Article

Charting Success: Using Practical Measures to Assess

Information Literacy Skills in the First-Year Writing Course

Ann Elizabeth Donahue

Interim Dean

Dimond

Library

University of New Hampshire

Durham, New Hampshire,

United States of America

Email: [email protected]

Received: 21 Feb. 2015 Accepted:

13 May 2015

![]() 2015 Donahue. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Donahue. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

The aim was to measure the impact of a peer-to-peer model on information

literacy skill-building among first-year students at a

small commuter college in the United States. The University of

New Hampshire (UNH) is the state’s flagship public university and UNH

Manchester is one of its seven colleges. This study contributed to a program

evaluation of the Research Mentor Program at UNH Manchester whereby peer

writing tutors are trained in basic library research skills to support

first-year students throughout the research and writing process.

Methods

–

The methodology employed a locally developed pre-test/post-test instrument with

fixed-choice and open-ended questions to measure students’ knowledge of the

library research process. Anonymized data was collected using an online survey

with SurveyMonkey™ software. A rubric was developed to score the responses

to open-ended questions.

Results

–

The study indicated a positive progression toward increased learning for the

three information literacy skills targeted: 1) using library resources

correctly, 2) building effective search strategies, and 3) evaluating sources

appropriately. Students scored higher in the fixed-choice questions than the

open-ended ones, demonstrating their ability to more effectively identify the

applicable information literacy skill than use the language of information

literacy to describe their own research behavior.

Conclusions

–

The assessment methodology used was an assortment of low-key, locally-developed

instruments that provided timely data to measure students understanding of

concepts taught and to apply those concepts correctly. Although the conclusions

are not generalizable to other institutions, the findings were a valuable

component of an ongoing program evaluation.

Further assessment measuring student performance would strengthen the

conclusions attained in this study.

Introduction

Due to limited budgetary and staffing issues, small

academic libraries within the United States face a cornucopia of challenges

when delivering a broad spectrum of services to their constituents. These

challenges often engender innovative and creative solutions that yield

delightful and unexpected outcomes. The Research Mentor Program at the

University of New Hampshire (UNH) Manchester is one of those happy circumstances.

Through this program, research mentors become the conduit whereby the

librarians are able to extend academic support beyond the library walls to

reach first-year students at each stage of the research process – from

brainstorming topics; developing effective search strategies; evaluating sources to preparing outlines;

developing thesis statements; and drafting through the writing/revision cycle.

In the Research Mentor Program, the Library partnered

with the College’s Center for Academic Enrichment (CAE) to improve students’

information literacy skills in all First-Year Writing courses. One critical

component of this collaboration was the incorporation of peer writing tutors

trained in basic library research skills who worked side-by-side with the

instruction librarians in the classroom as research mentors to first-year

students. The UNH Manchester librarians recognize research and writing as an

integrated process and used this approach to provide these students with

essential support throughout the research process. Within the classroom,

research mentors worked with librarians to model effective research strategies.

Outside the classroom, they worked directly with students in individualized

tutorials.

Small class size and teaching excellence are hallmarks

of UNH Manchester. First-Year Writing courses are capped at 15 students and

generally six sections of the course are offered each semester. The Library’s

information literacy instructional plan includes three 90-minute sessions per

section to scaffold learning in manageable units each building upon the

previous unit. This intense delivery model is a deliberate effort to meet

students' developmental readiness levels and to embed information literacy into

the curriculum of the composition program.

The genesis for the Research Mentor Program came from

an idea presented in a poster session at an Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) annual conference. The original design utilized students

trained in basic library research techniques to assist other students with

their research projects at evening and week-end drop-in sessions held in the

residence halls. By modifying the delivery method to accommodate a commuter

campus, capitalizing upon the College's collaborative culture and partnering with

the CAE’s successful peer tutoring enterprise, the UNH Manchester Library was

able to experiment with an innovative, student-centered approach to increasing

information literacy competencies (Fensom, McCarthy, Rundquist, Sherman, & White, 2006; White & Pobywajlo, 2005).

The program has evolved since its inception in 2004.

Although originally focused on serving the students in the First-Year Writing

course, in the Fall semester of 2013 the program reach

was extended to include the use of peer research mentors across the disciplines

and in upper-level courses. Each of the three members of the Library's

instruction team had a significant role in ensuring the success of the program.

The Information Literacy Instruction Coordinator partnered with the Director of

the CAE to design and teach the two to four credit-bearing Tutor Development

course required of each peer writing tutor. The Information Literacy Specialist

developed the course objectives and delivered instruction for all sections,

partnering with the research mentors to include modeling of best practice

techniques through a peer-to-peer lens. The Library Director collaborated with

the instruction team to craft effective assessment instruments, liaised with

the teaching faculty and administration to ensure adherence to research

protocol, and analyzed the data collected.

During the first seven years of the program, anecdotal

evidence suggested the program was a successful one, but a systematic

evaluation that provided clear evidence was long overdue. In the academic year

2011, the library instruction team planned and implemented the first phase of a

program evaluation to gather data to assess the impact of this peer-to-peer

model on student learning. Beginning with a pilot study in the Spring 2011 semester, the study continued through the next

two semesters resulting in data that highlighted strengths and indicated areas

for improvement. This paper discusses selected quantitative and qualitative

findings from this eighteen-month study measuring the effectiveness of

delivering information literacy through a peer-to-peer approach, replacing the

traditional one-shot library instruction methodology with semester-long

engagement in information literacy skill-building.

Literature Review

The professional literature describes a variety of

collaborations that exist between the academic library and the college writing centre. Some examples defined shared-space arrangements

leading to mutually beneficial opportunities that enhanced student services

(Currie & Eodice, 2005; Foutch,

2010; Giglio & Strickland, 2005). Other examples

described joint workshops led by instruction librarians and the professional

writing staff focused on improving student learning outcomes (Artz, 2005; Boff & Toth, 2005; Cooke & Bledsoe, 2008; Leadley

& Rosenberg, 2005). Further examples discussed the use of peer tutors

serving in an assortment of roles from marketing ambassadors to basic research

support assistants (Cannon & Jarson, 2009; Deese-Roberts & Keating, 2000; Furlong & Crawford,

1999; Gruber, Knefel & Waelchli,

2008; Lowe & Lea, 2004; Millet & Chamberlain, 2007).

When library collaborations with writing centres utilized student peer tutors rather than

professional staff a new dimension – peer-to-peer learning – made it possible

to extend the reach of the librarians beyond the instruction class. When these

collaborations involved an aspect of research or instruction assistance,

various levels of training were incorporated to prepare these student peer

tutors to develop the basic skills necessary for engaging with research

strategies and processes. This training provided the peer tutors with critical

foundational skills that enabled them to directly respond to research questions

that arose during writing tutorials.

A classroom clinic, co-led by instruction librarians

and student peer tutors, is described in an article by Gruber et al. (2008).

This collaboration was crafted to respond to assignment-specific objectives

that reflected information literacy standards and effective writing criteria.

The alliance between librarian, faculty, and peer tutor enabled the students in

the course to participate in small group experiences, facilitated by either the

librarian or peer tutor, in order to grapple with identifying the key elements

of scholarly inquiry and evaluating academic journal articles.

At the University of New Mexico, Deese-Roberts

and Keating (2000) discussed the collaboration between the library and the

writing centre whereby peer writing tutors were

trained by librarians in “five key concept areas: (1) library services and

policies; (2) search strategies; (3) Boolean logic, search logic, and limits;

(4) vocabulary (controlled vs. natural); and (5) database structure” (p. 225).

Peer writing tutors then worked with students on research and writing projects.

Assessment of the pilot program indicated positive feedback from all

stakeholders. The assessment focused on user satisfaction and participation.

Student participation in the program “increased 100% from the first to the

second semester” (p. 228) inspiring the authors to declare the pilot program a

success.

Elmborg (2005) suggested that peer tutors work effectively because they

“understand the student perspective . . . they live that perspective” (p. 15).

Nelson (1995) proposed that peer tutors were well situated to assist less

capable students because they empathized and guided comprehension more

effectively since they “speak the language of other undergraduates more

distinctly than graduate students and professors” (p. 45). Lowe and Lea (2004)

defined the peer tutor in an academic setting as “a person who helps you over

bumps and makes you realize that you really can do it – whatever it is – by

yourself” (p. 134).

Several academic libraries have incorporated

undergraduate students in their instruction programs. The role of these

students varied from facilitating small group discussions (Gruber et al., 2008)

to roaming the classroom providing assistance during hands-on activities (Deese-Roberts & Keating, 2000) to teaching mini-seminars

on specific library resources (Holliday & Nordgren,

2005). As the demand for library instruction in lower-division general

education courses grew to unsustainable levels, librarians at California

Polytechnic State University implemented a “student-based solution” (Bodemer, 2013, p. 578). Undergraduate students serving as

reference assistants received additional training in instructional design, were

designated as peer instructors, and worked alongside the librarian in the

classroom. The online evaluations for each session showed that students ranked

these peer instructors higher than the librarians on an affective scale (Bodemer). Based on these evaluations, the student peer

instructors were assigned to lead basic information literacy sessions independently.

At UNH Manchester, the peer tutor program was already

a College Reading and Learning Association certified program that was highly

effective and recognized the benefits of students helping students. By

enhancing the writing tutor’s toolkit with information literacy skills and

integrating them into the instruction sessions to model good research behaviour, these research mentors became better equipped to

guide first-year students through the entire research process.

Aims

The impetus for undertaking a program evaluation study

was the imminent retirement of the Director of the CAE. As the search for a new

director began, it became apparent that there was no measurable evidence

available to support continuation of a program deemed valuable to the

stakeholders. Whenever the program's value was discussed, its success was

attributed to the connections forged through "a network of people

dedicated to helping [students] achieve their academic goals” (White & Pobywajlo, 2005). Yet no data existed to support this claim

as no evidence that students' achieved their goals was ever collected. It was

time to formalize assessment and develop a plan that would measure the impact

of the program. In Fall 2009, the information literacy

instruction team began building an assessment plan to evaluate the program.

Although it was agreed that improving teaching and learning were important

goals for this evaluation, demonstrating the program's effectiveness and value

to ensure the continuation of the program was an essential purpose for this

study.

A review of the program objectives identified by both

the library and the CAE suggested a three-phased approach for the program

evaluation plan: 1) measure change in students' information literacy skills in

First-Year Writing courses and their self-perceptions of confidence with the

research process, 2) examine peer tutor experiences and their perceptions of

self-development as a result of participating in the program, and 3)

investigate faculty perceptions of their students' learning outcomes

attributable to the program's peer-to-peer model.

Both departments shared common objectives for student

success that focused primarily on increasing critical thinking, improving

research and writing skills, and giving students the tools to become

information literate. These objectives became the goals measured during the

initial phase of the program evaluation. The aim of the program evaluation was

to measure the impact of a peer-to-peer model on information literacy

skill-building among first-year students. This paper presents selected results

from the initial phase of the program evaluation which measured the impact on

information literacy skills.

Methodology

The study received Institutional Review Board protocol

approval in January 2011, and a pilot study was implemented that Spring

semester. All students enrolled in a First-Year Writing course were invited to

participate in the study. The size of the college (approximately 900

undergraduates) resulted in a small pool of potential participants. Although

random sampling was a desired method, the capped enrolments in these courses

made convenience sampling the most logical approach to obtain a

reasonably-sized data pool. Participation was voluntary, and students could opt

to leave the study at any time during the semester.

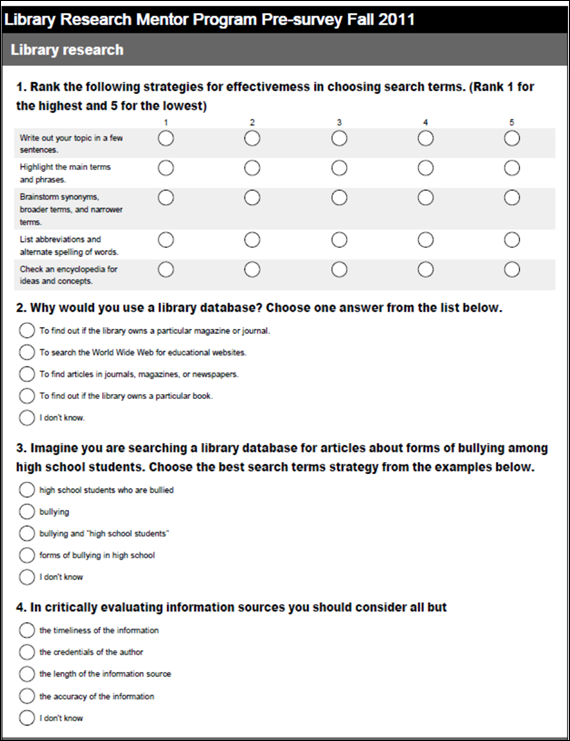

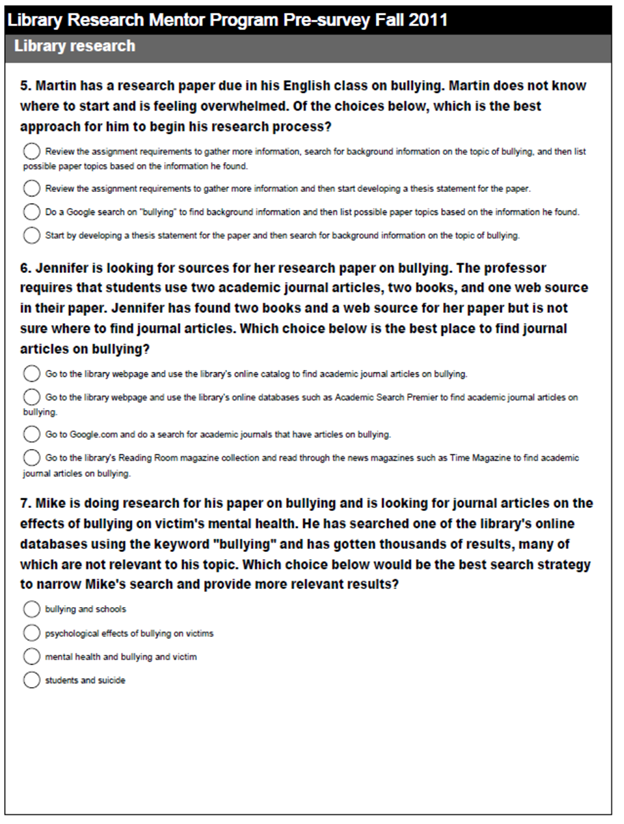

Several quantitative and qualitative measures were

designed to assess the goals identified for this study. A pre-test/post-test

instrument (Appendix A) measured students' knowledge about the library research

process by asking students to respond to questions, both fixed-choice and

open-ended, thereby demonstrating competency levels for defining,

investigating, and evaluating an information need.

The pre-test instruments were administered on the

first day of the course during the pilot semester, but in subsequent semesters

pre-tests were given during the second week of classes. This brief delay was

designed to allow students time to understand course expectations before making

a decision about participating in the study. Results of the pre-test formed a

baseline measure of students' abilities and were available to the librarian

prior to the first information literacy instruction session. Then, in the

penultimate class, the post-test instruments were administered. Assessment

instruments were administered online using SurveyMonkey™ software in one of the College's computer classrooms during

normal class hours.

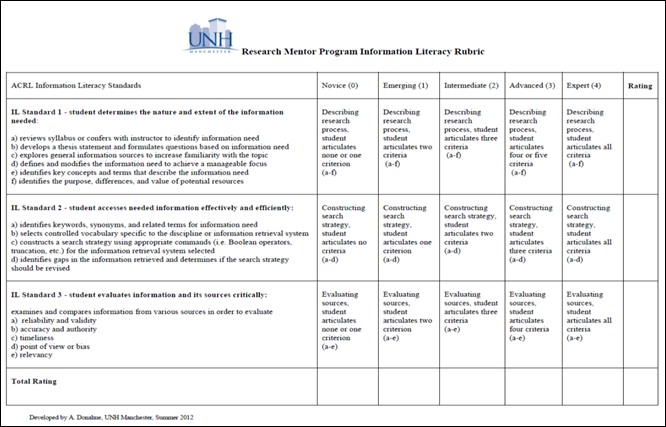

A rubric (Appendix B) was used to measure the

open-ended questions, but with limited experience in designing and using

rubrics a review of the literature was a necessary first step (Brown, 2008;

Crowe, 2010; Daniels, 2010; Diller & Phelps, 2008; Fagerheim

& Shrode, 2009; Gardner & Acosta, 2010;

Knight, 2006; Oakleaf, 2008, 2009a, 2009b; Oakleaf, Millet & Kraus, 2011). In the rubric design,

aligning the criteria to the objectives of the first-year information literacy

curriculum provided the framework within which to craft the measures. A

valuable source for examples of designing and using rubrics was found at the

RAILS (Rubric Assessment of Information Literacy Skills) website (http://railsontrack.info/).

Results

The sample size was small for each semester but

consistent with enrolment patterns for the College. During the pilot semester

(Spring 2011), 54 students enrolled in the First-Year Writing course but only

31 students agreed to participate in the study. The 57% participation rate was

disappointing and attributed to asking students to participate by completing

the pre-test on the first day of class before students had any understanding of

the class expectations. In each subsequent semester, the invitation to

participate and the administration of the pre-test occurred during the second

week of class resulting in a 100% participation rate each semester. In Fall 2011, the sample size was 76 students and in Spring

2012, the sample size was 48 students. Attrition rates for First-Year Writing

significantly affected the post-test sample size in every semester. In Spring 2011, only 28 students remained in the study. In Fall 2011, the post-test was completed by 55 students and in

Spring 2012, the post-test sample size numbered 32.

The pre-test/post-test instrument included six

questions designed to identify students' previous library research experiences

and an additional nine questions focused on three ACRL Information Literacy

Competency Standards: 1) The information literate student identifies a variety

of types and formats of potential sources of information; 2) The information

literate student constructs and implements effectively-designed search

strategies; and 3) The information literate student articulates and applies

initial criteria for evaluating both the

information and its sources (ACRL, 2000).

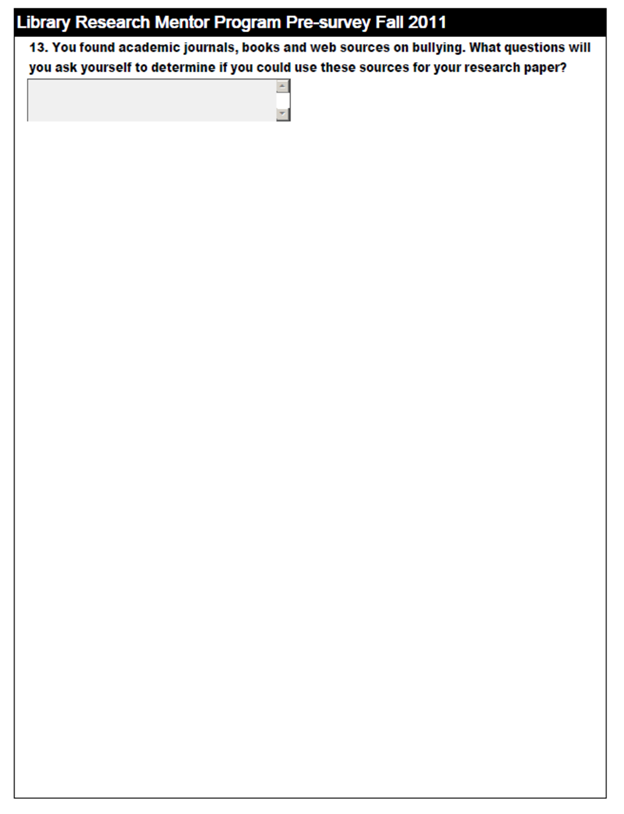

Among the nine information literacy questions were three

clusters of three questions that directly mapped these standards as learning

objectives assigned to the information literacy instruction sessions delivered

in the First-Year Writing course. Using a cluster approach enabled students to

demonstrate knowledge of each learning objective by answering a set of three

questions that explored a single information literacy competency from multiple

perspectives. Each cluster included two fixed-choice questions and one

open-ended question. A fixed-choice question was written as an informational

inquiry while the second was placed within the context of a potential research

scenario. The open-ended question required students to describe the research

activities they would complete to accomplish the task presented in the

question. The results of these cluster questions are discussed here.

Table 1 shows the results for the two fixed-choice

questions in each cluster. Findings indicated improvement each semester in five

out of six questions. The question that indicated a lack of improvement was the

question that measured the ability to evaluate sources in the research scenario

format. In post-test results for this question, students in Spring

2011 scored an 11% increase over pre-test results, but Fall 2011 students

scored a 7% decrease from their pre-test results. In Spring

2012, this question yielded no change in students’ pre-test to post-test

results.

Results for the remaining five questions point toward

an increase in knowledge over the baseline measure; the percent of change

across the remaining cluster questions ranged from a 6% to 57% increase. Table

1 visually depicts the quantitative results for each semester for both the

informational inquiry and the scenario based formats.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the results of the final

question in each cluster set; an open-ended question requiring students to

demonstrate the research skills they would employ in response to the task

described. Once again, each cluster question mapped to one of the information

literacy competency standards identified above.

Table 1

Results of the Fixed-choice Questions

|

Cluster Sets: IL Standards

1-3 |

Pre- test Spring 2011 |

Post-test Spring 2011 |

Pre-test Fall 2011 |

Post-test Fall 2011 |

Pre-test Spring 2012 |

Post-test Spring 2012 |

|

Library

Resources – info inquiry |

68% |

86% |

48% |

82% |

62% |

81% |

|

Library

Resources – scenario based |

74% |

100% |

61% |

82% |

75% |

81% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search

Strategies – info inquiry |

32% |

89% |

43% |

84% |

53% |

90% |

|

Search

Strategies – scenario based |

16% |

68% |

28% |

47% |

28% |

44% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source

Evaluation – info inquiry |

55% |

79% |

76% |

82% |

64% |

84% |

|

Source

Evaluation – scenario based |

74% |

85% |

80% |

73% |

78% |

78% |

Table 2

Information Literacy

Standard One – Determine the Nature and Extent of Information Needed

|

Ratings |

Pre-test Spring

2011 |

Post-test

Spring 2011 |

Pre-test Fall 2011 |

Post-test Fall

2011 |

Pre-test

Spring 2012 |

Post-test

Spring 2012 |

|

Novice |

71% |

57% |

38% |

22% |

30% |

31% |

|

Emerging |

23% |

36% |

43% |

27% |

35% |

50% |

|

Intermediate |

6% |

7% |

14% |

36% |

28% |

16% |

|

Advanced |

n/a |

n/a |

5% |

15% |

7% |

3% |

|

Expert |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

A rubric was developed to translate qualitative

responses into quantitative scores. The rubric scored students’ results on a

five-point scale from novice to expert, based on the number of criteria students

identified for each competency.

The first cluster set measured students’ ability to

define their information need. The seven criteria identified in ACRL’s

Information Literacy Standard One (ACRL, 2000) were incorporated into the

rubric used to score students’ responses. The rubric allowed for five rating

levels determined by the number of criteria students listed in their responses.

The rankings of novice to expert were based on students’ naming the criteria

associated with the standard. When students described their research process by

articulating one or no criteria they ranked at the novice level, two criteria

ranked at the emerging level, three criteria ranked at the intermediate level,

four or five criteria ranked at the advanced level, and six or more criteria

ranked at the expert level.

Table 2 shows the rankings for Information Literacy

Standard One. Results indicated students’ skill levels improved across most

semesters, as noted by a drop in novice rankings and a rise in emerging or

intermediate rankings. Among the seven criteria measured, students demonstrated

notable growth in three areas: 1) explores

general information sources to increase familiarity with the topic, 2) identifies key concepts and terms that

describe the information need, and 3) defines

and modifies the information need to achieve a manageable focus.

The second cluster set measured students' ability to

construct an effective search strategy. Four criteria identified in ACRL’s

Information Literacy Standard Two (ACRL, 2000) were incorporated into the

rubric used to score students’ responses. Although students in each semester

scored well in the pre-test on one criterion, identified keywords, synonyms, and related terms for information need,

approximately one-third of students' responses denoted no search strategy at

all. Post-test scores demonstrated that "no search strategy"

responses were reduced by 50% and that search strategies using a combination of

keywords with Boolean operators increased significantly; by 33% in Spring 2011,

47% in Fall 2011, and 19% in Spring 2012.

Table 3 demonstrates the change in rankings across the

three semesters. When students described their search strategy, if they merely

repeated the topic phrase or gave no answer they ranked at the novice level; if

they identified keywords and related terms they ranked at the emerging level;

and if they identified keywords and used Boolean operators they ranked at the

intermediate level. Although no students incorporated all four criteria denoted

for this information literacy standard, results demonstrated improvement as

novice rankings decreased and intermediate rankings increased.

The third cluster set asked students to name the

criteria they used to evaluate sources. Five criteria identified in ACRL’s

Information Literacy Standard Three (ACRL, 2000) were incorporated into the

rubric used to score students’ responses. When students described the criteria

used to evaluate sources, a response with one or no criteria was ranked at the

novice level, two criteria ranked at the emerging level, three criteria ranked

at the intermediate level, four criteria ranked at the advanced level, and five

criteria ranked at the expert level.

Table 4 shows the rankings for Information Literacy

Standard Three. In both Spring 2011 and Fall 2011 semesters, rankings indicated

that students increased skill levels, however, Spring 2012 results reflected no

improvement for this competency. Across all semesters in pre-test results, most

students identified a single criterion as sufficient to evaluate a resource.

The top three criteria noted were: 1) accuracy

and authority, 2) timeliness, and

3) relevancy. Post-test scores for

these three criteria remained strong in each semester, but the notable change

was that students regularly identified more than one criterion for evaluating

sources in the post-test data.

Table 3

Information Literacy Standard Two – Access Needed

Information Effectively and Efficiently

|

Ratings |

Pre-test

Spring 2011 |

Post-test

Spring 2011 |

Pre-test Fall 2011 |

Post-test Fall

2011 |

Pre-test Spring

2012 |

Post-test

Spring 2012 |

|

Novice |

32% |

14% |

27% |

11% |

14% |

12% |

|

Emerging |

68% |

54% |

57% |

27% |

72% |

50% |

|

Intermediate |

0 |

32% |

16% |

62% |

14% |

38% |

|

Advanced |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Expert |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Table 4

Information Literacy Standard 3 – Evaluate Information

and its Sources Critically

|

Ratings |

Pre-test

Spring 2011 |

Post-test

Spring 2011 |

Pre-test Fall 2011 |

Post-test Fall

2011 |

Pre-test

Spring 2012 |

Post-test

Spring 2012 |

|

Novice |

65% |

39% |

39% |

27% |

33% |

34% |

|

Emerging |

32% |

39% |

32% |

40% |

35% |

34% |

|

Intermediate |

0 |

22% |

26% |

27% |

32% |

32% |

|

Advanced |

3% |

0 |

3% |

6% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Expert |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Discussion

The data collected

in this phase of the evaluation study indicated a positive progression in

student learning. Students demonstrated growth of information literacy skills

throughout the semester. However, there are several limitations in this study

that make generalization of the findings impractical. The overall sample size

was small and the use of convenience sampling, rather than random sampling, may

not capture a true representation of first-year students' abilities. High

attrition rates in First-Year Writing courses led to lower post-test responses

which can impact accurate analysis of pre-test/post-test comparison data

leading to a potentially false conclusion.

The fixed-choice

test methodology incorporates further potential limitations. The questions

measure students' knowledge of facts, but tend to “measure recognition rather

than recall” (Oakleaf, 2008, p. 236) which is an

indirect assessment of students’ knowledge but not necessarily a measure of

students’ ability to apply that knowledge appropriately. On the positive side,

this methodology is easily administered and analyzed; it is locally-specific

and allows for timely measurement of the objectives from each information

literacy instruction session. With the data collected in this study, the

librarian can adapt lesson plans and activities to respond to students'

developmental readiness level more fully.

The open-ended

questions gave students the opportunity to articulate their research behaviour, enabling a more direct measurement of their

ability to apply information literacy skills. A rubric was an effective scoring

mechanism to convert the qualitative responses to a quantitative measure that

could be analyzed against the results of the other two cluster set questions.

Although the rubric made scoring results possible, the process was considerably

more time-consuming than anticipated. This methodology also contributed to

potential limitations in the study due to the use of a single rater to score

results. Although effort was employed to maintain an objective scoring plan, it

was challenging to interpret students' responses consistently when scoring at

"different points in time" (Oakleaf, 2009b,

p. 970). Use of trained student raters has been an efficient and effective

approach at other institutions and may be appropriate in future rubric scoring

to increase reliability of the results (Knight, 2006).

This 18-month

study was undertaken beginning in Spring 2011 and the

results of this study were presented at the Library Assessment Conference in

October 2012. The positive results of this study encouraged the UNH Manchester

librarians to expand the reach of the Research Mentor Program beyond the

First-Year Writing courses. The credit-bearing Tutor Development course was

revised to include training in subject-specific databases. This study used the

ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards as criteria for evaluating

students’ information seeking skills. In February 2015, the ACRL Board affirmed

the Framework for Information Literacy

for Higher Education. As librarians incorporate the six concepts of the Framework into the information literacy

curriculum, a further study of this peer-to-peer learning approach would be a

valuable addition to the Research Mentor Program evaluation.

Conclusion

This paper

examined the findings from a selected section of the pre-test/post-test

instrument used to measure change in student learning in our First-Year Writing

course. Through this study, an historical snapshot of the effectiveness of

employing a peer-to-peer learning approach with first-year students emerged.

The primary assessment instrument incorporated three cluster sets of

fixed-choice and open-ended questions mapped to the curriculum objectives for

information literacy instruction, and the findings demonstrated a positive

progression toward increased learning in the three targeted areas identified:

1) using library resources correctly, 2) building effective search strategies,

and 3) evaluating sources appropriately. Students scored higher in the

fixed-choice questions than the open-ended ones, demonstrating the ability to

more effectively identify the applicable information literacy skill than use

the language of information literacy to describe their own research behavior.

The findings, although specific to the College’s local situation and not

generalizable, are a valuable baseline for informing teaching and learning

practice.

The method used was

a low-key, locally-developed instrument that provided timely data to measure

students understanding of concepts taught and to apply those concepts

correctly. This instrument provided an indirect assessment of students’

learning by relying on their ability to recognize the correct response from a

selection of possible options. This approach is easily administered and

analyzed but results demonstrated that students were better able to recognize

components of the research process when given choices than articulate the steps

they would undertake when conducting research. Further assessment that directly

measured student performance would strengthen the conclusions attained in this

study. Although the conclusions are not generalizable to other institutions, the

findings were a valuable component of an ongoing program evaluation.

References

Artz, J. (2005). Libraries and learning center

collaborations: Within and outside the walls. In J. K. Elmborg

& S. Hook (eds.), Centers for

learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration (pp.93-115).

Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries.

Association of College & Research

Libraries. (2000). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher

Education. Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries.

Bodemer, B. B. (2013, Apr.). They not only can

but they should: Why undergraduates should provide basic IL instruction. Paper

presented at the Association of College and Research Libraries annual

conference, Indianapolis, IL, USA.

Boff, C., & Toth,

B. (2005). Better-connected student learning: Research and writing project

clinics at Bowling Green State University. In J.K. Elmborg

& S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for

learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration (pp. 148-157).

Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries.

Brown, C. A. (2008). Building rubrics: A

step-by-step process. Library Media

Connection, 26(4), 16-18.

Cannon, K., & Jarson,

J. (2009). Information literacy and writing tutor training at a liberal arts college.

Communications in Information Literacy, 3(1),

45-55. Retrieved from http://www.comminfolit.org/index.php?journal=cil

Cooke, R., & Bledsoe, C. (2008).

Writing centers and libraries: One-stop shopping for better term papers. The Reference Librarian, 49 (2),

119-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763870802101310

Crowe, K. (2010, Oct.). Assessment =

improved teaching and learning: Using rubrics to measure information literacy

skills. Paper presented at the 2010 Library Assessment Conference in Baltimore,

MD, USA. Retrieved from: http://libraryassessment.org/archive/2010.shtml#2010_Schedule

Currie, L., & Eodice,

M. (2005). Roots entwined: Growing a sustainable collaboration. In J.K. Elmborg & S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration

(pp. 42-60). Chicago, IL.: Association of College

& Research Libraries.

Daniels, E. (2010). Using a targeted

rubric to deepen direct assessment of college students' abilities to evaluate

the credibility of sources. College &

Undergraduate Libraries, 17(1), 31-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10691310903584767

Deese-Roberts, S., & Keating, K. (2000).

Integrating a library strategies peer tutoring program. Research Strategies, 17(2/3), 223-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0734-3310(00)00039-2

Phelps, S. F. (2008). Learning outcomes,

portfolios, and rubrics, oh my! Authentic assessment of an information literacy

program. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(1),

75-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2008.0000

Elmborg, J. K. (2005). Libraries and writing

centers in collaboration: A basis in theory. In J.K. Elmborg

& S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for

learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration (pp. 1-20).

Chicago, IL.: Association of College & Research

Libraries.

Fagerheim, B. A., & Shrode,

F. G. (2009). Information literacy rubrics within the disciplines. Communications in Information Literacy, 3(2),

158-170. Retrieved from http://www.comminfolit.org/index.php?journal=cil

Fensom, G., McCarthy, R., Rundquist,

K., Sherman, D., & White, C. B. (2006). Navigating research waters: The

research mentor program at the University of New Hampshire at Manchester. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 13(2),

49-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J106v13n02_05

Foutch, L. J. (2010). Joining forces to

enlighten the research process: A librarian and writing studio integrate. College & Research Libraries News, 71

(7), 370-373.Retrieved from: http://crln.acrl.org/

Furlong, K., & Crawford, A. B. (1999).

Marketing your services through your students. Computers in Libraries, 19 (8), 22-26.

Gardner, S., & Acosta, E. S. (2010,

Oct.). Using a rubric to assess Freshman English library instruction. Paper

presented at the 2010 Library Assessment Conference in Baltimore, MD, USA.

Retrieved from: http://libraryassessment.org/archive/2010.shtml#2010_Schedule

Giglio, M. R. & Strickland, C. F. (2005).

The Wesley College library and writing center: A case study in collaboration.

In J. K. Elmborg & S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for learning: Writing centers and

libraries in collaboration (pp. 138–147). Chicago, IL.:

Association of College & Research Libraries.

Gruber, A. M., Knefel,

M. A., & Waelchli, P. (2008). Modeling scholarly

inquiry: One article at a time. College

& Undergraduate Libraries, 15 (1-2), 99- 125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10691310802177085

Holliday, W. & Nordgren,

C. (2005, April). Extending the reach of

librarians: Library peer mentor program at Utah State University. College & Research Libraries News, 66(4),

282-284. Retrieved from: http://crln.acrl.org/

Knight, L. A. (2006). Using rubrics to

assess information literacy. Reference

Services Review, 34(1), 43-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320610640752

Leadley, S., & Rosenberg, B. R. (2005).

Yours, mine, and ours: Collaboration among faculty, library, and writing

center. In J. K. Elmborg & S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for learning: Writing centers and

libraries in collaboration (pp. 61-77). Chicago: Association of College

& Research Libraries.

Lowe, M., & Lea, B. (2004). When

worlds collide: Libraries & writing centers. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 8(1), 134-138. Retrieved from: http://rapidintellect.com/AEQweb/

Millet, M. S., & Chamberlain, C.

(2007). Word-of-mouth marketing using peer tutors. The Serials Librarian, 53(3), 95-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J123v53n03_07

Nelson, R. R. (1995/96). Peer tutors at

the collegiate level: Maneuvering within the zone of proximal development. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 27(1),

43-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10790195.1996.10850030

Oakleaf, M. (2008). Dangers and opportunities: A

conceptual map of information literacy assessment approaches. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(3),

233-253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0011

Oakleaf, M. (2009a). The information literacy

instruction assessment cycle: A guide for increasing student learning and

improving librarian instructional skills. Journal

of Documentation, 65(4), 539-560. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220410910970249

Oakleaf, M. (2009b). Using rubrics to assess

information literacy: An examination of methodology and inter-rater

reliability. Journal of the American

Society for Information Science & Technology, 60(5), 969-983. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.21030

Oakleaf, M., Millet, M. S., & Kraus, L. (2011).

All together now: Getting faculty, administrators, and staff engaged in

information literacy assessment. portal: Libraries and

the Academy, 11(3), 831-852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2011.0035

White, C. B., & Pobywajlo,

M. (2005). A library, learning center, and classroom collaboration: A case

study. In J.K. Elmborg

& S. Hook (Eds.), Centers for

learning: Writing centers and libraries in collaboration (pp. 175-203).

Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries.

Appendix A

Questionnaire

Appendix B

Information Literacy Rubric