Introduction

Seneca

Libraries has been an innovator in creating learning objects (LOs) to teach

students information literacy (IL) skills. We realized early the need to

integrate online learning into our instruction strategy. The Seneca Libraries

IL team collects statistics and analyzes data to inform strategic planning and

assure quality and continuous improvement. We analyzed two sets of statistics

in Fall 2010 and Winter 2011. The first set of

statistics considered the total number of one-shot IL classes in foundational

English composition courses. One in five, or approximately 20%, of all IL

classes taught by the library were for foundational English composition

courses, either English & Communication EAC149 (non-credit

developmental course in reading, writing, and oral expression that prepares

students for EAC150), or College English EAC150 (compulsory,

introductory college writing and reading course fundamental to successful

college studies). This represented a significant amount of staff time spent on

instruction.

Approximately

80% of other IL classes were taught in the program disciplines within which

students major. There is currently an initiative to embed and integrate IL

within the program-specific curriculum. Allocating staff to increase the number

of classes taught for English composition would come at the expense of work

already underway embedding IL skills directly into the program specific

courses. Even if more staff could be allocated to English composition, there

would still be scheduling challenges making it nearly impossible for staff to

reach every section face-to-face.

The

second set of statistics looked at the number of EAC149 and EAC150 sections

taught over these two semesters, as a percentage of the total number of

sections (Table 1). We discovered that library instructional staff taught

approximately 24-27% of all sections of EAC150, and approximately 13-17% of all

sections of EAC149. This indicated that the majority of sections for both

courses received no form of IL instruction.

In addition to

these statistics, we also had to take into consideration that while EAC150 is compulsory, students are not obligated to take it

in their first semester. Therefore, it could not be certain that every first

year student was receiving IL instruction. If a student took the course in

their last semester before graduating, they would not have had the opportunity

to practice these skills in other courses, or benefit from the library’s

strategic scaffolding of IL skills throughout their programs.

Table

1

Information

Literacy Classes Taught for Seneca College English Composition Courses

|

Semester

|

Total

number of EAC150 sections

|

Total

number of EAC150 sections taught by library

|

Percentage

(%) of EAC150 IL sections taught by library

|

Total

number of EAC149 sections

|

Total

number of EAC149 sections taught by library

|

Percentage

(%) of EAC149 IL classes taught by library

|

|

Fall 2010

|

132

|

36

|

27

|

105

|

18

|

17

|

|

Winter 2011

|

111

|

27

|

24

|

67

|

9

|

13

|

In the late 1990s,

Seneca Libraries, in collaboration with professors, developed an online

tutorial, Library Research Success, for the Business Management program

at Seneca College. This tutorial

addressed basic business information literacy skills for first year students

deemed foundational. Students would work through the tutorial either in class

or on their own time allowing flexibility in terms of when and where they

learned. Students were also required to complete a low-weighted, graded

research assignment. As reviewing the IL LO was a requirement of the course, we

reached every student. When delivering face-to-face this is not always the

case, given the staffing limitations and scheduling conflicts in the

high-enrollment program. Donaldson (2000), a Seneca librarian and co-creator of

the tutorial, published a qualitative, anecdotal techniques study that

collected data in the form of reviewing completed student assignments for the

tutorial and comments (which were optional) that revealed students’

perceptions. Business professors were also asked to provide informal

feedback through personal interviews. Overall, students performed well on

the assignments, and feedback from students and faculty was positive. The

adoption and success of this tutorial allowed for adaption and customization in

other programs, primarily for use by first year students. However, as over a

decade had passed since this tutorial was created, new technologies and

software had rendered the tutorial outdated.

There were several

issues to be taken into consideration about the English Composition course at

Seneca College. Limited staffing and increasing enrollment meant an inability

to reach every course section. Librarians also wanted to make sure students

received IL instruction early in their studies. Finally, the outdated tutorial

needed a significant upgrade. How could these problems be solved? The answer

was a strategic approach to the development of online learning objects.

In a survey of

best practices in developing online IL tutorials, Holland et al. (2013) found

that nearly all librarians felt it was important for the library to create its

own tutorials in order to showcase their institution and its materials.

Seneca Libraries

recognized that the development of online IL LOs as a strategic initiative

should be aligned with the institution’s goals, whereby “every Seneca graduate

will demonstrate competency in the Seneca Core Literacies” (Seneca College,

2012, p. 10), of which IL is identified as one of the core literacies, and

“faculty will model digital literacy through use of a variety of media and/or

mobile technologies to engage students as partners in learning” (Seneca

College, 2012, p. 13).

The IL team

adopted the following process in order to reach Seneca Libraries’ strategic

goal in developing online IL learning objects:

1. Needs analysis. Surveys were sent to library teaching staff and

English faculty to determine which IL topics were most commonly taught in

class, and which were perceived to be the most challenging or difficult for

students. These results helped identify and prioritize the IL topics to be

developed into LOs. The following were identified as priority, in order of

preference: database searching, academic honesty, evaluating information,

analysis and application, library website, and library catalogue searching.

2. Analysis of current best practices in the

field. National and international electronic mail lists were

queried and responses were taken into consideration. Seneca librarians’

lesson plans and teaching materials were also reviewed. These internal

documents included learning outcomes based on the ACRL’s Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education

(ACRL, 2000). A literature search on the development of IL learning

objects was conducted. From these sources, the most common IL topics developed

into online learning objects were:

·

using online library tools (book catalogue, databases, LibGuides, etc.);

·

evaluating

material and selecting resources;

·

defining a

research topic;

·

searching skills

for the Internet (including Google Scholar);

·

documenting your

research;

·

locating a known journal article.

Instructional

design and development best practices were incorporated into creating our own

set of design principles to optimize student engagement and learning.

3. Inventory of LOs already developed by Seneca

Libraries. Comparing the

list of recommended topics to be developed to the list of existing LOs,

identifying gaps, and prioritizing objects for development.

4. Development of LOs. Allocation of library resources (e.g.,

staffing, software), collaborating with English faculty to design objects,

building prototypes, testing prototypes with small user groups, modifying and

reviewing prototypes and launching beta objects.

An LO is “a

reusable instructional resource, usually digital and web-based, that is

developed to support learning” (Mestre, 2012b, p.

261). Examples of learning objects can

include tutorials, videos, games, and quizzes. A series of IL LOs were

developed over the 2012 spring and summer semesters, and were released in

September 2012 for the start of the fall semester. A Learning Objects

Committee, under the Seneca Library’s Information Literacy (SLIL) Team, was

tasked with this project. The committee was made up of several librarians and

library technicians. The committee chair, the library’s eLearning Technologies

Librarian, was both project manager and technical support. Once the initial

process was completed (needs analysis, best practices, and inventory), the

committee broke into smaller groups responsible for developing individual LOs

by topic. These groups consisted of one to two librarians delegated as content

leads whose main responsibilities were scripting, storyboarding, and quiz

creation. They were partnered with at least one library technician who provided

support for filming, animations, and editing. Each group was further supported

by the committee lead and a library media technician, both of whom helped with

filming, animation, screen casting, audio capture, and software support. Each group

was given permission to proceed with filming and production only after their

scripts were reviewed and approved by the entire committee.

The IL LOs consist

of short, one to three minute videos that include live action recordings,

screen casting, and animations. The main software used was Camtasia. The videos

are all closed-captioned and include a text-based transcript. For introductory

IL videos there is a PDF summary, and for demonstration videos there are PDF

step-by-step instructions with screenshots. By offering the lessons in both

video and text-based formats we hope to offer flexible options for learning.

All LOs have learning outcomes tied to assessments, typically multiple-choice

questions. LOs, accompanying assessments, and documentation are also bundled

into library cartridges, which are zip files that can be imported as one

unit into Blackboard, the institution’s course management system. For

consistency, IL LOs will be herein referred to as videos.

While usability

and design were tested throughout the development process, what remained to be

assessed was the impact the newly created videos had on student IL competency.

Considering the time and effort invested and the goal to teach more students

online, it was vital that these videos contributed positively to student

learning. We determined that the videos needed to be assessed for their

effectiveness in terms of student IL skill acquisition. In early 2013, we were

granted ethics approval from our institution to conduct a research study to investigate

this issue.

Literature Review

Evaluation and Assessment of Online Learning Objects

It was clear we

needed to update Seneca’s first generation of tutorials, and developing a

strategy to evaluate and assess them was paramount. The abundant amount of

literature on learning object development and creation indicates interest and

activity in this area, especially studies which review and survey best

practices (Blummer & Kritskaya,

2009; Mestre, 2012a; Somoza-Fernández

& Abadal, 2009; Su & Kuo,

2010; Yang, 2009; Zhang, 2006). These studies also identified the importance of

building in evaluation and assessment as part of the development process in

order to measure success and effectiveness.

Mestre (2012a) noted the

importance of assessment as a way of measuring success. Mestre (2012a) also stated that assessment should focus on

students’ learning, as well as outcomes and opinions and lists various ways to

document evidence as to whether the goals of the learning object were

accomplished: checkpoints, statistical tracking, log file analysis, Web page

analytics, tracking new accounts, evaluation of student work pre- and

post-tests, student debriefing, and surveys.

Measuring Success: Usability, Student Learning,

Student Perceptions or All of the Above?

The issue on what

aspect to evaluate or assess was evident in several studies. Lindsay,

Cummings, Johnson, and Scales (2006) grappled with this dilemma when they asked

“is it more important to measure student learning or to study how well the tool

can be navigated and utilized?” (p. 431). They settled on capturing both

areas, but without one-on-one usability testing, instead designing “the

assessment modules to gather data from the students about their use of

resources, attitudes towards the libraries, and perceptions of the utility of

the online tutorials” (Lindsay et al., 2006, p. 432). Befus

and Byrne (2011, as cited in Thornes, 2012), found that the success of a

tutorial can be difficult to quantify. They found that despite students

obtaining lower than anticipated scores in the associated test, the tutorial

was still successful because it reached more students with greater flexibility.

Comparisons in

Library Instructional Delivery Methods

Other studies

investigated whether online learning modules were as effective as more

traditional modes of instruction, such as librarian-led, face-to-face classroom

sessions, and most found that the modules were equally effective. Bracke and Dickenson (2002) found that “using an

assignment-specific Web tutorial in conjunction with an instructor-led,

in-class preparatory exercise is an effective method of delivering library

instruction to large classes” (p. 335). Silver and Nickel (2005) developed and

embedded a multiple module tutorial for a psychology course, which was animated

and interactive. Post-tests on material covered, including questions on

confidence level and preferred mode of instruction, showed that there was no

difference between the tutorial and classroom instruction in terms of quiz

results (Silver & Nickel, 2005).

Koufogiannakis and Wiebe’s (2006) systematic review of 122 unique

studies found that instruction provided electronically was just as effective as

more traditional instruction. Specifically, “fourteen studies compared

[Computer Assisted Instruction] CAI with traditional instruction (TI), and 9 of

these showed a neutral result. Meta‐analysis of 8 of these studies agreed with

this neutral result” (Koufogiannakis & Wiebe, 2006, p. 4). Kraemer et al.

(2007) compared three instructional methods: online instruction only, live

instruction, and a hybrid combination in a first-year writing course. They

concluded with a “high degree of confidence that significant improvement in

test performance occurred for all subjects following library instruction, regardless

of the format of that instruction” (Kraemer et. al., 2007, p.

336). Similarly, as part of the curriculum for a general education course,

Anderson and May (2010) tested the following IL topics across three conditions:

library catalog, academic databases, Boolean searching, and evaluation of

sources materials. Their results indicated that the way in which

instruction is delivered does not affect the students’ ability to retain the

information taught (Anderson & May, 2010). Sachs et al. (2013) also found

that Millennial students learned equally well from

both HTML-based tutorials and dynamic, interactive audio/video

tutorials. However, they also found that “students expressed a much higher

level of satisfaction from the tutorial designed to be ‘Millennial friendly’”

(Sachs et. al., 2013, p. 1).

Instructional Effectiveness of Online Learning Objects

While previous

studies point out that online tutorials can be just as effective as

face-to-face classroom instruction and in effect, compare modes of delivery,

another branch of literature compares different types of online tutorials for

their instructional effectiveness. Mestre (2012b)

found “that a screencast tutorial with images can be more effective than a

screencast video tutorial” (p. 273) for 16 out of 21 students tested. In

contrast, Mery et al. (2014) found that there was no

impact on student performance between two types of instruction, one form of

receiving information from passively watching a screencast, and the other form

rooted in active learning, the Guide on

the Side. Despite limitations to the study, Mery

et al. (2014) still asserted that “database instruction can successfully be

taught online in a number of ways from static tutorials to highly interactive

ones” (p. 78).

Mixed Methodology Studies

As mentioned

earlier, most studies invariably have some form of usability testing, along

with some measure on student learning through testing content, pedagogical

approaches, or student learning styles or preferences. Johnston (2010)

investigated first year social work students’ opinions on IL, while also

gathering feedback on the tutorial, and assessing students’ skills. They

employed a mixed methods approach with quantitative and qualitative research

methods that included a survey, focus groups, empirical data from task results,

and observations (Johnston, 2010, p. 211). The majority of students were given

tasks to complete and researchers evaluated if those tasks were completed

efficiently; however, an exact measurement was not specified or elaborated on.

Findings indicate that students efficiently completed their tasks involving

evaluating websites and finding cited and relevant information using Google,

while they struggled with tasks involving databases, including search

techniques, and differentiating between databases and other sources of

information (Johnston, 2010). An observational study by Bowles-Terry et

al. (2010) “examined the usability of brief instructional videos but also

investigated whether watching a video tutorial enabled a student to complete

the task described in the tutorial” (p. 21). Their findings informed best

practices in the following categories: pace, length, content, look and feel,

video vs. text, findability, and interest in using video tutorials (Bowles-Terry

et al., 2010). They also pointed out that future research is needed,

particularly performance-based assessments as they “would give great insight

into how well videos can be used to teach and whether their effectiveness is

restricted to students with particular learning styles and/or specific content,

for example, procedural, rather than conceptual” (Bowles-Terry et al., 2010, p.

27). Adapting these models of evaluation or assessment with a focus on

measuring student learning, particularly through quantitative methods, seemed

to make the most sense for our learning objects. Taking into consideration that

usability studies have been done throughout the development and prototype cycle

of our project, measuring how our learning objects impact student learning seemed

to be the most pressing issue to investigate.

Aims

The aim of this

preliminary quantitative study is to ascertain whether library-developed IL LOs

impact student IL competency in comparison to traditional face-to-face

instruction in a first year English composition foundation course. If the

LOs impact student IL competency in the same way, or to a greater degree as

face-to-face instruction, then this evidence can be used to inform the use,

development, and assessment of IL LOs in the library’s IL program. No previous

research of this kind has been carried out by Seneca Libraries. The

secondary aim was to measure, through pre- and post-testing, if there is a

statistically significant difference in student performance for any one of the

three pre-selected IL topics as a success indicator for one method of instruction,

e.g. online or traditional face-to-face. Results of this study can help inform

the LO development process, in addition to future assessment studies of IL LOs.

It can also be used to add to the wider discussion of the use and development

of IL LOs in secondary education.

Methods

Type of Assessment

The literature

distinguishes between two different types of evaluation and assessment: 1.

Measurement throughout the development and prototype cycle in order to inform

design or structural changes in the form of usability testing, and; 2.

Measurement of student learning by testing different pedagogical approaches and

student learning behaviour. Most studies invariably

have some form of usability testing, along with some type of measurement on

student learning.

In our case,

adoption of best practices meant that informal usability testing occurred

throughout the development and prototype cycle for learning object development,

albeit informally and therefore inconsistently. In specific, two methods of

assessment, as identified by Mestre (2012a) were

used, and would fall under the first type of assessment mentioned above:

- Pilot (beta) testing. During script and

storyboard development, student library workers, individually or in small

groups of two or three, were sporadically recruited and asked for input.

- Student feedback. Informal feedback was obtained

either individually during reference interviews, or as small groups,

during in-class IL sessions. General, open-ended questions were asked and

responses recorded by a library technician or librarian. Questions were

not standardized.

In this way,

design could be continually improved to meet the needs of the users. With

a reasonable amount of confidence, we felt that the second generation of

modules we were building had solid design principles based on the best

practices and experiences set by other academic libraries. The main variation

with our modules was the customization to the local context so that Seneca

Libraries’ resources, students, and course-specific research challenges were

represented. Recommendations from usability studies helped guide our learning

object development (Bury & Oud, 2005; Lund & Pors,

2012; Mestre, 2012b).

This preliminary

study focused instead on the second type of assessment, measuring student

learning. While building on earlier similar studies (Anderson & May, 2010;

Gunn & Miree, 2012; Johnston, 2010; Kraemer et.

al., 2007; Mery et al., 2014; Zhang, Goodman, & Xie, 2015), the departure lies mainly with a focused or

narrow method by testing only student performance. Quantitative student test

results were analyzed through determining statistical significance for each of

three information literacy topics.

Data Collection

To

measure the effectiveness of the videos in terms of students’ skill

acquisition, a preliminary quantitative study was initiated. Ethics approval

was obtained from the institution and all students consented to take part in

the study. Participation was

optional and students could choose to exit the study at any time. Results

were anonymous and did not impact student grades.

We

decided to conduct our study in the foundational English composition course, College English EAC150. This

is a compulsory course for students and so an ideal student population to test

for basic IL skills. More importantly, librarians had been partnering with

English faculty for several years, delivering face-to-face one-shot

instructional sessions tailored to the learning outcome in the course

syllabus. Students were required to produce effective research writing

through the completion of a research project. Students had incentive to

participate as the information learned through the study would help them

complete the research project in the course.

The

study was carried out over two semesters; 75 students participated in the Winter (January to April) 2013 semester (herein referred to

as Group 1), and 35 students participated in the Fall (September to December)

2013 semester (herein referred to as Group 2). A librarian and a library technician led each group. In each, the students were first assessed for their

IL skills competency through completing an online pre-test of multiple-choice

questions. The students were then exposed to one of two interventions:

online videos or face-to-face, librarian-led instruction. After the

intervention, the students were given the same test again. For the videos

intervention, these consisted of three newly created online videos that were

produced in house: Finding

Articles, Finding Articles on Current Issues, and Popular and Scholarly Sources.

The learning

outcomes were standardized across the two interventions so that the

face-to-face classes taught to the same learning outcomes as the videos. The learning

outcomes for Finding Articles were

(The learner will be able to…): 1. Select appropriate database(s) by subject or

discipline as related to their research topic; 2. Perform a basic search in a

database; and 3. Understand various mechanisms for retrieving articles

(printing, emailing, saving). The learning outcomes match the lower-order

skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy which fall under knowledge or remembering (Krathwohl, 2002). The learning outcomes for Finding Articles on Current Issues were

(The learner will be able to…): 1. Select

social sciences, news and current events databases; 2. Perform searches based

on research topic; and 3. Evaluate results for relevancy. The learning outcomes

for Popular and Scholarly Sources were (The learner will be able

to…): 1. Differentiate between popular and scholarly literature; 2. Identify

characteristics of a scholarly article; and 3. Select the appropriate type of

article for their research needs. The learning outcomes for these last two

videos match higher-order skills under analysis according to Bloom’s Taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002).

For the video

intervention, students were asked to view the videos independently using their

own headphones, or headphones were made available and distributed. Students

then completed the online test and results were gathered through the online

tool, SurveyMonkey. All questions were multiple

choice and were based on the content in the videos. The questions were written

by librarians who developed the videos and were the main assessment tools used

to test student understanding of the content found in each video. The questions

were independently reviewed by a library technician who matched each question

against the script (content) in the video as a measure for quality control. For

the face-to-face, librarian-led instruction

intervention, students were presented with the same content (and learning

outcomes) as the three videos. The same library staff moderated both

interventions, for the same campus location, to ensure consistency in pacing

and content. If students had technical issues with the online test,

library staff provided support. If students had any additional questions in

regards to the content, e.g. seeking help with question clarification, library

staff would provide guidance but were mindful of not providing overt clues that

could inadvertently point to the correct answers.

In Group 1, 40

students were exposed to the online videos intervention, and 35 were exposed to

the face-to-face, librarian-led instruction. The online test consisted of

fifteen multiple-choice questions (Appendix A), in which there were five

questions for each of the three videos.

In Group 2, 18

students were exposed to the online videos intervention, and 17 were exposed to

the face-to-face, librarian-led instruction. The online test consisted of 14

multiple-choice questions, in which there were 5 questions for 2 videos, and 4

questions were given for the video Finding

Articles on Current Issues (Appendix A). Unfortunately,

one question had to be withdrawn from the test because it no longer made sense

in light of a significant structural change to the homepage of the library’s

website. We decided to delete the question, rather than replace it, since the

answers were not likely to be comparable when analyzing results.

The

main research question was: What is the

effectiveness of videos, in comparison to face-to-face instruction, in terms of

students’ skill acquisition?

Statistical Analysis

General

descriptive statistics were run for the individual pre and post-tests for each

of the groups. Considering that the current research project was preliminary in

nature, comparisons were only made between the pre-tests of the videos and

face-to-face groups for each of the topics as well as the post-tests of the

videos and face-to-face groups for each of the topics through independent

samples t-tests. Unfortunately, repeated measures could not be used to compare

pre-tests and post-tests for each topic due to the fact that the tests were

anonymous and it was not possible to match the pre-test and post-test for each

participant.

Results

Pre-test

measurement of students, in each of the three topic areas, was done to

determine pre-existing skill level. We anticipated that the post-test

measurement would be affected after applying an intervention, either exposure

to an online module or a face-to-face class. In either case, we hoped that an

increase in test scores would indicate learning.

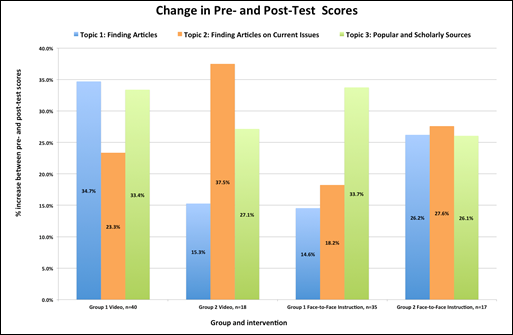

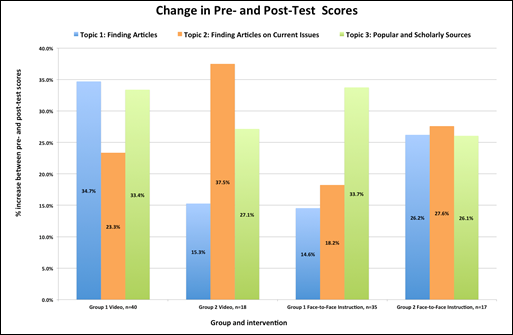

Findings

showed that test scores improved regardless of intervention. The lowest test

score increase, averaged across a group of 35 students, was 14.6% for

face-to-face (Figure 1). The highest test score increase, averaged across a

group of 18 students, was 37.5% for videos (Figure 1).

When

pooling results for both groups, and running a t-test between the video group pre-test and face-to-face group pre-test for each of

the topics, results indicated that both groups were not significantly different

in their knowledge of the three topics.

Similarly,

a t-test was used in comparing post-tests results for video to the face-to-face

across both groups for each of the topics. Independent samples test results

revealed a statistically significant difference with the first topic, Finding Articles, t(110)

= 2.25 and p = 0.026. The videos group outperformed the face-to-face

group by at least 10%. No significance, in terms of performance from pre-

and post-test scores, was found for the other two topics: Finding

Articles on Current Events, t(110) = -1.11 and p = 0.2688,

and Popular & Scholarly t(110)

= -0.009 and p = 0.993.

Figure

1

Change

in pre- and post-test scores amongst Group 1 and Group 2 for both

interventions, online videos and face-to-face instruction.

For

the first topic, Finding Articles, scores

for both Groups 1 and 2 increased on average 34.7% and 15.3% respectively for

the video group (Figure 1). In comparison, scores increased on average 14.6%

and 26.2% respectively for the face-to-face group. The highest average

post-test scores were found for the video group (Figure 1). On average, the

mean test scores were higher in the post-test for both groups (Figure 2).

For

the second topic, Finding Articles on

Current Issues, scores for both Groups 1 and 2 increased on average

23.3% and 37.5% respectively for the video group (Figure 1). In comparison,

scores increased on average 18.2% and 27.6% respectively for the face-to-face

group. In this case, pre- and post-test scores were consistently the lowest

(Figure 2).

For

the third topic, Scholarly &

Popular Sources, scores for both Groups 1 and 2 increased on average

33.4% and 27.1% respectively for the video group (Figure 1). In comparison,

scores increased on average 33.7% and 26.1% respectively for the face-to-face

group. Similar to the first topic, this topic also had the highest post-test

scores in the video group (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mean Test Scores:

Groups 1 and 2 combined. *Please note that for Topic 2, data set for Group 2 normalized to 5 from 4.

Discussion

Similar to

previous studies (Anderson & May, 2010;

Kraemer et. al., 2007; Koufogiannakis & Wiebe, 2006; Silver & Nickel, 2005) this preliminary

study reaffirmed that exposure to IL instruction, regardless of method of

delivery—either through online modules or face-to-face librarian

instruction—increases IL skills of students. Overall, for both groups there was

an increase in test scores after online and face-to-face instruction. On average,

test scores increased between 14 to 37% where the

lowest test score increase, averaged across a group of 35 students, was 14.6%

for face-to-face and the highest test score increase, averaged across a group

of 18 students, was 37.5% for videos. However, as this analysis was

descriptive in nature, we also sought to determine if there was real

statistical significance to these increases.

When comparing

online modules to face-to-face instruction, we found one instance in which

online modules outperformed face-to-face library instruction. For both groups,

the difference in post-test scores for students exposed to online videos

compared to those exposed to face-to-face instruction, was statistically

significant only for one topic, Finding

Articles. In this instance, we can say with a reasonable amount of

confidence, that the video outperformed face-to-face instruction. For this

topic, students exposed to the videos outperformed those students exposed to

face-to-face instruction by at least 10%. Perhaps this topic was better

suited for online learning because the learning outcomes for this particular LO

were task-based, and required lower-order thinking. Perhaps these simple

step-by-step tasks and instructions were better demonstrated through an online,

video-based environment. Further observation would be needed to understand why

this may be the case.

There was no

statistical significance in results for the other two topics, Finding Articles on Current Issues,

and Popular and Scholarly

Sources. For these two topics,

whether instruction is delivered online or face-to-face had no impact on

student performance, unlike the Finding Articles topic. One reason for this may

be that the learning outcomes for these topics required higher-order thinking,

thus making it more difficult to learn, regardless of whether it was taught

online or face-to-face.

We can therefore

conclude that a video, built following best practices and customized to a

program’s curriculum and student body, can have the same, if not better, impact

on students’ uptake of IL skills in comparison to live, face-to-face

librarian-led led classes. In addition, because our findings showed statistical

significance with one topic (Finding Articles), it indicates particular IL

topics are better suited for delivery in an online environment. This area of

study, applying statistical significance through t-tests as it relates to

specific IL topics, is less represented in the literature than the overall

usability and effectiveness of IL tutorials or modules.

Another point of discussion is whether or not the

text-based transcripts of each video had an impact on student learning. This

was not studied separately, but could be considered another method of

instruction in addition to online video and face-to-face instruction that would

need further investigation. The proven efficacy of the IL LOs have encouraged

further usage of the text-based transcripts and summaries in subsequent LOs.

This preliminary

study had limitations. Firstly, while we did perform an independent t-test to

show differences in group averages, we could not perform a paired, or

dependent, t-test which would have been possible had we tracked the identity of

each individual participant. A paired, or dependent, t-test analysis would have

looked at the sampling distribution of the differences between scores, not the

scores themselves. Thus, we would have been able to track differences in test

scores, for each individual student, rather than looking at pooled averages.

Secondly, a mixed

methodology approach would have been useful. More data would be captured for

interpretation through combining quantitative and qualitative methods. Measuring

the differences in student performance for teaching method (online vs.

face-to-face) and IL topic (three different topics) was the quantitative

measurements. We combined this with the measurements of collecting demographic

data on students, focus groups, and observational user testing. We would not

only have the ability to analyze test scores, but would also have the ability

to see correlations.

Thirdly, while the

sample size was reasonable, at 110 participant students we did not obtain the

total number of students enrolled in all sections of College English, EAC150

for those two semesters. We cannot assume that our sample size accurately

represents the average or normal behaviour

of all students enrolled in this course. We would need to obtain this figure,

and compare our smaller sample size as a percentage.

Conclusions

This preliminary

quantitative study gathered evidence in helping to determine whether library

developed IL LOs impact student IL competency in comparison to traditional

face-to-face instruction in a first year foundational English composition

course. This study found that both IL LOs (videos) and face-to-face

instruction have a positive impact by increasing students’ IL test scores. Only

one video on the topic Finding

Articles outperformed face-to-face instruction. Further work, in the

form of a mixed methodology study, would be beneficial in identifying how

specific characteristics, for both online modules and face-to-face instruction,

impact student acquisition of IL skills.

References

Anderson, K., & May,

F. A. (2010). Does the method of instruction matter? An experimental

examination of information literacy instruction in the online, blended, and

face-to-face classrooms. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(6),

495–500. http://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2010.08.005

Association of College

& Research Libraries. (2000). Information Literacy Competency Standards

for Higher Education [Guidelines, Standards, and Frameworks]. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.

Befus, R., & Byrne, K. (2011).

Redesigned with them in mind: Evaluating an online library information literacy

tutorial. Urban Library Journal, 17(1) Retrieved from http://ojs.gc.cuny.edu/index.php/urbanlibrary/index

Blummer, B. A., & Kritskaya,

O. (2009). Best practices for creating an online tutorial: A literature review.

Journal of Web Librarianship, 3(3), 199-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19322900903050799

Bracke, P. J., & Dickstein,

R. (2002). Web tutorials and scalable instruction: Testing the waters. Reference

Services Review, 40(3), 330–337.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320210451321

Bury, S., & Oud, J.

(2005). Usability testing of an online information literacy tutorial. Reference

Services Review, 33(1), 54–65.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320510581388

Donaldson, K. A. (2000). Library research

success: Designing an online tutorial to teach information literacy skills to first-year

students. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(4), 237-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00025-7

Gunn, M., & Miree, C. E. (2012). Business information literacy teaching

at different academic levels: An exploration of skills and implications for

instructional design. Journal of

Information Literacy, 6(1), 17-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/6.1.1671

Johnston, N. (2010). Is

an online learning module an effective way to develop information literacy

skills? Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 41(3),

207–218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2010.10721464

Koufogiannakis, D., & Wiebe, N. (2006). Effective

methods for teaching information literacy skills to undergraduate students: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 1(3), 3–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8MS3D

Kraemer, E. W., Lombardo,

S. V., & Lepkowski, F. J. (2007). The librarian,

the machine, or a little of both: A comparative study of three information

literacy pedagogies at Oakland University. College & Research Libraries,

68(4), 330–342. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.4.330

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002).

A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Lindsay, E. B., Cummings,

L., Johnson, C. M., & Scales, B. J. (2006). If you build it, will they

learn? Assessing online information literacy tutorials. College &

Research Libraries, 67(5), 429–445. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.67.5.429

Lund, H., & Pors, N. O. (2012). Web-tutorials in context: affordances

and usability perspectives. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 13(3),

197–211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14678041211284731

Mery, Y., DeFrain,

E., Kline, E., & Sult, L. (2014). Evaluating the

effectiveness of tools for online database instruction. Communications in

Information Literacy, 8(1), 70–81.

Retrieved from http://www.comminfolit.org/

Mestre, L. S. (2012a). Designing

effective library tutorials: A guide for accommodating multiple learning

styles. Retrieved from ProQuest Safari Books Online database.

Mestre, L. S. (2012b). Student preference for

tutorial design: A usability study. Reference Services Review, 40(2),

258-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907321211228318

Sachs, D. E., Langana, K. A., Leatherman, C. C., & Walters, J. L.

(2013). Assessing the effectiveness of online information literacy tutorials

for millennial undergraduates. University Libraries Faculty & Staff Publications. Paper 29. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/library_pubs/29

Seneca College. (2012). Academic

Plan 2012 - 2017 [Planning documentation]. Retrieved from http://www.senecacollege.ca/about/reports/academic-plan/index.html

Silver, S. L., &

Nickel, L. T. (2005). Are online tutorials effective? A comparison of online

and classroom library instruction methods. Research Strategies, 20(4),

389–396. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2006.12.012

Somoza-Fernández, M., & Abadal, E.

(2009). Analysis of web-based tutorials created by academic libraries. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(2), 126–131. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2009.01.010

Su, S.-F., & Kuo, J. (2010). Design and development of web-based

information literacy tutorials. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(4),

320–328. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2010.05.006

Thornes, S. L. (2012).

Creating an online tutorial to develop academic and research skills. Journal

of Information Literacy, 6(1), 82–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/6.1.1654

Yang, S. (2009).

Information literacy online tutorials: An introduction to rationale and

technological tools in tutorial creation. The Electronic Library, 27(4),

684–693. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640470910979624

Zhang, L. (2006).

Effectively incorporating instructional media into web-based information

literacy. The Electronic Library, 24(3), 294–306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640470610671169

Zhang, Q., Goodman, M., & Xie, S. (2015). Integrating library instruction into the

course management system for a first-year engineering class: An evidence-based

study measuring the effectiveness of blended learning on students’ information

literacy levels. College & Research

Libraries, 76(7), 934-958. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.934

Appendix A

Pre and Post Test Questions (please note italicized indicates correct answer)

Topic: Finding Articles

1. Where do you go on the

library website to find databases?

a)

Library catalogue

b)

Articles Tab

c)

Repositories

d)

All of the above

2. To find a database

with articles about Canadian politics, you should try:

a) Browsing the alphabetical list of

databases

b) Any database will have the articles

on your topic

c)

Select the subject that best matches

your topic from the drop down list of subjects

d)

All of the above

3. Where in an article

record will you find article information like journal title, date of

publication, and page number?

a)

Abstract

b)

Source

c)

Subject Terms

d)

Author

4. What should you do if

the database you are searching doesn’t have enough articles on your topic?

a)

Try a different database

b)

Go to Google

c)

Use the library Catalogue

d)

Give up

5. What are your options

for saving articles?

a)

Print

b)

Bookmark

c)

Email

d)

All of the above

TOPIC: Finding Articles on Current Issues

1. You are doing a

research assignment and need information on a topic that was recently covered

in the news. Where is the best place to start?

a)

Google

b)

A specific database for current

events

c)

Wikipedia

d)

The library catalogue

2. Which category of

databases is the best to use to find articles on current issues?*

a)

General

b)

Science and Technology

c)

Business

d)

News and Current Events

*[Please note that this

question was withdrawn from the test for Group 2 only as it no longer was

relevant in light of a significant structural change to the homepage of the

library’s website. It was decided it was best to delete the question, rather

than replace it since the answers were not likely to be comparable when

analyzing results.]

3. Of the following list,

which database offers a concise list of current events?

a)

AdForum

b)

Academic OneFile

c)

Opposing Viewpoints

d)

Canadian Newsstand

4. What information can

be found about a current issue in the database Opposing Viewpoints?

a)

Statistics

b)

Journal articles

c)

Viewpoints

d)

All of the above

5. How can you search for

current issues in the database Opposing Viewpoints?

a)

Click Browse Issues or type in an

issue of your own

b)

Click Latest News and

choose from a list

c)

Click Resources and

choose a category

d)

Click Search History to

see what issues other people have searched

Topic: Popular and Scholarly Sources

1. When searching for

information, the best place to start is…

a)

Google

b)

iTunes U

c)

Twitter

d)

Seneca Libraries Website

2. Popular articles can

be…

a)

News stories

b)

Reviews

c)

Topic overviews

d)

All of the above

3. Scholarly articles

usually come from...

a)

Journals

b)

Newspapers

c)

Magazines

d)

Blogs

4. It is sometimes

difficult to determine whether or not an article comes from a journal. Which statement

does NOT apply to scholarly articles?

a)

are usually several pages

long

b)

does not need to contain a list of

references

c)

are divided into sections,

the first section of which is usually an abstract or synopsis.

d)

are written by a scholar

or expert within the subject discipline

5. In order to ensure

quality, journals are often…

a)

Board reviewed

b)

Peer reviewed

c)

Panel reviewed

d)

Technically reviewed

![]() 2016 Bordignon, Otis, Georgievski,

Peters, Strachan, Muller, and Tamin. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2016 Bordignon, Otis, Georgievski,

Peters, Strachan, Muller, and Tamin. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.