.75 |

2 |

21.50 |

|

Printed

foam core mounting board |

50.00 |

1 |

50.00 |

|

TOTAL |

|

|

170.20 |

Appendix C

Sample of Data Collected

Sample of Raw Data

|

Card

Number |

Date/Time |

Direction |

|

XXXXXX365 |

2013-04-22T08:30:30 |

IN |

|

XXXXXX985 |

2013-04-22T08:33:10 |

IN |

|

XXXXXX121 |

2013-04-22T08:36:06 |

IN |

Sample of Merged Data

|

Card

Number |

Date/Time

IN |

Time

IN |

Date/Time

OUT |

Time

OUT |

Duration

of visit (minutes) |

Duration

of visit HH:MM:SS |

|

XXXXXX379 |

2013-04-25T08:37:16 |

8:37:16 |

2013-04-25T08:44:12 |

8:44:12 |

6.93 |

0:06:56 |

|

XXXXXX839 |

2013-04-25T09:06:00 |

9:06:00 |

2013-04-25T09:34:37 |

9:34:37 |

28.62 |

0:28:37 |

|

XXXXXX324 |

UNKNOWN |

UNKNOWN |

2013-04-25T09:39:40 |

9:39:40 |

UNKNOWN |

UNKNOWN |

|

XXXXXX991 |

2013-04-25T21:04:48 |

21:04:48 |

UNKNOWN |

UNKNOWN |

UNKNOWN |

UNKNOWN |

Sample of Demographic Data

|

SECURITY

ROLE |

ACAD

LEVEL |

SCHOOL

CODE |

SCHOOL

NAME |

DIV

CODE |

DIV

NAME |

ACAD

DEPT CODE |

ACAD

DEPT NAME |

PROG

CODE |

PROGRAM

NAME |

|

CUIMC FT Support Staff |

P |

SPUB |

THE JOSEPH L. MAILMAN

SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH |

PH |

PUB HEALTH |

HPM |

HEALTH POLICY

MANAGEMENT |

PMHPM |

HEALTH POLICY AND

MANAGEMENT |

|

CUIMC FT Student |

U |

SNUR |

SCHOOL OF NURSING |

RN |

NURSING-UGRD |

NURS |

SCHOOL OF NURSING |

RNETP |

COMBINED BS/MS PROGRAM

IN NURSING |

|

CUIMC FT Student |

P |

COPS |

COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS

AND SURGEONS |

PT |

PHYSCL THRPY |

PHYT |

PHYSICAL THERAPY |

PTDPT |

PHYSICAL THERAPY |

|

CUIMC FT Student |

G |

SNUR |

SCHOOL OF NURSING |

NP |

NURSING-GRAD |

NURS |

SCHOOL OF NURSING |

NPWOMH |

WOMEN'S HEALTH |

Appendix D

Perl Script

1)

Combine the IN and OUT files for each date.

2)

Sort the combined files for a single date in ascending

order by timestamp.

3)

For each IN record, save the card number and the time.

4)

For each OUT record, check previous INs

to see if there’s a corresponding entry.

a.

If yes, calculate duration of stay and output card

number, entry and exit times, and duration, write the result to file, and clear

the saved IN entry.

b.

If no, set IN time and duration to UNKNOWN and write

the result to file.

5)

At the end of processing, write out any unmatched IN

entries, setting OUT data and duration to UNKNOWN.

Appendix E

Count by Department

|

|

SUN |

MON |

TUE |

WED |

THU |

FRI |

SAT |

Total |

|

COLLEGE OF DENTAL MEDICINE |

|

|

7 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

21 |

|

COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS |

17 |

27 |

32 |

30 |

32 |

18 |

17 |

173 |

|

HUMAN NUTRITION |

|

5 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

|

16 |

|

MEDICINE |

10 |

14 |

15 |

14 |

17 |

11 |

11 |

92 |

|

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY |

1 |

|

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

5 |

|

PHYSICAL THERAPY |

6 |

8 |

15 |

12 |

12 |

1 |

6 |

60 |

|

COLUMBIA COLLEGE |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

16 |

|

SCHOOL OF CONTINUING EDUCATION |

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

SCHOOL OF GENERAL STUDIES |

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

SCHOOL OF NURSING |

4 |

9 |

21 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

58 |

|

THE FU FOUNDATION SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING &

APPLIED SCIENCE |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

THE JOSEPH L. MAILMAN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH |

15 |

46 |

41 |

47 |

36 |

23 |

11 |

219 |

|

BIOSTATISTICS DEPT |

2 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

|

7 |

|

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH SCIENCES |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

8 |

|

EPIDEMIOLOGY |

7 |

23 |

15 |

23 |

16 |

12 |

7 |

103 |

|

HEALTH POLICY MANAGEMENT |

2 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

36 |

|

POPULATION AND FAMILY HEALTH |

1 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

|

7 |

|

22 |

|

PUBLIC HEALTH |

|

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

|

7 |

|

SOCIOMEDICAL SCIENCES |

2 |

7 |

7 |

9 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

36 |

|

(blank) |

2 |

8 |

12 |

11 |

15 |

8 |

2 |

58 |

|

Grand Total |

39 |

94 |

117 |

107 |

98 |

59 |

38 |

552 |

|

Gate Count |

628 |

2425 |

2241 |

2344 |

1913 |

1428 |

572 |

11551 |

|

Response Rate |

6.2% |

3.9% |

5.2% |

4.6% |

5.1% |

4.1% |

6.6% |

4.8% |

Appendix F

Usage Charts

Usage Chart 1

Library Visitors by School -- Spring 2013 (based on a

2-week sample)

Usage Chart 2

Duration of Visit by School -- Spring 2013 (based on a

2-week sample)