Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice

Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice

Research Article

Mixed Methods Not Mixed Messages: Improving LibGuides

with Student Usability Data

Nora Almeida

Instruction Librarian, Assistant Professor

Ursula Schwerin Library

New York City College of

Technology, City University of New York

Brooklyn, New York, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Junior Tidal

Web Services Librarian,

Associate Professor

Ursula Schwerin Library

New York City College of

Technology, City University of New York

Brooklyn, New York, United

States of America

Email: [email protected]

Received: 5 July 2017 Accepted: 23 Oct. 2017

2017 Almeida and Tidal. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Almeida and Tidal. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

– This

article describes a mixed methods usability study of research guides created

using the LibGuides 2.0 platform conducted in 2016 at an urban, public

university library. The goal of the study was to translate user design and

learning modality preferences into executable design principles, and ultimately

to improve the design and usage of LibGuides at the New York City College of

Technology Library.

Methods

– User-centred

design demands that stakeholders participate in each stage of an application’s

development and that assumptions about user design preferences are validated

through testing. Methods used for this usability study include: a task analysis

on paper prototypes with a think aloud protocol (TAP), an advanced scribbling

technique modeled on the work of Linek and Tochtermann (2015), and

semi-structured interviews. The authors introduce specifics of each protocol in

addition to data collection and analysis methods.

Results

– The

authors present quantitative and qualitative student feedback on navigation

layouts, terminology, and design elements and discuss concrete institutional

and technical measures they will take to implement best practices.

Additionally, the authors discuss students’ impressions of multimedia,

text-based, and interactive instructional content in relation to specific

research scenarios defined during the usability test.

Conclusion

– The

authors translate study findings into best practices that can be incorporated

into custom user-centric LibGuide templates and assets. The authors also

discuss relevant correlations between students’ learning modality preferences

and design feedback, and identify several areas that warrant further research.

The authors believe this study will spark a larger discussion about

relationships between instructional design, learning modalities, and research

guide use contexts.

Introduction

Subject

and course specific research guides created on the popular Springshare

platform, LibGuides, have become ubiquitous in academic library environments.

In spite of this, there has been little published research on the pedagogical

efficacy, use contexts, and design of research guides. The LibGuides platform,

which purports to be the “easiest to use web publishing and content creation

platform for libraries,” allows librarians to remix and reuse content across

guides and institutions, and caters to libraries who want a flexible tool for

curating library content that can accommodate librarians with little

technological literacy or experience with digital instructional design

(Springshare, 2017). However, just because librarians have subject expertise

and knowledge of specialized research practices does not necessarily mean they

can create digital resources that will be easy for students to use or that will

address the information needs students have in different contexts. As academic

libraries increasingly rely on digital platforms like LibGuides to reach

students conducting research off campus and to supplement or replace

face-to-face instruction, they should consider whether the subject and course

specific research guides they create reflect user preferences and research

behaviours. Librarians must also consider the various use contexts for online

research guides when making decisions about language, layout, navigation, and

interactivity.

This

article describes a mixed methods usability study the authors conducted in 2016

to learn more about student design preferences and learning styles, and to

improve subject specific research guides at the New York City College of

Technology’s Ursula Schwerin Library. The goal of the study was to translate

user design and learning modality preferences into executable design

principles. After introducing the project methodology and presenting study

findings, the authors will discuss discrepancies and study limitations, and

will outline several areas for future research. While focused on a specific

institutional context, the methodology and results of this study will be of

interest to librarians at other institutions who want to ensure that research

guides and other educational technology platforms deploy user-centric design

principles.

Institution and Platform Context

The

New York City College of Technology, colloquially known as City Tech, is one of

the City University of New York (CUNY) system’s 24 colleges. The campus is

located in downtown Brooklyn and is a commuter school primarily serving

residents of New York City’s five boroughs. Offering 2-year associate and

4-year baccalaureate programs, City Tech is known for technical and

professional programs such as nursing, hospitality management, and vision care

technology. The institution is demographically diverse and enrolls over 17,000

students. While the City Tech population is unique, enrollment trends and

student demographics reflect patterns at colleges and universities across the

United States (U.S. Department of Education, 2014).

LibGuides

is one of a number of educational platforms used by City Tech librarians for

information literacy instruction and outreach. LibGuides 2.0 was acquired

through a consortial CUNY-wide license and rolled out at the City Tech campus

in Fall 2015. The platform replaced previous research guides housed on

MediaWiki, the same open-source software that powers Wikipedia. Prior to the

2015 roll-out, a majority of faculty librarians at City Tech had no experience

creating guides on either the LibGuides 2.0 or 1.0 platforms. A project to

migrate existing MediaWiki guides to LibGuides 2.0 revealed that the guides

lacked consistency in terms of overall design, navigation, extent of content,

and interactivity. While the library employs user testing to inform the design

of the library website, subject expert librarians had autonomously developed

subject specific research guides without soliciting user feedback. The authors

realized that usability testing might provide insight into student preferences

and help improve the design of LibGuides while still giving subject expert

librarians the autonomy to curate disciplinary content.

Literature

Review

In

spite of its ubiquity, the LibGuides platform is currently underexplored in LIS

literature and some librarians have expressed concern that “there is sparse

research on how university students use LibGuides and what benefits it affords

them” (Bowen, 2014, p.152; Hicks, 2015; Thorngate & Hoden, 2017). Recently,

the LibGuides platform has received some critical attention from user

experience librarians but published case studies infrequently address

connections with regards to pedagogy, student learning modality preferences,

social dimensions of library technology, or sociocultural contexts of research

(Brumfield, 2010, p.64; Hicks, 2015). An exception to this is a forthcoming

study by Thorngate and Hoden (2017), who discuss the importance of “the

connection between research guide usability and student learning” and

explicitly connect design features with cognitive practices. The few existing

case studies that discuss LibGuides, user experience, and pedagogy point to the

necessity of qualitative and task based user testing approaches in order to

understand student learning styles, research behaviors, and design preferences

(Thorngate & Hoden, 2017; Bowen, 2014).

User Testing Protocols

Literature

on user testing protocols reveals that qualitative methods like interviews and

TAP can be combined with more traditional user experience protocols to generate

substantive, qualitative feedback. A mixed methods approach allows

experimenters to gain pointed feedback about specific design elements that can

then be analyzed alongside subjective learning modality preferences and user

behaviors (Linek & Tochtermann, 2015). The testing protocol initially

considered for the City Tech study included an A/B test combined with

semi-structured interviews in order to compare design variants and capture user

preferences for different layouts, page elements, and navigation schemas

(Young, 2014; Martin & Hanington, 2012). However, since A/B tests are most

effective with fully executed designs and a large number of study participants,

the authors concluded that paper prototyping was the most appropriate method

for testing interface variations using low-fidelity mock-ups (Nielsen, 2005).

Paper prototyping allows for an analysis of “realistic tasks” as study

participants “interac[t] with a paper version of the interface” (Snyder, 2003).

This protocol is flexible enough to be used with more than one interface

variation and, unlike A/B testing, only requires 5 participants to identify

most usability issues (Snyder, 2003; Nielsen, 2012). While some literature

indicates that users prefer computer prototypes in task based protocols, the

quantity and quality of feedback generated by paper versus computer prototype

testing is comparable (Sefelin, Tscheligi, & Giller, 2003; Tohidi, Buxton,

Baecker, & Sellen, 2006). Task analyses on paper prototypes are frequently

combined with TAP to capture subjective feedback and to identify “concrete

obstacles” participants encounter (Linek & Tochtermann, 2015). The TAP

protocol has been used for numerous usability studies involving LibGuides

(Thorngate & Hoden, 2017; Yoon, Dols, Hulscher, & Newberry, T., 2016; Sonsteby, A., & DeJonghe, 2013).

Numerous

usability studies have pointed to the “reluctance of people to express critique

and to verbalize negative thoughts during user testing” (Linek &

Tochtermann, 2015; Sonsteby & DeJonghe, 2013; Tohidi et al., 2006). To

invite more critical responses from study participants and to “receive more

informal, creative feedback,” experimenters can combine alternative methods

with traditional protocols and present “multiple alternative designs” to

participants (Linek & Tochtermann, 2015; Tohidi et al., 2006). One such

alternative protocol is the advanced scribbling technique, which can be

combined with traditional paper prototype task analyses and interviews. During

advanced scribbling, participants annotate paper prototypes with colored

highlighters in order to identify important, confusing, and unnecessary design

elements (Linek & Tochtermann, 2015).

Linek and Tochtermann (2015) describe this protocol as a “systematic way

of receiving feedback and avoiding ambiguity” and also note this method may

reduce barriers to critique because it “enables the evaluation of single design

elements without pressuring the participant to express explicitly negative

comments.”

LibGuide Templates and Design Elements

Libraries

cite user studies, case studies, or best practices documentation on the

Springshare LibGuides website as the basis for local design decisions (Bowen,

2014; DeSimio & Chrisagis, 2014; Dumuhosky, Rath, & Wierzbowski, 2015;

Duncan, Lucky, & McClean, 2015; Thorngate & Hoden, 2017). However, it

is important to note that many institutions use LibGuides without conducting

any user testing or surveying published case studies to inform design. As a

result, many LibGuides are problematically “library-centric” in terms of how

information is presented and organized (Hicks, 2015). Hicks (2015) argues that

such unreflective design practices can undercut critical pedagogical models and

“marginalize the student voice from the very academic conversations” that most

concern them. Consequently, user testing is not only important in terms of

defining design decisions but may also be a critical imperative if such

interactions yield important insights into how students learn.

LibGuides

are most successful if they focus on student information needs and reflect

student research behaviors. Researchers have found that students will abandon

guides if they are confusing, cluttered, or if the purpose of the guide is not

immediate apparent (Gimenez, Grimm, & Parker, 2015). Some institutions have

opted to replace librarian-centric terms such as “articles and journals” with natural

language terms such as “magazines” or “news” after conducting user testing

(Sonsteby & DeJonghe, 2013). Additionally, several studies specifically

looked at how students respond to the use of columns on LibGuides and

introduced strategies to reduce “noise” and clutter (Gimenez et al., 2015;

Thorngate & Hoden, 2017).

Many

libraries make use of LibGuides templates to hard code design elements and

ensure design consistency across research guides (Duncan, Lucky, & McClean,

2015). Templates not only make guides more useful to students but also allow

subject selectors to focus on content instead of technical aspects of the

LibGuides platform (Duncan et al., 2015). While specific template

recommendations are helpful in that they identify concrete design elements on

the LibGuides platform, it is essential that libraries consider specific user

populations, institutional cultures, and use contexts when designing LibGuide

templates.

Aims

The

primary objective of this mixed methods user study was to understand City Tech

students’ design and learning modality preferences and to improve subject

specific research guides. The study was designed to capture students’

impressions of multimedia content such as videos, images, embedded

presentations, text-based content, and interactive instructional content like

search boxes or quizzes. This was in the context of a specific research

scenario and in relation to a specific platform interface. The authors used

study findings to document best practices for design, and plan to translate

this document into a new hard-coded LibGuides template that includes a standard

navigational schema and layout. For optimal features that may not be relevant

for every guide or subject area, the authors plan to create a series of custom

LibGuides assets that librarians without technological expertise can easily

pull into research guides.

Methodology

Before

beginning user testing, the authors worked with an instructional design intern

to conduct a brief content audit of the subject specific guides migrated from

MediaWiki. This audit revealed that some guide content was out of date, content

was duplicated, most guides were heavily text-based, the migrated guides used

inconsistent database linking protocols, and most guides did not have embedded

search opportunities or interactive features. In the Fall 2016 semester

database assets were loaded into LibGuides in order to resolve linking issues.

A handful of guides were revised to mitigate duplication and to remove some out

of date content before user testing began.

After

conducting a literature review, the authors determined that a mixed methods

approach would yield the most robust data about student design and learning

modality preferences. The methods ultimately used for the study included a

combination of paper prototyping, advanced scribbling, task analysis, TAP, and

semi-structured interviews. Below, each protocol is described along with how

data was compiled and analyzed. After refining the project methodology, the

authors worked with the instructional design intern to develop two paper

prototypes: a control prototype that mirrored a typical subject guide, and a

revised prototype that used a simplified navigation schema and included more

multimedia elements. Ten student participants were recruited through flyers and

email blasts, and were compensated $5.00 for 30 minute individual test

sessions. The authors and the instructional design intern conducted testing in

December 2016 with one experimenter serving as proctor, a second experimenter

as note taker, and a third experimenter as a human “web server” who supplied

access to interior pages of the prototype after study participants “clicked” on

features or menu items during the task analysis phase. Results were analyzed

and shared with the City Tech Library department in Spring 2017 and the authors

plan to complete the template and library faculty training in Fall 2017.

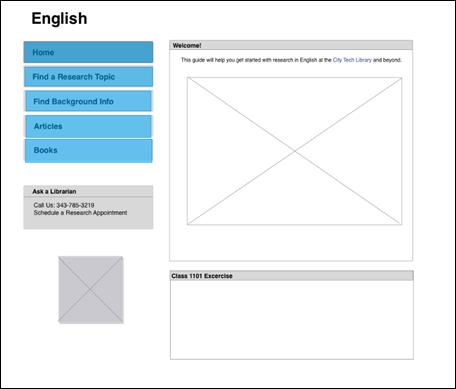

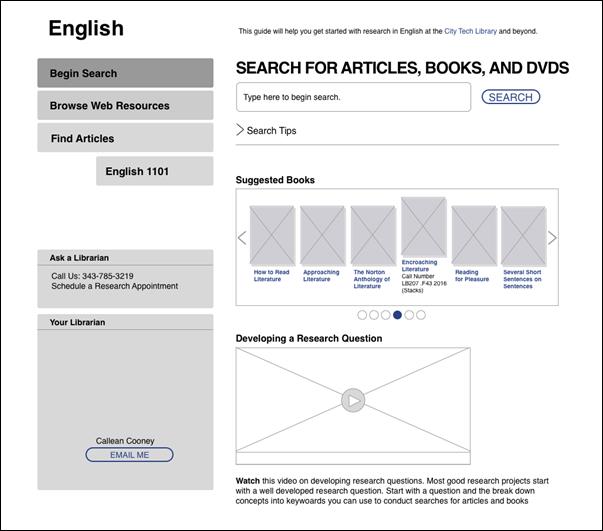

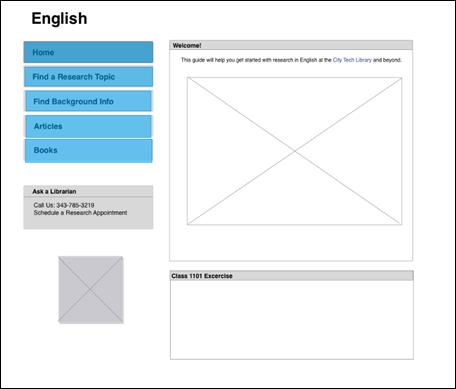

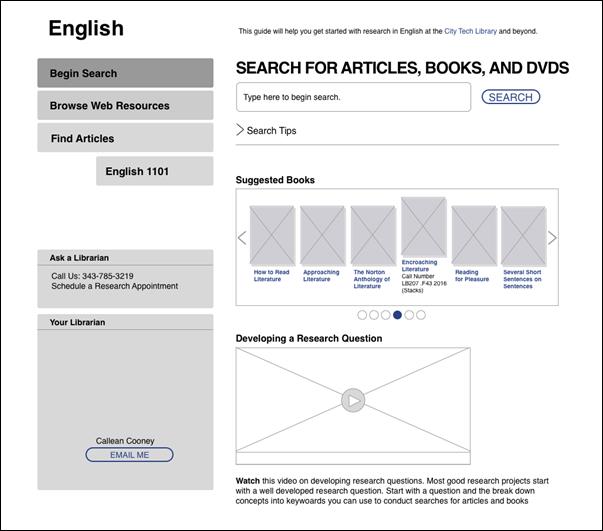

Paper Prototyping

Student

participants were given two paper prototypes emulating two variations of the

landing page of an English research guide. The control prototype had a

two-tiered primary navigation menu, a static welcome image, and contained few

linked elements with the exception of a list of recommended databases.

Alternatively, the revised prototype contained a minimal primary navigation

menu with labels containing action verbs like “find” or “search”, introduced

more opportunities for interaction with search boxes and collapsible info

boxes, and contained multimedia features including a book gallery and video

(see Appendix B and C). Participants were asked to annotate

both prototypes following the advanced scribbling protocol guidelines (see

below). Subsequently, participants selected their preferred layout, answered

questions about their modality and design preferences in a semi-structured

interview (see below), and completed a research task on the paper prototype

that they selected (see below).

Advanced Scribbling

Participants

were given green, yellow, and red highlighters and instructed to color code

design elements on both the control and revised prototypes. Students marked

elements they deemed important in green, confusing in yellow, and unnecessary

in red and used a pen for substantive annotations. Data for advanced scribbling

was collected by tabulating how users color coded each design element on each

prototype. Since not all participants marked every element, percentages of

elements coded as important, confusing, and unnecessary on the two prototypes

were calculated by assessing the color coded elements in relation to the total

number of participants who marked that element.

Interviews

Prior

to scribbling, participants were asked contextual questions about their

learning preferences and research experience (see Appendix A). After completing the advanced scribbling task on both

prototypes, students were asked questions about the prototypes including which

interface they preferred and why. Students were asked to expound upon their

scribbles and to provide feedback on the navigation labels and the extent of

content displayed on each guide. During these semi-structured interviews, a

note taker recorded student feedback. Responses were tabulated for yes / no and

either / or questions. During the data analysis phase, the authors identified

keywords and mapped thematic patterns for qualitative feedback that could not

be easily tabulated. For example, in response to the question “have you used

the library to conduct research?” many students mentioned that they had

borrowed books or used library databases or articles. The authors identified

books, databases, and articles as keywords and were thus able to identify

patterns about the types of research materials study participants had

previously used.

Task Analysis and TAP

After

the interviews, participants were given two hypothetical research scenarios

(see Table 2 below) to test how well the prototype interfaces supported the completion

of these tasks. During the task scenarios, participants were told to

“think-aloud,” verbally expressing their thought processes. Metrics were

recorded for each task scenario, including fail/success rate and the number of

“clicks” that users would need to complete the task. TAP response data was

combined and analyzed with qualitative interview feedback using keyword

analysis and thematic mapping.

Findings

Participant Profiles

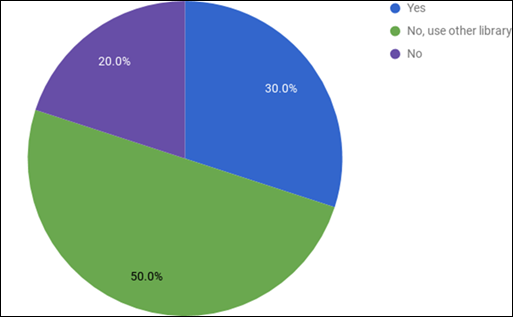

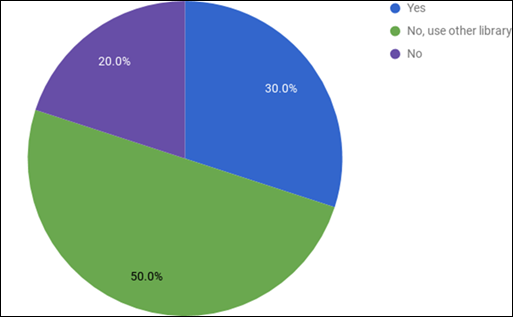

Most

student study participants indicated that they had some experience in academic

research environments. Participants characterized themselves as either beginner

or intermediate level researchers. The majority of participants (50%) indicated

they regularly used a library other than the City Tech Library, 20% were not

library users, and the remaining 30% of participants were City Tech Library

users (see Figure 1). Only 4 out of 10 participants had ever attended a library

instruction session. None of the participants in this study had previously used

an online library research guide.

Figure

1

Participant interview responses about library usage.

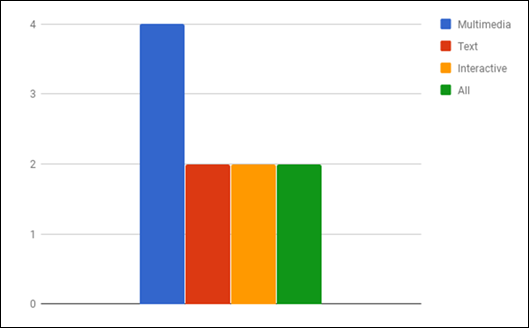

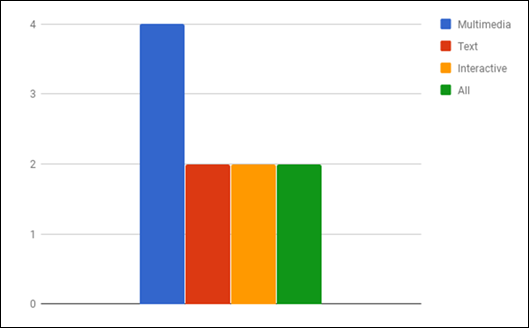

Figure

2

Participants’ preferred types of content.

During

interviews, student participants expressed a slight preference for multimedia

over text-based content, interactive content, and the combination of all types

of content (see Figure 2). Student media

preferences were corroborated by analysis of advanced scribbling protocols and

qualitative feedback compiled during user testing.

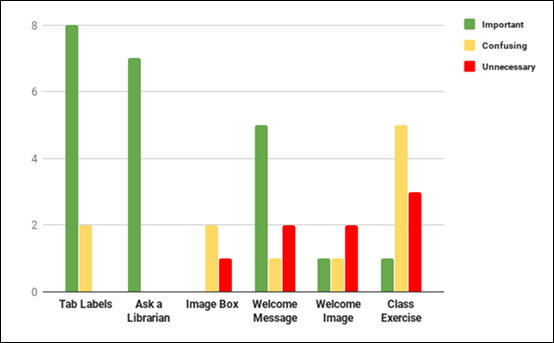

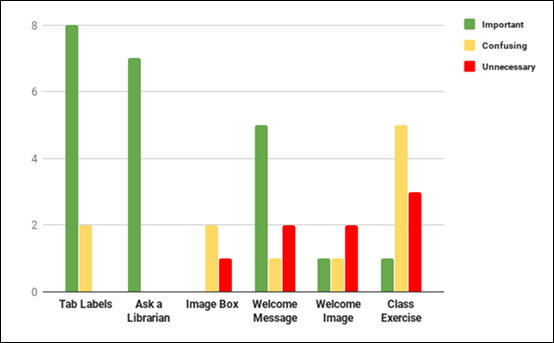

Figure 3

Participants’ advanced scribbling data for paper Prototype A.

Design Elements

Fifty

percent of study participants preferred the control prototype (Prototype A) and

50% of users preferred the revised prototype (Prototype B). Since no best

overall design emerged from this study, the authors will highlight specific

feedback on individual design elements across both prototypes in their

analysis. The advanced scribbling protocol yielded some contradictory data with

some students marking elements as important and others marking those same

elements as either confusing or unnecessary. Some contradictory data is the

result of variations in student design or modality preferences, and other

disparities were clarified in semi-structured interviews.

The

highest ranking elements (see Figure 3) of the control prototype (Prototype A)

were the primary navigation menu, the “Ask a Librarian” box, and the welcome

message providing context for the guide. A large majority of users marked the

class exercise element as either unnecessary or confusing, and three users

indicated that the welcome image was confusing or unnecessary.

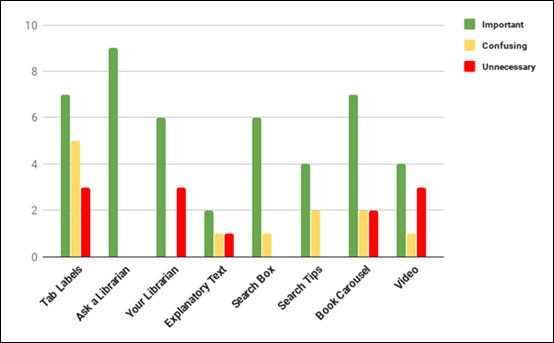

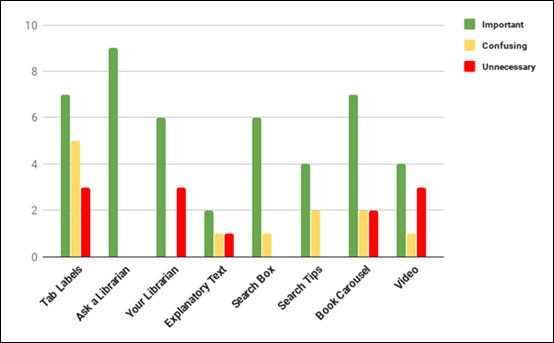

There

was less clear consensus about design elements on the revised prototype

(Prototype B), although several elements received positive rankings from users

(see Figure 4). High ranking elements included the primary navigation menu,

although seven out of ten users found specific tab labels within the main menu

confusing or unnecessary. While qualitative feedback suggested that language

was important to users, none of the student participants provided feedback on

the use of action verbs versus nouns in labels (e.g. “Find Articles” vs.

“Articles”). Other high ranking elements on Prototype B were the book carousel,

the search box, and the “Ask a Librarian” box. Several elements received mixed

rankings including an instructional video which four users marked as important

but three users found unnecessary, perhaps reflecting variations in modality

preferences. The “Your Librarian” box

Figure

4

Participant advanced scribbling data for paper Prototype B.

Table

1

User Feedback About Template Elements

|

"Begin

Search" should be "Home"

|

|

There

are two "Search"

|

|

"should

not be 2 search options"

|

|

Ask

a librarian + contact [your librarian] are redundant

|

|

Combine

"ask a librarian" and "your librarian" boxes

|

was

ranked as important by six users, but three marked this feature as unnecessary,

and qualitative feedback revealed that some students found this feature

redundant.

Qualitative feedback

In

interview questions and during the TAP, users offered some concrete suggestions

for the guide layout and navigation labels that could be incorporated into the

LibGuides template (see Table 1). Several users pointed out redundant features

that should be consolidated, including the “Ask a Librarian” and “Your

Librarian” boxes, and the search box widget and the “Begin Search” menu item on

Prototype B. Participants also noted that the purpose of the guide should be

explicit and they wanted to be able to conduct research without navigating away

from the guide or being redirected to the library website.

Table 2

Tasks That Users Were Asked to Attempt on the Paper Prototypes

|

Task 1:

Where would you go on this guide to find scholarly articles?

|

|

Task 2:

Where would you go on this guide to search for books in the City Tech

library’s collection?

|

Task Analysis

Participants

were given a hypothetical research scenario during which they were asked to

conduct scholarly research for a paper on post-colonial Caribbean literature.

Students were then given two tasks to complete on their preferred prototype in

relation to the scenario (see Table 2).

Task

completion success rates were high (above 80%) on both prototypes with a

slightly higher failure rate for Prototype A. The lack of a search box on

Prototype A accounted for most failures since users would have to navigate away

from the guide to search the library’s electronic and print holdings.

Additionally, several participants had difficulty interpreting certain elements

on the paper prototypes and in some cases assumed that certain features were

hyperlinked. This resulted in a small percentage of false positives where users

incorrectly believed they had successfully completed a task. This data was

useful in that it revealed student expectations for linked and dynamic

elements.

Navigation

The other metric recorded during the task analysis phase was the number of

“clicks” needed to complete each task. A click was recorded whenever a

participant indicated they would use the search box, follow a link, or go back

a page. The click averages were low for both prototypes and tasks, with less

than three clicks performed by all users per task. Click averages for task two

were substantially lower for both prototypes. The authors speculate that this

is a result of learnability as users became

more

comfortable with the prototype layouts after completing task one.

Discussion

Implications for Design

No

“best” layout emerged as a result of the usability study and thus, the authors

will focus on design elements ranked favorably across prototypes in developing

a new user-centric template. Based on participant feedback, the authors plan to

maintain the labels and navigation schema used in Prototype A but will

incorporate more multimedia and interactive content to ensure LibGuides can

accommodate different learning modality preferences. Study findings indicate

that students should be able to complete basic research tasks from within

research guides, and a search widget for the City Tech Library’s discovery

layer will be hardcoded into the final template. Based on user suggestions, the

“Your Librarian” and “Ask a Librarian” boxes will be combined. Since there was

some ambiguous feedback on multimedia features, the video and book carousel

elements will be made available as optional assets that can be integrated into

guides where appropriate.

In

addition to producing a new template and multimedia assets, the authors plan to

provide training for City Tech librarians and to discuss strategies to use

LibGuides as part of the library’s instruction program. While creating a

standardized template and faculty librarian training can make research guides

more intuitive and easy to use, guides must be analyzed in relation to one-shot

instruction sessions and reference desk interactions to ensure they align with

pedagogical models. Defining concrete usage contexts for guides will help City

Tech librarians tailor guides to meet student needs and help ensure that

digital tools enhance information literacy outcomes.

Learning Modalities, Research Experience, and

Design Correlation Analysis

This

study revealed a positive correlation between learning modality and design

preferences. Students who selected Prototype B were more likely to indicate

that they favour multimedia as their preferred learning modality during the interview

phase of the study, and were more likely to mark interactive and multimedia

elements as “important” during the advanced scribbling protocol phase (see

Figures 3 and 4, above). Students who selected Prototype A were more likely to

indicate that they learn best by reading, and were more likely to mark

text-based contextual elements as “important” during the advanced scribbling

protocol.

The

authors found no comparable correlation between participants’ level of research

experience and design preferences but believe a larger sample size and more

diverse participant pool may be needed to measure whether research experience

is predictive of design preference. If such a correlation were found, librarians

could more effectively customize guides for different research levels.

Disparities and Study Limitations

While

analyzing the study data, the authors identified some disparities and study

protocol limitations. In some cases, student participants had difficulty

reading design cues on the low-fidelity mock-ups, which is a known limitation

of paper prototypes (Sefelin, et. al., 2003). In particular, users were

confused about image placeholders and assumed that certain static elements were

hyperlinked. These limitations did not significantly skew data because of the

mixed methods approach but may have impacted overall preferences for one

prototype over another. Disparities arose in instances where individual design

elements were liked by some students but marked as confusing or unnecessary by

others. These contradictory findings likely have more to do with personal

design and learning modality preferences than a misreading of the prototypes,

and illustrate that there is no single design approach that will please every

user. Lastly, we found that some of the advanced scribbling data on navigation

is misleading since qualitative feedback illustrates that the problem is the

navigation labels not the menu design. This may be an inherent limitation of

the advanced scribbling protocol that researchers can mitigate by encouraging

marginal annotation in addition to color-coding, and by combining this protocol

with semi-structured interviews.

Areas for

Future Research

This

mixed methods user study raised some questions and illuminated several areas

that require additional research. The authors would like to further explore

relationships between user research experience, learning modality preferences,

and design, perhaps by diversifying the study sample to include more advanced

level researchers and different kinds of learners. While beyond the scope of

this study, the authors acknowledge that different use contexts such as use by

librarians in instruction sessions versus independent use by student

researchers for subject specific LibGuides may impact user design preferences

and influence what features they deem important. The authors question whether

guides should place emphasis on discovery, information literacy, or resource

curation, and how these decisions relate to theoretical and political

conversations about the purpose of online instructional tools. Are the guides

intended to be used by students working independently on research assignments,

as a supplement or replacement for face-to-face instruction? Is the intended

audience for research guides students, classroom faculty, or librarians? Can a

LibGuide serve all of these various purposes and audiences at the same time?

How do these shifting contexts resolve themselves in design? Do LibGuides and

other digital instructional objects have a measurable effect on student

research outcomes and achievement, and could they have more of an impact if

they were deployed or designed differently?

The

authors also hope to conduct more usability testing once the new LibGuides

template is live since computer-based task analysis might present a clearer

picture of how users interact with the LibGuides interface. Alternative

protocols, such as mobile and remote usability testing, should also be deployed

after template implementation to assess whether students have issues with

access or navigation on different devices. Additionally, CUNY is in the process

of acquiring a consortial license for the LibGuides CMS package, which includes

an analytics package. Implementation of the CMS package will introduce more

options for quantitative analysis of usage. Although LibGuides analytics cannot

capture the kind of granular data a usability study can, analytical data can

provide insight into what areas of a guide are used frequently.

Conclusion

This

mixed methods user study yielded important insights into student design and

modality preferences at City Tech. While there is no single design approach

that can satisfy all users’ preferences, there was consensus surrounding

several concrete design features that can be hard-coded into a LibGuides

template. The authors believe that the implementation of a new template and the

creation of custom multimedia assets will make LibGuides more intuitive and

accessible. Additionally, librarian training sessions and institutional efforts

to align research guides with library instruction and reference services may

ultimately enhance pedagogical outcomes and start an important dialogue about

instructional design. While the concrete design outcomes generated from this

study may not be translatable to other institutional contexts, academic

librarians can adopt the methodology articulated here to create effective

LibGuides templates at their own institutions. Additionally, the correlation

between learner preferences and design principles identified here is applicable

to other institutional and platform contexts, and should be studied further.

Ultimately, the authors hope this study will encourage other libraries to focus

on user-centric design and spark a larger discussion about relationships

between instructional design, learning modalities, and research guide use

contexts.

References

Bowen, A.

(2014). LibGuides and web-based library guides in comparison: Is there a

pedagogical advantage? Journal of Web Librarianship,

8(2), 147-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2014.903709

Brumfield, E.

J. (2010). Applying the critical theory of library technology to distance

library services. Journal of Library

& Information Services in Distance Learning, 4(1-2), 63-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332901003765795

City

University of New York. (2017). Online

instruction at CUNY. Retrieved from http://www2.CUNY.edu/academics/current-initiatives/academic-technology/online-instruction/

DeSimio, T.,

& Chrisagis, X. (2014). Rethinking

our LibGuides to engage our students: Easy DIY LibGuides usability testing and

redesign that works [PDF document]. Retrieved from http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ul_pub/168

Dumuhosky, L.,

Rath, L. T., & Wierzbowski, K. R. (2015). LibGuides guided: How research and collaboration leads to success

[PDF document]. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/lib_presentations/2

Duncan, V.,

Lucky, S., & McLean, J. (2015). Implementing LibGuides 2: An academic case

study. Journal of Electronic Resources

Librarianship, 27(4), 248-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2015.1092351

Gimenez, P., Grimm, S., & Parker, K. (2015). Testing and templates: Building effective research

guides [PDF

document]. Paper presented at the Georgia International Conference on

Information Literacy. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/gaintlit/2015/2015/37

Held, T.,

& Gil-Trejo, L. (2016). Students weigh in: Usability test of online library

tutorials. Internet Reference Services

Quarterly, 21(1-2), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2016.1164786

Hertzum, M.,

Borlund, P., & Kristoffersen, K. B. (2015). What do thinking-aloud

participants say? A comparison of moderated and unmoderated usability sessions.

International Journal of Human-Computer

Interaction, 31(9), 557-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1065691

Hicks, A. (2015).

Libguides: Pedagogy to oppress Hybrid

Pedagogy. Retrieved from http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/libguides-pedagogy-to-oppress/

Linek, S. B., & Tochtermann, K. (2015). Paper prototyping: The surplus

merit of a multi-method approach. Forum:

Qualitative Social Research, 16(3). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2236/3836

Martin, B.,

& Hanington, B. M. (2012). A/B Testing. In Universal methods of design: 100 ways to research complex problems,

develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. (pp. 8-9).

Beverly, MA: Rockport. Nielsen, J. (2005). Putting A/B testing in its place. In

Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/putting-ab-testing-in-its-place/

Nielsen, J.

(2012). How many test users in a usability study? In Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users/

Sefelin, R., Tscheligi, M., & Giller, V. (2003, April). Paper

prototyping - What is it good for? A comparison of paper-and computer-based

low-fidelity prototyping. In CHI '03

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (pp. 778-779).

ACM. Retrieved from http://mcom.cit.ie/staff/Computing/prothwell/hci/papers/prototyping-sefelin.pdf

Snyder, C.

(2003). Paper prototyping: The fast and

easy way to design and refine user interfaces. San Francisco: Morgan

Kaufmann.

Sonsteby, A.,

& DeJonghe, J. (2013). Usability testing, user-centered design, and

LibGuides subject guides: A case study. Journal

of Web Librarianship, 7(1), 83-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2013.747366

Spingshare.

(2017). LibGuides. Retrieved from https://www.springshare.com/libguides/

Thorngate, S.,

& Hoden, A. (2017). Exploratory usability testing of user interface options

in LibGuides 2. College & Research

Libraries. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16739

Tohidi, M., Buxton, W., Baecker, R., & Sellen, A. (2006). Getting the

right design and the design right: Testing many is better than one. In CH 2006 Proceedings, April 22-27, 2006,

Montreal, Quebec, Canada. (pp.1243-1252). Retrieved from https://www.billbuxton.com/rightDesign.pdf

U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Higher

Education General Information Survey (HEGIS) (2014). Total undergraduate fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary

institutions, by attendance status, sex of student, and control and level of

institution: Selected years, 1970 through 2023 [Data File]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_303.70.asp

Yoon, K.,

Dols, R., Hulscher, L., & Newberry, T. (2016). An exploratory study of

library website accessibility for visually impaired users. Library & Information Science Research, 38(3), 250-258.

Young, S. W.

H. (2014). Improving library user experience with A/B testing: Principles and

process. Weave: Journal of Library User

Experience, 1(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.101

Appendix A

Interview Questions

1.

Which

research guide do you prefer?

2.

What

don’t you like about the guide you didn’t select?

3.

Which

features of the research guide made you select this guide?

4.

How

much content do you think should be included on a research guide?

5.

What

labels or features did you find confusing?

6.

Do

the menu labels on this guide make sense to you?

Appendix B

Prototype A

⇦

Appendix C

Prototype B

![]() Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice

Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice![]()

![]()

![]() 2017 Almeida and Tidal. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Almeida and Tidal. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.