Review Article

A Rapid Review

of the Reporting and Characteristics

of Instruments Measuring Satisfaction with Reference Service in Academic Libraries

Heidi Senior

Reference/Instruction

Librarian

Clark Library

University of Portland

Portland, Oregon, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Tori Ward

MLIS Graduate

Syracuse University

Syracuse, New York, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Received: 13 Feb. 2019 Accepted: 6 Nov. 2019

![]() 2019 Senior and Ward. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.

2019 Senior and Ward. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes,

and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the same or

similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29556

Abstract

Objective –

The objective of this review was to examine research instrument

characteristics, and to examine the validity and reliability of research

instruments developed by practicing librarians, which measure the construct of

patron satisfaction with academic library reference services. The authors were

also interested in the extent to which instruments could be reused.

Methods –

Authors searched three major library and information science databases: Library and Information Science

Technology Abstracts (LISTA); Library Science Database (LD); and Library

Literature & Information Science Index. Other databases searched were Current Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL);

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC); Google Scholar; PubMed; and Web

of Science. The authors identified studies of patron satisfaction with academic

library reference services in which the researcher(s) developed an instrument

to study the satisfaction construct. In this rapid-review study, the studies

were from 2015 and 2016 only. All

retrieved studies were examined for evidence of validity and

reliability as primary indicators of instrument quality, and data was extracted

for country of study, research

design, mode of reference service, data collection method, types of questions,

number of items related to satisfaction, and content of items representing the

satisfaction construct. Instrument reusability was also determined.

Results – At the end of the screening stage of the

review, a total of 29 instruments were examined. Nearly all studies were

quantitative or mixed quantitative/qualitative in design. Twenty-six (90%) of the studies

employed surveys alone to gather data. Twelve publications (41%) included a

discussion of any type of validity; five (17%) included discussion of any type

of reliability. Three articles (10%) demonstrated more than one type of

validity evidence. Nine articles (31%) included the instrument in full in an

appendix, and eight instruments (28%) were not appended but were described

adequately so as to be reusable.

Conclusions – This review identified a range of quality in librarians’ research

instruments for evaluating satisfaction with reference services. We encourage

librarians to perform similar reviews to locate the highest-quality instrument

on which to model their own, thereby increasing the rigor of Library and

Information Science (LIS) research in general. This study shows that even a

two-year rapid review is sufficient to locate a large quantity of research

instruments to assist librarians in developing instruments.

Introduction

Reference services are a

primary function of nearly every library. Library staff make themselves

available to patrons through multiple communication modes such as in-person,

chat, phone, and email in order to “recommend, interpret, evaluate, and/or use

information resources to help others to meet particular

information needs” (Reference and User Services Association, 2008). They

might gather statistics relating to the number and type of questions patrons

ask, and perhaps the difficulty of answering those questions according to the

READ Scale (Gerlich & Berard,

2007), but these statistics do not express whether patrons were satisfied with

the answer. To determine if their library’s patrons are satisfied with the

provided service, librarians need to obtain patrons’ opinions directly through

data gathering methods such as surveys or

interviews, known

collectively as research tools or instruments. They might then publish the

results of their study to help fellow librarians develop their own

patron-satisfaction tools. One study found that reference topics represented

9.5% of all library and information sciences research (Koufogiannakis,

Slater, & Crumley, 2004).

Systematic instrument review has been a common practice in health

science research and has developed to the extent that standards exist for

specific topic areas, such as the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection

of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) Initiative (2018). This type of

study uses systematic review methodology to identify and analyze the

psychometric characteristics of research instruments. While anthologies of

research instruments produced by librarians and measuring satisfaction with

reference services exist, such as those found in The Reference Assessment

Manual (American Library Association, Evaluation of Reference and Adult

Services Committee, 1995, pp. 255-345), to date it seems that no one has

published a systematic instrument review that would obtain an overall image of

the state of instrument development in this area. We therefore decided to

conduct a review to gain an understanding of the quality of instruments

produced by academic librarians studying patron satisfaction with reference

service.

Literature Review

While at the time of our study no reviews of instruments fully using the systematic review

methodology had appeared in LIS literature, we found that researchers had

mentioned instruments and evaluated them to varying extents in articles on

faculty attitudes toward open access publication (Otto, 2016); information

literacy (Beile, 2008; Schilling & Applegate,

2012); information seeking behavior (McKechnie, Chabot, Dalmer,

Julien, & Mabbott, 2016); satisfaction with chat

reference (Lasda Bergman & Holden, 2010); and

assessment of individual research consultations (Fournier & Sikora, 2015).

Of these researchers, only Lasda Bergman &

Holden (2010) followed a systematic review protocol in their research criteria

and search methods, retaining after their final appraisal stage 12 studies

regarding user satisfaction with electronic reference. However, because they

did not present details of each instrument in an evidence table, we were unable

to reproduce their data extraction process. Schilling and Applegate (2012)

identified 27 tools in their survey of academic library literature on student

learning assessment from 2007 to 2012 but did not take a systematic approach

and emphasized each instrument’s content rather than construction and

measurement concerns. Similarly, Fournier and Sikora’s 2015 scoping review

located 20 studies using various methods to assess individual research

consultations but did not review instrument characteristics beyond the type of

assessment method. Beile’s (2008) report covered

widely-known information literacy assessment tools that would provide data

“considered acceptable evidence for program reviews” (p. 1) such as

Standardized Assessment of Information Literacy Skills (SAILS) and Educational

Testing Service’s iSkills, but did not describe a

process for identifying the seven tests and four rubrics included in the paper.

McKechnie et al.’s approach to evaluating research rigor involved using a

checklist that asked whether authors attached or included their instrument – an

element we included in our study – and whether the instrument had undergone

pre-testing, an important component in demonstrating an instrument’s validity

(2016). While conducting a literature review prior to studying effective faculty

outreach messages regarding open access publication, Otto (2016) realized that

the studies reviewed did not accurately reflect faculty understanding due to

flaws in their underlying instruments such as failing to define terms, adapting

previous surveys without updating questions, and inserting inadvertent bias

into survey questions and response options. Although Otto did not report

evidence of the instruments’ validity and reliability specifically, several of

the issues Otto identified might have been resolved had the instruments’

developers paid closer attention to determining their validity.

Shortly before completing our manuscript, we learned

of the publication late in 2017 of a systematic review of 22 self-efficacy

scales assessing students’ information literacy skills (Mahmood) from 45

studies published between 1994 and 2015. Because Mahmood’s review was limited

to studies in which authors reported the use of any validity and also any

reliability indicators, it differs from our relatively unrestricted approach.

Mahmood’s study likely omits scales and does not provide a full picture of the

state of instrument development in this area.

We identified two instrument reviews from the field of

education (Gotch & French, 2014; Siddiq, Hatlevik, Olsen, Throndsen, &

Scherer, 2016), the second of which served as a preliminary model for the data

extraction stage of our pilot study. Gotch &

French (2014) reviewed 36 measures published between 1991 and 2012 of classroom

teachers’ assessment literacy, using “evaluation of the content of assessment

literacy measures beyond literature review and solicitation of feedback,”

“internal consistency reliability,” and “internal structure” to demonstrate

validity, and “score stability” (p. 15) to demonstrate reliability of each

instrument. We decided not to use Gotch and French as

a model because the authors did not rigorously follow a systematic approach in

database searching or in presenting their results in evidence tables. The

second systematic instrument review (Siddiq, et al., 2016) covered 38

information and communication technology instruments aimed at primary and

secondary school students, and was a useful framework to emulate because, like

our study, it was descriptive rather than evaluative in design. Furthermore,

the authors carefully documented their search strategy and findings in a way

that adhered closely to systematic review methodology. Like our study, the

authors appeared to be concerned to represent the state of the field and

included instruments whose developers did not address evidence of their

validity or reliability.

Our review of librarians’ studies examining

instruments determined that the instrument review methodology is under-used in

librarianship, and that our pilot study identifies a new area of research. By

drawing on similar reviews in education, we demonstrate the usefulness to

librarian-researchers of breaking out of disciplinary compartmentalization for

assistance with promising methodologies.

Research Questions

We began this study with a basic question:

What is the quality of research instruments produced

by librarians? We developed the following more specific questions using patron

satisfaction with reference services in academic libraries as a focus. We

defined reference service as librarians helping others to meet particular

information needs in-person at a desk, roaming, or via consultations; through

virtual methods such as chat and email; or over a telephone.

Q1: How did LIS researchers gather data on patron satisfaction with

academic library reference services in the years 2015-2016?

Q2: To what extent did the instrument developers document the validity

and reliability of their instruments?

Q3: To what extent are the instruments provided in an appendix or described in the publication, to

assist in reuse?

Method

Selection of Review Type

The systematic review is considered the most rigorous

methodology for gathering and synthesizing information based on predetermined

inclusion/exclusion criteria, clear and reproducible search methods, and

quality assessment, with results presented in an evidence table (Xu, Kang,

& Song, 2015; see also McKibbon, 2006; Phelps

& Campbell, 2012). Traditional systematic reviews, however, aim to be

comprehensive in coverage. Because the lead author wanted to accomplish as much

work as possible during a sabbatical, we elected to perform a rapid review,

which follows the systematic review methodology (predetermined

inclusion/exclusion criteria, clear and reproducible search methods, and

quality assessment, with results presented in an evidence table) but is limited

in time (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100). See Table 1 for distinctions between

systematic and rapid reviews.

Table 1

Differences Between Systematic and Rapid Review

Types

|

Review Type |

Description |

Search |

Appraisal |

Synthesis |

Analysis |

|

Rapid Review |

Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue,

by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing

research |

Completeness of

searching determined by time constraints |

Time-limited formal quality assessment |

Typically, narrative and tabular |

Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of

literature |

|

Systematic Review |

Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research

evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review |

Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching |

Quality assessment may

determine inclusion/exclusion |

Typically, narrative with tabular accompaniment |

What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty

around findings, recommendations for future research |

Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 95.

Inclusion Criteria

We assembled and agreed upon the following criteria:

- Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method

research studies measuring satisfaction with reference service carried out

in any type of academic library including health science libraries,

addressing any type of patron. We included studies measuring satisfaction

with several library services, as long as one question asked about

reference service.

- Studies published in 2015 or 2016

- Instruments developed by front-line librarians,

including adaptations of a standardized instrument such as SERVQUAL or

SERVPERF

- English, French, or Spanish language

Search Strategy

EBSCO’s Library and Information Science Technology Abstracts (LISTA) and

ProQuest’s Library Science Database (LD) were the primary sources of studies;

we also searched Library Literature & Information Science Index, CINAHL,

ERIC, Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science. In addition to these

databases, we searched the American Library Association, the Association of

College and Research Libraries, and assessment conference programs that were

published online for the years of interest.

When developing our search strategies, we kept in mind the caveat raised

by LIS authors that database thesauri might be incomplete or that subject

headings might not be applied uniformly. VanScoy and

Fontana noted in their 2016 study of reference and information service (RIS)

research that “This method relies on the RIS research articles being correctly

assigned the relevant descriptor in the databases” (p. 96). This warning echoes

that of McKechnie, Baker, Greenwood, & Julien in 2002 who said “Both [EBSCO

and ProQuest] indexes used terms … that were too general to be useful” (p. 123)

and found that indexing terms were incorrectly applied in 28-34% of the

articles they examined, as well as Greifeneder who

warned in 2014 that one of the studies in her literature review might have a

biased retrieval set because it included articles indexed under only two

subject terms rather than searching more widely (Background, para. 8). We

therefore decided to run both subject and keyword searches.

After a careful examination of subject terms used in either LISTA or LD,

and heeding past research on effective search strategy, we performed the

following searches:

LISTA: (academic AND librar* AND (reference OR

"user satisfaction")) AND (SU (research or surveys or questionnaires)

OR AB (study or survey* or interview* or research*))

LD: all ((academic* AND librar* AND (reference

OR "user satisfaction" OR "customer satisfaction" OR

"customer services"))) AND su(research or surveys or questionnaires) AND ab(study or

survey* or interview* or research*). Note that the LD search is identical to

the LISTA search except for the inclusion of “customer satisfaction” and

“customer services,” which are subject terms not used in the LISTA database.

Given the inconsistent application of subject terms in library

literature databases, we note that articles given the subject term “academic

libraries” might not describe undergraduate or community college libraries.

However, we found no additional articles when we re-ran searches with the

subject terms “community college libraries” and “undergraduate libraries.”

We then examined abstracts and developed a free-text keyword search that

we adapted for use in all of the databases, in an attempt to find all articles

that might not have had correct subject-term labels: (reference or "research

consultation") AND (satisf* or evaluat* or assess* or improve*) AND (experiment* or

survey* or qualitative or servqual or instrument or investigat* or analysis or questionnaire*) AND

"academic librar*". We also ran a broad

search for librar* AND reference AND satisfaction,

being mindful that the “academic libraries” label might not be uniformly

applied and that some articles might use “college” or “university” instead, or

that various labels might be used to represent different categories of library

patron, or different types of data-gathering instruments. We removed search

terms related to research methodologies to have broad retrieval.

Conforming to our inclusion criteria, we limited results in each

database to journal articles from the years 2015 and 2016 and checked each

database for conference papers as a separate source type. We did not apply

language or geographic location limiters and were prepared to examine articles

in French or Spanish in addition to English, but our searches retrieved only

English-language publications. In preparation for retrieving a large amount of

results, such as within Google Scholar, we determined that we would review the

first 300 items only. Within those 300 results, we ceased reviewing when we

began encountering irrelevant items.

When searching PubMed, we applied a search filter provided by COSMIN in

order to better identify all studies containing measurement properties. In Google Scholar, we utilized the Advanced

Search feature to narrow our results. In

ERIC and CINAHL, we utilized the database thesauri to identify subject terms. We

also hand searched 10 online journals (Journal of Academic Librarianship;

College & Research Libraries; Library & Information Science

Research; portal; Journal of the Medical Library Association;

Journal of Librarianship and Information Science; Reference Services

Review; Medical Reference Services Quarterly; Reference Librarian;

and College and Undergraduate Libraries), adhering to our year

restriction of 2015-2016. To standardize our searches, we created a table in

which both authors’ search strings were input to compare and ensure that we

were staying consistent with our searches and results.

All search strategies are provided in

Appendix A.

Reviewing Process and Study Evaluation

We compiled citations in a RefWorks database and removed duplicates

using the RefWorks tool. We examined bibliographic information from the

databases, such as title and abstract, to screen for relevant articles. To add

a peer reviewing element to our searches, we kept track of our subsequent

searches on a separate workbook so that each author could observe and be able

to discuss the quality of each search with the other. In those workbooks, we

documented the search conducted, the database in which the search was

conducted, the limiters set in each search, the results of each search, the

citations found from each search (if applicable), and any notes.

Data Extraction

As stated earlier, we used Siddiq et al.’s (2016) extraction sheet as a

model because we aimed to be descriptive rather than evaluative in scope. Following their model, we extracted

the following data: country of study; stated purpose of study; mode of

reference service; age/level of students (if students were part of the targeted

population); size of targeted population; usable responses; sampling strategy;

research design; data collection method; types of questions, other than

demographic (i.e., Likert scale format; presence of open-ended questions);

demographics gathered; technical aspects, such as distribution, availability of

translations, duration of survey period; time allotted to complete survey;

validity indicators; reliability indicators (see below for definitions of validity and reliability); instrument availability in appendix; reusability of

instrument, if not appended;

number of items related to satisfaction; content of items representing the

satisfaction construct.

Definitions

Generally speaking, an instrument is said to provide valid results when

it measures what the instrument’s developer intended it to measure within a

study’s setting and population, and reliable results when the instrument

provides the same score if repeatedly implemented among the same population.

Researchers have further specified various elements that assist in

demonstrating the validity of information obtained via an instrument. We used

these definitions when examining the instruments we gathered. Tables 2 and 3

include the codes we assigned to each element, to make our reporting table more

compact.

Table

2

Definitions

of Validity

|

Title |

Code |

Definition |

Evidence |

|

Face Validity |

V1 |

“The instrument appears to

measure what it claims to measure” (Gay, Mills, & Airasian,

2006 as quoted in Connaway & Radford, 2017, p.

82) |

Demonstrated through pre-testing,

ideally with subjects similar to the target population, and with instrument

development specialists |

|

Content Validity: Item |

V2a |

“…the items of the instrument or test …represent

measurement in the intended content area” (Connaway

& Radford, 2017, p. 81). |

Demonstrated through item analysis during

pre-testing |

|

Content Validity: Sampling |

V2b |

“…how well the instrument

samples the total content area” (Connaway &

Radford, 2017, pp. 81-82) |

Demonstrated through

discussion of included constructs |

|

Construct Validity |

V3 |

“…instrument measures the construct in question and

no other.” (Connaway & Radford, 2017, p. 83) |

Demonstrated through factor analysis, other tests of

dimensionality, to retain convergent (contributing) items and remove divergent

(non-contributing) ones |

|

Intercoder Reliability |

V4 |

Degree to which scorers or

raters agree on evaluating or observing a variable (Connaway

& Radford, 2017, p. 316). |

Demonstrated through

percentage agreement among raters |

We used these definitions

of reliability, and assigned these codes:

Table

3

Definitions

of Reliability

|

Title |

Code |

Definition |

Evidence |

|

Internal Consistency |

R1 |

How well items on a test

relate to each other. (Connaway & Radford, 2017, p. 84) |

Demonstrated through

Cronbach’s alpha, Kuder-Richardson 20 tests (Catalano, 2016, p. 8). |

|

Measurement Reliability |

R2 |

“The degree to which an instrument accurately and

consistently measures whatever it measures” (Connaway

& Radford, 2017, p. 83). |

Demonstrated through test-retest correlation,

meaning repeated administration to same group of the whole instrument

(Catalano, 2016, p. 8) or split-half method, meaning correlation of scores

obtained from each half of a tested population or from each half of an

instrument that measures a single construct (Catalano, p. 9; Connaway & Radford, pp. 83-84). |

We described an instrument as “resusable” only

when we could answer three questions about the instrument: Are the number of

questions reported? Is the full text of each question provided, and associated

items? Is the format of each question described: scale values, anchor labels

such as “Very Satisfied” and “Very Unsatisfied”? If we felt that we had to

guess as to whether the author fully described an instrument, we labeled it not

replicable. We automatically coded appended instruments as replicable. The most

frequent reason for describing an instrument as “not replicable” was that

authors did not supply the number of questions and items, so that we could not

be sure if they had described the entire instrument.

As explained earlier, we restricted the definitions of validity and

reliability to those used by Connaway and Radford

(2017), with occasional details borrowed from Catalano (2016). We decided not

to use the more expansive definitions that Siddiq et al. (2016) employed in

which for example an instrument’s having a basis in theory could be perceived

as evidence that it produced valid results. We developed our own evidence

extraction sheet to avoid obscuring the definition of each of these concepts:

we wanted to focus on precise definitions of validity and reliability, and

Siddiq et al.’s criteria extended beyond those definitions.

After completing the process of acquiring and screening studies, we

jointly read and reviewed six studies in duplicate and compared our extracted

data, to ensure that we agreed. We then separately reviewed the remaining 23

studies and consulted with each other on any confusing elements. After our

subsequent searches we divided responsibility similarly to review the nine

additional articles. When we disagreed, we located more information on the

issue to arrive at a consensus. For example, a disagreement about validity

types might require refreshing our understanding of the definitions. We did not

require a third party to resolve disagreements. We recorded our data in a

shared spreadsheet.

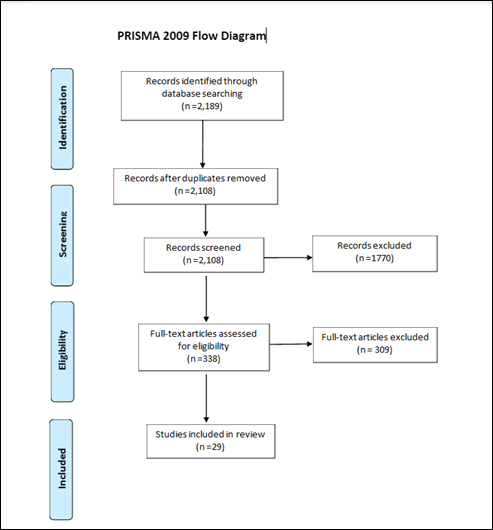

Figure 1

Flow chart of

review process

Results

Through our initial searches in seven databases, we found 2,189 articles

that appeared to be relevant to our study. After removing duplicates, we were

left with 2,108 relevant articles. We further reviewed the article titles and

abstracts and found that 1,770 were not truly relevant to our study. We

assessed the remaining 338 articles for eligibility and rejected 309 articles

because they described instruments measuring satisfaction with only the library

as a whole, or instruments measuring usage of or familiarity with reference

services, or instruments measuring satisfaction with services other than

reference. We extracted data from the final set of 29 studies. Figure 1 shows a

PRISMA flow chart of our process, a standard component of systematic review articles

(Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff,

& Altman, 2009).

We concluded during

the extraction process that certain criteria were more relevant to our

focus on the instrument development process and therefore decided not to report

irrelevant criteria such as “purpose of study,” “age of respondents,” “mode of service,” and “response

rate.” We excluded “time needed to complete the instrument” from this paper

because many authors did not report it. Additional criteria included article

title, journal, age/level of student, type of institution, sampling strategy,

technical aspects (e.g., distribution and survey period), and demographics

gathered. Although we gathered data in these categories, we found that these

criteria did not further our understanding of how librarian researchers report

on instrument development and implementation. Our evidence tables focus on the

following criteria: study; country; research design; data collection method;

types of questions; validity evidence; reliability indicators; whether the instrument

is appended; whether the instrument is mentioned in the abstract as appended;

and replicability of the instrument if

not appended. The list of extraction elements is in Appendix B, and the full

data extraction spreadsheet is available

online (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1M7MYhNcKbscrak9CqGpBg0X6z-d6V5qs-IwIE4I92SQ/edit#gid=0).

Outside of the data relating to our research questions, the data on

country of study might be of interest to researchers. Ten studies took place in

the United States of America; the second most common country was India with six

studies. The remaining studies took place in China (2), Ghana (1), Jamaica (1),

Malaysia (2), Nigeria (4), Philippines (1), and Taiwan (2).

These are the results of our data extraction as they relate to our

research questions:

Q1: How did LIS researchers gather data on patron satisfaction with

reference services in the years 2015-2016?

Of the 29 studies we gathered, 18 (62%) were solely quantitative in

design and one (3%) solely qualitative. We labeled ten (34%) studies as

combining both quantitative and qualitative designs, but this was usually

because we defined “mixed methods” broadly to allow open-ended questions to be

called qualitative; only two studies (7%) (Jacoby, Ward, Avery, & Marcyk, 2016; Verma & Parang, 2015) were truly mixed

using the more conservative approach as defined by Fidel (2008) in which

qualitative and quantitative methods were used to answer the same research

question. Askew (2015) and Yap and Cajes (2016)

employed quantitative methods to ask students about their satisfaction with

roaming reference service and qualitative methods to ask librarians about their

experience with providing the service; these studies are therefore labeled

“quantitative” for the purposes of this review.

Twenty-six (90%) of the studies employed surveys alone

to gather data. Construction of the surveys varied; the number of items related

to satisfaction ranged from 1 to 16. Eight (29%) of the studies asked only

about overall satisfaction with reference service, while another 10 (34%)

included an item about overall service

satisfaction as well as other attributes contributing

to satisfaction. Respondents were asked to consider aspects of librarian behaviour such as approachability and responsiveness,

helpfulness, respect for confidentiality, and offering referrals; and aspects

of librarian performance such as ability, accuracy, knowledge, and inspiring

confidence. Five instruments (Blake et al., 2016; Butler & Byrd, 2016;

Huang, Pu, Chen, & Chiu, 2015; Jacoby et al., 2016; Luo & Buer, 2015) asked students to gauge their likeliness to

use, re-use, or recommend the service. Masrek and

Gaskin reported presenting respondents with 10 items about Service quality,

usefulness, and satisfaction (p. 42) but unfortunately did not provide the full

text of the items within their article, making it impossible to determine how

they conceptualized these elements of satisfaction.

Researchers commonly used 5-point Likert scales to quantify respondents’

agreement or disagreement with statements; this type of scale occurred in 13

(45%) of the 29 survey instruments.

Three (10%) of these scales did not have the traditional neutral midpoint.

Two (7%) of the scales offered three positive scores versus two negative (Sivagnanam & Esmail, 2015; Xie & Sun, 2015); the third scale was recoded by its developers to have three negative scores and

two positive (Yan et al., 2015). Similarly, researchers employing 3-point

scales did not always include a midpoint; three studies (Butler & Byrd,

2016; Ekere, Omekwu, & Nwoha, 2016; Yap & Cajes,

2016) offered two positive options and one negative. Two 4-point scales

(Khobragade & Lihitkar, 2016; Yap & Cahes, 2016) were likewise unbalanced, with three positive

and one negative choices. Duan (2016) used 4-point

scales to measure satisfaction with different modes of reference service and

6-point scales to measure satisfaction with reference librarians’ behavior. The

remaining scales ranged in size from two scale points to nine.

Most authors used typical labels for scale points, e.g., variations on

“Very Satisfied,” “Somewhat Satisfied,” “Satisfied,” and “Very Dissatisfied,”

“Somewhat Dissatisfied,” and “Dissatisfied,” or related labels such as

“Useful,” and “Adequate,” but some authors labeled scale points differently

from these norms. Duan (2016) provided explanatory

text for each scale point, e.g., “Unsatisfied, because they solved few of my

problems but were not willing to help me again” (p. 164). Sivagnanam

and Esmail (2015) labeled their scale points “Not

Satisfied,” “Not Much Satisfied,” “Particularly Satisfied,” “Fairly Satisfied,”

“Absolutely Satisfied.” Yan, et al. (2015) were not clear, as it seemed they

gave their scale two midpoint labels, “Neutral” and “Not Familiar.” Most

5-point scales had a midpoint labeled “Neutral” (Askew, 2015; Blevins, et al.,

2016; Boyce, 2015; Huang et al, 2015; Mohindra &

Kumar, 2015) or “Neither Agree nor Disagree” (Jacoby et al., 2016; Masrek & Gaskin, 2016). Three authors did not report

the label used for their midpoint (Chen, 2016; Ganaie,

2016; Swoger & Hoffman, 2015).

A list of studies with their associated research design, data collection

method, and Likert-scale type is available in Table 4.

Table 4

Studies

Included in This Review

|

Study |

Research Design |

Data Collection Method |

Types of Questions |

|

Akor & Alhassan, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

4-point scale |

|

Askew, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Blake et al., 2016 |

Mixed |

Survey |

4-point scale, open-ended |

|

Blevins, DeBerg,

& Kiscaden, 2016 |

Mixed |

Survey |

5-point scale, open-ended |

|

Boyce, 2015 |

Mixed |

Survey |

Choose from list, 5-point scale, yes/no, open-ended |

|

Butler & Byrd, 2016 |

Mixed |

Survey |

3-point scale, open-ended |

|

Chen, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey (based on SERVQUAL) |

5-point scale |

|

Dahan, Taib, Zainudin, & Ismail, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey (based on LIBQUAL) |

9-point scale |

|

Duan, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

6-point and 4-point scales |

|

Ekere, Omekwu, & Nwoha, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

3-point scale |

|

Ganaie, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Huang, Pu, Chen, & Chiu, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Ikolo, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

2-point scale |

|

Jacoby, Ward, Avery, & Marcyk,

2016 |

Mixed |

Survey, Focus Groups, Interviews |

5-point scale; open-ended |

|

Khobragade & Lihitkar,

2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

4-point scale |

|

Kloda & Moore, 2016 |

Mixed |

Survey |

3-point scale, open-ended |

|

Luo & Buer, 2015 |

Mixed |

Survey |

5-point scale, open-ended |

|

Masrek & Gaskin, 2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Mohindra & Kumar, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Nicholas et al., 2015 |

Mixed |

Survey |

Choose from list, open-ended |

|

Sivagnanam & Esmail,

2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Swoger & Hoffman, 2015 |

Mixed |

Survey |

5-point scale, open-ended |

|

Tiemo & Ateboh,

2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

4-point scale |

|

Verma & Laltlanmawii,

2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

3-point scale |

|

Verma & Parang, 2015 |

Mixed |

Surveys, Interviews |

3-point scales |

|

Watts & Mahfood,

2015 |

Qual. |

Focus Groups |

Open-ended |

|

Xie & Sun, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Yan, Hu, & Hu, 2015 |

Quant. |

Survey |

5-point scale |

|

Yap & Cajes,

2016 |

Quant. |

Survey |

3-point and 4-point scales; another scale not specified |

Q2: To what extent are the instruments documented or included in the

body of a publication?

Nine articles (31%) included the instrument in full in an appendix, and

of the remaining studies we found that eight instruments (28% of the total) were replicable

according to our criteria as described earlier. Detailed information is

provided in Table 5.

We noticed that two of the instruments (Duan, 2016; Xie & Sun, 2015)

were translated into Chinese as well as English; both versions were available

to respondents, but the author described the English-language instrument within

the publication. We were unable to determine if any differences might exist

between the two versions.

Q3: To what extent are the instruments’ reliability

and validity documented?

Twelve publications (41%) included a discussion of any type of validity; five (17%) included discussion of any type

of reliability. Three articles (10%) demonstrated

more than one type of validity evidence. See Table 6 for a complete list.

Validity Evidence

Face Validity

Face validity was the most common type of validity represented, as nine

authors (31%) had pre-tested

their instruments; however, we found that in two cases (7%) (Akor & Alhassan, 2015; Blevins, DeBerg,

& Kiscaden, 2016) only librarian colleagues

participated rather than members of the target population or instrument

development specialists. The pre-testing process with potential respondents

varied; Blake et al. (2016) held campus interview sessions, while Butler and

Byrd (2016) informally polled library student employees. Kloda and Moore (2016)

and three sets of researchers (Askew, 2015; Huang et

al., 2015; Masrek & Gaskin, 2016) presented instrument

drafts to members of their respondent population. Only three studies (10%)

specifically reported pre-testing with a population contrasted with librarians

and therefore presumably instrument development specialists: Chen (2016) met

with “academic experts” (p. 319); Blake et al. worked with “experts from the

university’s Educational Innovation Institute” (p. 227), and Masrek and Gaskin (2016) pre-tested their instrument with

“experts in the faculty” (p. 42).

Table 5

Reusability of

Instruments Within Studies

|

Study |

Instrument Appended |

Reusability of Instrument |

|

Akor & Alhassan, 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Askew, 2015 |

No |

Yes |

|

Blake et al., 2016 |

Yes (Online) |

Yes |

|

Blevins, DeBerg,

& Kiscaden, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Boyce, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Butler & Byrd, 2016 |

Yes (Online) |

Yes |

|

Chen, 2016 |

No |

Yes |

|

Dahan, Taib, Zainudin,

& Ismail, 2016 |

No |

Yes |

|

Duan, 2016 |

No |

No |

|

Ekere, Omekwu, & Nwoha,

2016 |

No |

Yes |

|

Ganaie, 2016 |

No |

No |

|

Huang, Pu, Chen, & Chiu,

2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Ikolo, 2015 |

No |

Yes |

|

Jacoby, Ward, Avery, & Marcyk, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Khobragade & Lihitkar, 2016 |

No |

No |

|

Kloda & Moore, 2016 |

No |

Yes |

|

Luo & Buer,

2015 |

No |

Yes |

|

Masrek & Gaskin, 2016 |

No |

No |

|

Mohindra & Kumar, 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Nicholas et al., 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Sivagnanam & Esmail, 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Swoger & Hoffman, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Tiemo & Ateboh, 2016 |

No |

Yes |

|

Verma & Laltlanmawii,

2016 |

No |

No |

|

Verma & Parang, 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Watts & Mahfood,

2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Xie & Sun, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yan, Hu, & Hu, 2015 |

No |

No |

|

Yap & Cajes,

2016 |

No |

No |

Table

6

|

Study |

Validity Evidence |

Reliability Indicators |

|

Akor & Alhassan, 2015 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Askew, 2015 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Blake et al., 2016 |

V1, V2a, V3 |

Not stated |

|

Blevins, DeBerg,

& Kiscaden, 2016 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Boyce, 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Butler & Byrd, 2016 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Chen, 2016 |

V1 |

R1 |

|

Dahan, Taib, Zainudin, & Ismail, 2016 |

V3 |

R1 |

|

Duan, 2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Ekere, Omekwu, & Nwoha, 2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Ganaie, 2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Huang, Pu, Chen, & Chiu, 2015 |

V1, V3 |

R1 |

|

Ikolo, 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Jacoby, Ward, Avery, & Marcyk,

2016 |

V4 |

Not stated |

|

Khobragade & Lihitkar,

2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Kloda & Moore, 2016 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Luo & Buer, 2015 |

V2b |

Not stated |

|

Masrek & Gaskin, 2016 |

V1, V3 |

R1 |

|

Mohindra & Kumar, 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Nicholas et al., 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Sivagnanam & Esmail,

2015 |

V1 |

Not stated |

|

Swoger & Hoffman, 2015 |

c |

Not stated |

|

Tiemo & Ateboh,

2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Verma & Laltlanmawii,

2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Verma & Parang, 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Watts & Mahfood,

2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Xie & Sun, 2015 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

Yan, Hu, & Hu, 2015 |

V3 |

R1 |

|

Yap & Cajes, 2016 |

Not stated |

Not stated |

aV1 = Face validity; V2a = Content validity

(item); V2b = Content validity (sampling); V3 = Construct validity; V4 =

Intercoder reliability. See Table 2 for full definitions.

bR1 = Internal consistency. See Table 3 for

full definitions.

cIntercoder reliability coefficients not reported.

Content Validity: Item

Blake et al. (2016) were the sole authors to refer to

item validity as part of their instrument development process, borrowing the

definition from another paper by calling it “internal structure” (Downing,

2003, as cited in Blake et al., p. 227).

Content Validity: Sampling

Luo and Buer (2015) were the sole researchers

to address sampling validity; their instrument measured variables drawn from

the five areas outlined in the Reference and User Services Association’s (RUSA)

Guidelines for Behavioral Performance of

Reference and Information Service Providers, as well as from past research

on evaluation of reference service.

Construct Validity

Five publications (17%)

addressed construct validity as demonstrated by factor analysis and other tests

of dimensionality; three of these are described in the “multiple examples”

section below because they tested construct validity along with other forms of

validity. Two studies (7%)

addressed construct validity alone.

Yan et al. (2015) determined the value of average

variance extracted (AVE) to demonstrate convergent validity of the constructs

in their instrument, and reported that “all of the AVE values range from 0.6727

to 0.8019” (p. 562), and considered these values satisfactory citing Fornell and Larcker’s 1981

publication in which 0.5 is the threshold value for AVE. While not specifically

using the term “divergent validity,” Yan et al. demonstrated that they

identified divergent variables, stating that “Six variables ... are dropped due

to their relatively low factor loadings for its construct” (p. 562).

Dahan et al. (2016) used exploratory factor analysis, assessed using

Bartlett’s test for sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test, and determined

that the analysis was significant (p. 41). They then conducted Varimax testing

with the Kaiser Normalization Rotation method and found “that all Varimax

values are greater than 0.4 and therefore reflect the valid construct of all

items” (p. 41).

Intercoder Reliability

Of the ten mixed methods studies (34%), two authors (7%) presented

validity evidence in their reports in the form of inter-rater agreement on

thematic analysis. Two sets of researchers (Jacoby, Ward, Avery, & Marcyk, 2016; Swoger &

Hoffman, 2015) showed evidence of intercoder reliability, as they both

discussed and reviewed their coding process; however, they did not report

reliability coefficients.

Multiple Examples of Validity Evidence

Blake et al. (2016) provided evidence of face

validity, item validity, and construct validity within their study; Huang et

al. (2015) demonstrated testing for face validity and construct validity; and Masrek and Gaskin (2016) also showed evidence of a combination

of face validity and construct validity. Blake et al. changed their survey “to

reflect the responses received from librarian reviews and campus interview

sessions,” and consulted instrument development experts who helped them address

content (item) and internal structure (construct) validity components (p. 227).

Huang et al. invited 15 members of the college faculty to participate in their

pre-test, changing the wording of some items based on the faculty’s suggestions

(p. 1181), and tested for convergent and divergent validity using composite

validity and average variance extracted; they determined that convergent

validity was “good” and discriminant validity was “strong” (p. 1185). Masrek and Gaskin showed evidence of a combination of face

validity and construct validity as they pre-tested their instrument with

students who were part of the target population, as well as with experts in the

faculty, and as they analyzed the scales within their instrument for convergent

and discriminant validity (p. 44). We did not find evidence that any of these

researchers looked for convergent and discriminant validity with similar or

different instruments.

Reliability Indicators

Most (83%) of the studies did not state if they had

tested their instruments for reliability. Five articles (17%) (Chen, 2016; Dahan, et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2015; Masrek & Gaskin, 2016; Yan, et al., 2015) reported

measurement of internal consistency for each component of the satisfaction

construct when the component was measured by multiple scale items. All of the

researchers used Cronbach's ɑ (alpha) test of internal

consistency, in which a value of 0.70 is commonly believed to be a basic

threshold of acceptable level (Nunnally, 1978). Chen (2016) reported ɑ values ranging from 0.7305 to 0.8020, which represented a “satisfactory

level of reliability” (p. 322). Dahan et al. (2016)

reported alpha values ranging from 0.813 to 0.942 (p. 41). Values in Huang et

al.’s study (2015) ranged from .809 to .919 (p. 1184). Masrek

& Gaskin recorded ɑ “well above 0.7” (p. 42), with values ranging from

0.707 to 0.812. Yan, et al. (2015) did not report separate values for each

factor, stating that “Cronbach's alphas of all factors exceed 0.8” (p. 562).

Discussion

This rapid review

demonstrates that a less comprehensive

and time-consuming type of systematic review of measurement properties

can be a useful approach to gaining an overview of research by practicing

librarians, as well as pointing to areas for improvement. Our review confirms

some aspects of research studies that other librarian researchers have attended

to and identifies opportunities for further research. This discussion will

place our results within a broader context, followed by recommendations for

improvements in practicing librarians’ instrument design.

While solely quantitative study designs continue to be most common in

studies of satisfaction with reference services, approximately one-third of the

studies we located also gathered patron feedback via open-ended questions. For

comparison, VanScoy and Fontana determined in their

study of research approaches to reference and information service that

quantitative studies ranged from 56.65% in 2005 to 83.33% in 2009 (2016, p.

96). In our review, researchers used surveys alone to gather data 86% of the

time, which is higher than the usage of surveys by 50.5% of practitioner

researchers according to Hildreth and Aytac (2007) or

the 62.3% of researchers writing about library instruction, as determined by

Crawford and Feldt (2007, p. 84). However, our results are not surprising given

the quantitative design and measurement goal of the studies we identified. We

found an improvement over McKechnie et al.’s study in which 17.6% of articles

included an appended instrument (2016), with 31% providing this service.

Mahmood’s systematic review found that Likert scales “or Likert-type

scoring methods” were used in 15 of 22 scales, and that the “points for scoring

options ranged from 2 to 11” but did not report further detail about the design

of each Likert scale (p. 1044). It could be useful therefore to compare our

results regarding Likert-scale design with studies outside of LIS. Our partial

model for this study, Siddiq et al.’s systematic review of Information and

Communication Technology-literacy assessment instruments, did not include this

information, but Roth, Ogrin, and Schmitz (2016)

reported in their systematic instrument review that of seven instruments

containing Likert scales, three employed 4-point Likert scales, three contained

5-point scales, and two had 7-point scales. These findings indicate that little

agreement exists as to best practices in scale formation. Research on Likert

scale questions suggests that 4-point response scales with a “no opinion”

option avoid the 5-point scale’s potential for central tendency bias

(respondent desire to appear moderate rather than extreme) or social

desirability bias (respondent desire to avoid controversial topics). This

research implies that if a 5-point scale is offered, the midpoint should be

clearly labeled, as otherwise respondents might assign various meanings to the

midpoint such as “don’t know,” “neutral,” or “unsure” (Nadler, Weston, &

Voyles, 2015).

Librarian researchers might not adequately define “satisfaction,” as

only four researchers (14%) developed question items addressing more than one

aspect of this construct. Lasda Bergman and Holden

(2010) identified four components of the satisfaction construct: willingness to

return, positivity of experience, staff quality, and willingness to recommend a

service to a colleague. Luo and Buer’s instrument

(2015) included 10 components to express satisfaction but did not address

another potential component: ethical issues as identified by Kloda and Moore’s

(2016) question item, “The consult reflected a respect for my confidentiality

as a library user.” On their survey measuring satisfaction with digital library

service, including virtual reference, Masrek and

Gaskin (2016) included 24 items representing 6 component factors of

satisfaction, in addition to three items related to overall satisfaction (Masrek & Gaskin, personal communication, April 20,

2017). Instrument developers might consider that responses to a single question

about satisfaction are likely to be positive because “providing tailored

individual help … will always be appreciated, which skews user satisfaction in

survey results” (Fournier & Sikora, 2015, p. 255). When measuring multiple

aspects of the satisfaction construct, a researcher can determine which aspect most

likely detracts or adds to patron satisfaction, and initiate training, other

services, and environmental improvements to address any issues.

We were surprised to find that four of the studies we examined (Akor & Alhassan, 2015; Dahan

et al., 2016; Duan, 2016; Xie

& Sun, 2015) contained “double-barreled questions” (Olson, 2008, p. 210) or

“multi-concept” to use Glynn’s phrase (2006, p. 394), which asked respondents

to agree with statements containing two themes combined with “and” such as

“librarians are competent and helpful,” or to rate librarians’ “help and

answers.” Because the researcher doesn’t know which aspect of librarian service

respondents are rating – competence or helpfulness? help or answers? – these

items cannot contribute meaningfully to statistical analysis. Moreover,

respondents will likely take more time to consider each concept, potentially

leading to survey fatigue. Bassili and Scott (1996)

found that “questions took significantly longer to answer when they contained

two themes than when either of their themes was presented alone” (p. 394). If

researchers might design a survey instrument addressing the various components

that make up the satisfaction construct, and thus listing several items to

cover these components, it is important to make the items as simple to answer

as possible, to encourage respondents to complete the survey. Researchers will

usually catch multi-concept questions during a careful pre-testing process.

Half of the studies we located contained evidence of

instrument validity, while more than three-quarters did not report data on

instrument reliability, which is comparable to results from Mahmood’s (2017)

systematic review of instruments, and results from similar reviews in other

disciplines. While explaining that the study excluded articles without validity

or reliability evidence, Mahmood (2017) stated that “A large number of studies

reported surveys on assessing students’ self-efficacy in IL skills but without

mentioning any reliability and validity of scales” and that “the present

study’s results are consistent with systematic reviews in other areas,”

reporting that between 25% and 50% of studies in three systematic reviews

outside of librarianship included information on validity and reliability of

instruments (p. 1045):

For example, the reliability and validity were

reported in only one-third of studies about evaluation methods of continuing

medical education. . . . A study of 11 urbanicity

scales found that psychometric characteristics were not reported for eight

instruments. . . . A recent systematic review in the

area of assessing students’ communication skills found that less than half of

studies reported information on reliability and validity . . . (p. 1045).

Our model instrument review researchers Siddiq et al. found that 12 of

30 test developers (40%) reported validation of the test in at least one

publication, and that 24 of the 30 (80%) reported reliability evidence

according to the authors’ criteria (p. 75). The reporting of validity and

reliability evidence can help the reader determine which instrument to use in

replicating a study and could aid in future development of an instrument that

might combine constructs and items identified through a similar review.

Recommendations

Obtain Training and Refer to Research-Evaluation Checklists

Compared to classroom faculty, librarians are frequently at a

disadvantage in designing research projects because they lack coursework in

research methods. Initiatives such as Loyola Marymount University’s Institute

for Research Design in Librarianship, the Medical Library Association’s

Research Training Institute for Health Sciences Librarians, and occasional

professional development opportunities, assist librarians to build their

research knowledge but can’t reach every librarian. For these reasons, we

recommend that librarians become more familiar with existing checklists of

research evaluation (e.g., those provided by Glynn, 2006; and

McKechnie et al, 2016) that can ensure a basic level of structure and rigor,

and further recommend that researchers expand upon these lists as the need for

research guidance becomes apparent. Based on our study, we believe that

checklists for librarians need to include more guidance in instrument design

and in communicating instrument details, e.g., by making sure the target

construct is adequately measured; by addressing validity and reliability; by

designing questions and response items carefully; including the full

instrument; and citing prior instruments.

Completely Measure the Construct

When designing a research instrument, a researcher needs to determine

which construct to measure, and which items will best represent that construct,

whether it be satisfaction or any other construct. The researcher should keep

in mind that more specific items avoid the problem of confounding variables

which influence the respondent’s answer, or of misinterpretation in which the

respondent’s definition of a construct differs from the researcher’s intended

definition. In the realm of “satisfaction” with a service, many factors could

influence respondents’ opinion of the service being measured, such as librarian

behaviour or performance. It is therefore important

to offer several items, rather than a single question about satisfaction.

Address Validity and Reliability

After drafting questions and items, researchers will want to ensure

their instrument has face validity by pre-testing it, with non-librarian

subjects similar to the target respondent population and with experts in

instrument design. These pilot testers should look for bias, for example

avoiding questions such as “How much has this service improved your life?”

which assume a positive response; for clarity and avoiding the use of jargon,

defining terms as Otto (2016) recommended; and for evidence that the question

or item addresses what it is intended to address. If researchers try to address

all variables encompassing the “satisfaction” construct and report this effort

in their paper, that will show evidence of sampling validity. An instrument

with many items could be refined by performing analyses to determine convergent

and divergent items, thus demonstrating construct validity. If the instrument

has been translated into or from a language other than English, developers

should report separate validity and reliability information for each version of

the instrument.

Design Questions and Response Items Carefully

We repeat Glynn’s (2006) recommendation that not only questions but also

their “response possibilities” should be “posed clearly enough to be able to

elicit precise answers” (p. 389). Glynn cautions that the Likert scale (i.e.,

strongly agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, strongly disagree) “[lends itself]

to subjectivity and therefore the accuracy of the response is questionable” (p.

394). Regardless of the scale researchers select, we recommend

employing a 4-, 5-, or 7-point Likert scale. Avoiding 2-point scales allows for

variance in opinion, and avoiding 9-point scales or higher avoids dilution of

opinion. We further recommend that researchers label the scale points in a

uniform fashion but minimally, e.g., “Strongly/Somewhat/Agree” and

“Strongly/Somewhat/Disagree,” rather than offer lengthy definitions of each

point as seen in Duan(2016).

Include the Full Instrument

Several authorities on research (Connaway

& Radford, 2017; Glynn, 2006; McKechnie et al., 2016) also agree that, to

quote Glynn, “the data collection method must be described in such detail that

it can easily be replicated” (2006, p. 393). Ideally, these authors further

agree, researchers would include their instrument within the body or as an

appendix of their publication, or as an online appendix. We recommend expanding

existing checklists for the evaluation of research in librarianship, e.g.,

Glynn’s Critical Appraisal Tool for Library and Information Research (2006) and

McKechnie et al.’s Research Rigour Tactics (2016), to

remind authors that when they include an appendix containing the instrument,

they should also note its inclusion in their abstract, to increase the

likelihood that future researchers will locate it. If this inclusion is not

possible, then a detailed description of the instrument should be reported in

the body of the paper:

- The

number of questions and items

- The

full text of each question and associated item

- Question

format: scale range and endpoint labels, e.g., “Agree” and “Disagree”

- Where

relevant, the average time needed to complete the instrument

With this information in hand, researchers can readily reproduce the

instrument and use it in their own research.

Cite Prior Instruments

We recommend also that authors cite sources if they

base their instrument on previous efforts, demonstrating connections with prior

research and further helping to identify useful instruments. Blevins et al.

(2016) wrote that “three librarians reviewed the existing literature for

similar surveys and developed a set of questions to assess customer service

quality” (p. 287) but did not cite the similar surveys. By citing contributing

studies, librarians uphold the professional value of encouraging their

colleagues’ professional development as stated in the ALA Code of Ethics

(2008).

Further Research

As more librarians implement the instrument review methodology,

opportunities for future research will abound. Reviews are needed in other

research areas, for example to evaluate instruments gathering librarian

attitudes toward teaching, collection development, or collaborating with

faculty. While we have presented one model for this methodology, there is ample

room for improvement and refinement of the method; we foresee that specific

standards for instrument review could be developed for librarianship. As

described above, another opportunity for future research would be to examine

concerns of sampling validity, i.e., which items best demonstrate the patron

satisfaction construct.

Limitations

As a rapid review

examining two years of librarian research, this study’s results are not necessarily representative of the

body of work on student satisfaction with academic library reference services.

Although we ran keyword as well as subject searches, it is possible that we did

not gather all possible studies presenting librarian-developed instruments due

to inconsistent indexing. It is possible that we have missed relevant articles

due to not manually searching all LIS journals related to our research topic.

Our descriptive model does not extend to evaluation of

the instrument’s appropriateness in different scenarios such as in-house

research versus research intended for publication. While we generally recommend

designing an instrument that offers questions with several items measuring the

satisfaction construct, it could be appropriate to include a single question

and item addressing satisfaction when service quality assurance is the goal.

For example, Swoger and Hoffman (2015) incorporated a

single question about the usefulness of a specific

type of reference service; in their context the single

question was primarily used for local service evaluation and might have been

appropriate.

Conclusion

The quality of a research project depends on valid and reliable data

collection methods. In preparation for a study, librarians should search

broadly and attempt to locate the best instrument exemplars on which to model

their own data-gathering method. If researchers do not have time for a

comprehensive systematic review, the present study demonstrates that a rapid

review can reveal a range of research instruments and guide the development of

future instruments. It further demonstrates that the characteristics of

librarian-produced research instruments vary widely, and that the quality of

reporting varies as well. If librarians do not aim to produce high-quality data

collection methods, we need to question our collective findings. By following

the recommendations presented here, future researchers can build more robust

LIS literature.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Portland for granting

the lead author a sabbatical, during which much of the work of this study was

accomplished.

References

Akor, P. U., & Alhassan, J. A. (2015). Evaluation of reference services

in academic libraries: A comparative analysis of three universities in Nigeria.

Journal of Balkan Libraries Union, 3(1), 24-29.

American Library Association. Evaluation of Reference and Adult

Services Committee. (1995). The reference assessment manual. Ann Arbor,

MI: Pierian Press.

Askew, C. (2015). A mixed methods approach to

assessing roaming reference services. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 10(2), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8F60V

Bassili, J.

N., & Scott, B. S. (1996). Response latency as a signal

to question problems in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(3),

390–399. https://doi.org/10.1086/297760

Beile, P. (2008,

March). Information literacy assessment: A review of objective and interpretive

methods and their uses. Paper presented at the Society for Information

Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (SITE), Las Vegas, NV. Retrieved from http://eprints.rclis.org/15861/1/Info%20Lit%20Assessment.pdf

Blake, L., Ballance, D., Davies, K., Gaines, J. K.,

Mears, K., Shipman, P., . . . Burchfield, V. (2016). Patron perception and

utilization of an embedded librarian program. Journal of the Medical Library

Association: JMLA, 104(3), 226-230. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.008

Blevins, A. E., DeBerg, J.,

& Kiscaden, E. (2016). Assessment of service desk quality at an

academic health sciences library. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 35(3),

285-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2016.1189782

Boyce, C. M. (2015). Secret shopping as user

experience assessment tool. Public Services Quarterly, 11, 237-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2015.1084903

Butler, K., & Byrd, J. (2016). Research consultation

assessment: Perceptions of students and librarians. Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 42(1), 83-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.011

Catalano, A. J. (2016). Streamlining LIS research:

A compendium of tried and true tests, measurements, and other instruments.

Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Chen, Y. (2016). Applying the DEMATEL approach to identify the focus of

library service quality. The Electronic Library, 34(2), 315-331. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-08-2014-0134

Connaway, L. S., &

Radford, M. L. (2017). Research methods in library and information science

(6th. ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Crawford, G. A., & Feldt, J. (2007). An analysis of the literature

on instruction in academic libraries. Reference & User Services

Quarterly, 46(3), 77-87.

Dahan, S. M., Taib, M. Y., Zainudin,

N. M., & Ismail, F. (2016). Surveying users' perception of academic library

services quality: A case study in Universiti Malaysia

Pahang (UMP) library. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1), 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.006

Duan, X. (2016). How they search, how they feel, and how to serve them?

Information needs and seeking behaviors of Chinese students using academic

libraries. International Information & Library Review, 48(3),

157-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2016.1204179

Ekere, J. N., Omekwu, C. O., & Nwoha, C. M. (2016). Users’ perception of the facilities,

resources and services of the MTN Digital Library at the University of Nigeria,

Nsukka. Library Philosophy & Practice, 3815, 1-23.

Fidel, R. (2008). Are we there yet? Mixed methods research in library

and information science. Library & Information Science Research, 30(4),

265-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2008.04.001

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation

models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of

Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L. (2015). Individualized research

consultations in academic libraries: A scoping review of practice and

evaluation methods. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 10(4),

247-267. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZC7W

Ganaie, S. A. (2016). Satisfaction of library and information science students

with the services provided by Allama Iqbal Library of

Kashmir University. International Research: Journal of Library and

Information Science, 6(3), 504-512.

Gerlich, B. K., & Berard, G. L. (2007).

Introducing the READ Scale: Qualitative statistics for academic reference

services. Georgia Library Quarterly, 43(4),

7-13.

Glynn, L. (2006). A critical appraisal tool for

library and information research. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 387-399.

Gotch, C. M., &

French, B. F. (2014). A systematic review of assessment literacy measures.

Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 33(2), 14-18.

Grant, M., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of

reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91-108.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Greifeneder (2014). Trends in information behaviour

research. Paper presented at the Proceedings

of ISIC: The Information Behaviour Conference,

Leeds, England. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic13.html

Hildreth, C. R., & Aytac,

S. (2007). Recent library practitioner research: A methodological analysis and

critique. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 48(3),

236-258.

Huang, Y., Pu, Y., Chen, T., & Chiu, P. (2015).

Development and evaluation of the mobile library service system success model. The

Electronic Library, 33(6), 1174-1192.

Ikolo, V. E. (2015). Users satisfaction with library services: A case study

of Delta State University library. International Journal of Information and

Communication Technology Education, 11(2), 80-89.

Jacoby, J., Ward, D., Avery, S., & Marcyk, E. (2016). The value of chat reference services: A

pilot study. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(1), 109-129.

Jordan, J. L. (2015). Additional search strategies may

not be necessary for a rapid systematic review. Evidence Based Library &

Information Practice, 10(2), 150-152. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8FC77

Khobragade, A. D., & Lihitkar,

S. R. (2016). Evaluation of virtual reference service provided by

IIT libraries: A survey. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information

Technology, 36(1), 23-28.

Kloda, L.A., & Moore, A. J. (2016). Evaluating

reference consults in the academic library. In S. Baughman, S.Hiller,

K. Monroe, & A. Pappalardo (Eds.), Proceedings

of the 2016 Library Assessment Conference Building Effective, Sustainable,

Practical Assessment (pp. 626-633). Washington, DC: Association of

Research Libraries.

Koufogiannakis, D.

(2012). The state of systematic reviews in library and information studies.

Evidence Based Library & Information Practice, 7(2), 91-95.

Koufogiannakis, D., Slater, L., & Crumley, E. (2004). A content

analysis of librarianship research. Journal of Information Science, 30(3),

227-239.

Lasda Bergman, E. M., & Holden, I. I. (2010). User satisfaction with

electronic reference: A systematic review. Reference Services Review, 38(3),

493-509. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011084789

Luo, L., & Buer, V. B.

(2015). Reference service evaluation at an African academic library: The user

perspective. Library Review, 64(8/9), 552-566.

Mahmood, K. (2017). Reliability and validity of

self-efficacy scales assessing students’ information literacy skills.

Electronic Library, 35(5), 1035-1051. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-03-2016-0056

Masrek, M. N., &

Gaskin, J. E. (2016). Assessing users satisfaction

with web digital library: The case of Universiti Teknologi MARA. The International Journal of Information

and Learning Technology, 33(1), 36-56.

McKechnie, L. E., Baker, L., Greenwood, M., &

Julien, H. (2002). Research method trends in human information literature.

New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 3,

113-125.

McKechnie, L., Chabot, R.,

Dalmer, N., Julien, H., & Mabbott, C. (2016, September). Writing

and reading the results: The reporting of research rigour tactics in

information behaviour research as evident in the published proceedings of the

biennial ISIC conferences, 1996 – 2014. Paper presented at the ISIC: The